Workers’ Inquiry and Global Class Struggle: A Conversation with Robert Ovetz and Jenny Chan

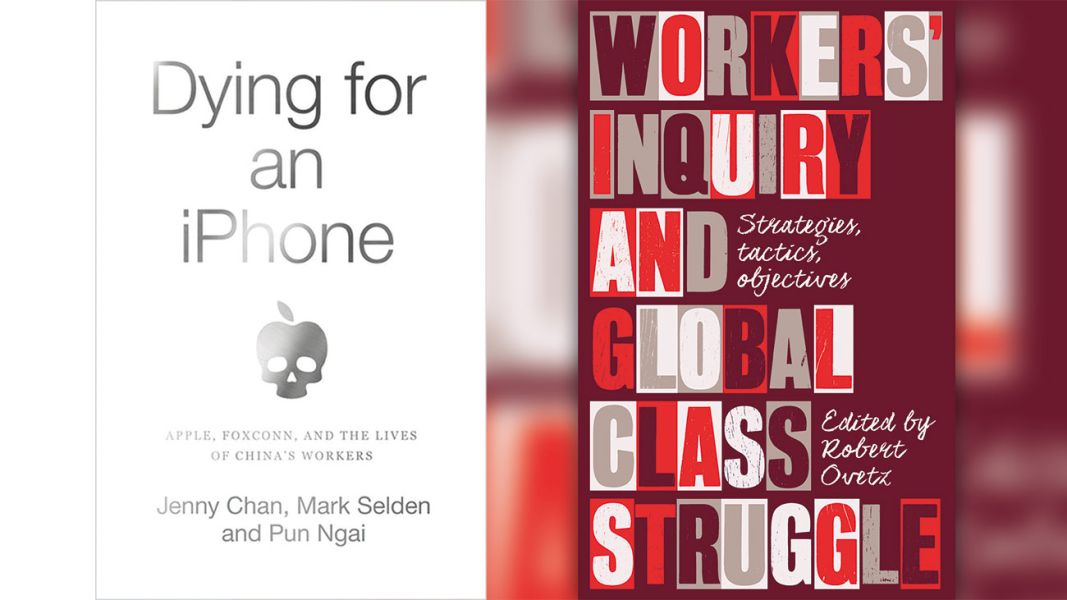

As the Made in China Journal was born as a platform to document labour struggles in China, we always welcome the publication of books and studies that offer novel perspectives on the ‘world of labour’. In this conversation, we discuss two recent additions to the literature: Workers’ Inquiry and Global Class Struggle: Strategies, Tactics, Objectives, edited by Robert Ovetz (Pluto Press, 2020), and Dying for an iPhone: Apple, Foxconn, and the Lives of China’s Workers, authored by Jenny Chan, Mark Selden, and Pun Ngai (Haymarket Books and Pluto Press, 2020; translated into Korean by Narumbooks, 2021). In the former, Ovetz collects case studies from more than a dozen contributors, looking at workers’ movements in China, Mexico, the United States, South Africa, Turkey, Argentina, Italy, India, and the United Kingdom. The latter is a book-long inquiry into labour conditions in the plants in mainland China of the Taiwanese-owned company Foxconn, an electronic components supplier for Apple and other global firms.

Ivan Franceschini: Robert, many intellectuals have bemoaned that the working classes under neoliberalism have been discursively erased from history, becoming shadows or, perhaps more aptly, ghosts of their former selves. In the opening of your collection of essays, you acknowledge that capitalism has been in crisis during the entire period of neoliberalism, and you pose the question: ‘Is it merely a crisis of its own making or does the working class have a role to play in it?’ What is your answer to this question and what does it tell us about the current state of the working class?

Robert Ovetz: My mentor and friend Harry Cleaver taught me to read through capital to see class struggle by engaging in what he calls ‘an inversion of class perspective’. We can see class struggle by studying the current actions, organisation, and strategies of capital—what is called the ‘technical composition’ of capital. The evidence is there, but we have to learn how to find it, read it, and apply it for the purpose of class struggle. That is the role of a workers’ inquiry into the current class composition of both capital and the working class.

In the past few months, there has been a significant uptick in the number of strikes and credible strike threats in the United States. With all the attention towards this current crest in the wave of class struggle, we tend to zoom out to look at other collective and individualised indicators of class conflict besides strikes. One thing that has been overlooked is the number of strike threats that proved credible enough to settle before the strike occurred. During the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, we have also seen a large number of workers leaving their jobs to move to higher-paying and safer jobs. Workers are constantly on the move from one job to another, and across borders from one country to another, carrying with them their experience of class struggle. Worker mobility is another form of struggle, albeit a highly individualised one.

For decades, the United States and other industrialised countries have struggled with the supposed problem of low growth and declining rates of return on capital investment despite rates of productivity rising. This indicates that despite workers getting pounded by stagnant wages, worsening working conditions, digital speed-ups, increasing precarity, etc., capital has remained insecure itself about putting workers to work. We can see this with the widespread introduction of artificial intelligence and other algorithmic management techniques to control workers by augmenting, supplementing, and replacing us. Since the journal Zerowork was published in the 1970s, no-one has yet presented a convincing analysis of why capital continues to flee the reliance on work if workers are so weak and not engaged in struggle, whether overt or covert.

This apparent paradox should be the focus of our work as labour scholars, to understand where the vulnerability and choke points are, and devise tactics and strategies to apply leverage there to tip the balance of power back in our favour. To do that, we need to conduct a global workers’ inquiry into the current class composition of both capital and the working class in as many countries and sectors as possible to inform the struggle.

IF: Can you elaborate a bit more about this ‘workers’ inquiry’ approach? What does it entail and what advantages does it present?

RO: Elements of a workers’ inquiry approach to understand the current class composition run through each chapter of my book. While none is complete, they all contribute the first or second steps of what is needed to continue building a global inquiry into the current class composition of what is called the technical composition of capital, the current composition of the working class, and how working-class power is or can be recomposed. Let me briefly explain what each means.

First, capital’s current organisation of production is a response to the last cycle of class struggle. Capital seeks to restore control by reorganising work, introducing new technology, devising management methods, fragmenting workers by job status, altering the global supply chain, and creating hierarchies of wages, race, gender, legal status, etc. In the process of implementing a new technical composition of capital, the working class is decomposed, and its power fragmented and defeated. Capital wins this round.

To recompose our power, to win on the new terrain of struggle, it is first necessary for workers to understand both capital’s new current technical composition and how work and workers are organised. It becomes necessary to examine and understand changes in work, the characteristics of workers, the roles of technology to control and manage work, how different workplaces are connected in the supply chain, the connections between the waged and unwaged workplaces and the workplace and community, and the demographics of who the workers are. By doing this, we uncover what I call the ‘invisible committees’ of workers coordinating and struggling together in order to devise new tactics, strategies, and forms of organisation that can expand and circulate these struggles in order to restore the balance of power to the workers (Ovetz 2019). By doing this we identify the weak linkages, or what Jake Wilson and Manny Ness call choke points, in the technical composition where workers can apply the greatest pressure to cause disruption and extract gains (Alimahomed-Wilson and Ness 2018). Workers’ inquiry is the method of understanding these changes, or the current class composition, and applying them to organising and struggle.

IF: Throughout your introduction, you draw from the pioneering work of Italian operaisti such as Raniero Panzieri and Romano Alquati. What lessons can we draw from the Italian workerist experience when it comes to understanding the challenges facing the working class today? And what part of their approach did not stand up to the test of time?

RO: The greatest lesson we can learn from the Italians is that the waged workplace is still our greatest source of power. In order to wield that power, we need to understand capital’s strategy, its technical composition, and use that information to self-organise and recompose our class power. Panzieri, Alquati, Quaderni Rossi, Socialisme ou Barbarie, Zerowork, and Midnight Notes—all left us with an invaluable methodology for self-organisation, identifying capital’s strategy and weakness, and how to exploit it. The problem is that it is incredibly challenging to inject a focus on organising for power in the workplace, even when we have a union. Our unions have been eroded of their power as a result of decades of labour legislation, the reorientation to advocacy, mobilising, lobbying, suppressing class struggle in favour of liberal identity politics, and being harnessed to liberal, labour, and social-democratic parties. Forty years of this has resulted in organising no longer being taught, practised, or even emphasised. Our unions have been taken over by leadership that transform them into adjuncts to political parties and strangles efforts to organise the disruptive power we still have over work, which is the only way we can make system change—by disrupting the capitalist relations of production. And then, even when we do organise, the objective is merely to get a small wage increase, protect benefits, and preserve the contract. We almost never put the struggle over and against work at the centre. To struggle against work would be to struggle against the entire capitalist economy, which is a critically vital strategy if we are to transcend capitalism and keep it from roasting the planet.

While we can learn much from those who transformed Marx’s workers’ inquiry into a practice of learning from struggle, they limited their inquiries to single workplaces. I try to remember that class struggle is always changing, shifting, and transforming. I think of it as a spiral dance in which one wave of victories is countered by capital and, if it is defeated, we move the struggle to a higher, more intense level and the cycle begins again. However, it need not be an endless spiral. If humanity and the rest of our ecosystem are to survive, we need to rupture this dialectic, as Cleaver (2017) puts it. Those who have used workers’ inquiry in the past were too limited in their focus on single workplaces and countries. We need the continual project of global workers’ inquiries that Ed Emery called for in 1995, in which we are constantly feeding stories and lessons from workers’ inquiries from around the world as we circulate our struggles.

IF: Your book offers inquiries from nine countries on four continents. How did you choose these case studies?

RO: I took up Emery’s (1995) call in the journal Common Sense for a global workers’ inquiry. As capital cooperates, plans, and strategises globally, so must the working class. From the first enclosures of the Americas, capital has always been global. It has had to be. As workers’ struggles knock capital off balance, it seeks both a spatial and a technical solution, as Beverly Silver (2013) put it. The spatial solution has been there from the beginning, fleeing the struggles of the sixteenth century in Europe. Except for the short experiments with the four workers’ Internationals, the anti-imperialism movements, the post–World War I council movement, 1968, and the Arab Spring and Occupy, class struggle has also been global but lacking the concerted coordinated cooperation that will take us to the next terrain of struggle. We are seeing many impressive efforts to do exactly that with the two internationals of Amazon Workers International and the International Alliance of App-Based Transport Workers, which are unions coordinating their struggles globally with powerful impact. Where localised trade unions have tried and failed or moved the struggle into the electoral arena or courts, these self-organised workers have demonstrated just how vulnerable these global behemoths really are.

In response to Emery’s call, I decided to ask those working with or interested in workers’ inquiry into class composition to carry out one inside their country so we could begin the conversation. What came out was an impressive first baby step towards the beginning of doing a global workers’ inquiry. Together, the series of earlier articles I curated for the Journal of Labor and Society and the book chapters showed us what is possible as well as how much more work is needed. There is some good work being done by Notes From Below, Into the Black Box in Italy, and a few others around Europe and Brazil, but the network we started has gone dormant and the coordination is stalled. It is a gigantic undertaking, but I have high expectations. Because it is urgently needed, the work will continue.

IF: Among the essays included in the book is a reflection by Jenny Chan on the challenges and opportunities related to labour organising in China. Jenny is also the co-author, along with Mark Selden and Pun Ngai, of Dying for an iPhone. Jenny, you have been researching labour conditions in China for more than a decade; can you elaborate on the challenges you faced in conducting this type of workers’ inquiry in the Chinese context?

Jenny Chan: The challenges come from our contestations for economic resources and sociopolitical power, and the forces that are combating us. Dying for an iPhone is an in-depth inquiry into the vulnerability of contemporary supply-chain structures and an assessment of the potential power of workers at the key nodes of global electronics production. Workers’ struggle reveals the depth of control and institutional impasse under the state–capital nexus.

Fundamentally, the ruling Chinese Party-State has guarded against organised opposition by workers through the law, the court, and the police. Foxconn workers have sought to reclaim their union at the workplace level but the Foxconn union—not unlike many other enterprise unions—remains in the tight grip of senior management. Moreover, the official All-China Federation of Trade Unions has monopolised the institution of worker representation across all levels. The battles for labour rights by protesting workers and supporting researchers are therefore very difficult.

IF: In the late 2000s and early 2010s, and particularly after the spate of suicides among its employees in 2010, Foxconn became a symbol of labour exploitation in China. One decade later, does the company still deserve this reputation or has there been any improvement in labour conditions?

JC: Foxconn earns its name by essentially turning humans into machines in the ‘scientific’ labour process. Yet human workers need to find meaning in life. During the first five months of 2010, when more than a dozen young workers ended their lives, one after the other, the corporate executives admitted that they were ‘caught by surprise’. Their awakening, in our analysis, is an illusion. The pay raise, for example, was partially offset by the removal of bonuses and subsidies in a fiercely competitive market. To lower costs and enhance flexibility, Foxconn and other companies have further outsourced labour through so-called internship programs.

During the summer of 2010, Foxconn recruited as many as 150,000 ‘student interns’ to meet production deadlines and to ramp up production. The mobilisation of intern labour was a joint effort between Foxconn managers and local officials, who prioritised investment over worker protections. Beginning from April 2016, when the Beijing government was pressured to cap the deployment of student interns to 10 per cent of the company’s workforce, Foxconn moved to hide interns from inspection. In this way, the abuse of teenage students has become more hidden from public scrutiny. In a broader context, the Chinese state has classified interns as students, not employees, thus the systematic deprivation of their legitimate rights. Global tech behemoths have continued to benefit from the interning of students in their supply chains.

The super exploitation of low-wage ‘student workers’—who are obligated to work to earn their educational credentials—dampens the intended national effort of upskilling and industrial upgrading. When intern credits are required for obtaining a diploma, local governments can extract the labour of students, conscripting them into manufacturing employment to meet production quotas. The students eventually receive an educational credential, but such ‘internships’ actually have very little educational value. At a time of slowing economic growth, a shrinking pool of workers, and an ageing population, vocational school students and graduates could play a significant role in China’s economic and technological development if they are protected against violations of labour law, and particularly if they were to receive appropriate training leading to better jobs and the use of higher levels of technology.

IF: Over the past decade, Foxconn was also at the forefront of robotisation in China, with its leaders often boasting about their plans for replacing workers with machines. Has this replacement happened? And what does the case of Foxconn tell us about the changes that have been occurring in the labour field more broadly in China?

JC: Foxconn makes Foxbots in-house while importing robotic arms at home and abroad. Styled as the ‘harmonious men’ in the company’s lingo, Foxbots are automatons capable of spraying, welding, pressing, polishing, quality testing, and assembling printed circuit boards. In the accelerated process of automation, ‘less-competitive’ workers were already made redundant even when Foxconn has never disclosed the total number of adversely affected workers.

Foxconn is dominant in global electronics manufacturing and is branching out to other higher value-added industries and services in the face of strong competition. We have witnessed the concentration of capital and the development of oligopolistic globalisation in a rising China. Across state-owned, foreign-invested, and privately owned enterprises, the Chinese Party-State has vastly expanded its control to achieve national objectives. Officials are appointed to new oversight offices within large companies. The evolution of the state, capital, and labour relations in China’s digital economy requires long-term observation.

No-one is free when others are oppressed. Dying for an iPhone—sparked by the rash of suicides and grounded in undercover research on Foxconn, Apple, and the Chinese state—has attempted to inform and heighten social consciousness concerning labour issues to inspire transnational activism in opposition to the oppression of labour wherever it is found. Despite pressures from both the Chinese authoritarian state and global corporations, grassroots labour organising for sustainable change continues. Buyers’ interventions in their suppliers through such methods as audits of factory conditions and the introduction of new labour standards to prevent work-related suicides in corporate social responsibility programs have expanded over the past decade. Consumer awareness of the links between electronics manufacturing and the plight of workers has also grown. In Europe, for example, a number of universities and other public sector organisations have leveraged their procurement power to require brands and their suppliers to protect and strengthen workers’ rights in their contracts. Since a substantial part of Apple’s market is education-oriented and their claims to ethical practices directly influence the perceptions of students, faculty, and the public institutions which buy their products, this might intensify pressure on the company in the many countries that constitute its global market.