Concrete Sublime and Somatic Intensity

Visualising Water Engineering in Socialist China

As flood and drought have been the major threats to people’s livelihoods in agricultural societies, river management has generally been a core administrative responsibility of local and state authorities around the world and throughout history. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is no exception. In the 1950s, the Party-State was keen to boost agricultural productivity and demonstrate its capacity for labour mobilisation by transforming the country’s rivers and mountains. As part of the global revolution in concrete technology and the continuation of China’s long tradition of water management, the construction of large-scale water engineering infrastructure became an essential task of the fledgling socialist state in that decade. With the commencement of the Huai River campaign, the comprehensive planning of the Yellow River, and a suite of flood control and hydropower projects across the country, the waterscape of China underwent unprecedented transformation. What is often overlooked is how, in addition to the material achievements in terms of the organisation of water, the erection of tens of thousands of concrete, rock, and earthen dams, the waterscape transformation also rendered a revolution in art and visual culture.

According to Christine Ho (2020), during the Mao Zedong years before the Cultural Revolution—the so-called 17 Years (1949–66)—three genres of painting emerged as mainstream: industrial sublime, revolutionary history, and cultural diplomacy. The new state’s pursuit of industrialisation and modernisation rendered scenes of industrial construction one of the three major themes of artistic production at that time. Because of the scale and nature of water engineering projects, dams and reservoirs became a popular subject in visualising the industrial sublime of socialist China. Centred on the water engineering–themed illustrations and photographs created in the 1950s and 1960s, this essay seeks to examine the connections between those infrastructure projects, visual culture, and socialist politics. While the artworks followed and reflected the overt changes in the physical landscape, the creation and exhibition of those works also affected people in a more covert and subtle way. For many artists, regardless of whether their work was spontaneous or commissioned, the creation process was a chance to re-educate and adapt themselves to the Maoist revolutionary culture. For the audience, the works showcased the achievements of the socialist state in a visually artistic and spiritually uplifting manner. In so doing, this genre intended to inspire awe of the socialist state and make the audience adamant supporters of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

In 1942, Mao gave a series of talks during his meetings with literature and art workers in Yan’an. According to Mao, literature and art—the most important mediums of communication—should serve the masses and the Communist revolution (McDougall 1980). In 1954, Jiang Feng, the president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, published an article in the People’s Daily complaining about the indifference to politics and the cultural deficiency of some artists. A few months later, Zhu Dan, Jiang’s colleague at the academy, called for the improvement of the political calibre of artists. Quoting Maxim Gorky on the role of ‘writers as the eyes, ears and voices of social classes’, Zhu explicitly stated that the arts should be the weapon of social classes and ought to serve the Party and its revolutionary enterprise (Zhu 1955: 5). Wu Zuoren, then a professor at the academy and vice-president of the Chinese Artists’ Association, called for immediate action. In this context, while the visualisation of Communist revolutionary history continued to be the focus of art in state propaganda and politics, it was joined by the visualisation of agricultural and industrial production and infrastructure construction in marking the expansion of Chinese socialist visual culture.

Traditional Chinese painting (国画, guohua) had long been criticised for failing to reflect the social reality of China. In particular, the genre of landscape painting was exclusively associated with the aesthetic of the privileged literati class. Hence, it was marginalised in the first few years of the PRC. As a result, poverty, unemployment, and low morale prevailed in the guohua field (Gu 2020: 169). In 1953, Communist poet Ai Qing, then a member of the executive council of the Chinese Artists’ Association, gave a speech to a group of artists in Shanghai in which he called for the reform of Chinese painting, stating that ‘in painting landscapes one must paint real mountains and streams’ (Ai 1953). Painters were encouraged to innovate the content of their practice and their skills. At an institutional level, the establishment of the Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu Chinese painting institutes in 1957 and 1960 provided many ink artists with a reliable source of income and a platform to create and improve their artistic practice. Compared with wartime instability and economic struggles under the Nationalist Government, many artists appreciated the peace that followed the Communist victory and were excited about the progress and development being promised by the establishment of the PRC (Lu 1986). Nevertheless, as they became assimilated constituents of the Communist state’s cultural apparatus, artists affiliated with those institutes were expected to comply with the CCP’s propaganda objectives.

Controlling the Huai River

Even before the formation of these institutes, many artists had begun to explore a new style of portraying rivers and mountains. In 1950, the PRC’s first large-scale water engineering project was launched, in the Huai River Valley (Pietz 2015). Along with its technical and management apparatus, a fine arts team was organised, affiliated with the Political Department of the Huai River Campaign Commission, bringing employment for artists across the country.

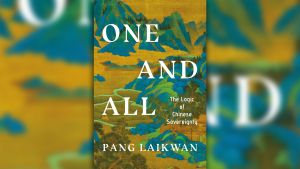

There were many water engineering infrastructure projects in the Huai River campaign, but among them the multi-arch Foziling Dam was one of the most technologically challenging. The dam was on the Pi River, a tributary of the Huai River in Anhui Province. It was purported to be the first large-scale hydropower project being built under the CCP’s watch. The spectacular concrete dam was a striking visual element for artistic production. For example, Zhang Xuefu’s ink painting Transform Flood into Benefit (化水灾为水利, see Figure 1) foregrounds the concrete dam. Human figures in the lower part of the painting and the remote mountains in the upper background emphasise the dam’s spectacular size. Because of its impressive visualisation of the technological sublimity of new China, the painting was gifted by the Chinese Government to Indonesian President Sukarno in 1956.

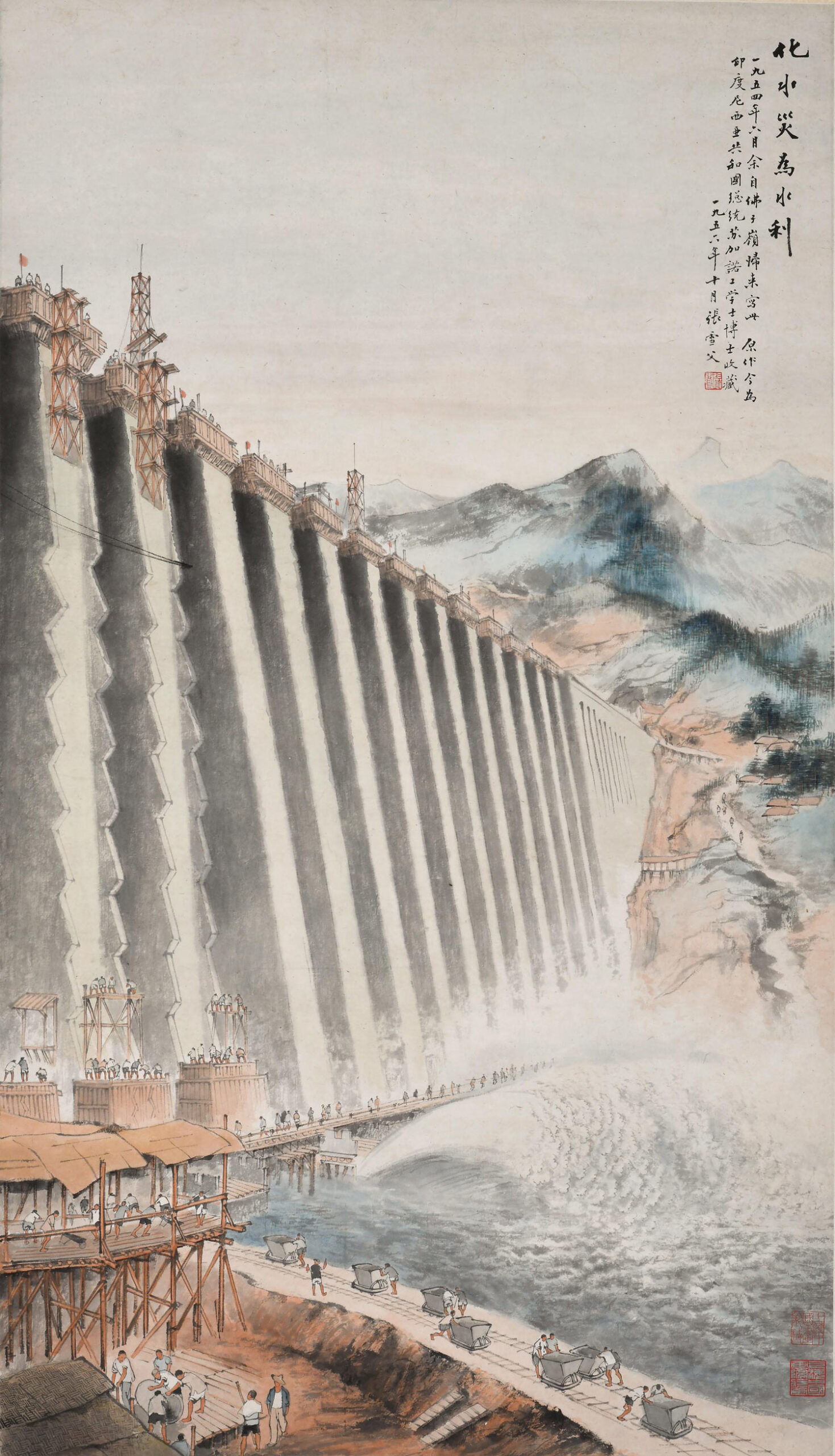

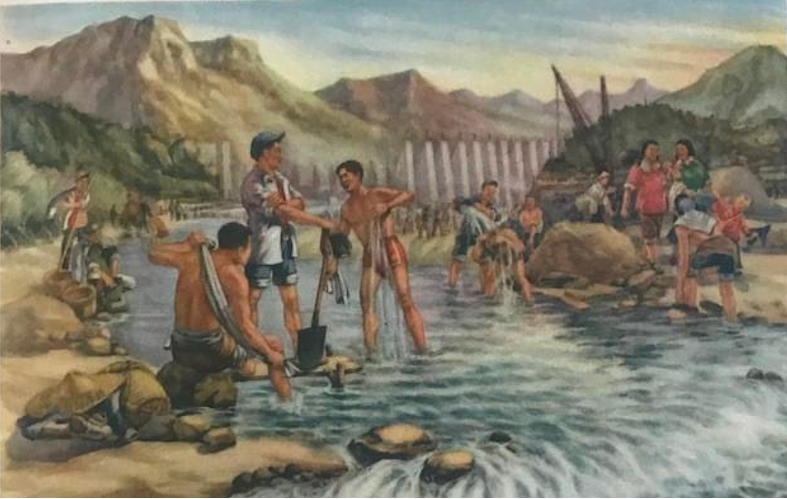

Other artists approached the infrastructure from different perspectives. For instance, Xiao Shufang’s gouache painting of Kids at the Foziling Reservoir Construction Site (佛子岭水库工地的儿童, see Figure 2) is refreshing. Unlike other works, which foreground the concrete dam, Xiao placed it in the distance as background behind several children playing a game of dam-building. The colour and composition of the watercolour convey a bright and joyful sentiment to viewers. He Qitao’s gouache painting After Work (劳动后的休息, see Figure 3) depicts dam workers relaxing and washing in a stream after a day’s hard work at the construction site. This type of ‘rest’ scene would be hard to find in artworks created during the Great Leap Forward (1958–62).

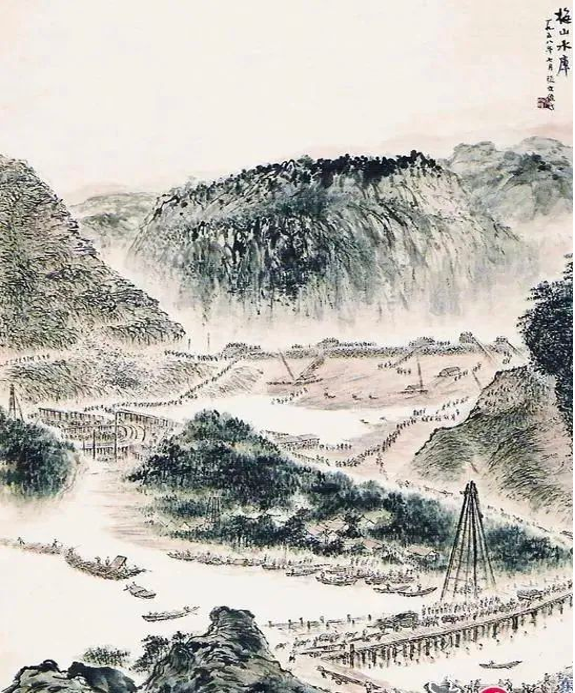

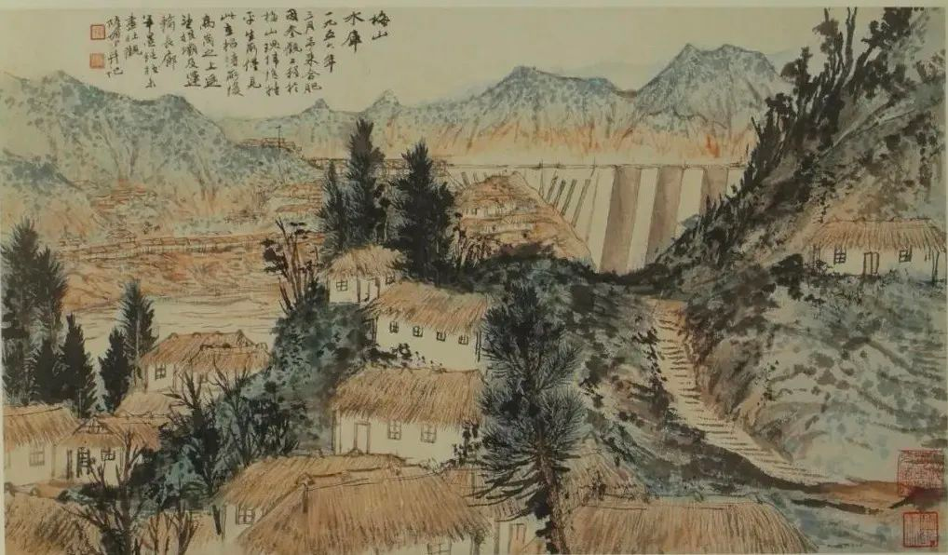

Meishan Reservoir, a project on the Shi River, another tributary of the Huai, also drew the attention of artists. In a famous painting (see Figure 4), guohua painter Zhang Wenjun depicted a magnificent bird’s-eye view of well-organised labour at the Meishan dam construction site—a notable divergence from the classical style, as scenes of human labour of that magnitude were generally not to be found in traditional Chinese landscape painting. Zhang was deeply impressed by what he saw during his visit to the construction site:

In none of the previous eras was it possible to organise so many people to labour voluntarily, intensely, and happily to build a wonderful life for the people. This thoroughly reflects the spirit of our new era. I think this is the best subject for modern Chinese landscape painters. (Zhang 1962: 30)

The combination of labour and landscape aligned well with the socialist state’s ideology. Hence, the painting was praised as representing the ‘birth’ of a new Chinese landscape painting.

In another painting of the Meishan Reservoir (see Figure 5), Lu Yanshao foregrounded locals’ shabby homes with the concrete dam only as background, the thatched roofs reflecting the poverty of residents. Among the commissioned artworks, this could be interpreted as an individual expression at odds with the objectives of official propaganda. Yet, from a different angle, the destitute condition complemented the modernity promised by the dam.

Sanmenxia Dam on the Yellow River

It is impossible to talk about hydropower infrastructure projects in the early PRC without discussion of the Sanmenxia Dam on the Yellow River, which was most famously depicted in Wu Zuoren’s oil paintings. As a National People’s Congress (NPC) representative, Wu attended the second meeting of the First NPC, in 1955, at which vice-premier Deng Zihui presented the Yellow River Plan. With great enthusiasm, Wu aspired to engage through illustration with the epic changes on the Yellow River. Wu Zuoren was born in Suzhou in 1908 and studied oil painting in Europe in the 1930s. After 1949, he was appointed as the first provost of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. In the 1950s, he also served as the vice-president of the Chinese Artists’ Association, the principal of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and a representative of the NPC.

Wu was one of the most prominent artists in twentieth-century China. In a speech delivered in 1951, as a member of China’s cultural delegation to India, he articulated what he thought was the task of Chinese artists:

In general, the basic characteristic of fine art in China is close collaboration with politics. [It] aims to encourage and educate the masses. Art workers strive to learn from life, study policies proactively so that [our works] can reflect life correctly and win the fondness of the masses. (Wu 1951)

In 1955, as a representative of the NPC, Wu visited Sanmenxia for the first time and completed many sketches onsite. After returning to Beijing, he created his first oil painting of Sanmenxia, titled Zhongliudizhu (中流砥柱, see Figure 6).

In the painting, the hydropower project is still in its early stages, with no concrete dam yet visible. It depicts, from afar, the precipitous terrain of the steep gorge and the unique rocky islets standing amid the torrent—the work of mother nature. Yet, closer inspection reveals humans working on the right bank and the islets. Although the composition of the painting is predominantly about capturing the natural beauty of Sanmenxia, the almost oblivious human figures and tents suggest that nature is under reconstruction, and a human-engineered landscape will permanently replace the natural one. In Wu’s own words: ‘In Mao Zedong times, all natural barriers will be subdued. The harmful Yellow River will be turned into a beneficial river to serve the socialist construction’ (Wu 1956). Four years later, in 1959, Wu returned to Sanmenxia at the height of the Great Leap Forward. The rocky islets had been replaced with cranes and the concrete dam was under construction. In addition to a bird’s-eye view of the dam construction site, Wu painted a smaller scene centred on two cranes, a truck, and the Great Leap Forward slogan painted on the dam: ‘Long Live the General Route’ (总路线万岁) (see Figure 7). Seeing these paintings as a series, Wu successfully conveyed the technological sublime of the Sanmenxia project and the perceived triumph of the socialist state over nature.

During the Great Leap Forward campaign, high targets were set for agricultural and industrial production. Likewise, in the field of cultural production, quotas were assigned to each work unit (Ho 2020: 156). As a result, many Chinese ink paintings were created depicting the Sanmenxia hydropower project. As the first mega concrete dam on the Yellow River and the only hydropower project receiving Soviet assistance in the First Five-Year-Plan, Sanmenxia became a national focus for state propaganda (Ding 2021). Many Chinese painters across the country were organised by their work units to visit the dam site. Li Xiongcai, a guohua artist from Guangdong, visited Sanmenxia in 1958 and created multiple sketches of the project. Compared with Wu Zuoren’s paintings, Li’s focused on the scenes of busy work at Sanmenxia—probably due to the timing of his visit. One depicts an explosion at the construction site (see Figure 8). Li decided to record the moment by illustrating flying fragments—a scene never before illustrated in Chinese painting.

Another iconic example of Sanmenxia art is He Haixia’s Conquering the Yellow River series from 1959, in which he illustrated the same construction site scene from different angles. Like Li’s works, He’s were realistic reflections of the project site. Many art critics, however, suggested there was a lack of conceptual experimentation and ‘poetic’ expression in these landscapes (Gu 2020: 182).

In late 1960, Fu Baoshi, the director of the Jiangsu Provincial Chinese Painting Institute, organised 13 of the institute’s artists to engage in a nine-province tour over three months. Sanmenxia was their second stop, resulting in multiple paintings and sketches. Fu Baoshi’s The Yellow River Runs Clear (黄河清, see Figure 9) and Qian Songyan’s The Great Yu Temple (大禹庙, see Figure 10) were widely seen as the most outstanding works. Unlike other artists, Fu did not include the dam per se in the painting. Though he was excited to see the sublimity of the project’s hectic working scenes and gigantic machines, he realised there would be no inscape if he chose to illustrate these subjects. Coincidentally, before their visit, the Sanmenxia reservoir had begun to retain water. With the loss of velocity, sediment started to deposit and thus the Yellow River turned clear. After days of pondering, Fu was inspired by the old Chinese proverb: ‘When the Yellow River runs clear, a saint will emerge’ (黄河清, 圣人出).

Fu wrote:

Under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and Chairman Mao, the Chinese people are the real saints. ‘Yellow’ and ‘clear’ are the exact opposite. The object of the Sanmenxia project is to change the Yellow River, transforming water disasters into benefits. Therefore, I decided to address the concept of ‘clear’ in my painting. (Fu 1962)

By depicting powerlines and a clear reservoir, Fu’s painting left space for viewers to imagine the revolutionary changes on the river beyond the frame.

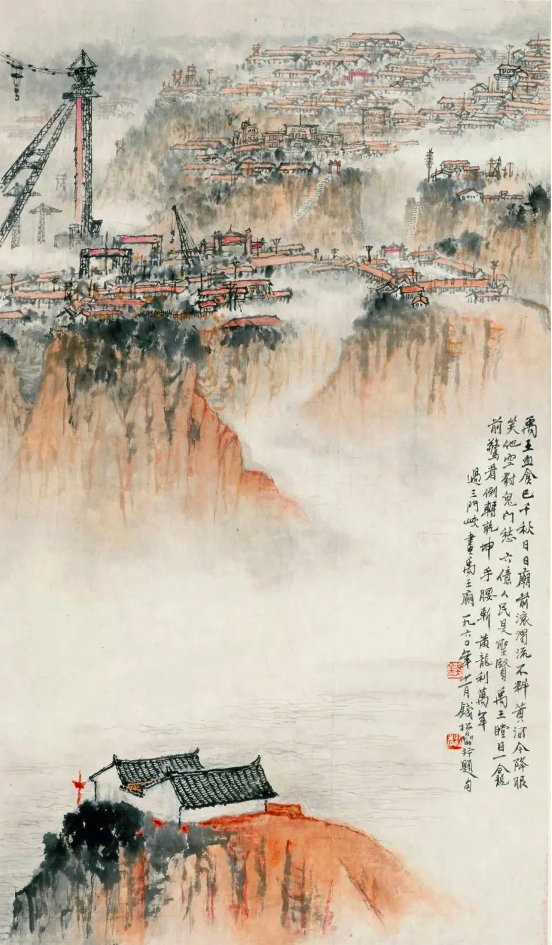

Qian Songyan, another Chinese painting master, was among the group of 13 Jiangsu artists who visited Sanmenxia. One of his most renowned paintings of Sanmenxia is The Great Yu Temple. According to legend, in early Chinese history, Yu the Great successfully mitigated flooding on the Yellow River with diversion channels, making him a figure of worship for those wishing for peace and stability on the river. A temple to Yu has stood in the hills near Sanmenxia for centuries. From an architectural perspective, it is not impressive, but it provided a notable contrast with the cranes and construction across the river. The scene was imaginative and poetic, and Qian also wrote a poem on the lower righthand side of the painting:

The Great Yu has enjoyed sacrifice for millennia, yet the turbid water continues in front of the temple

Today the Yellow River is subdued. We laugh at him for his helplessness when facing the ghost gate

Six hundred million people are now saints, the Great Yu must be startled to see the closure of the dam, the river dragon is cut to bring benefit in the millennia to come.

The Ming Tombs Reservoir

If the paintings of these concrete dams represent the technological sublime of socialist water engineering, artworks of the Ming Tombs Reservoir convey the intensity of socialist labour. Unlike those engaged exclusively as artists at the dam construction sites, many artists in Beijing were mobilised to participate in manual labour on the reservoir.

In 1954, when premier Zhou Enlai visited the Ming Tombs on the outskirts of Beijing, he said: ‘The Ming Tombs is a must-visit place for foreign visitors. It is a pity that there are mountains but no water. If we can build a reservoir with a large body of water, it would be more picturesque’ (Shi and Xu 2008: 68). In the same year, Zhou’s proposal was shared with the Beijing municipal government. In the autumn of 1957, a nationwide water conservation campaign began and became a major program of the Great Leap Forward. In January 1958, the reservoir project was launched in the southeast of the Ming Tombs area. In six months, more than 400,000 People’s Liberation Army soldiers, government employees, students, peasants, and residents of the capital city were mobilised to work on the construction site.

In addition to manual labour—shovelling and transporting earth—students and staff from art institutes in Beijing observed and drew in their sketchbooks. For many, it was an exhausting but stimulating experience. In March 1958, those artists set up an exhibition that included more than 200 drawings of the dam construction site. Unlike conventional art exhibitions that were visited only by social elites, people from all strata of the new socialist society, including ordinary workers, peasants, government workers, and state leaders stopped by and expressed their appreciation and critique of the artworks. A report noted that the exhibition demonstrated that ‘artists had entered the spacious studio of the life of the masses and [socialist revolutionary] struggle’ (Yi 1958: 23).

The Ming Tombs project was an earthfill dam. Unlike concrete dams, which relied on machines, somatic labour was the predominant force at the Ming Tombs reservoir site, and thus became the focus of many paintings and photographs. Work at the site was hard. According to Israel Epstein, a pro-Communist foreign journalist affiliated with the Chinese Culture Ministry:

Every intellectual had seen peasants use a carrying-pole, but few had tried it. The first day, our shoulders would ache badly. The second day they would swell. But on the third, provided we persisted, they would harden and we would be lifting loads we never thought we could attempt. Certainly, it meant gritting our teeth. (Epstein 1959: 4)

Two weeks of backbreaking manual labour deepened those intellectuals’ and artists’ perceptions: ‘They could not regard themselves as individual performers; the rhythm of the huge mass job determined their actions and their pace’ (Epstein 1959: 6). Officials had developed various tactics for labour mobilisation and management, such as organising labour races, identifying labour models, and staging dramatic performances to improve efficiency. Likewise, the state commissioned paintings and photographs of the construction of the Ming Tombs Dam that were intended to generate enthusiasm and defeat fatigue. Unlike the art depicting the Foziling Dam in the early 1950s, scenes of ‘rest’ are non-existent in the visualisation of labourers at the Ming Tombs Reservoir site. For example, the cover page of The Ming Tombs Reservoir Illustration Selections depicts several men ramming earth at the dam site (see Figure 11), reflecting the strength of and team spirit among the labourers.

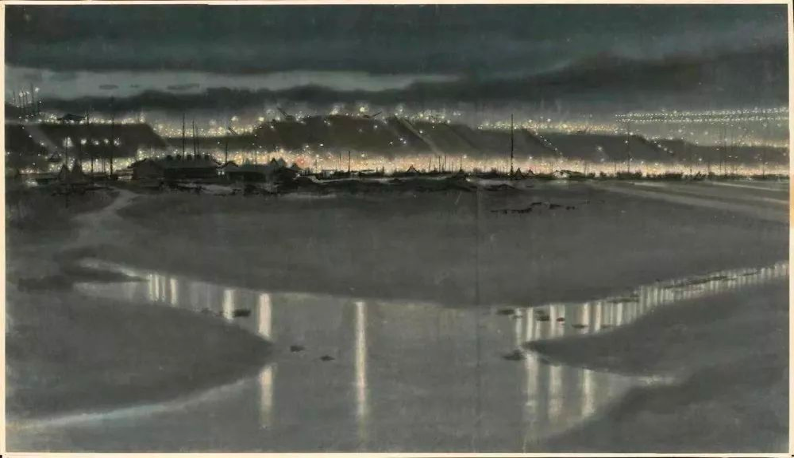

There were also several works of art reflecting the contribution of women at the construction site, which conformed to and reflected the highly regarded gender equality in the socialist political economy. To complete the dam before flood season, labourers were organised to work at night as well as during the day. This provided artists another way to depict the project. Li Hu’s Night Scene of the Ming Tombs Reservoir Construction Site (十三陵水库工地夜景, see Figure 12) skilfully illustrates the intensity and modernity of the project. His masterful employment of ink presents us with an unprecedented night scene of the water engineering campaign during the Mao era.

The Chinese Photographers’ Association invited photographers in Beijing to record the Ming Tombs Reservoir project. Thousands of photos were taken. One of the most highly rated was Chen Bo’s The Heavier the Rain, the Harder We Work (雨越大, 干劲越大, see Figure 13). Pouring rain and people in raincoats carrying poles depict the intensity of labour.

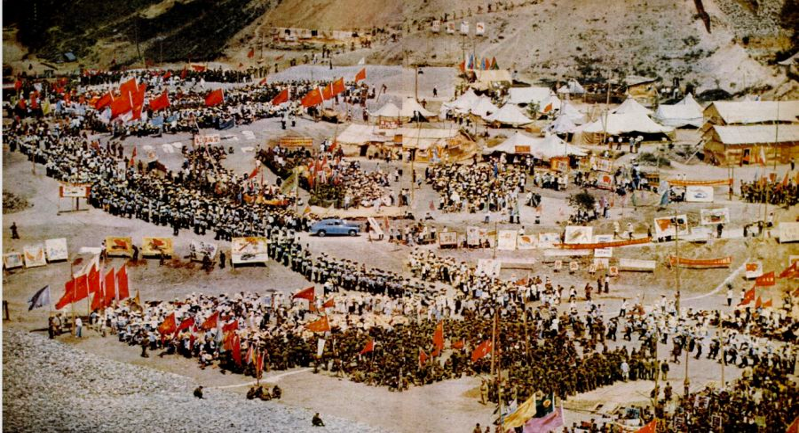

The Chinese Government also invited French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson to visit the Ming Tombs Reservoir construction site, and one of his colour photos was published in LIFE magazine in January 1959. This visual representation of China’s water engineering campaign—red flags, tents, and a multitude of well-organised labourers waiting to be assigned—reached a Western audience at a time when the country was still largely isolated.

The Invisible

In the film The Ming Tombs Capriccio, released in 1958, it is said that ‘labouring is the best rest’. Through water engineering projects, the socialist state not only altered the look of rivers and mountains, but also pushed the limit of people’s somatic capacity. State-sanctioned visual culture effectively served to boost the morale of socialist labourers and inspire a bond between individuals and the State. However, what had been painted, illustrated, and captured on camera was not necessarily the whole picture of water engineering in Maoist China. Large projects such as the Sanmenxia Dam usually came at the cost of the displacement of tens of thousands of residents from the area to be flooded by the reservoir. As a group of ‘unimagined communities’, these people and their homes were invisible under state censorship (Nixon 2013). The government-endorsed socialist realism reflects only part of the reality of these large projects. We must comprehend both the visible and the invisible in our assessment of water engineering in Maoist China.