On the Travel of State Crimes by Algorithm: Chinese Camera Systems in Israel

In one of the opening scenes of Surveillance State, Josh Chin and Liza Lin (2022: 41) describe how then Xinjiang party secretary Chen Quanguo tested the response time of local police in front of a market in the Ürümchi Uyghur neighbourhood of Dawan in early 2017. In less than 54 seconds, a team from the nearest People’s Convenience Station responded to a threat alert. But Chen was not satisfied. ‘With every second shaved off the arrival of decisive force, public safety improves another notch,’ the Xinjiang Daily quoted him as saying. This is what inspired him to build more than 9,000 People’s Convenience Stations across the region and to hire tens of thousands of new security workers to be always on alert, monitoring automation-assisted surveillance systems to apprehend any red-coded or yellow-coded individuals at a moment’s notice. It was part of what Chen referred to as his effort to bury Uyghur ‘terrorists’ in ‘a People’s War of tsunami-like proportions’ (quoted in Chin and Lin 2022: 40). But more than burying Uyghurs, he wanted to create a system of automated apartheid that mirrored and distilled policing systems that were being developed in other parts of the contemporary world in the wake of the Global War on Terror (GWOT), which contributed to an acceleration of the deployment and evolution of these technologies on a global scale.

The history of the GWOT and the Chinese use of such technologies to target Muslims domestically also informs China’s mixed response to Israel’s invasion of Gaza. On the one hand, the Chinese authorities seem to support Palestinian struggles for autonomy (Çalışkan 2023). But, like China’s support of the Assad regime in Syria, it appears that doing so is strategic—a means of fostering international support for the mass internment of Uyghurs in exchange for promises of economic aid (Global Times 2021; AP 2023). This stance is ultimately about opposing US imperialism, which is what they see as a driving force of Israel’s approaches towards Palestinians and other Chinese allies in the Middle East. At the same time, Chinese investment in Israeli infrastructure projects and, perhaps more importantly, colonial policing means that the Chinese Government cannot be too vocal in its support for Palestinians (Wakabayashi et al. 2023). And the obvious resonances between the Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands and Chinese colonisation of Uyghur lands are often present in Chinese policing theory and ethnic policy (Byler 2023b; Lu and Cao 2014).

Industry Leaders

The system Chen was testing in Ürümchi was built in part by the world’s largest camera manufacturer, Hikvision, a colossus that today has a presence in more than 190 countries, and its parent company, China Electronics Technology Corporation (CETC), a Chinese military contractor. CETC was responsible for building the Xinjiang-wide Integrated Joint Operations Platform, which aggregated and assessed data streams from across the region, tracking patterns in movement and social networks to decide who should be detained and when. Hikvision was responsible for more than US$275 million in contracts to build biometric surveillance Safe City systems that were integrated within the platform (Yang 2022). It was also one of the leading tech firms to pioneer software that would automate the detection of watch-listed individuals, placing all populations assessed in a colour-coded stop-light system. Moreover, it developed automated detection parameters such as a ‘Uyghur alarm’ that would read the phenotypes of Uyghur faces to predict their ethno-racial identity (Healy 2022). This type of automated policing is something that anthropologist Allen Feldman (2008) refers to as ‘telling’—that is, drawing correlation between physical features to predict, at the scale of the targeted population, where detected individuals should be placed in relation to a colonial social order. As we will discuss below, this is precisely what Israel is attempting to do.

Since its battle-tested ‘success’ in the Xinjiang system in the late 2010s, Hikvision’s international exports have expanded to the point that they now constitute more than 25 per cent of its revenue (Yang 2022). In many ways, Hikvision’s international success is related to the quality and price of its products relative to those of its competitors. It sells facial-recognition camera systems more cheaply than Japanese and Euro-American manufacturers. But its market share is particularly notable in autocratic states where control of dissent and the colonised is prioritised, Israel included.

Hikvision is perhaps best poised to meet Israel’s intensifying drive to enclose Palestinian life. As of 2021, the company had more than 54,000 camera networks in Israel, with more than 35,000 in Tel Aviv alone (Migliano and Woodhams 2021). According to company sources, its products are used for the surveillance not only of Palestinians, but also of Israelis. For instance, the Israeli Government reportedly purchased 1,000 Hikvision cameras and another 1,000 from Go-Pro and Philips to photograph and monitor voting in their last general election (HVI 2022d). Israeli inspectors installed the discrete cameras on their uniform lapels to supervise voting and vote counting. But as a state contractor to the Israeli military, Hikvision places much of its focus on countering terrorism in the form of threats to critical infrastructure and, through the military’s Red and Blue Wolf programs, identifying and tracking the faces of Palestinians themselves.

These programs are part of Israel’s efforts to automatically assess the threat potential of Palestinians in real time. While the Blue Wolf program focuses on facial-recognition technology to identify individuals, its Red Wolf counterpart is reportedly a dataveillance system used for collecting and analysing a wide range of intelligence, including biometric data, to aid in security operations and decision-making. Essentially, both programs are integrated—like CETC’s Integrated Joint Operations Platform and Hikvision’s Safe City system in Xinjiang—and used to bind Palestinians in place, making them and their digital behaviour searchable in real time (Goodfriend 2023a).

For instance, Hikvision has reported that its cameras have been installed on railways throughout Israel to automate crowd control, monitor suspicious behaviour, and document the movements of certain individuals (HVI 2022b). Train drivers are also monitored for tiredness or distraction. All these systems, which are integrated into the Hikvision network and control centres, use colour-coded alert systems that can be remotely operated. To paraphrase Chen Judelevitz, the co-CEO of Hikvision’s Israel-based distributor, HVI Israel, these alarm systems can be operated through mobile phone applications, integrate with closed-circuit television (CCTV), and alert officers to potential incidents within minutes (HVI 2022a).

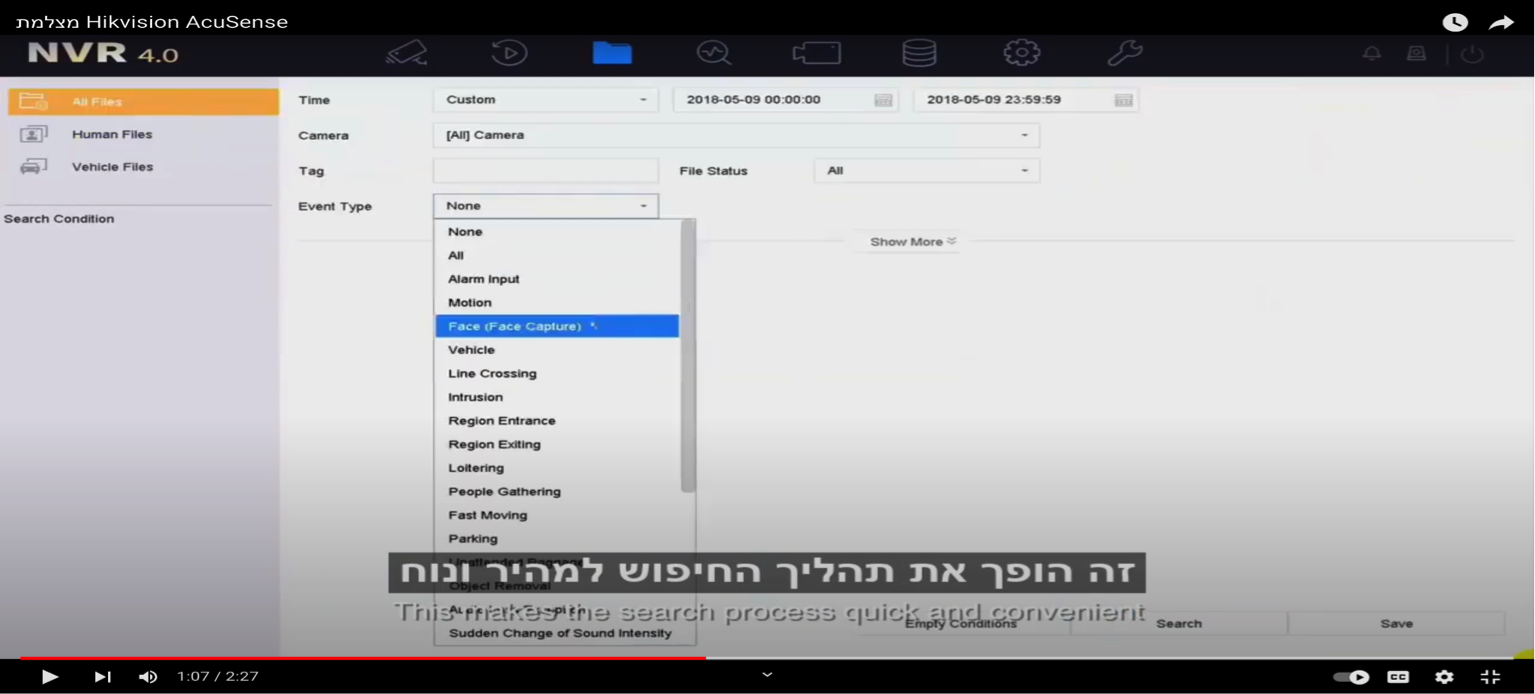

A recent Amnesty International (2023: 57) report confirmed the presence of Hikvision cameras around Israeli checkpoints. In a subsequent report, The New York Times verified that the Blue Wolf system used a colour-coded stop-light alert system that was ‘comparable’ to the use of the system in north-west China (Satariano and Mozur 2023; Mozur 2023). Both reports expressed grave concerns that Hikvision’s cameras were being used in combination with a Mabat 2000 system—an older system of non–automation-assisted surveillance cameras that blanket Muslim neighbourhoods in Jerusalem—to automate forms of apartheid across Israel/Palestine (Amnesty International 2023: 63). As HVI Israel noted, its AcuSense system, which is actively advertised to Israeli agencies and consumers, uses facial-recognition technology to identify people, behaviours, and vehicles (HVI 2022c). This technology—described in a manner eerily reminiscent of the imperative laid out by Chen Quanguo in Xinjiang—drastically reduces the response time of authorities to any type of algorithm-predicted threat (HVI 2022c). As the anthropologist Sophia Goodfriend pointed out in a recent article, drawing on her research with the Israeli military and Palestinians in Hebron, what Israel is doing with its application of computer-vision surveillance systems is enacting many of the same terror-capitalism dynamics that Chinese companies such as Hikvision lobbied for in Xinjiang (Goodfriend 2023a).

Interdependence

The systems of automated apartheid control that are being used in Israel and Xinjiang are significant in at least two ways. First, at a macrolevel they show the interdependence, the learning, between contemporary colonial states in how to best colonise Muslim bodies and minds. Second, they speak to something that might be best described as a colonial uptake of ‘digital resignation’ that is manufactured by multinational corporations such as Hikvision (Draper and Turow 2019). This resignation means that military and police in both Israel and China hand over significant amounts of control of their borders, and their populations more generally, to the predictive capacities of non-thinking machines.

State violence by algorithm results in an overreliance on surveillance to offer settlers security in their dispossession of the colonised. This resulted most obviously in the delayed response to the Hamas attacks on 7 October 2023, but even more importantly in the insulation of Israelis from the reality of colonial domination (Goodfriend 2023b). This distancing is part of what allows state violence by algorithm to be used to justify the brutalisation of entire populations—a normalisation of incarcerating, killing, and maiming Muslim bodies. In the case of Gaza, the use of predictive algorithms to determine targets for what was essentially the carpet bombing of Gaza produced mass civilian death—in what has aptly been called ‘war crimes by algorithm’ (Abraham 2023). In Xinjiang, a related brutality was expressed through the normalisation of the mass internment of regular Muslim citizens (Byler 2023b).

Over time, as the Israelis continue to mimic aspects of Chinese predictive policing tactics, Israeli Arab citizens are being deemed inherently threatening by Israeli police and subjected to arrest due to their online activity, including simple WhatsApp chats, as Israel’s new expansion of its counterterrorism law—which criminalises consumption of ‘terrorist materials’—comes into effect (Goodfriend 2023c). This directly mirrors the types of dataveillance that Chinese police use against Uyghurs. For more than a decade Palestinian movement has been tightly controlled through checkpoints and surveillance and, as Israeli security builds the capacity to assess at scale the encrypted messages of Palestinians, the intimacy and invasiveness of the digital enclosure will only intensify. Ultimately, as Neferti Tadiar (2022) describes in her writing on Palestine, disposable lifetimes are what such systems will produce—as they are intended to.

The authors wish to thank Dr Maya Wind for assistance with Hebrew texts used in this piece.

Featured Image: A training video for Hikvision Israel describes how the company’s algorithmic tools were trained on immense datasets of images of human faces.

References