Afro-Asian Parallax: The Harlem Renaissance, Literary Blackness, and Chinese Left-Wing Translations

Just as China emerged as a revolutionary trope in interwar Black internationalist imaginaries, Shanghai-based journals started to introduce African American writing to Chinese readers. This essay traces early translations of Black literature in Republican-era China and unpacks the parallactic visions as the Harlem Renaissance travelled across the Pacific. Literary Blackness built on and expanded the discourse of ‘minor nations’ and mediated the convergence of transnational left-wing cultures. Chinese translators and critics also reshaped Black literature’s political valency through textual practices, revealing situated differences that conditioned early encounters of Black internationalism and the Chinese left wing.

In 1934, the literary journal Wenxue (文學, Literature) introduced a group of poems written by African American writers in a special issue dedicated to the literature of ‘weak and small nations’ (弱小民族文學專號). Titled ‘Black Wreath’ (黑的花環), this collection of poems takes up the singular heading of ‘Blackness’ (黑人, Heiren) in the journal’s otherwise coherent mapping of the literature of minor nations. In its table of contents, the journal presents a wide range of translated works divided into distinct ethno-national categories, such as Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Turkey, Brazil, and India, putting an emphasis on small and emerging nations in Eastern Europe and West Asia as well as current or former European colonies. This special issue of Wenxue represents one of the earliest attempts to translate African American literature into the Chinese language. The singularity of Blackness in Wenxue’s cartography of minor nations raises a series of questions: What does including Blackness in ‘weak and small nations’ (弱小民族, ruoxiao minzu) mean for the articulation of literary nationhood of the time? How does conceptualising Blackness as a ‘weak and small nation’ suggest new configurations of race, nation, and the task of literature in Republican-era China?

Wenxue’s formulation of literary Blackness should not be conflated with the contemporaneous racial discourse that infused the soundscape, literary experiments, and visual iconography of semicolonial Shanghai. While prominent African American jazz musicians—including Teddy Weatherford, Buck Clayton, Earl Whaley, and Valaida Snow—were in high demand in opulent ballrooms in the city’s French and International quarters, Blackness also became commodified, fragmentary, and primitivised through modernist aesthetic practices and media technologies such as sound films, print commercials, and phonograph records that defined the experience of being modern in Shanghai (Presswood 2020; Schaefer 2017).

In contrast to the sensorial experiences privileged by the entertainment industry, literary translations appeared to present Black voices in their own words and made them legible and accessible to the Chinese reading public. Yet, in so doing, they also removed them from the original context and embroiled them in new meaning-making systems. This essay unpacks the discursive lineage, social formations, and textual practices that rendered the literature of the Harlem Renaissance into Heiren wenxue (黑人文學, ‘Black literature’) in 1930s China. It argues that the articulation of literary Blackness by Chinese left-wing intellectuals built on and expanded the discourse of ‘minor nations’—a development that bears witness to submerged connections between Black America and the Chinese left obliquely via the Soviet Union. Situating Chinese translations of Black literature in their historical context also reveals fissures between the originals and the translations, between authorship and reception. These differences point to unfinished tasks of solidarity-building as Black and Chinese activists and intellectuals envisioned liberation and pursued justice alongside and in relation to each other.

Minor and Injured Nations

Wenxue’s 1934 special issue reconfigured a decades-long tradition of translating the literature of ‘minor nations’ to modernise China. Literary translation was closely tied to ‘the concern with the oppressed’ that increasingly preoccupied Chinese intellectuals’ global focus in the early twentieth century. The desire for world literature, as Jing Tsu (2010: 297) points out, cannot be separated from ‘nationalism’s identification with the weak’, which sought literary alliance in terms of not so much prestige as ‘oppression and survival’. This preoccupation can be seen in the activities of a wide range of translators since the late Qing. For example, A Collection of Fiction from Abroad (域外小說集, 1909), translated by the Zhou brothers (Zhou Zuoren and Lu Xun), primarily focuses on short stories written by Russian, Eastern European, and Northern European writers. The specific wording of ruoxiao minzu gained traction around the May Fourth Movement. Chen Duxiu popularised the term with his essay ‘The Pacific Conference and the Weak and Small Nations of the Pacific’ (太平洋會議與太平洋弱小民族) published in Xin Qingnian (新青年, New Youth) in 1921 (Song 2007: 12–13). In parallel to its sociopolitical usage, the literary category of ruoxiao minzu serves as an antithesis to ‘Western literature’ or the literature of the ‘Great Powers’. It was a gesture of naming that was highly self-referential: ‘The weak seen from the eyes of the weak’ (Song 2007: 17–18).

The evolving formulations of ‘minor nations’ reveal not only the expansion of geographical and knowledge scope but also significant conceptual shifts. In a special issue on the literature of ‘injured nations’ (被損害的民族) published by the influential literary journal Xiaoshuo Yuebao (小說月報, Fiction Monthly) in 1921, which covers Polish, Czech, Greek, and Jewish literature, the editor bases the concept of ‘injured nations’ partially on racialist notions of national character. The introductory essay suggests that to understand the characteristics of the literature of ‘injured nations’, one must pay attention to: ‘1. Which race a nation belongs to (its hereditary features); 2. The particularities produced by the injuries it bears; 3. The natural environment and social circumstances its people inhabit’ (Mao 1921: 2). In contrast, the opening editorial of Wenxue’s 1934 special issue, written by the activist intellectual Hu Yuzhi under the pen-name Hua Lu, steers away from positivist approaches to racial and national difference and instead defines ruoxiao minzu as an identity and positionality indexing power relations. Wenxue’s new definition comprises three distinct categories (Hu 1934):

Oppressed nations (被壓迫民族): native populations in a colony or semicolony and people of colour under white rule. Examples in this category include Indians (South Asians), ‘nations of the Black race’, Malays, Jews, and Koreans.

Minority nationalities (少數民族): non-majority national groups that are not politically independent but maintain a certain degree of economic and cultural autonomy within an independent state. Examples include the Irish, Flemish, Catalans, and Armenians.

Small-state nations (小國民族): nations that have nominally achieved independence but remain economically and culturally dominated by powerful states. This is the largest category, encompassing most of the formerly known minor nations on which Chinese translators focused their attention.

Categorising the totality of ‘the Black race’ as an ‘oppressed nation’, Wenxue espouses a concept of Blackness that transcends geographical and state borders, yet also renders insignificant the different historical experiences of Africans and the African diaspora—in particular, those shaped by the violent aftermath of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. While this understanding shares similarities with strands of Black nationalist and pan-African thought, ‘nation’ here remains the principal category of identification and underpins a teleology of global struggles. ‘Oppressed nations’, ‘minority nationalities’, and ‘small-state nations’, in other words, not only name a present state, but also announce the stages of progression towards formal equality within the family of nations. Modern state sovereignty and national autonomy become both the instrument and the objective that unite the pursuits of ‘weak and small nations’.

Left-Wing Convergence and Reorientation

If the ‘minor’ or ‘injured’ nation serves as a recurrent rallying point for Chinese intellectuals to chart the evolving contours of politically conscious literary world maps, Wenxue’s updated framework was also a product of the convergence and strategic orientation of left-wing cultures in Shanghai in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In fact, Wenxue can be viewed as a reincarnation of Xiaoshuo Yuebao under the support of writers connected to the League of Left-Wing Writers (左聯), an association of progressive writers founded under the support of the Chinese Communist Party. The confluence of left-leaning intellectuals at Wenxue was the outcome of and response to the increasingly repressive political climate. After Mao Dun took over as the new chief editor in the early 1920s, Xiaoshuo Yuebao transformed itself from a largely commercial venture into a platform for ‘the reform and progress of Chinese literature’ (Chen 2018: 117). Its progressive visions were met with increased pressure from its publisher and the journal was discontinued after the bombing of the Commercial Press by the Japanese during the Shanghai Incident. Editors from the Commercial Press, such as Zheng Zhenduo, Mao Dun, and Hu Yuzhi, were looking for a new publication venue over which they could exercise greater autonomy (Huang 2010: 374).

At the same time, writers and publications suspected of communist leanings came under heightened scrutiny, especially after the Nationalist Party intensified censorship of ‘proletarian literature’ (普羅文學) from 1930 to 1933 (Lu 2014: 109). Periodicals officially published by the League of Left-Wing Writers, such as Mengya Yuekan (萌芽月刊, Blossoms Monthly), Beidou (北斗, North Stars), and Wenxue Yuebao (文學月報, Literary Monthly), were banned from publication. Writers affiliated with the league not only faced obstacles in getting their works published. Politically active members had also been arrested, imprisoned, and executed. Publications that had supported left-wing critiques of the Nationalist government would also put their editor’s life at risk. To mention just one instance, Shi Liangcai, the owner and editor-in-chief of Shen Bao (申報), which had published a series of articles by Lu Xun and others criticising Nationalist policies, was assassinated in 1934 (Wakeman 2003: 179–82).

Wenxue avoided an open affiliation with the Communist Party by putting non-league translator Fu Donghua and editor Huang Yuan in the chief editorial positions (Huang 2010: 375–77). The journal thus provided left-wing writers, including many league members—such as Lu Xun, Yu Dafu, Ding Ling, Sha Ting, Bai Wei, and Ai Wu, many of whom were already under surveillance—with a less conspicuous platform from which to navigate the intensified censorship. Yet, the new journal still received warnings from the censors less than one year after its initiation for introducing Soviet literature. The Nationalist Party demanded Wenxue remove ‘left-wing publications’ and contribute to ‘nationalist literature and arts’ (Lu 2014: 111). Translated literature, especially from ‘weak and small nations’, proved less politically sensitive than Soviet literature and original works by Chinese writers with a strong proletarian stance. This is because pro-Nationalist intellectuals were also turning to ruoxiao minzu and Black literature during the same period, but used them to advocate for the party line’s minzu wenyi (民族文藝, ‘nationalist literature and arts’) in periodicals founded to counter leftist influences (Ji 2021: 46; Song 2007: 54). Art critic Zhu Yingpeng, for example, systemically introduced literary works from ‘weak and small nations’ in Qianfeng Yuekan (前鋒月刊, Vanguard Monthly) (Lu 2014: 112). In promoting ruoxiao minzu, the Nationalists sought to interpret literary and artistic creations as embodiments of national spirit and tended to highlight the universal appeal of nationalism (Chen 2015: 108). That is, the literature of ‘weak and small nations’ became a cultural battlefield with heightened political stakes, where left-wing and right-wing forces competed for interpretative power and mass influence under ostensibly the same banner.

Communist Networks and Proletarian Critique

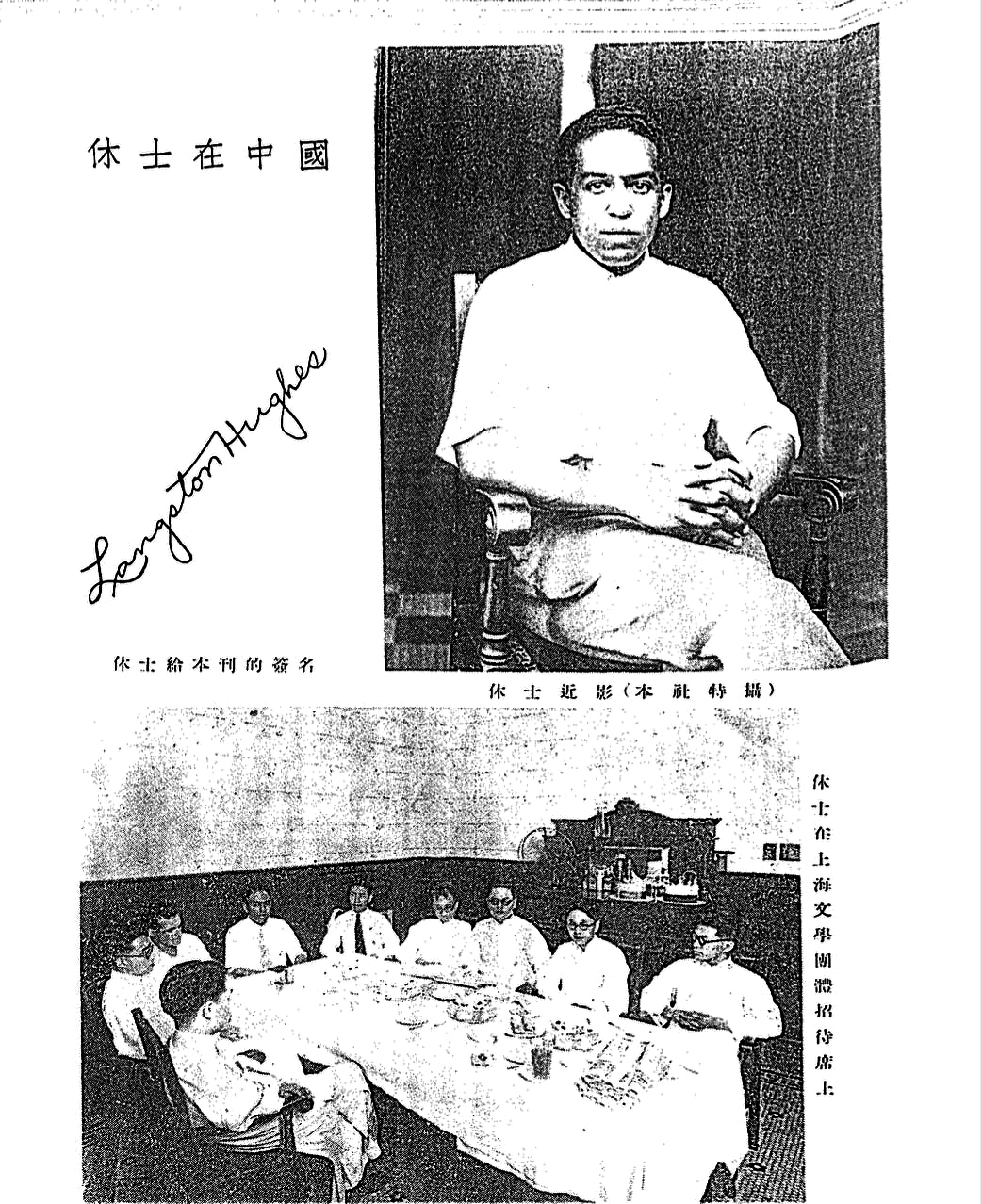

If the Nationalist censors strove to eradicate radical voices from the left by banning proletarian works and reinterpreting the literature of minor nations, leftist writers sought to embed class critiques and communist connections in their translation and critical practices. Wenxue’s inclusion of Black literature in its literary cartography is a case in point. One of the writers introduced in the 1934 special issue was Langston Hughes, a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes visited Shanghai in July 1933 after being invited to the Soviet Union to contribute to the production of a film on ‘Negro life in America’ (Lee 2015: 185). As the first African American intellectual to set foot in China, Hughes was warmly received by the literary circles in Shanghai and embraced as a ‘revolutionary Black writer’ (Gao 2021: 252–57). Although Hughes eventually distanced himself and removed many details of his communist connections from his autobiography, the significance of his presence in Shanghai and the appraisal of his literary output in the eyes of his Chinese contemporaries were closely tied to his involvement and reputation in the transnational communist networks.

In unpublished drafts of his memoir, Hughes recounts the arrangements the radical American journalists Agnes Smedley and Harold R. Isaacs made for him to meet with Madame Sun Yat-sen and the writer Lu Xun, both of whom were under heightened surveillance due to their politics and influence (Taketani 2014: 126–28). The underground nature of these meetings led to unfair criticism of Lu Xun’s absence from Hughes’s public appearances (Cheung 2020). Hughes’s associations with Chinese leftists, on the other hand, entangled him in the Japanese police dragnet and resulted in his deportation by the Japanese authority after he departed Shanghai for Tokyo (Hughes 2001: 259–71). The Chinese writers and journalists with whom Hughes publicly met were aware of and showed keen interest in his Soviet connections. In fact, among the five questions they posed to Hughes during a high-profile lunch featured in Wenxue, three focused on Soviet policies and the cultural scene, one pertained to US proletarian culture, and only one addressed Black American literature (Hughes 2001: 257–58).

Wenxue appraises Hughes’s literary output and the accomplishments of Black American literature primarily through the lens of proletarian culture. Its second 1933 issue spotlights Hughes’s meeting with Chinese writers and journalists along with printed photographs, an introductory essay by Fu Donghua (Wu Shi), and Fu’s translation of Hughes’s travel essay ‘People Without Shoes’. Not among Hughes’s best-known works, ‘People Without Shoes’ focuses on the shoeless Haitian peasant class as a critique of the entrenched racial capitalist conditions epitomised by the light-skinned elites’ obsession with and privileged access to formal attire. Translated into Chinese, the essay can be read as a borrowed commentary on the semicolonial conditions of Shanghai and a proletarian critique of the ruling Nationalist Party. This piece was originally published in the Marxist cultural magazine New Masses, a ‘dynamic center’ of the American literary and political left in the 1930s (Peck 1978: 387). Written in the style of reportage, it reflects Hughes’s ‘leftward shift in his thinking towards a greater emphasis on class’ (White 2011: 110).

In other words, the debut and legibility of Black literature on the leftist Chinese literary scene were predicated on the perceived radical turn of Black writers and their endorsement within the transnational communist and leftist cultural networks. The purview and priorities of Soviet and US critics and publications played an important role in Chinese left-wing writers’ reception of Black literature. For example, it was only after Hughes’s novel Not Without Laughter was celebrated in New Masses and translated into Russian that it gained visibility and started to circulate in China (Ji 2021: 36; Gao 2021: 266). Chinese critics’ assessment of Hughes’s works also heavily draws on review articles and original works published in the Comintern-affiliated International Literature (Ji 2021: 44). Fu Donghua’s (1933: 254) introductory essay, for instance, cites the Soviet critic Lydia Filatova in celebrating Hughes as ‘the only established Black writer to have parted ways with the beaten tracks of petit bourgeois and bourgeois literature’. In line with Soviet and American leftist critics, Fu portrays Hughes’s literary trajectory as one of growth, marked by a laudable turn away from the ‘bourgeois aestheticism’ that characterises much of the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes’s first poetry collection, The Weary Blues (1926), is then criticised as an ‘escapist’ attempt that glosses over the harsh realities of racial oppression with ‘romantic delusions’ (Fu 1933: 255). The commentator further suggests that, though Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927) pays more attention to the Black working class, it was not until his first novel, Not Without Laughter (1930), that Hughes became a writer ‘fully committed to realism’, capable of grasping the ‘realities of Black life with the determination to protest and rebel’ (Fu 1933: 256).

If self-imposed repression and critical neglect of Hughes’s radical poetry and proletarian aesthetics continue to haunt his literary legacy in America (Dawahare 1998; Young 2007), his Chinese textual presence prioritised the ‘red’ Hughes from the very start, almost to the exclusion of his earlier works. Indeed, according to Fu (1933: 256), it is through the ‘complete repudiation of his former creative approach’ that Hughes established himself as a ‘revolutionary artist’. Elevating the political Hughes, Republican-era left-wing discourse championed Black writers’ departure from the perceived bourgeois modernism of the Harlem Renaissance. Chinese translations and literary criticism thus participated in adjudicating the proper form of Blackness by privileging radicalisation over aestheticisation. This polarising tendency infused literary Blackness with enduring tensions between aesthetic style and political content.

‘Heiren Wenxue’ between Black and Red

Hughes’s Shanghai visit gave rise to a new wave of translation of Black literature in China (for an extensive survey of Chinese translations and reception of Hughes’s writing, see Gao 2021). Following Hughes’s recommendation, Wenxue translated an excerpt from Walter White’s novel The Fire in the Flint (1924) in its fourth issue published in October 1933. While the novel follows the political awakening of Kenneth Harper, a Black veteran and physician returning to the American South, this translated excerpt zooms in on the violent encounter between a white mob and the protagonist’s brother Bob Harper, an impassioned youth determined to avenge their sister’s rape. In contrast to Kenneth’s moderate leanings towards racial uplift, Bob, a ‘natural rebel, represents “the militant approach” among southern Blacks’ (Piep 2009: 266). By focusing on Bob’s actions and the tragedy that ensued—he was ultimately lynched by the mob—the translation highlights the irreconcilable nature of racial antagonism and embraces armed revolt against anti-Black violence. Also noteworthy is the fact that Wenxue started to identify Walter White as a ‘Black’ writer in this issue—and hence the category of ‘Black literature’ (Heiren wenxue) in the subsequent translations—as opposed to Hughes being first introduced as an ‘American’ writer. In other words, Blackness became legible in left-wing publications through translational strategies of radicalisation.

The theme of lynching and violence against Black women recurred in Hughes’s ‘Song for a Dark Girl’ (1927), translated as ‘For a Black Girl’ (給黑人女郎) in the May 1934 special issue on ‘weak and small nations’. Notable in this translation are the removal of the musical reference from the title and its anti-religious theme. Lamenting the death of their brutalised ‘black young lover’, the speaker ‘asked the white Lord Jesus/What was the use of prayer’. These albeit minor revisions mirrored the left-wing scepticism of, if not antipathy towards, religion and Black musical practices as revolutionary vehicles (Jones 2001; Presswood 2020). In contrast, Hughes’s literary oeuvre takes a rather sophisticated approach to religion and music (Rampersad 2019). His poetic innovations deeply engage with not only the content but also the form of blues, spirituals, and jazz, connecting vernacular culture to radical critique of structural oppression (Hernton 1993; Gargaillo 2021; Young 2007)

The tendency to secularise religious content is further illustrated in the translation of ‘An Appeal to My Countrywomen’ (1896) written by the poet and abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who was an important precursor to the African American women poets of the Harlem Renaissance (Kemp 2013: 789). A prominent leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Harper embeds multiple references to God—God’s judgement, retribution, and justice—and sin in the 14-stanza poem. The Chinese translation in Wenxue, however, retains only four stanzas and constricts the traces of religiosity to the mere ‘one line of prayer’, significantly shortening the original through a process of secular rewriting. The translation also changed the title to ‘To Women’ (給女人們). The revised title transposes the original appeal to white American women, who would ‘sigh o’er the sad-eyed Armenian’ and ‘mourn o’er the exile of Russia’ but neglect the ‘Sobs of anguish, murmurs of pain’ from Black mothers of the South, to a broadened plea for revolutionary sisterhood potentially applicable in the Chinese context.

As a whole, Wenxue’s translation of Black poems prioritises secular visions of revolution and proletarian solidarity through the exposure and condemnation of anti-Black racial violence, attention to the Black working-class condition, and the call to end oppression by armed rebellion. The rest of the poetry collection consists of Claude McKay’s ‘If We Must Die’ (1919), written in response to the violent incidents during Red Summer; Hughes’s ‘Share-Croppers’, translated as ‘長工’ changgong—a familiar figure in the works of left-wing Chinese writers; and Hughes’s ‘October 16’, which commemorates the white abolitionist John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry in an attempt to start an armed rebellion of freed slaves. The motifs of racial antagonism, class oppression, and revolutionary violence thus thread through Wenxue’s collections of Black literature. These motifs prefigure the postwar socialist literary world system that continues to draw on and adapt cultural expressions of Black radicalism despite the paradigmatic shift away from engagements with ‘capitalist countries’ (Gao 2021: 287–91; Volland 2017: 181).

Heiren wenxue thus names a cultural regime of translation strained by textual and political ambivalences. While literary Blackness acquires conceptual coherence and political clarity through the radicalisation of the Harlem Renaissance, the ‘nationalisation’ of Blackness—that is, categorising Heiren as a subgroup of ruoxiao minzu—delimits the horizon of Black liberation. The logic of formal equivalence underpinning the ‘family of nations’ separates comparable and related struggles into discrete geopolitical units, hindering reflexive critiques of racial modernity that cut across state and ideological borders. It undermines the transgressive and transformative power of radical critiques of racial capitalism and anti-Blackness that had similarly affected China. Furthermore, the cartography of ‘minor nations’ presents a teleological vision of global struggles, whose constituent units were susceptible to the prevailing political priorities and ideological criteria. Its emphasis on totality and inclusion downplays the tensions and discrepancies not only between the designated national traditions but even among the writers themselves. As Yunxiang Gao (2021: 287) points out, while Hughes turned away from radical politics in the face of increased censorship and persecution under McCarthyism, China’s official press continued to champion the radical Hughes from the 1930s ‘as if he were preserved in a time capsule’. In this case, the valorisation of radical Blackness in Chinese left-wing discourse—which became state-sponsored in the postwar years—was ironically indifferent to the complex realities that shaped Black life on the ground.

Parallactic Visions and the Cartography of Possibilities

If Heiren wenxue or literary Blackness in left-wing Chinese discourse remained largely textually mediated encounters, Hughes’s sojourn in Shanghai gave rise to a different Afro-Asian poetics on the other side of the Pacific. In poems such as ‘Roar, China!’ (1937), ‘Song of the Refugee Road’ (1940), ‘Consider Me’ (1951–52), and ‘In Explanation of Our Times’ (1955), Hughes invokes China as a metonym for the global colour line (Lai-Henderson 2020: 91; Luo 2012). Hughes transformed what he saw in Shanghai—the indignities suffered by the rickshaw boys, the racially segregated space of the International Settlement, and the fascist suppression of the communist underground—into verses calling for ‘Little coolie boy’ and ‘Red generals’ to ‘Smash the revolving doors of the Jim Crow Y.M.C.A.’s’ and ‘Break the chains of the East’ (Hughes 1995: 199–200). By protesting not only ‘the impudence of white foreigners in drawing a color line against the Chinese in China itself’ (Hughes 2001: 250), but also the ‘the yellow men’ who came ‘To take what the white men/Hadn’t already taken’ in reference to Japan (Hughes 1995: 199), Hughes incorporates anti-imperialist critique to remap the global colour line—a line that extends ‘From China/By way of Arkansas/To Lenox Avenue’ (p. 386).

Drawing on lived experience to rework Orientalist tropes, Hughes’s China poems sketch an Afro-Asian cartography that connects Black America and China through comparable experiences of oppression and humiliation. Despite Hughes’s formal renunciation of communist commitments in public, China remains a figurative anchor for his poetic visions of a shared future of liberation. In ‘In Explanation of Our Times’, the speaker announces that ‘The folks with no titles in front of their names’, like Negroes in Dixie and coolies in China, ‘are raring up and talking back/to the folks called Mister’ (Hughes 1995: 449). The revolutionary appeal of a distant China is palpable in poems that address momentous events of the civil rights movement. ‘Undertow’, for example, juxtaposes Selma and Peking to ‘The solid citizens/Of the country club set’ (Hughes 1995: 561). In ‘Birmingham Sunday (September 15, 1963)’, the girls killed in the church bombing ‘await/The dynamite that might ignite/The fuse of centuries of Dragon Kings’ and might be awakened by songs ‘yet unfelt among magnolia trees’ (Hughes 1995: 557).

Approaching China as a collective subject and revolutionary metonym, Hughes’s Afro-Asian poetics shares differences and similarities with the discourse of literary Blackness to which his presence and translated works contributed in interwar Shanghai. Whereas the latter relies on systems of literary circulation and textual mediation for transnational left-wing and proletarian cultural formations, the former draws from the embodied experiences of the travelling Black subject to expand the purview of anti-racist and anti-imperialist critique beyond the United States. Both ‘Blackness’ and ‘China’, in this sense, initiate a break from dominant epistemic frameworks and state-centred political concerns, enabling different strategies of disruption in response to different yet interconnected contexts of suppression—anti-communist, fascist, and racially segregated—across the Pacific.

These cultural practices also have their own share of historical limitations. If Chinese leftists reshaped the Harlem Renaissance through selective inclusion and textual modification, the imagery of China in Hughes’s poetics underwent processes of romanticisation and abstraction. Furthermore, neither enjoyed the benefits of sustained dialogue or mutual critique due to the structural separation of discursive genealogies and the mediated nature of these encounters. Heiren wenxue and Black internationalism can thus be seen as constituting a disarticulated unity, whose contingent convergence at the site of interwar Shanghai gestures towards a plurality of liberatory visions, still very much kept apart by ‘the departmentalization of historical and theoretical work along national and supraregional lines’ (Jones and Singh 2003: 3). Attending to these parallactic visions would entail revamping ‘Afro-Asia’ not only as a corrective to ethnonationalist historiography or disciplinary insularity, but more importantly as shared dreams of freedom that remain dormant, untranslated, and unheard in the interstices of the archive.

The author is grateful to the editors for their sustained support, to Professor Andrew Jones and audience members at the Association for Asian Studies panel for their helpful comments, and to Dingru Huang, Pascal Schwaighofer, and Soyi Kim for valuable suggestions on early drafts.

Featured Image: Counter Parallax. Source: Dan Zen (CC), Flickr.com

References