Asymmetries, Heiren Discourses, and the Geopolitics of Studying Race in Africa–China Relations

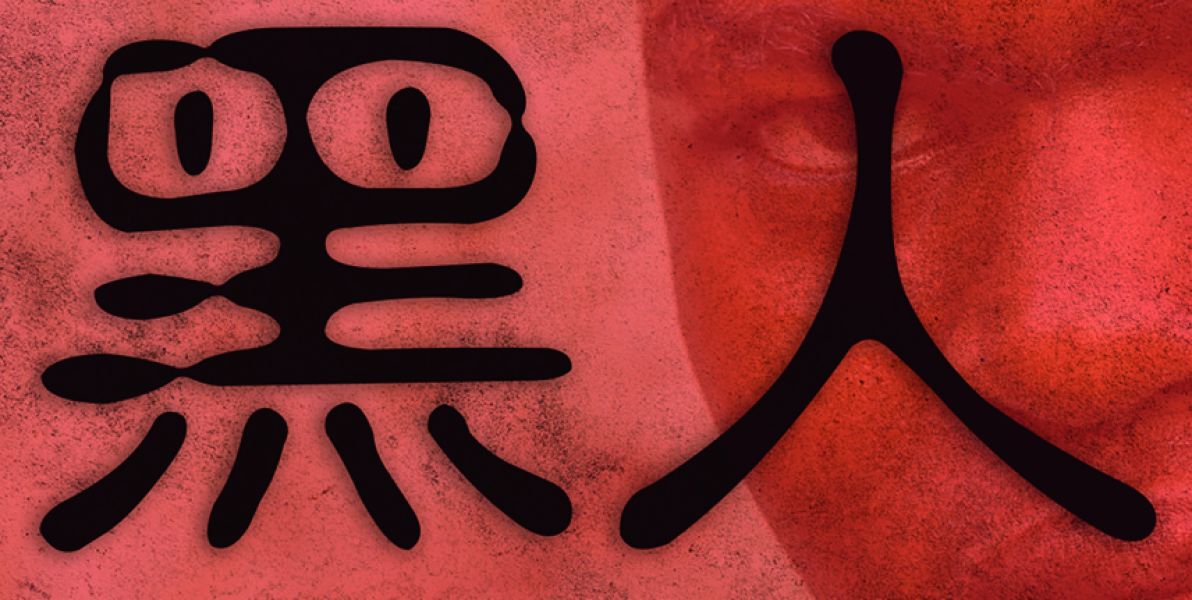

Race is a contentious topic for Africa–China studies. As a white American anthropologist who did ethnographic fieldwork among Chinese migrant entrepreneurs in Tanzania and who currently works in a Taiwanese research institution, my positionality cannot be isolated from the geopolitics of knowledge production in Africa–China relations. In writing about ‘other people’s racism’, recounting Chinese discourses about Heiren (黑人, ‘Black Africans’) and African discourses about ‘the Chinese’, it is too easy to unwittingly reproduce anti-Black racism and anti-Chinese racism while erasing the discursive complicity of one’s positionality both within the academy and during fieldwork. This makes participating in a series on ‘Blackness’ particularly fraught.

I have struggled with how to write about how my Chinese interlocutors talked about Tanzanians. On the one hand, I could not ignore the presence and significance of anti-Black racist discourses, but on the other, I was uncomfortable with voyeuristically reproducing a litany of ‘Chinese’ anti-Black statements. In a published article, I decided to focus on how my Chinese interlocutors talked about Heiren in everyday conversation (Sheridan 2022). The ubiquitous use of this term—which I translate as ‘Black person’ or ‘Black people’—by Chinese speakers to refer to both individuals and a generalised Other seemed conspicuously ‘racialised’ to me. However, I also considered how my discomfort with the phrase implicated my own white liberalism.

My instinct was supported by the findings of another study that, while American migrant entrepreneurs in Kenya shared similar discourses with Chinese migrant entrepreneurs regarding local governance, they, unlike the Chinese, refrained from talking about it through a discourse about ‘Black people’ (Rounds and Huang 2017). As the late Jane Hill (2008) argued, one of the features of what she called white speech is the reproduction of racist discourses while denying that one is racist. The use of ‘Heiren’ by Chinese speakers was more complicated than the mere fact that it was used. Nonetheless, my Chinese interlocutors often seemed to generalise their experiences with Tanzanians of varied backgrounds through the collaborative discursive construction of an ethno-racial Other. In the article I eventually wrote, I wanted to persuade two kinds of audiences to recognise two arguments: those who consider anti-Black racism in China to be self-evident to be more reflective about their epistemologies, and those who argue against unreflectively applying Western theories of racism to Africa–China relations to recognise that racialisation is still relevant. In this piece, I elaborate on the divergence between these audiences and the implications for understanding race and anti-Blackness in Africa–China relations.

The Geopolitics of Knowledge Production about ‘Race’ in Africa–China Relations

While international media coverage has long amplified examples of anti-Black racism in China and among Chinese communities in Africa, Africa–China scholars were slow to seriously address ‘race’ (Celina and Mhango 2022; Al Jazeera 2020; Daly and Lee 2021; BBC 2018; Bromwich 2016; McKirdy 2015; Huang 2021; Lan 2017; Castillo 2020; Adebayo 2021; Fennell 2013; Ke-Schutte 2023; Huang 2020). Earlier ethnographic accounts of racialised interactions between Chinese and Africans either reduced them to intercultural prejudice or ignored them entirely. On the other hand, anti-African or anti-Black attitudes and practices among Chinese individuals are popularly glossed as ‘racism’ without interrogating what race means in these contexts other than a vague sense that any discourse about Africans must ipso facto be a discourse about race. Castillo (2020: 311) observes that the insistence that China–Africa relations must be interpreted through the lens of race is particularly pronounced among ‘Western audiences [who] often racialize conversations about Africa and China’, although African and diaspora audiences also play a significant role.

When Africa–China researchers first discussed race in Africa–China relations, it was often reactive, triggered by specific incidents and scandals—for example, the recurrent use of blackface in Chinese media, including even skits intended to celebrate the Africa–China relationship (BBC 2018). As transnational media events, these scandals have a lifecycle that moves from ‘condemnation’ to ‘contextualisation’ (Schmitz 2021a), especially on the social media platforms used by scholars. When first reported by international—usually Western—media outlets, these incidents are interpreted as revealing the hidden truth of endemic anti-Black racism in China otherwise dissimulated by state narratives of Sino-African friendship. Even scholars who regularly defend Sino-African relations against Western media coverage initially express condemnation and acknowledge there is a problem that must be addressed for the healthy development of the relationship between Chinese and African peoples and economies. This is shortly followed, however, by a stream of commentary contextualising the incident and deconstructing how it has been (mis)represented in Western media (Xu 2018). While these may be more subtle than Chinese media commentaries that racism absolutely played no role in these incidents and that these scandals have been exaggerated by hostile forces, the conclusion is nonetheless very similar: these incidents ‘may not be as racist as you think’ (Castillo 2016; Maya and Ma 2020).

The premise of these critiques is the role of Western knowledge production in mediating Africa–China relations. For example, Xu Wei (2018) argued that calling the use of blackface by Chinese performers during a 2018 New Year gala skit celebrating China–Africa relations ‘racist’ was based on interpreting the performance within the historical context of Western anti-Black racism, and that blackface did not have the same meanings within a Chinese context. Along similar lines, but in the context of Chinese migration to Africa, Barry Sautman and Hairong Yan (2014, 2016) have cautioned against assuming that denigrating discourses among Chinese migrants about African work ethics are a one-to-one reproduction of white settler-colonial discourse about racial essentialism. Instead, they draw attention to Chinese discourses about suzhi (素质) informed by the Chinese development experience—a point further elaborated by Lan (2017). While scholars making these arguments do not deny the presence of racial discourses in Chinese, they caution against the assumption of a homogeneous discourse that fails to consider the different context. Chinese scholars, as described by Schmitz (2021a), ‘take up crucial translational roles, moving cautiously between global critiques of racism and particularist explanations of past Chinese engagements with Africa’.

However, these arguments can also be problematic for several reasons. The first is that they frequently reduce racism to beliefs and intentions that shape behaviour. The second is that contextualising incidents, rather than debunking the role of racism, can ironically become racist themselves, such as explaining how actions by African actors led to particular Chinese actions. Notwithstanding the Chinese context, the pattern is still uncannily like denials of racist intent in Western countries with explicit histories of anti-Black racism. The most serious problem with arguments about incommensurability, however, is that the provincialisation of Western racism, no matter how erudite and informed by critical theories, externalises race and racism as problems incompatible with China’s history. Externalising ‘race’ and ‘racism’ as alien to the national character is not distinct to China but is found even in European countries where these problems are often externalised as distinctively ‘American’. In the postcolonial United Kingdom, as Stuart Hall (2017) and Hazel Carby (2021) argued, the appearance of anti-Black racism was even attributed to the arrival of migrants from former colonies. In arguing that racialised migrants ‘brought’ the problem of race to the United Kingdom, the history of imperialism and race in the formation of contemporary British society is erased. In any case, the consequence is apologism for the ‘unintended’ reproduction of racist images and discourses. Gloria Wekker (2016), writing in the Dutch context of the Black Pete controversy, calls this phenomenon ‘white innocence’.

China did not play a constitutive or direct role in the development of the Atlantic trade system, nor was it a participant in the ‘scramble for Africa’. Furthermore, China was itself a victim of European imperialism during the same period. China’s present wealth also cannot be directly tied to the primitive accumulation of modern capitalism, although one might argue there is still an indirect complicity through the fact that China was dependent on Western capital inflows after 1980. Nonetheless, even excluding that kind of argument, while China may have a more credible claim to ‘postcolonial innocence’ in the Global South, the practical effect of contextualisation is banal and similar to European justifications of the use of blackface.

Notwithstanding debates about whether concepts analogous to ‘race’ and ‘anti-Blackness’ have lineages in traditional Chinese thought, racial nationalism has been a constitutive element within modern Chinese nationalism and anti-Blackness suffused the writings of the earliest modern nationalist intellectuals (Huang 2020; Wyatt 2010; Cheng 2019; Dikötter 1992). While Maoist solidarity with African and African American liberation movements may have also imbued Blackness with revolutionary meanings, especially in Chinese state discourses, an undercurrent of racial nationalism policing the boundaries of the Chinese body politic, particularly at the level of heterosexual intimacy and marital exogamy, was never absent and has remained conspicuous in China’s online Han nationalist communities (Brown 2016; Fennell 2013; Liu 2013; Huang 2020; Cheng 2019). Even if this racial nationalist discourse represents a particular elite stratum of the Chinese public and has been unfairly generalised as the singular ‘Chinese’ discourse, it nonetheless constitutes a significant Chinese discursive context for the racial media events that critiques of Western misreadings of the Chinese context leave out in their construction of a Chinese alterity.

The reticence of Africa–China scholars to discuss race, nuance, is often confounding for non-specialists. As a graduate student, while my Chinese studies advisers understood my caution, my African studies adviser was confused; it seemed ‘obvious’ the interlocuters I was quoting in my dissertation were racist towards Africans. Pushing the other way, Chinese and Sinologist colleagues have questioned the focus on race, considering the topic a peculiar preoccupation of Western scholars.

Fundamentally, the argument that non-Chinese scholars can see the relevance of race where Chinese scholars cannot is itself a colonial expression of representational power; non-Chinese can see Chinese realities that Chinese cannot, due to ideology or censorship. As Huynh and Park (2018: 163) argue, the discourse about ‘“Chinese racism” … is part of a broader discourse about the asymmetry of power—specifically, who gets to make statements about whom’. However, there is a fundamental difference between witnessing Chinese anti-Black racism as a white person and experiencing it as a Black person. In calling out ‘Chinese racism’, white people may situate themselves as enlightened ‘post-racial’ liberal subjects and project ‘racial nationalism’ on to China as evidence of its atavism, but Black people’s experiences of being racialised in Chinese contexts cannot be reduced to the former. As the Senegalese scholar Ibrahima Niang (2017) describes, it was not until he went to China for study that he experienced himself as a ‘Black person’. On the other hand, Africans who have spent time in Europe sometimes describe Chinese attitudes to be based more on curiosity and less overtly racist than in Europe. The Tanzanian traders I know occasionally described Chinese attitudes towards them, particularly suspicion and the refusal of romantic intimacy, to be motivated by what they considered to be the fact that Chinese did not like ‘black skin’. The lack of consensus does not indicate absence. The philosopher Alberto Urquidez (2020) has argued that the ‘victim’s perspective’ should be privileged in defining ‘racism’, shifting the focus from intentions to effects.

Racialisation and the Interpretation of Political Economy

The relationship between racism and victimisation, furthermore, points to a deeper issue. Underlying the debate is a fundamental disagreement about the nature of asymmetry or inequality in Africa–China relations. The controversy concerning ‘race’, like the controversy concerning ‘neocolonialism’, is premised on the assumption that the relationship is unequal. Chinese anti-Black racism is especially problematic to the extent that Africa–China relations more generally are asymmetrical, and the discourse about Chinese anti-Black racism is problematic to the extent that Western knowledge production about Africa–China is asymmetrical, but the nature of the asymmetries in Africa–China relations are themselves contested.

The dominant assumption is that in Africa–China relations, Chinese actors have power, African actors lack power, and racialisation is something that powerful actors do to less powerful actors. This may partially explain why African anti-Chinese discourses are more commonly examined through the lens of anti-Chinese ‘sentiment’ or ‘Sinophobia’ rather than through the lens of racialisation (Castillo 2020). The implicit assumption is that a political economy hierarchy favouring the Chinese is reinforced by ideologies of racial hierarchy. However, ethnographies and case studies of Africa–China relations have consistently complicated dominant assumptions about the nature of the asymmetries (Driessen 2019; Schmitz 2021b). Chinese migrants in African countries are frequently vulnerable and dependent on their African hosts who can make their lives and enterprises easy or difficult. Even in Tanzania—an ‘old friend’ of China—Chinese residents are keenly aware that their passports from the People’s Republic of China attract greater scrutiny from local officials than do the passports of bairen (白人, ‘white people’) (Sheridan 2019). Sautman and Yan (2016: 2151) go so far as to argue that even if Chinese migrants in Africa occasionally express anti-Black racist sentiments, they nonetheless lack ‘political power’ or ‘cultural hegemony’ over their African hosts, unlike African governments, which ‘can regulate, racialize or even expel Chinese’.

The conclusion is problematically partial, however, because Africa–China relations are diverse and non-isomorphic. The power of Chinese bosses over African workers is not isomorphic to the power of African bureaucrats over Chinese migrants, and neither one maps in any one-to-one fashion on to the relationship between China and African states in either geopolitical or economic terms. Significantly, while Chinese migrants are often (relatively) economically privileged, owning more capital than locals, they are also legally and politically vulnerable. When Chinese migrants talk in generalising or negative ways about Heiren, they may be talking about the people they employ or they may be talking about the government officials who regularly visit them to collect ‘tips’.

These distinctions matter to the discussion of racialisation and anti-Blackness because they involve distinct power relations, and it is the interpretation of these power relations that motivates much of the normative contention over the discussion of race. Chinese migrants racialise Africans, but Africans also racialise Chinese. Several scholars have proposed the concept of ‘South–South racialisation’ to capture these dynamics and distinguish them from whiteness that nevertheless shapes the backdrop (Sautman and Yan 2016; Ke-Schutte 2023). As Shanshan Lan (2017) argues, the racialisation of Africa–China relations is ‘uneven’ and unfolds within a triangular relationship vis-a-vis the West.

This situation is not distinct to contemporary Africa–China relations, but is like the historical experience of ‘middleman minorities’ (Bonacich 1973). The contradictory position of middleman minorities in the Global South—economically privileged but politically vulnerable—is the product of European colonialism. Chinese migrant communities in Southeast Asia, like South Asian migrant communities in East Africa, through both colonial legislation and governmentality and their exploitation of opportunities in the colonial economy, became structurally situated between European colonial states and a ‘native’ population. Anticolonial nationalism was often as much directed at these communities as it was at the Europeans (Brennan 2012). Following independence, these communities often remained economically dominant alongside political marginalisation, legal disenfranchisement, and even populist violence.

While a voluminous literature exists vindicating the experiences and identities of these communities as victims of racialisation and state violence, critical political economy perspectives have also been sensitive to interpreting postcolonial racial nationalism through a critique of racialised class formation (Aminzade 2013). For example, challenging duelling critiques of Han Chinese racism and anti-Chinese racism in postcolonial Malaysia, Fiona Lee (2019: 235) emphasises the inherent doubleness of postcolonial racialisation, where Chinese can be ‘beneficiaries of inequality in one moment and targets of violence the next, or even both all at once’. Applied to understanding the relationship between Chinese anti-Black racism and African anti-Chinese racism, these may be productively understood not simply in terms of mutual misunderstandings, but also in terms of mutually constructed racialisations shaped by imperial and colonial histories that continue to shape the contemporary uneven global economy (Lowe 2015). Notwithstanding the complexities and nuances of the Chinese migrant experience in Africa, the political economy of Africa–China relations within the global context is still defined by an asymmetry of capital accumulation and an asymmetry of wealth (as measured by gross domestic product per capita).

However, it was not always this way. During the Maoist era, Africa–China cooperation involved the ‘poor helping the poor’ in both word and deed (Monson 2009). Even after the reform period, during the 1980s, the GDP per capita of several African countries exceeded that of China. The ‘Great Divergence’ between Africa and China is only several decades old, within the lifetime of even the millennial generation. These facts make discussions of asymmetries and racialisation between Africa and China very different from those about Africa and the Global North. Among Chinese and African officials, as well as some Chinese and African entrepreneurs, Africa can be ‘the next factory of the world’, catching up to China as China has done with the Four Asian Tigers, and as the Four Asian Tigers once did with Japan. This is the source of the mainstream developmental optimism that leads writers like Irene Yuan Sun (2017) to dismiss the anti-Black statements of her Chinese migrant interlocutors in Africa as less consequential than what Chinese migrants may contribute in terms of capital and knowledge transfer. Seeing today’s Africans as yesterday’s Chinese implies convergence.

On the other hand, the same divergence between Africa and China since the 1980s that affords developmental optimism among some people also affords vernacular theorisations among other Chinese migrants regarding fundamental differences in ‘culture’ that reproduce the same ideologies of racial hierarchies. In either case, the discourse of South–South cooperation is premised on modernisation. Notwithstanding Chinese development discourses that suggest the Chinese experience is not replicable in an African context, except for the insight about the relevance of local versus Western solutions, lessons from China rather than lessons from Africa are what are predominantly privileged in South–South cooperation. As Kimari and Ernstson (2020) suggest, the discourse of South–South cooperation is still based on dichotomies of development/underdevelopment, which they argue are fundamentally anti-Black: Africa as the undeveloped remainder of the rising Global South.

In any case, whatever view Chinese migrants may hold regarding the future of Africa, the short-term attraction to migrate is often based on the profitability of uneven development. At best, this means an opportunity for them to profit in an environment that reminds them of 1980s China—a situation that is win-win based on the expectation of future convergence. At worst, it assumes that Africa is a space where Chinese but not African individuals can succeed based on their relative skills and resources—a situation in which the conceit of convergence is itself abandoned and economic inequality is again justified by its winners according to theories of racial-cultural hierarchy. Both views can be found among Chinese migrant entrepreneurs.

Situating Heiren Discourse

I have tried to keep all this in mind when making sense of how Chinese migrants in Tanzania talk about Heiren. Rather than arguing for the presence or absence of a distinctive ‘Chinese’ racial ideology, I take the position that racial concepts are produced relationally through discourse. While the impressive scholarship of Johanna Hood (2011) elucidated the semiotics of Hei, Blackness, and African-ness in contemporary Chinese media discourse, I believe efforts to explicate a singular Chinese racial discourse about Blackness may overlook the more innocuous and maybe more insidious workings of everyday discourse.

For me, what makes the term Heiren problematic is less the meaning of the word itself, and more how the word is used in everyday discourse. Among Chinese migrants, ‘Heiren’ are constructed in conversation as a particular kind of ethno-racial type through stories Chinese migrants share about difficult experiences with Tanzanians. These conversations united individuals I considered to hold explicitly racist views with individuals who otherwise expressed relatively nuanced perspectives about intercultural frictions by reflecting shared experiences. These experiences are rooted in the situations in which Chinese most commonly interact with Tanzanians, as employers managing employees and as migrants dealing with government officials—situations exemplifying the situation of Chinese migrants being economically privileged and politically vulnerable.

Despite the anti-racist possibilities of South–South cooperation, it is through the collaborative construction of ‘Heiren’ between Chinese speakers in conversation about these relational dilemmas with Africans that ethno-racial difference is constructed. In validating each other’s experiences with the pithy phrase ‘Heiren are like this’, the heterogeneity of experiences and possibilities is flattened. Furthermore, it is through the resonance between these and global anti-Black discourses that these discussions become discursively complicit with anti-Black racism. By discursive complicity, I mean how individual discourses contribute to other problematic ones independent of the intentions of the speaker (Pagliai 2011). Africa–China relations are embedded within global capitalism and its histories, and there are limits to relativising the racial discourses produced by Chinese speakers. Rather than debating the difference between ‘Chinese’ and ‘Western’ racial ideologies, the more immediate concern is whether the practices and discourses of South–South relations in the present reproduce or can transform Africa’s position in the world.

Featured Image: Heiren. Source: Made in China Journal; original photo by Mark Fischer (CC), Flickr.com.

References