Beijing Evictions, a Winter’s Tale

On 18 November 2017, a fire broke out in a building in Beijing’s southern Daxing suburb, killing 19 people including 8 children. Most of the victims were migrants who had come to Beijing from other parts of the country. According to the local authorities, around 400 people lived in cramped conditions in the two-story structure, which also served as a workshop and refrigerated warehouse for local vendors (Tu and Kong 2017). In the days that followed the tragedy, nearly 20 people were detained over the fire, including managers and electricians of the building.

In response to the tragedy, on 20 November the Beijing government kicked off 40 days of citywide safety inspections, with a particular focus on warehouses, rental compounds, wholesale markets, and other constructions on the rural-urban fringes across Beijing (Zhu and Gao 2017). This led to a wave of evictions from the suburbs of the city. Without any notice, migrants who often had spent years in the capital were told to leave their dwellings and relocate elsewhere in the midst of the freezing north-China winter. While foreign media widely reported on the unfolding of the crisis, what was often overlooked is the outrage that was expressed in Chinese public opinion over the evictions. This essay seeks to fill this gap in three ways. First, it outlines how Chinese civil society attempted to resist the crackdown. Second, it puts forward a novel comparison between the official response to the fire by government of Beijing and that of London in the wake of the Grenfell tragedy. Finally, it considers the implications that the tragedy has had for local labour NGOs.

Voices from Chinese Civil Society

Chinese academia was the first to stand up against the evictions. In the wake of the crackdown at the end of November, more than 100 Chinese intellectuals signed a petition urging the Beijing government to stop using safety checks as an excuse to evict migrant workers from the city. According to this letter, ‘Beijing has an obligation to be grateful towards all Chinese citizens, instead of being forgetful and repaying the country people with arrogance, discrimination and humiliation—especially the low-end population’ (Lo 2017). A couple of weeks later, in mid-December, eight top Chinese intellectuals, including legal scholars Jiang Ping and He Weifang, demanded a constitutional review of the Beijing municipal government’s actions during the mass eviction (Weiquanwang 2017). They published their petition letter to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress online. In this document, they argued that the government had infringed upon five constitutional rights of the Chinese citizens, including land rights, the right to participate in the private or individual economy, private property rights, the inviolability of human dignity, and housing rights. Unsurprisingly, the letter was quickly deleted from Chinese social media (Gao 2017)

Chinese civil society, in particular those labour NGOs that provide assistance to migrant workers, also did not remain silent. According to Wang Jiangsong, a professor at the China Industrial Relations Institute in Beijing, nearly 50 activists from different labour groups signed another petition letter condemning the government campaign (Wang 2017). Far more consequential was a ‘Suggestion Letter’, entitled ‘Beijing solidarity’, that was released on 25 November by a young graduate using the pseudonym Que Yue. Que suggested the establishment of a network of partners to conduct a field survey in the communities nearby in order to connect those in need of help with professional aid agencies. As more and more volunteers joined the cause, Que also set up a WeChat group aimed at drawing a participatory ‘Beijing Eviction Map’ that showed both the locations and number of people affected by the evictions (Qi 2018).

In the days that followed, information poured in from different community actors, and a continuously updated document with information related to available assistance became a focal point of action. In charge of the editing was Hao Nan, director of the Zhuoming Disaster Information Centre, a volunteer organisation set up in the wake of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that specialises in processing disaster-related information and coordinating resources. His job consisted of connecting NGOs, citizen groups, and individual volunteers to work together to collect, check, and spread information. NGOs and the citizen groups conducted investigations in several areas where evictions were taking place and disseminated information about available assistance among migrants. At the same time, volunteers were responsible for collecting useful information online and for checking that the information coming from those who offered to provide assistance was accurate. In an interview with the authors, Hao Nan described the difficulties in assisting the migrants, saying: ‘Some of the migrants actually did not need our help, and some of them thought our information was useless. For example, they needed to find places to live nearby, but we could only find cheap places far away from their neighbourhoods.’ Furthermore, most migrants could not access this kind of information due to the existence of different, and seldom overlapping, social circles on WeChat.

Meanwhile, some NGOs in Beijing began to mobilise autonomously. On 23 November, the Swan Rescue Team (tian’e jiuyuan), an organisation set up in 2016 to provide emergency relief, began to offer migrants free assistance with their relocation. However, after a few days its leader suddenly announced that they would quit the rescue efforts, asking the public to ‘understand that we are nothing more than a particle of dust, what we can do is tremendously limited’ (Qi 2018). The New Sunshine Charity Foundation (xin yangguang) provided funding, medical treatment, temporary resettlement, and luggage storage to evicted migrants. The Beijing Facilitators Social Work Development Centre (beijing xiezuozhe) provided mental health support. Staff from the famous labour NGO Home of Workers (gongyou zhi jia), which was located in the area of the evictions, regularly visited migrants nearby and released updates for volunteers and journalists, but quickly received a warning from the government to cease these activities. Finally, the Tongzhou Home (tongzhou jiayuan), a worker cultural centre first opened in 2009, offered evicted migrants the chance to store their luggage or spend the night there. This went on until 28 November when its director, Mr Yang, was visited by police officers who told him to shut down the organisation. ‘I have worked in a factory, been a street vendor, and run a few small businesses—I know how hard it is to be a migrant worker,’ Yang said. ‘I don’t regret helping them. It was the right thing to do and there is nothing to regret’ (Qi 2018).

Migrants themselves were not silent. According to witnesses and social media posts, on 10 December many of them took to the streets in Feijia village, Chaoyang district, to protest against evictions. Protesters shouted slogans like ‘forced evictions violate human rights’, while others held up home-made banners with the same message (Zhou and Zhuang 2017). The voices of the workers were recorded by Beijing-based artist Hua Yong, who in those weeks uploaded dozens of videos documenting the situation and his conversations with migrant workers on YouTube and WeChat. On the night of 15 December, he posted several videos on his Twitter account entitled ‘they are here’, referring to the police who was at his door to detain him. He was released on bail three days later (AFP 2017).

A Tale of Two Blazes

Though not often linked, the events in Beijing recall the Grenfell Tower fire in London five months earlier. While occurring thousands of miles apart, the two accidents do have something in common. First, they both largely affected migrants. Although no official demographic statistics can be found publicly online, Grenfell appeared to be a very mixed community, with the 71 victims composed of a high proportion of migrants, including those from the Philippines, Iran, Syria, Italy, for example (Rawlinson 2017). Like in Beijing, there were also concerns about a possible underreported death toll, as some undocumented migrants were among the dead but were not accounted for. This is similar to the case of Daxing, where the community primarily consisted of non-Beijing citizens and 17 out of the 19 victims were migrants who had come from others part of China (Haas 2017). The only difference is that migrants in Daxing were interprovincial, whereas in the Grenfell Tower they were international.

Secondly, migrants in both cases were mostly ‘low-skilled’, and from relatively poor and deprived segments of society. Being a social housing block in London, the Grenfell Tower accommodated a primarily low-income community. Xinjian village, where the fire broke out in Beijing, served the same functionality. It lies in the so-called rural-urban fringe (chengxiang jiehebu), where property is generally cheaper and infrastructure is of poorer quality. While white-collar migrants and college graduates can afford to rent in well-established communities, low-skilled (primarily rural) migrants tend to gather in places like Xinjian.

In light of all these similarities, it is even more interesting to compare how the two governments reacted to the fires. Both had set goals to limit the total population of their cities, and both performed fire safety assessments all over the urban area. Nonetheless, as mentioned earlier, in spite of public outrage, Beijing authorities took this opportunity to evict rural migrant workers. Forced evacuation also occurred in other London high-rise apartment blocks that failed the fire safety checks after the Grenfell Tower incident, but the buildings were not torn down and revamped for weeks, during which time the government promised to ‘make sure people had somewhere to stay’ (Holton and Knowles 2017). In addition, the British Home Office also published the Grenfell immigration policy, which grants 12 months initial leave to remain and possible future permanent residency to the migrants involved in the fire.

From this comparison, we can draw two lessons. The first is that previously ridged and clear borders have become subtle and invisible. This applies most clearly to Beijing, where, thanks to the economic reforms, the Chinese household registration system (hukou) is no longer serving as a de facto internal passport system that stops people from migrating. This means that Chinese citizens do not face explicit barriers in terms of moving within their country. But there are invisible walls in terms of welfare entitlements, as the hukou system still links provision of social services to the place of registration. And just as immigration policy in developed countries is more selective towards highly-skilled migrants, the conditions for granting a local hukou to internal migrants in big cities like Beijing are also geared towards attracting the wealthy or the highly-educated. As a result, those low-skilled internal migrants are highly unlikely to obtain a Beijing hukou, and the Beijing government is not obliged to provide better housing for them. They are treated as second-class citizens in their own country.

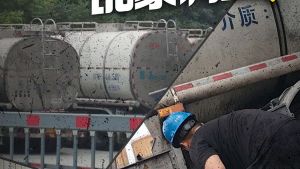

The invisible border is also seen in the living space of those low-skilled migrants. In China, most rural migrant workers have to reside in island-like slums whose connections to other parts of the city are cut off. For instance, the accompanying photo was taken in December 2017, when one of the authors visited Houchang village, a slum known for being home to many migrant drivers and chauffeurs. On the left side of the picture is the village where migrants live. The rooms are so small that some furniture has to be put outside. Just to the right of the road lies an advanced residential complex with private basketball and badminton courts. Behind this newly built accommodation is the Zhongguancun Software Park, where several high-tech IT companies are based. Right at the crossing, we saw a rubbish truck collecting waste from the software park, but just one street apart, in the village, there was not even one trash bin. We could not get an aerial view of the village, but one can easily imagine a segmented landscape, with the village area being stripped of access to public services and composed of basic infrastructure, but surrounded by fancy modern buildings within just ten meters of its perimeter. Every morning, migrants flock out to the city as drivers, delivery workers, etc., providing low-cost labour. In the evening, when they are supposed to relax, they squeeze back into the village. This scenario recalls the science fiction novelette Folding Beijing (Hao 2015), in which the city is physically shared by three classes, who take turns living in the same area in 48-hour cycles.

Another lesson that we can draw from the comparison between London and Beijing is that under all migration management systems, it is low-skilled migrants who bear the brunt of the catastrophe whenever a disaster happens. High-skilled workers are rarely affected and can easily work around the situation, even when they themselves become targets. While the dichotomy between high-skilled and low-skilled seems to be neutral and focuses on learning rather than inherited qualities, we should always bear in mind that when people are low-skilled it is largely due to institutionalised factors, not simply a matter of bad luck or bad choices. Taking education as an example, big cities are rich in experienced teachers, museums, opportunities for international exchange, etc.—a situation that allows urban citizens to receive a much better education than that available to people in under-developed areas. Awareness of this is a first step to prevent disasters like the Beijing fire from becoming the justification to victimise already vulnerable segments of society.

New Workers, New Priorities

With a view to labour NGOs, the evictions have at least three layers of meaning: first, they highlight structural and demographic changes in the Chinese workforce; second, they show that there is an urgent need for labour NGO activists to find new strategies to conduct their activities; and third, they demonstrate that the political context is swiftly changing. According to our personal observations, migrant workers who dwell in Beijing’s urban villages work in a variety of industries that go far beyond traditional occupations in small retail, decoration, domestic work, vehicle repairing, etc. Today’s migrants work in industries that are characterised by the logics of modern large-scale capital investment, including logistics, delivery, and real estate. Although the specific distribution of employment by industry still needs to be investigated thoroughly, the abundant supply of information, as well as the increasing ease of transportation and communication, have already made it possible for the urbanised workers to respond promptly to challenges coming from changes in government policies.

However, while the migrants themselves are increasingly able to respond quickly in the face of new threats, the response of labour NGOs—the traditional champions of migrant workers—to the evictions reveals the serious limitations of their current organisational approaches. It is well documented that labour NGOs first appeared in China in the late 1990s, and went through a phase of expansion in the Hu and Wen era, especially in the years that preceded the financial crisis. These NGO practitioners are first and foremost professionals in the fields of the law, social services, or occupational safety and health. To this day, these organisations mostly focus on providing individual legal aid, carrying out legal training and legal dissemination among worker communities, investigating violations of labour rights in factories, and organising recreational activities aimed at the working class. Through these activities, they are able to create short-term networks among their clientele, fostering fledgling feelings of solidarity.

The mass evictions clearly exposed the deficiencies of such approach. On the one hand, these labour NGOs have already been hit by a harsh wave of repression in 2015 and 2016 that has severely undermined their ability to operate (Franceschini and Nesossi 2018). While those organisations and individuals that campaigned for a more militant activism based on collective bargaining today no longer exist or are unable to campaign, the remaining NGOs have no choice but to resort to self-censorship and limit their activities in order to survive. In addition, the core members of these organisations tend to consider themselves professionals rather than activists, and find themselves under considerable pressure from their families, peers, and state officials to avoid overly sensitive work. There are also clear class differences between NGO staff and the workers they assist, with the former largely belonging to the urban middle class and having a white-collar background. This gap was evident during the evictions, when the information and assistance services provided by these NGOs scarcely broke through social barriers to reach the workers.

While labour NGOs are marred by these constraints, individual agents appear to be far more active. Not only labour activists, but also ordinary middle class people decided to step up when confronted by the situation that migrant workers faced in Beijing during the evictions. They felt compelled to appeal for the rights of the urban underclass. For the first time, information and articles concerning labour and the ‘low-end population’ grabbed the spotlight on various social media platforms normally used primarily by middle class users. This resulted in an unprecedented prominence for the ‘underclass discourse’ in the public discussion, bringing together activists from intellectual backgrounds as diverse as Marxism, Maoism, and liberalism

While labour NGOs are becoming increasingly powerless, the actions of these individual citizens provides some hope in the otherwise stark reality in which migrant workers remain trapped in a dire situation under increasing pressure from the world’s most powerful and undisguised police state. In light of this, it is our urgent duty to adapt to the rapidly changing socio-political climate, and make new alliance aimed at forging solidarity across different sectors of society, and developing more effective strategies and organisational models to support marginalised migrant workers and others who are falling victim to state repression in contemporary China.

Photo: Evictions in Beijing, South China Morning Post

References