Human Rights in China: a Conversation with Eva Pils

The topic of human rights is highly contested and subject to a range of diverse interpretations. This is even more apparent in authoritarian contexts like China, where political leaders pass progressive laws and regulations, and sign international treaties, while at the same time regularly cracking down on those citizens who attempt to proactively claim the very rights assigned to them by officialdom. In this conversation, Eva Pils—author of Human Rights in China (Polity, 2018)—and Elisa Nesossi discuss the significance of human rights in today’s China. They look at the challenges that both discourses and practices of human rights pose, not only to the Chinese authorities and citizenry, but also to those outside the country.

Elisa Nesossi: In your book, you describe the articulation of human rights in China as a vibrant and important social practice that is not entirely dependent on formal institutions and that is partly taking place outside the institutions of the Party-state. Drawing on a vast array of very different sources and extensive fieldwork in China between 2010 and 2017, you offer a compelling view of the ways in which rights defenders in contemporary China use the concept of rights (quanli) or human rights (renquan), as well as official or establishment discourses about rights. Why do you feel that it is imperative to engage with the ‘vernacular’ of human rights in order to understand the trajectory and practice of human rights in China since the 1990s?

Eva Pils: I think that it is important to keep making the case for human rights and the values of equality and freedom that underpin them. Human rights have wide appeal and are universal. Yet the Chinese government likes to portray human rights as a culturally alienating imposition by hostile foreign forces. Scholars in and outside China who see human rights discourse as a form of cultural imperialism tend to support this—in tendency—relativistic narrative. This relativistic argument needs to be challenged.

There was a time when the government seemed more committed to human rights progress than now. In the wake of its crackdown on the 1989 democracy movement, it had hoped to re-gain acceptance and trust by adopting human rights language and limited, gradual rule of law reforms. But while this allowed human rights defenders to emerge as a force—a movement, even—in Chinese society, Xi Jinping’s government is now attempting to shut this movement down, because it does not want to continue liberal reforms. It persecutes rights defenders with unprecedented vigour, while representing itself as a superior alternative to liberal democracy, at best using ‘human rights’ in purely rhetorical ways.

So it is now all the more important to show that ordinary people seeking justice have taken to using human rights discourse and have made it their own without any hesitation. As I describe in my latest book, they relate the idea of rights held just by virtue of being human to conceptions of justice that can be found in the pre-modern Chinese tradition, incorporating both into their language and everyday practices. This is why you can see people assert ‘human rights’ (renquan) and ‘wrongs’ (yuan) in the same breath. Even as the Party-state’s authoritarianism deepens, the social practice of human rights persists as a real and forceful challenge to the system that will not go away. It testifies to the strength of ideas that are now ever more embattled—not only in China.

EN: ‘China has lifted millions out of poverty’. This is one of the arguments frequently used by the Chinese authorities to claim achievement in the protection of socio-economic rights and challenge their critics. It is a claim that the Party-state also refers to when arguing that socio-economic rights—the right to subsistence (shengcunquan) in particular—must be improved before civil and political rights can be addressed. To what extent do you feel that this overall argument and developmental perspective are tenable, or even useful?

EP: Development is an important goal, but claiming that GDP growth is the answer to China’s socio-economic rights issues is wrong. When Mao Zedong died in 1976, China was impoverished and weakened as a result of Mao’s disastrous governance mistakes. Tens of millions had died of famine in the 1950s, and the 1960s and 1970s had brought turmoil and violence. The liberalising reforms of the post-Mao era undoubtedly allowed China to recuperate and recover some of its position in the global economy which, by virtue of its comparative size, one might say it ought to have. Many emerged from dire poverty to build modestly prosperous lives. But these millions of people hardly waited to be ‘lifted’: they lifted themselves as soon as it became possible. In that sense the claim that ‘China has lifted millions out of poverty’ is at best confused.

The Party-state likes to claim agency and take credit for poverty alleviation and economic growth because this is how it hopes to justify continued, repressive one-party rule. In human rights terms, it claims that it has protected socio-economic rights while deferring civil and political rights reforms. But the fact that continued repression coincided with growth does not mean that repression was required to achieve growth or indeed that growth justified repression—in fact, growth had ensued when the Party-state relaxed its control over people’s lives.

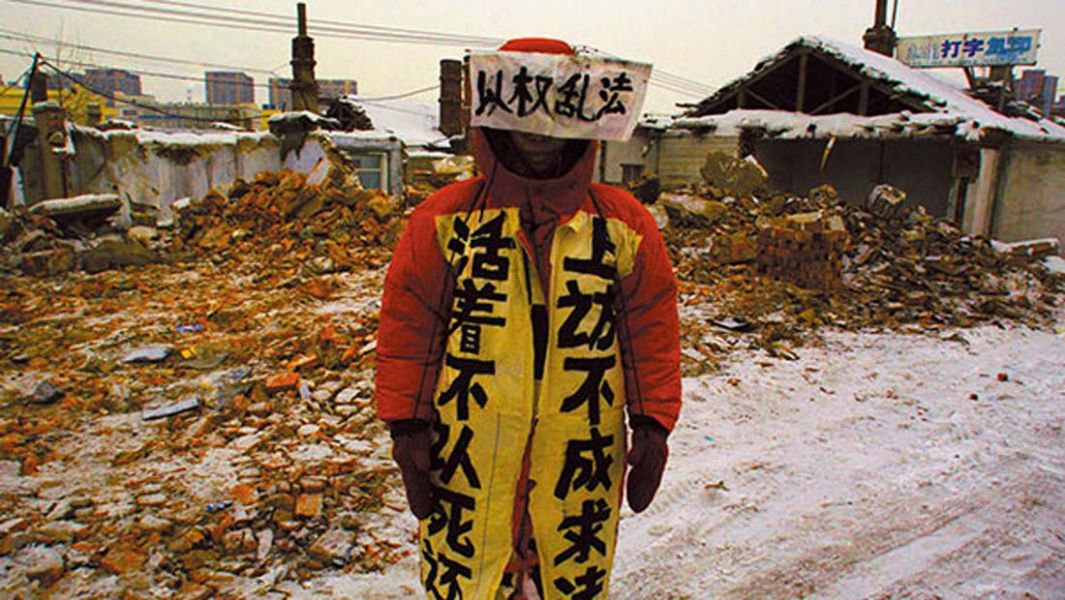

It is also important to point out that GDP growth—making everybody better off in the aggregate—does not equate to protecting socio-economic rights. There are two reasons for this: first, the ‘state capitalist’ model of growth has produced many individual victims of socio-economic injustice. China’s real estate boom, for example, is premised on a huge forced redistribution of land that has driven hundreds of millions of people out of their homes and off their land—which is needed for property ‘development’. Complaints against forced evictions, inadequate compensation, and other rights violations in this context are not only often useless, they can also trigger further persecution and abuse. Second, growth has relied on ruthless new social divisions exacerbated by discriminatory state policies. The Party-state is far from honouring its human rights obligations, for example, toward the children of rural migrant workers, who are routinely denied access to education in the cities where they live. So, the argument that China has lifted millions out of poverty distracts from the very real socio-economic rights violations we should be focussing on.

EN: In today’s China, public expression is rich and vibrant. You rightly say that ‘[expression] is so widely available, it has so many different authors, and it so easily transcends—or blurs—the boundary from private to public.’ And, citing legal sociologist Yu Jianrong, it seems that nowadays ‘everybody has a microphone’. However, while China still tightly control freedom of expression, the techniques used by the Chinese authorities to exert this control have also become smarter. What do you mean by this, and what implications does it have for human rights?

EP: Repression has become smarter through technological control and manipulation. Consider how much the way in which the Party-state infringes rights has changed. ‘Classical’ twentieth-century Communist Party censorship and infringements of freedom of expression, thought and conscience, information, association, and political participation tended to be overt and hard to miss: they were evident from the use of strict censorship of the press, ubiquitous visual propaganda and megaphones blaring out party slogans, for example. Totalitarian twentieth-century infringements of liberty and integrity of the person were usually equally flagrant: they took the form of internment, incarceration, assassinations, and torture.

Much of twenty-first century repression is different, subtler and smarter. Today, the country is highly consumeristic, in many ways more diverse and individualistic, and brimming with media content; but there is still a vast array of censorship rules, as well as sophisticated practices of online content suppression and deletion. Even social media, with its opportunities for individually generated and distributed content, is affected. There is so much imagination and creativity, yet the Party-state operates a complex system of ‘thought guidance’ that includes the manipulation of social media discussion—think for instance about hired ‘trolls’ and the ’50 cent party’. There are many pretend-participatory mechanisms such as ‘public consultation’ preceding evictions; but the Party calls the shots on everything it decides to control, and accountability though public scrutiny or legal procedures is minimal.

Technology has helped the Party update not only its censorship and thought guidance strategies, but also the more individuated means by which it controls ‘elements of instability’ such as human rights lawyers and invades their personal liberty. I do not just mean the updated forms of (white) torture that leave little or no trace, or the sophisticated use of medication to make targets ‘confess’ to wrongdoing, but also the vastly more sophisticated surveillance techniques that nowadays leave you unsure about how free you are, because your movements, consumer decisions, communication, and interaction with others can be tracked anywhere, anytime. The result of this is that in many ways control of the individual person has become less visible, cheaper, and more pervasive and effective. While this is bad for human rights advocacy—and advocates—they, too, have learned how to use smarter forms of advocacy, e.g. by more effectively reporting cases of abduction, detention, and torture, and by connecting to each other and to groups outside China via Internet block circumvention tools.

EN: In the conclusion of your book, you argue that human rights advocacy and repression have important transnational dimensions, and that China’s rights abuses have become a global issue. This means that both advocacy and repression have ‘gone global’, increasing the complexity of the political struggle for human rights. In this context, what are the challenges that the human rights situation in China presents to those outside the country?

EP: For a long time advocacy was more transnational than repression: what has been called ‘the global human rights movement’ entered China in the form of civil society organisations and foreign-sponsored programmes from the 1990s onward. It helped Chinese society transform and allowed Chinese rights defenders form alliances with actors abroad.

China under Xi Jinping has not only sought to stop this, as noted earlier; it has also embarked on a massive outreach programme. This means that, along with infrastructure investment and exchange, Chinese repression is also more frequently exported beyond China’s borders.

I do not only mean when publishers and rights defenders are abducted and brought back to China from adjacent countries. I mean also the practice of keeping tabs on all Chinese nationals abroad and the more subtle influence cultivated by collaborating with institutions and organisations abroad. One might think that bankrolling think tanks, paying for propaganda ‘supplements’ in western newspapers, or funding students and researchers to spend time abroad cannot possibly be harmful to societies where human rights and liberal-democratic values are supposedly entrenched. In reality, as we become beholden to Chinese government support or dependent on Chinese government permissions, we become vulnerable to self-censorship and complicity in repression by the Chinese government. A complacent failure to recognise our vulnerability can undermine our commitment to human rights values.

The way we think about human rights has not quite caught up with this situation yet. People still tend to think of the human rights situation in other countries as problems involving perpetrators and victims ‘over there’. But many of these problems are here now, they are becoming ours as we are ever more implicated and directly responsible. I think this is one of the greatest challenges to liberal democracy today.