Documenting China’s Influence

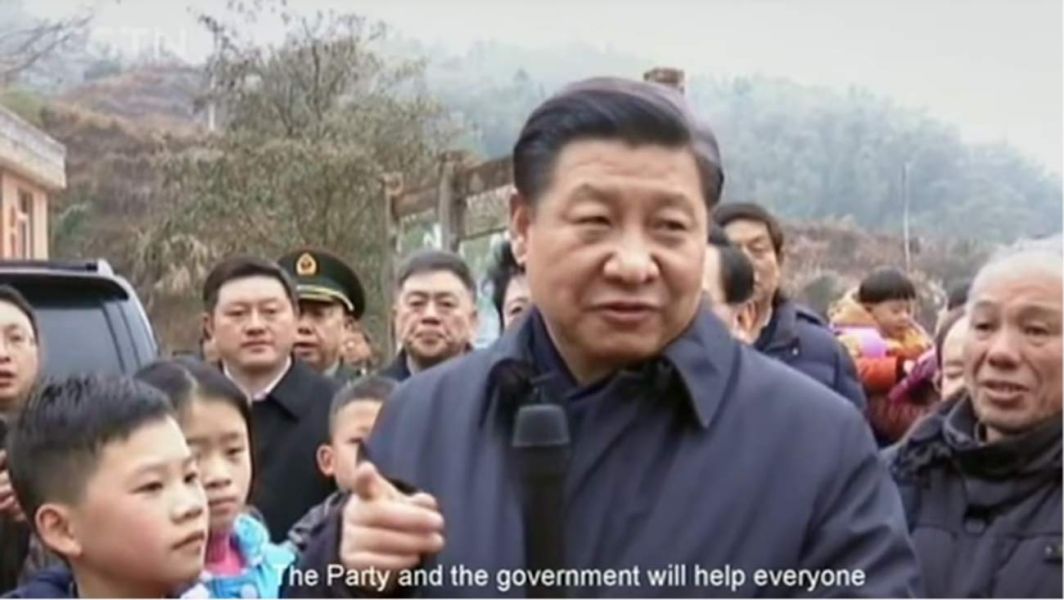

One year ago, on the eve of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Nineteenth National Congress, the Discovery Channel, one of the world’s most recognisable cable television brands, aired a slick documentary series presenting China as a dynamic nation on the cutting edge, under the stewardship of its ‘people-centred’ President, Xi Jinping. The programme, China: Time of Xi, was hosted by international personalities, including American architect Danny Forster and Australian biomedical engineer Jordan Nguyen (Discovery 2017). Produced for Discovery by Meridian Line Films, which identifies itself as a ‘UK-based independent production company’, it aired in 37 countries and regions across Asia, reaching tens of millions of viewers (2017).

By most accounts, the series was simply good programming—a timely and relevant response to China’s political event of the year. A report in the Straits Times, Singapore’s English-language daily, quoted creative director and executive producer Liz McLeod, the founder of Meridian Line Films, as saying that ‘this is obviously a moment when Discovery’s audiences will be wanting to know more about President Xi and about Chinese policy, and so it was a very good opportunity to make this series now’ (China Daily 2017).

Nesting China Dolls

Take a more critical look at the circumstances surrounding China: Time of Xi, however, and the plot quickly thickens. The series was in fact the product of a three-year content deal inked in March 2015 between Discovery Networks Asia-Pacific and China Intercontinental Communication Centre (CICC), a company operated by the State Council Information Office (SCIO) — the Chinese government organ, sharing an address with the Central Propaganda Department’s Office of Foreign Propaganda (OFP), responsible for spearheading its official messages overseas (Gitter 2017). The news chatter surrounding the series came almost exclusively from official state media, which nevertheless took pains to persuade readers of its independence (People’s Daily 2017). Even the Straits Times article offering the quote from McLeod was sourced from the China Daily, the official English-language newspaper of the SCIO (China Daily 2017).

The UK-based Meridian Line Films was yet another case of nesting dolls ending with the CICC and the SCIO. In its annual report filed in July 2015, Meridian Line lists as company directors both Jing Shuiqing, CICC’s deputy director, and Wang Yuanyuan, its creative director (Companies House 2015). According to the same report, 85 percent of Meridian Line shares were held by a company identified as ‘China International Communication Center Ltd,’ a name CICC frequently uses interchangeably with China Intercontinental Communication Center (China Daily 2007). Chinese company records show that the CICC directed by Jing Shuiqing, its legal representative, is fully owned by China Intercontinental Press (SAIC 2000), a company held by the Central Propaganda Department (SCIO) (SAIC 1994). That company’s legal representative is Chen Lujun, currently deputy director of the News Bureau of the Central Propaganda Department—and therefore one of the country’s top censorship officials for film and the news media (though he regularly appears in the media wearing another hat, as a film industry executive) (DocuChina 2017).

The point of this rapid rewind through what was billed last year as an independent television production is to demonstrate one of the more subtle means the Chinese government has at its disposal to influence the narrative globally about its domestic politics and its foreign policy—international film co-production.

From Soft to Sharp Power

In a paper released the month after China: Time of Xi was broadcast across Asia, authors Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig (2017) introduced the term ‘sharp power’ to describe the efforts of countries like China and Russia to ‘distract and manipulate’, as opposed to the hard power of economic inducement or outright coercion, or to the appeal and attraction of soft power. Walker and Ludwig cited such ‘borrowed boat’ tactics as the insertion of China Daily supplements like ‘China Watch’ in foreign newspapers, or the airing of documentaries produced by China Global Television Network (CGTN) on channels outside China. These cases involve utilisation of domestic media channels for what is more or less transparently Chinese state content.

By contrast, the co-production model is far subtler, and far more recent. As scholar and documentary filmmaker Ming Yu noted in 2017 (Yu 2017), the 2011 release by the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) of a policy document titled ‘Opinions on Accelerating Development of the Documentary Industry’ was a key turning point for international co-productions (SARFT 2012). According to the policy, the ‘energetic advancement’ of the documentary industry would ‘have great significance for boosting international cultural dialogue and cooperation, advancing the going out of Chinese culture, and raising Chinese cultural soft power.’ Outside official CCP discourse, talk of ‘culture’ may seem warm and inviting. But for China’s leaders culture is twinned with the language of ideological dominance, a link we can spot clearly in President Xi Jinping’s August 2013 speech to his first propaganda and ideological work conference, where he described ‘Chinese culture’ as a tool of international discourse power (China Copyright and Media 2013). As Li Congjun, the director of the official Xinhua News Agency, wrote at the time: ‘In the world today, whose communication methods are most advanced, whose communication capacity is strongest, determines whose ideology, culture, and value system can be spread most widely, and have the greatest influence on the world’ (Li 2013).

An Illusion of Independence

Since 2011, CICC has racked up a long list of successes in rolling out its cultural programming, aided by international co-production partnerships. To offer one more recent example, there is The Story of Time, a documentary co-produced by CICC, Guangxi TV, and Vietnam Television (VTV)—Vietnam’s national television broadcaster. The film builds on the recollections of teachers and students from Vietnam who spent time in Guangxi to convey what a description by CICC calls ‘the deep friendship between China and Vietnam’ (VideoChinaTV 2017). The programme was timed to air both in China and in Vietnam during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit held in Da Nang, where Xi Jinping’s speech followed that of US President Donald Trump (Tan 2017).

Unlike the ‘borrowed boat’ approach, or the outright launch of Chinese-produced programmes and channels overseas—such as CGTN America—the co-production model allows China’s state propaganda apparatus to piggyback on the trust and credibility that domestic or regional broadcasters such as Discovery Asia or Vietnam Television have already established with their audiences. Further, it helps project the illusion of distance between the Chinese state and the production process, such that the ‘independence’ of documentaries like China: Time of Xi can be taken seriously, despite obvious alignment with state propaganda messages. That is, until we take the often simple step of lifting the veil—looking, as I did above, at the short trail of breadcrumbs leading back to the centre of China’s propaganda regime.

When it comes to international film co-production, the veil is almost never lifted. Which leads us to the final, and perhaps most important, advantage of China’s continued engagement with production cultures overseas through enterprises like CICC: the normalisation of the Chinese state as a creative partner and financier.

Normalising Propaganda

In September 2015, when the executive vice president of National Geographic Channel (Asia), Simeon Dawes, unveiled the broadcast slot for China From Above, a two-part documentary produced jointly with CICC, no one noted the oddity of the fact that Cui Yuying, a deputy director of China’s SCIO, was there to address the audience, saying the documentary would ‘provide a better understanding of China for foreign audiences’ (China.org.cn 2015). Similarly there was no media coverage of the fact that the co-production partner was fully owned by the Central Propaganda Department, of which Ms. Cui was also a deputy director.

Likewise, Realscreen, an international magazine covering the television and non-fiction film industries, could write ingenuously in June this year that China was ‘making a big comeback as a co-production partner’ at France’s Sunny Side of The Doc, one of the world’s leading markets for documentary and factual content—despite the fact that all of the partners named, including CICC, were run by the Chinese state (Bruneau 2018). The article even quoted CICC’s president, Chen Lujun, speaking excitedly about a new co-production with Radio and Television of Portugal (RTP) about porcelain and its impact on globalisation. The collaboration may sound innocent enough; but official Chinese coverage makes it crystal clear that the project with RTP is linked to Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy initiative—the Belt and Road—and that the Portuguese broadcaster has joined China’s ‘Belt and Road Media Cooperation Union’, an alliance of media companies around the world committed to working with China on stories linked to the Belt and Road Initiative (BIFF 2018).

Imagine how different this news might look were I to write Chen’s remarks in Realscreen as a kicker quote with just a bit more context:

We want to act as a bridge between China and Europe,’ said CICC President Chen Lujun, who is also deputy director of the News Bureau of China’s Central Propaganda Department. ‘Porcelain is a symbol of oriental wisdom and we are happy to introduce that to the world.

As China becomes an ever-present player on the global cultural and intellectual stage, we should be mindful of the deeper political context surrounding what Xi Jinping has enticingly called ‘China’s story’ (An 2018). Always dancing around this story is another chronicle, wilfully or neglectfully untold, about how that story has been directed, manufactured, and influenced by a single dominant protagonist, the Chinese Communist Party.