Against Atrophy: Party Organisations in Private Firms

Beginning in 2015, foreign companies operating in China began to notice—some for the first time—the increasing presence of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organisations within the day-to-day activities of their firms. Companies in joint-ventures (JV) with Chinese private firms and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) reported demands to revise the articles of association to give the Party organisation (党组织) legal standing within the JV’s corporate governance structure, while others grew alarmed after Party representatives within the foreign firms demanded input to personnel decisions, including layoffs and promotions.

This development was met with deep scepticism by the foreign business community. In November 2017, the Delegation of German Industry and Commerce issued a statement warning: ‘Should … attempts to influence foreign invested companies continue, it cannot be ruled out that German companies might retreat from the Chinese market or reconsider investment strategies’ (He 2017). Similarly, the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China declared: ‘This development is of great concern to foreign JV partners as it significantly changes the governance of the JV and undermines the authority of the JV Board’ (EU Chamber of Commerce 2017).

Foreign companies need not have feared that they were alone in being targeted: Chinese private firms were similarly coming to grips with a newly-energised Party apparatus demanding increased involvement in enterprise decision-making. As reported by the Asian Corporate Governance Association, between the 2015 and the summer of 2017, more than 180 Chinese companies amended their articles of association to give the Party a formal company role (Allen and Li 2018). In September 2018, the China Securities Regulatory Commission released the Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies, which mandated the establishment of a Party organisation in domestically-listed firms and required that companies provide the ‘necessary conditions’ for Party activities.

Chinese authorities painted this development as wholly benign. One official from the CCP’s Organisation Department stated: ‘Most investors welcome and support the Party organisations to carry out activities inside their enterprises’ (State Council Information Office 2017). The State Council Information Office told Reuters that the Party was ‘widely welcomed within companies’ (Martina 2018). Some Chinese firms seemed to concur. According to a public statement issued by the bike-sharing firm Ofo, which established a Party committee (党委) in 2017: ‘What Ofo has achieved so far is based on the CCP and the government’s policy guidance and support of Internet companies and entrepreneurship, which is beneficial to the healthy development of enterprises’ (Zhang 2017).

Why did the CCP leadership suddenly push for the expansion of Party organisations within the private sector? In this brief essay, I argue that the campaign to enlarge the reach of the CCP into private companies cannot be separated from its much wider campaign to increase the Party’s governance over all institutions under its purview, be they state-owned enterprises, law firms, educational institutions, non-governmental organisations, and even within government bureaucracies. This development, in turn, is closely related to the Party’s decades-long campaign to arrest the organisational atrophy that accompanied the post-Mao economic reforms initiated in the late 1970s. Seen in this light, the expansion of Party organisations within private firms is not a discrete effort to infiltrate the private sector per se, but rather is a manifestation of the CCP’s desire to have insight and input into all economic, civil, and political activity within the country.

Looking Back

To understand the current role of Party organisations, it is helpful to briefly trace their evolution since the 1980s. Crucially, throughout the first decade of the economic reforms, Beijing paid relatively little attention to the CCP as an organisation, a result of the overwhelming focus on boosting economic growth and reestablishing political stability after decades of misrule under Mao Zedong. With the economic reforms introduced in the late 1970s, however, issues pertaining to the quality of Party applicants, the maintenance of a robust and accurate cadre evaluation system, and oversight of the regular participation in Party activities by the existing membership fell by the wayside.

The Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 sent shockwaves through the Party’s leadership, exposing the fragilities of China’s own political system, but also the limits of resiliency for Marxist-Leninist systems around the world. In the wake of this political instability, the CCP turned, with renewed vigour, towards shoring up its basic organisational and ideological underpinnings. Newly-installed CCP General Secretary Jiang Zemin told a group of assembled cadres in late 1989: ‘We must make sure that the leading authority of all party and state organs is in the hands of loyal Marxists’ (Dickson 2003, 35). As a result, private entrepreneurs were banned from joining the CCP in 1989. At the same time, a concerted effort was made to increase the Party’s penetration into educational institutions—a logical move given the prominent role students had played in the demonstrations in Beijing and around China. By 1990, there were only 16,000 university student Party members (down from 23,000 in 1982), but within just five years this number had risen to 70,000 (Dickson 2003, 36).

But reasserting the Party’s control proved difficult, owing to the dynamism and unpredictability introduced by China’s own economic modernisation project. After Deng Xiaoping’s celebrated ‘Southern Tour’ in 1992—and the consequent reinvigoration of the reform agenda after a short-lived conservative retrenchment—the Party’s ability to enforce organisational and ideological discipline was tested as countless cadres and government officials ‘leaped into the sea’ (下海) and entered the burgeoning market economy. During the Mao era, when private businesses had been virtually non-existent and Party members tended to stay in one fixed location, it had been relatively easy for the CCP to ensure that members did not stray from their Party organisations. With Party members now moving about the country in search of new opportunities, the CCP Organisation Department—often likened to the Party’s human resourced department—found it increasingly difficult to keep tabs on these ‘floating’ Party members.

But it was not due to lack of effort. In August 1993, the Organisation Department released the Opinions on Further Strengthening Party Work in Foreign Firms, which mandated that ‘all foreign ventures with more than three full party members should establish party organisations in accordance with the provisions of the party constitution’ (Yan and Huang 2017, 43).That same year, the State Council promulgated the Company Law, which required all companies operating in China—both foreign and domestic—to permit the establishment of a Party organisation ‘to carry out the activities of the Party in accordance with the [CCP] Constitution’, and to provide the ‘necessary conditions’ for said Party organisation’s activities. This was as much a move to shore-up the CCP’s ideological control as it was intended to buttress its organisational foundation, as indicated by a 1993 Organisation Department document that declared the principal function of Party organisations in foreign firms was to ‘educate Chinese employees in the theory of socialism with Chinese characteristics, the Party’s basic line, patriotism and the importance of a collective spirit, and help them to resist the corruption of various decadent ideas’ (Yan and Huang 2017, 44).

These efforts proved largely ineffective, however, and by the turn of the century, the CCP was facing an acute organisational crisis. As Bruce Dickson observed in 2000: ‘Large numbers of party members are abandoning their party responsibilities to pursue economic opportunities. The nonstate sector of the economy is growing so fast that most enterprises do not have party organisations within them, and few new members are being recruited from their workforce’ (Dickson 2000, 4). Jiang Zemin attempted to address some of these concerns by reversing the ban on capitalists joining the Party with his ‘Three Represents Theory’ (三个代表理论), which was formally ratified at the Sixteenth Party Congress in 2002. These efforts aside, the organisational integrity of the CCP continued to deteriorate throughout the 2000s, despite the appearance of several (half-hearted) efforts at ‘Party building’ (党建设) initiated under the leadership of General Secretary Hu Jintao.

Ensuring ‘Comprehensive Coverage’

With the political accession of Xi Jinping in late 2012, however, the issue of the Party’s governance capacity and organisational integrity took on a new importance, especially with regard to the Party’s control over, and integration with, the increasingly globalised and innovating private economy. A campaign to ensure that Party organisations had reached ‘comprehensive coverage’ (全面覆蓋) within private firms was first raised by Xi in March 2012, months before he was installed as General Secretary (Yan and Huang 2017). By 2015, these efforts had borne significant fruit, so much so that fears began to spread within both the foreign business community as well as for domestic entrepreneurs that the presence of Party organisations might turn firms into political, rather than economic, institutions.

While it is certainly possible—indeed likely—that Party organisations will expand in scope to become more actively involved in the day-to-day operations and strategy of companies (reassuring language from Beijing not withstanding), the driving impetus behind the current campaign is not to centrally plan the economy. Rather, it is intended to ensure that CCP members are fulfilling their political obligations, and to fend off the possibility that the private sector becomes independent from, and antagonistic to, the Party-state.

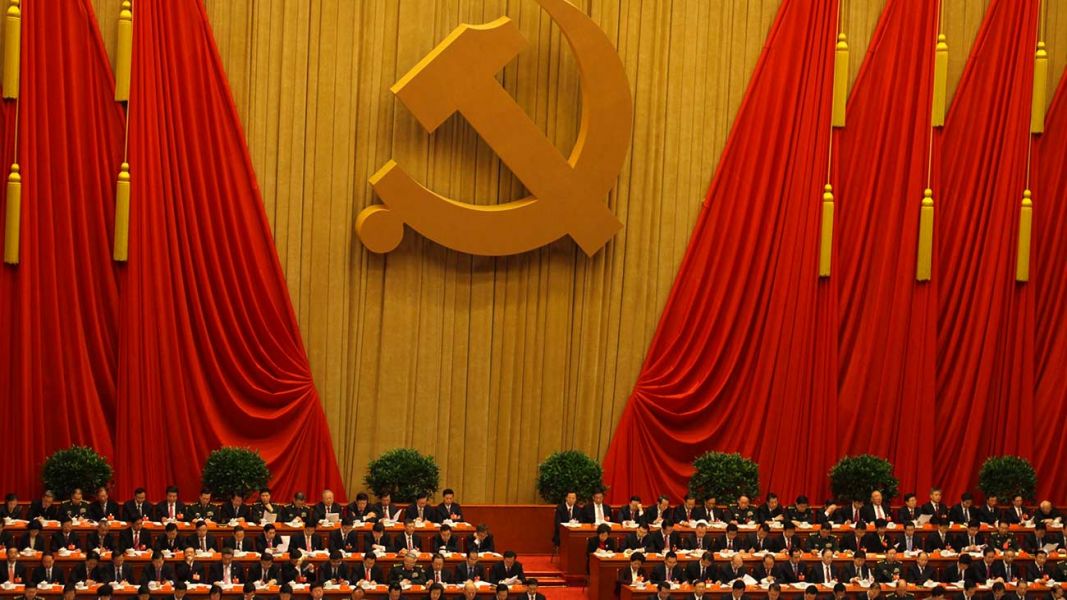

In the end, however, this may be a distinction without a difference. As it struggles to arrest the spread of organisational atrophy, the CCP feels increasingly compelled to insert itself into all corners of civic, economic, and political life. Xi Jinping outlined his vision for the Party in a declaration at the Nineteenth Party Congress in 2017: ‘Government, the military, society, and schools, north, south, east, and west—the Party leads them all.’ Or as one Chinese academic at the Beijing Foreign Studies University put it in more evocative language: ‘The Communist party in China is like God for Christians, and the party committee in a company is like a church’ (Gu 2019).

Embedding Leninist political institutions within China’s private sector will undoubtedly undermine the capacity of the country’s economy to innovate. We should expect strategic decisions within private companies—especially domestic Chinese firms—to become increasingly mindful of the Party’s objectives. Firms in China understand that the CCP is now calling the shots, and the level of political ‘awareness’ by Chinese entrepreneurs must necessarily increase if they are to remain within the bounds of Party-approved activities. Political decisions-making will compete with, and eventually crowd out, economic considerations. So while the Party many eventually achieve ‘comprehensive coverage’ over the private sector, and thus win its war on organisational atrophy, this victory will come at a significant cost for China and the Chinese people.