How Does the Phoenix Achieve Nirvana?

In the spring of 2007, at the first meeting of the Asian Council at the Guggenheim, while introducing his works Chinese artist Xu Bing mentioned Joseph Beuys and Mao Zedong. Beuys is an object of emulation for China’s ‘85’ [1985] new art movement. When Xu first arrived in the United States and heard a recording of a Beuys lecture, he felt an immediate familiarity. For Xu, Beuys’s artistic experiments break the barriers between art and life, aesthetics and politics—and, for him, this is a smaller-scale version of Mao Zedong’s theory on the practice of art and politics. In the artist’s own words, ‘I tell [Westerners] their most important teacher is Beuys and my most important teacher is Mao Tse Tung . . . Mao is actually a big contemporary avant-garde artist’ (Pearlman 2007).

At the centre of Xu Bing’s most famous works, such as Book from the Sky (2016), is the materiality of language and experiments in the relationship between signifier and signified. His use of the form of Chinese characters, and invented characters, has helped break down the national limitations of language and writing. In other works—such as Background Story (initiated in 2004) and Phoenix (since 2008)—he likewise foregrounds materiality to break down barriers. Both of these installations use trash as their artistic material; in Background Story, he arranges junk behind a screen to resemble a Chinese painting when backlit. A Chinese painting and junk: which is the signifier, which is the signified? Here Xu Bing plays on the tensions and porous borders between realism and abstraction, form and object.

Throughout all of his projects, he practices a politics of equality: his art does not represent or address any particular group. Object and spirit, concrete and abstract, the discarded and the cherished, Xu treats all of these dichotomies as barriers to be overcome. That he pays close attention to materiality is natural given to his sensitivity to signification. I suggest that this cultural materialism can only be understood if we place it within Xu Bing’s explorations of the semiotic politics of reproduction. We must also understand Xu’s work within a kind of non-teleological dialectics. The dialectical character of his works is easy to see, but their non-teleological nature is a topic that comes up in examining the politics of his work.

Reconnecting Art and Everyday Life

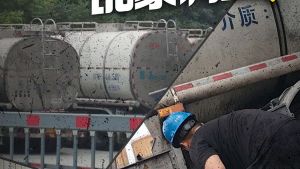

After he returned to China in 2009, Xu Bing created the massive sculpture named Phoenix. The work is composed of junk material and discarded work tools, enacting a return to the site of its assembly by workers. Originally it was to be a red-crowned crane, but the idea was rejected by the investors. There is a message here. When I saw the work while it was being produced, I thought of the 1934 incident of Rivera’s fresco Man at the Crossroads at Rockefeller Center, which was scraped off at the behest of Nelson Rockefeller for including a portrait of Lenin. One can compare Rivera’s homage to communist ideals to Xu Bing’s use of the detritus of capitalism and labour to create a piece to be displayed at a centre of global capitalism. Although Xu Bing’s work is more metaphorical, in neither piece can the form conceal its subversive anti-capitalist character. Was the project initially rejected because of the dissonance between the beautiful form of the phoenix and the material of construction waste? Or because the space of the financial centre cannot accommodate its own excess material? From the perspective of art and politics, this piece embodies Xu’s stance towards inequality in contemporary China and the world, and achieves a unique materialism and formalism within the artist’s corpus of egalitarian artwork.

Phoenix is a continuation of twentieth-century art, but also speaks to a new set of conditions. Under the polarised structure and shadow of the Cold War, the 1960s were an era in which politics entered directly into art, such as in Rivera’s murals of Lenin, Trotsky, and Mao, or in Beuys’s collection of trash leftover after a mass meeting. These works contain a certain irony toward revolution, whereas the revolution promised a different world from the one represented in the artworks, enabling a negative dialectics in which the individual self could come into view. This period also gave birth to a new political relationship between art and life, allowing art to directly participate in politics, but also giving import to new political movements. The politics of form and physicality are exposed in the process. In line with this tradition, Phoenix calls for a political connection between art and everyday life, dismantling the barriers that separate the two. Although Xu Bing’s work has gradually transcended the politics and frame of reference of Beuys and 1960s art, we must therefore use the latter to understand the expression and implications of the work of the Chinese artist.

However, Xu Bing’s work takes place in a post-Cold War era in which global capitalism dominates the world. Revolution, except for its appropriation by the market, can no longer directly sustain the politics of the artwork, having become just a brand of ‘political pop’. The politics of contemporary revolutionary works is one of ‘depoliticisation’ (去政治化, literally ‘expelling politics’), and fulfils the logic of accumulation of the international art market. As revolution has become branded, the bitter history of the spread of capitalism has been transformed into a comedy. This process announces the impossibility of all revolution or any challenge to capitalism. Xu Bing’s art not only rejects all art that takes revolution as a brand, it also resourcefully and tenaciously seeks out a new politics for art. In contrast to political pop and its saturation of the market, his art is markedly nonviolent and apolitical. He focuses on probing form and language, going deeply into the complexity of processes of reproduction, working with great care and precision, as in the meticulously considered and wrought coarseness of his Phoenix: gloves, hardhats, shovels, work clothes, buckets, pliers . . . these tools of labour carry the scars of work, and congeal the time of labour. The value of the commodity is produced in labour time, but labour time can also be evidenced in discarded trash, and the workmanship imprinted in junk. Marxist political economics discovered that abstract labour determines the value of the commodity expressed through labour time. But Xu Bing’s use of discarded junk raises the question of what, exactly, is produced by labour. Production should not be examined only from the standpoint of labour but also in how it relates to capitalist temporalities of unlimited growth, planned obsolescence, and its material form in waste.

Amid the Ruins of Labour

As a product of ruins and modern construction, Phoenix is material junk. Ruins appear continuously in the history of art; from the Romantic School to modernism, we can trace the shifting meaning of ruins and junk, but why should junk become so particularly emblematic in our era? Jia Zhangke’s 2006 movie Still Life exhibits a different kind of ruins, i.e. the remainders of a past world. In the words of poet Xi Chuan, Jia Zhangke’s ruins are discarded villages, but the disappearance of the village also manifests a vital attitude toward the future, making his film neither a tragedy nor a celebration, but rather a chaotic mix of emotions (Li et al. 2007, 7–8). The ruins of the Phoenix have nothing to do with a previous world, as they are not a leftover from the past. Their material is a product of contemporary building projects, connected to the labour of a new generation of workers, and thus the flipside of the financial centre itself. Phoenix uses the excess of production, the discarded part of labour as its material and original design, employing both form and image to produce a richly suggestive piece. With this installation, Xu Bing is attempting to represent an era by archiving the materiality of it.

This motive is closely connected with his reconsideration of artistic tradition, leading to an intriguing exploration of form. Like his earlier work, Phoenix explores the connection between real and artifice; the phoenixes directly touch on the real because they employ the detritus of construction, remnants of labour, and surplus of capital. Through these objects, you can viscerally understand the situation of China in the early twenty-first century. But amidst this realism, Xu Bing also seeks another image related to traditional art, returning to the barrier between life and art that we encountered above. While Beuys produced a political intervention by breaching the barrier, Xu Bing moves in a counter direction through the reestablishment of form which parodies art’s self-commodification. Just like how politics, revolt, and revolution—regardless of political view—can be transformed into brands in order to increase the price of art, the overcoming of barriers between life and art, or art and politics, has become commonplace in the art market. Under these conditions, Xu has restored a sense of form that preserves the distance between art and life, as a commentary and revelation of the state of contemporary life. In a world where labour has been fundamentally de-subjectified (去主体化), the subjectivity of art can reform the depoliticisation of the life world. Therefore, the reconstruction of a barrier between life and art has transformed into the reentry of art into life.

As implied above, Xu Bing’s work captures contemporary politics in a world where the political is everywhere expelled. In such an era, where art treats politics as decoration, so-called political art is even more commoditised than the pure commodity; politics is diluted into questions of rights; and, the line between politics and performance is blurred; all of which suggest the impossibility of politics and the superfluity of politics. Xu Bing’s art is sharply ironic: like Michelangelo who painted religious scenes but infused them with the human world, Xu uses the symbol of the contemporary capitalist world, the financial centre, as a decoration for his artistic installation. However, through preserving the texture and meaning of large-scale junk and making the discarded junk of the financial centre part of the phoenixes’ bodies, Xu has created a scene that is self-deconstructing. The meaning of the junk material is at least twofold: on the one hand, it is the excretion of the shining world of capital and modern architecture, thus showing how capitalism uses material and creates waste in producing its ‘bright world’. This is the logic of capital. Another aspect is the opposite of capital, i.e. labour. Most of the details of the piece gesture to labour and the leftovers of work. This piece thus produces an ironic statement about the relationship between capital and labour under contemporary conditions. All of the details in Phoenix are related to labour. The material of the phoenixes is not only construction junk but creates a different material derived from the combination of the tools, products, and traces of labour. Likewise, it is a product of labour-value. The financial centre and the construction junk stand apposite, complementing each other, but also in contrast to one another. Within this double abandonment, Xu Bing creates a nirvana (涅槃), where, as he put it in conversation, the phoenixes are cruel and vigorous but at night become gentle and beautiful, thus showing the slyness/cunning/slipperiness of capital, and the value of labour.

However, the labour that is preserved in Phoenix is far removed from the tumultuous excitement of revolution. Although Xu Bing felt a familiarity toward Beuys, as well as Mao Zedong’s theory of art, his motives are not as directly political as that of the former and, unlike the latter, does not seek to inspire large-scale mass action, or the idolisation of labour. Rather, it is best to think of Xu Bing as taking the ‘taciturn character’ of contemporary labour and infusing it with an enriching texture. The financial centre is a symbol of financial capitalism. This differs from industrial capitalism: on the face of it, financial capitalism is just the movement of numbers, and has no connection to labour. But, as in the past, the areas where money flows also produce connections between capital and labour, only in this central node of finance capital, the connection between labour and capital is even more ‘flexible’ than under industrial capitalism, to the point that finance can seemingly create accumulation without passing through labour.

The labourers have paid their price for this high-level abstraction of production. At the same time as Xu Bing created Phoenix, the Chinese sphere of labour was further approaching a fatally taciturn form of resistance: the suicides of the workers in the factories of the Taiwanese-owned Foxconn in southern China. With no connection to revolution, without even going on strike, 13 workers, one after another, jumped to their deaths at the factory, ending work by ending their lives. We cannot discern which electric devices are a product of these dead workers’ labour, but these devices are just as handy as other commodities. It goes without saying that this form of struggle is of an entirely different type from the large-scale mass movements of the twentieth century, particularly the 1960s. The abstraction of labour has fundamentally transformed people into living machines, and the cruelty of the process of production has reached an unprecedentedly refined level. Compared with the history of the labour movements of the twentieth century, what we see today can be understood as the voluntary resistance of labour under the conditions of depoliticisation. This is also a form of politics under the conditions of its absence and, in the retreating tide of political labour movements, what is left is a more individual form of political struggle. We can link this historical transformation with Xu Bing’s works to explain the place and meaning of labour in today’s world. Within Phoenix is preserved the body temperature of labour, but at the same time through this temperature we see the place of labour and its condition in today’s world.

Eerie Silences and Enchanting Lights

The phoenixes are silent, and at night they give off an enchanting light. This causes us to reflexively ask of contemporary art: why have some of the deformed symbols of revolution or portraits of revolutionary leaders become logos of international finance? On a larger level, it is because the politicisation of labour is impossible; labour has historically been degraded into a silent and abstract existence. Following the process of globalisation, labour and capital have often been spatially separated, with the result that the politics produced by the proximate confrontation between two has been fundamentally lost. Why have the symbols of revolution and unity between different political views also become a form of commodified exchange? The subjectivity of resistance has disappeared, and all that remains are some substitutes of the politics of times past. Today political struggle and the social terrain have experienced change in a way that raises the question: by what means can we enter into this new politics? Xu Bing has given us the answer of how art can penetrate these new politics. The extraordinarily deep irony of Phoenix has political significance. I think the installation contains both a dialogue with the more traditional politics of the twentieth century, but also vitality within the entirely different conditions of today.

From early on, Xu Bing has explored the question of relations between East and West. Through exploring the relationships between reality and artifice, form and spirit, concreteness and abstraction in the history of art, he has broadened his speculation. His experiments both relate to and surpass twentieth century art. In the twentieth century, literature and art increasingly had to engage in self-dialogue, reconsidering the trajectory of the Self. Unfortunately, for many artists, this sort of dialogue and self-reflection, as well as the attempts to break down barriers, had the opposite consequence: instead of breaking down a closed system and reconstructing the political connection between art and politics, these experiments ultimately transformed art into a completely autonomous entity, no longer able to enter into social life. From this point of view, the meaning of Xu Bing’s work is that it breaks out of this phenomenon: on the one hand, the phoenixes are fictitious (虚拟) images, but on the other hand, the materials they are constructed out of are realist (写实). Though taking a different route, this achieves a similar result as Background Story: the background is discarded junk, the foreground is artwork; it is a reciprocal relationship between signifier and signified.

These relations are dialectical, but they do not refer to a definite objective; it is better to say that their mutual relationship is based on irony. Here when I raise the question of objective, I am not speaking of the general object of criticism, or exposing the loss of such an objective in the process of depoliticisation. The structure of irony and the development of politics are closely related. Politics develops in the relationship between the Self and foe (敌我), such as in the pairing of capital and labour. However, the tension between capital and labour is at the same time structural, e.g. the increase of value in capital has a complementary relationship with the value of labour production. Without labour—or the working class—capitalism cannot be called capitalism. Only when revolution erupts, does a rift occur in this structural relationship, and transform into political resistance. Today the relationship between capital and labour is deeper and broader than ever before, but the oppositional gap between the two only exists on account of the form of the structure. Labour is now silent, and, even if some resistance still exists, it manifests itself in a non-political form. In the atmosphere of today, Phoenix offers an opportunity to think politically about the remnants of labour.

In the summer of 2010, Xu Bing’s Phoenix was exhibited at the Shanghai World Expo. The exhibition hall was not as sumptuous as the financial centre, but rather was an abandoned garage that had been renovated. It is said that among all the magnificent convention halls of the World Expo, only the roof of this abandoned garage was capable of supporting the weight of the phoenixes. During the daytime, the space and the body of the installation both give off an aura of abandonment; only at night, do the mystical lights allow the phoenix to take flight in this place of labour. Not far off is the Lupu bridge, arching over the Huangpu river, even more resplendent than any of the exhibition halls at the World Expo. This is a related message of border-crossing. It is precisely in focussing on this sort of space that, through his artwork and its attendant challenging controversy, Xu Bing becomes a thinker in the art sphere.