Amateur Art Practice and the Everyday in Socialist China

In 1975, the émigré writer and artist Chiang Yee returned to China, the country of his birth. He had inadvertently been away for over four decades, separated from his family by the outbreak of war after leaving for London in 1933. In the years that followed, the possibility of returning seemed vanishingly distant, and Chiang spent decades trying to reconcile with the painful fact that he might never see the wife and four young children he had left behind again. Chiang poured his feelings of loneliness and alienation into writing and painting about his experiences abroad, works that were eventually published as a popular illustrated travelogue series called ‘The Silent Traveller’. Written from the perspective of a self-described ‘homesick Easterner’, many credited Chiang’s best-selling series with making Chinese culture and art accessible to mid-century Anglo-American audiences.

When Richard Nixon made a state visit to Beijing in 1972, suddenly returning to China seemed possible, as restrictions around foreign travel loosened. Chiang was one of many overseas Chinese who were eager to return. Even after four decades away, he still held tightly to his Chinese identity and was keen to reconnect not only with his family, but also with his country of origin. He had watched from a distance as a new state with a utopian vision for the future had been established, one that entailed radical and revolutionary reorganisations of life and society. Chiang ‘was so Anxious and curious to learn about these great changes,’ Chiang applied for a visa in 1974. In April 1975, he finally returned for a two month-long tour of the country after 42 years away.

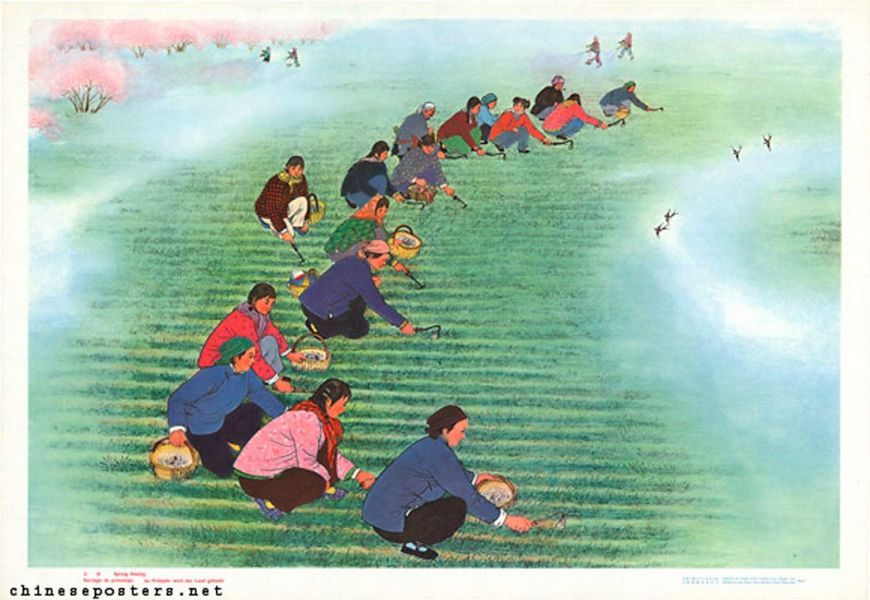

During his trip, Chiang visited Hu Xian, a rural village on the outskirts of Xi’an, Shaanxi province. Hu Xian had become well-known both within and outside the People’s Republic of China (PRC) for the artistic accomplishment of its amateur artists, farmers who in their ‘spare time’ (业余) off from agricultural labour painted colourful and captivating works that depicted life in the countryside1. Although Chiang and the Hu Xian farmers were separated by many things, they shared a common passion for art, and Chiang spent the day getting to know them.

Chiang was impressed by what he saw, and recorded his experience in Hu Xian in an account of his trip. First, the existence of ‘peasant-artists’ in the PRC was in and of itself a revelation, as ‘a peasant who could paint … was unheard of in the past, for in the old days, few of them could have any education, let alone be taught how to handle a brush’ (Chiang 1977, 76–77). But Chiang found their art exceptional too. Their works ‘possessed the gift of rendering their subject matter explicitly with artistic arrangement,’ which Chiang compared favourably to iconic pastoral works in the Western canon, such as Jean-François Millet’s ‘The Gleaners’ and Vincent van Gogh’s ‘The Potato Eaters’ (Chiang 1977, 77). He spent his afternoon in Hu Xian deep in conversation with fellow artists.

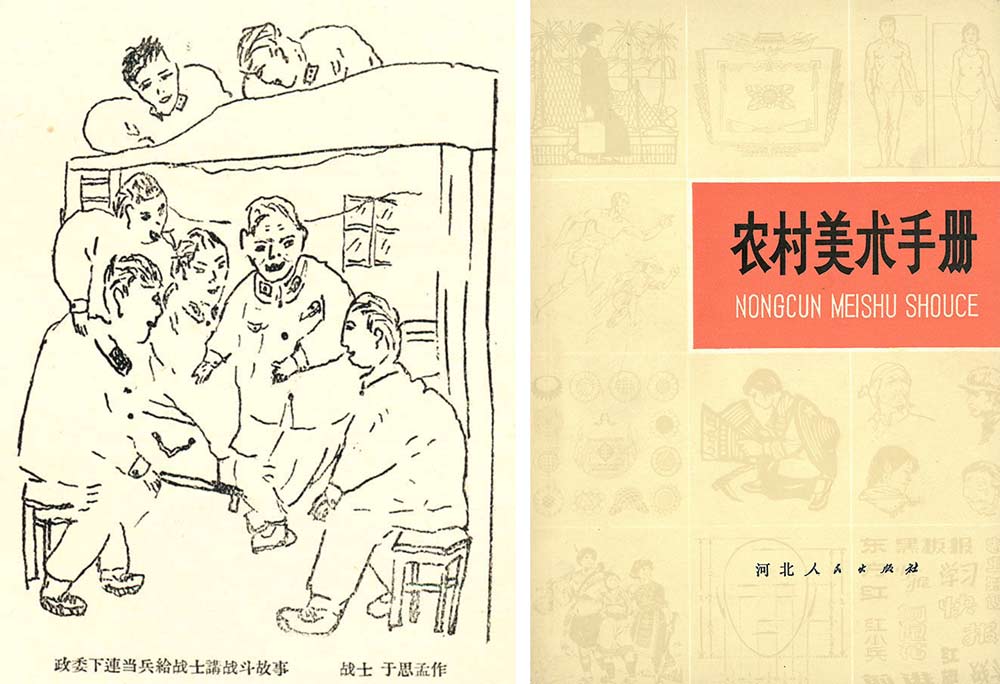

What Chiang witnessed in Hu Xian was perhaps the peak of an artistic practice that had, at that point, been cultivated for decades in the PRC: amateur art practice, known variously as 业余美术创作, 业余美术活动, 工农兵美术, and 农民画. Today, if it is remembered at all, the amateur art movement of the socialist period is conflated simply with peasant art, but in fact amateur art practice was pervasive across the working class in China during the socialist period. Socialist amateur art practice had its roots in pre-1949 political organising and production practices, beginning with the encouragement of workers organised by the Chinese Communist Party to draw sketches and cartoons (漫画) criticising counterproductive work habits or depicting ideal ones.

As more amateurs became involved in making art, the practice shifted from a critique of production methods into a broader socialist cultural praxis. Socialist amateur art practice functioned not only as a means for changing the class and labour relations that had previously been dominant in the fine arts, but also as a strategy for converting the expert and professional cultures of the fine arts into a grassroots practice of the everyday. Borrowing the historian Michael Denning’s concept of the ‘labouring of culture’, I argue that amateur art practice similarly ‘laboured’ the fine arts by locating the arts within the social relations of the labouring masses (工农兵群众). The result was a practice that challenged the authority of the art academy as a legitimising site of training, evacuated the concepts of creative genius and technical accomplishment that had previously been linked with the recognition of an artist, and embraced media and subject matter primarily oriented toward the public, as opposed to the market.

The Labouring of Fine Art

Socialist amateur art practice is typically dated to the year 1958, and understood in the literature as a programme initiated as cultural handmaiden to the economic campaigns of the Great Leap Forward. Ellen Johnston Laing (1985), for example, describes what she calls ‘peasant art’ as a programme to ‘immortalize the positive benefits of the Great Leap and the commune in stories, poems, plays, and pictures,’ while the historian Duan Jingli (2001), also interested primarily in peasant art, dates the earliest peasant art study groups to the year 1956 in two locations: one in Pi county, Jiangsu province, and the other in Shulu, Hebei province. Yet it would be more accurate to think of the economic campaigns of the Great Leap Forward as handmaiden to its cultural programmes; after all, as historian Maurice Meisner points out, when the Great Leap Forward was first announced, it consisted largely of ambitious designs for Maoist cultural change, with its signature economic policies—the formation of the people’s communes (人民公社) and steel production targets—only following later. Archival sources indicate that amateur art had been practiced prior to 1958 in the form of art study groups (业余美术创作组), in which workers belonging to the same work unit formed small groups that met regularly to draw and comment on each others’ work, often under the guidance of an experienced artist.

As social formations, professionalism (专) and amateurism (业余) refer to the division of life into working time and non-working time. The two work in tandem with one another, ‘locked in a symbiotic relationship [mitigating] the divide between work and freedom … The absence of one defines and imbricates the other’ (Zimmerman 1995, 6). During the socialist period in the PRC, the professional/amateur dichotomy also referred to the distinction between a trained and untrained artist, itself essentially a class distinction: art academies were the single most important site of legitimisation for aspiring artists, and they were attended almost exclusively by wealthy urban Chinese. In its attempt to eliminate the barriers to art, socialist amateur art practice took the fine arts out of the academy and centred it at the grassroots level: in the military ranks, in the factory, and in the commune. By changing the scale at which art was produced, amateur art practice transformed the fine arts from the highly-individualised, specialised pursuit of an elite, small, and credentialed community, to a mass activity built up from the bottom level of society.

The May 1954 issue of Fine Arts (美术) , the PRC’s flagship art publication, includes an article entitled ‘Art Creation Activities by Shanghai Workers’ that discusses amateur art groups formed among workers in the Shanghai region. The author, Li Cunsong, notes that following Liberation in 1949, sketching and painting had become popular with workers who had ‘turned over’ (翻身), who recognised it as a powerful tool for articulating their new socialist consciousness and sharing it with others (Li 1954). Furthermore, because ‘workers’ artistic output (工人创作) is derived from production needs,’ their art particularly excelled at identifying undesirable working habits. Li describes a cartoon by one worker that satirised production methods favouring quantity over quality, for example. By drawing attention to problematic production methods, amateur worker art played a vital role in improving the production process.

The number of amateur art groups established skyrocketed in late 1958 in tandem with 下生活 (‘sent down’, or ‘entering life’) policies, which sent trained artists to the countryside and embedded them in worker and farmer communities to ‘learn from life’. Over 30 separate worker, farmer, and soldier art communities rose to fame from the late 1950s to late 1970s for their ongoing amateur art activities, earning coverage in national newspapers including the People’s Daily, People’s Liberation Army Daily, and Guangming Daily, while their artwork was displayed at museums and culture halls (文化馆) across the country. Because amateur art groups had access to very different material resources than urban, professional, and academy-trained artists, artwork made by amateur artists embraced low-cost materials that were easily made and displayed: sketches, cartoons, painting, and ‘wall art’ (壁画), or outdoor murals painted on the sides of homes and local buildings.

A 1958 profile of two rural artists in Fine Arts describes how farmers Zhang Shaonan and Zhang Penqing enrich the surrounding communities with art. Described as broad-shouldered and barefooted, with rough hands and strong legs from working in the fields, in their time away from regular farming responsibilities the two Zhangs frequently travel to neighbouring villages on invitation to create art in situ, drawing on communal blackboards, painting murals on village walls, and designing works of propaganda. Unlike the usual artist, the two Zhangs ‘don’t have the disgraceful framework (臭架子) of the old intellectuals,’ and neither are they self-promoting (Zou 1958). Instead, these two farmers from East village in Zhuji, Zheijiang province, are able to create images that resonate with locals owing to their authenticity as peasants (地地道道的农民) and authoritative first-hand knowledge of rural life.

Creating new socialist art meant creating new socialist artists, and amateur art practice played a significant role in challenging the traditional concept of the artist. Where the artist was typically seen as an urban, male, and educated member of the upper classes, amateur art practice asked for members of the masses to fill the role, challenging the idea that one needed to belong to a certain class or gender to be an artist. During the socialist period, the distinction between professional and amateur increasingly came into question. The ‘red and expert’ initiatives of the late 1950s attempted to resolve the long-standing conflict between mental and manual labour through a democratisation of education and technical expertise (Andreas 2009; Schmalzer 2019). Even the term ‘artist’ was revised: where ‘artist’ was usually variously rendered as 美术家, 艺术家, or 画家, the shared suffix 家, denoting an elevated professional status, was replaced by a new suffix—工作者, or ‘the worker’. Thus, the Artist (美术家) was reclassified as an art worker (美术工作者), signalling ‘the intention to redefine the identity of artists and writers as part of the working class’ and to make cultural work legible as labour, as opposed to an act of creative genius (Geng 2018, 2).

In order to accommodate the amateur artist, who is coded explicitly as a member of the labouring masses, it was necessary to adjust the cultural formation that produced and glorified the artist. Accordingly, concepts of the artist as a creative genius began to shift to accommodate the legitimacy of the amateur. For example, in 1955 the painter and woodcut artist Li Qun criticised the concept of genius (天才) as it relates to the fine arts, writing that genius is not an innate hereditary quality, and that it is not pre-ordained at birth. ‘Does [genius] rely on having a superior physiology (生理)?,’ asks Li. ‘In reality, it’s clear that the existence of genius is inseparable from its cultivation, from limitless loyalty to the people, from scientific working methods, from the ingenuity of labour from the difficulty of hard work, and the relationship with the people’ (Li 1955, 39–40). Genius, Li argued, was not a product of a unique and eccentric mind, but rather a matter of individual devotion to métier, reflecting a view that grew in currency as the 1950s led into the 1960s.

Increasingly, the pre-existing concepts of genius were identified as harmful, a cultural formation that explicitly excluded the masses from being recognised in their own right as creative authors. Technique (技术) emerged as a crucial junction at which trained and untrained artists could meet and conduct exchange. Again, Li Qun questioned the traditional assumptions around what constituted good art in the appraisal of amateur art: ‘The problem is that there are some people who cannot perceive the strengths of even works [by workers, peasants, and soldiers] that are overwhelmingly good … and this obviously involves issues relating to the standards of methodologies (标准的方法) by which we appreciate art’ (Li 1958, 8–9). Li Qun proposed that the typical standards by which art had been evaluated were in need of radical rethinking. ‘The idea of supposed artistry (艺术性) is problematic,’ as it does not account for the ideological message or persuasive power of a work. If ‘the spirit of the content … and the spirit of the times’ are discarded and a work of art is appraised by technical skill alone, ‘then you can only come to a negative conclusion’ (Li 1958, 8–9).

Yet at the same time, the possession of the technical skills necessary to create art, such as line drawing, enlargement, shading, volume, the use of colour, and realistic depiction of anatomy, expression, and likeness—were not seen as the dividing line between professional and amateur artists. For Li Qun, a work was strong not because it depicted its subject with anatomical accuracy and verisimilitude, but because the viewer comes away with a clear sense of the image’s narrative. Taking a sketch by a soldier as example, Li Qun praised the work’s ‘exemplary concept and arrangement’, explaining that even though the work had ‘inaccuracies’, ‘it doesn’t use illustration to explain how life is, but rather generalizes (概括) life with an image’ (Li 1958, 8).

Li Qun and other supporters of amateur art blamed a lack of access to adequate opportunities for training in fine art technique. ‘There are those with conservative thinking who have always felt that workers and peasants lack artistic talent, and that fine art shouldn’t be theatrical or performative, or contain themes that appeal easily to the masses,’ wrote Huang Dingjun, head of the Hubei Province Mass Culture Palace (Huang 1958, 36). Li Fenglan, the Hu Xian farmer and mother of four who went on to become perhaps the most celebrated amateur artist of the period, saw herself as proof positive that the peasants could make art just as well as anyone else. Describing the prejudice she had faced from those with ‘conservative thinking’ who thought her gender and class disqualified her from practicing art, she asserted that: ‘We lower-middle peasants (贫下中农) are entirely capable of learning the skills needed to make art. It’s only necessary to have revolutionary ambitions, to be willing to study diligently, and train hard’ (Li 1974). Li Fenglan understood artistic technique as a modular skill that can be acquired through regular practice, regardless of background or preparation. ‘These basic skills don’t drop down from heaven, and they aren’t endowed at birth. They have to be learned from life, from the masses, and from art practice’ (Li 1974).

The Antidote to Most Chinese Art

The amateur art practice of the socialist period was so closely associated with the Cultural Revolution that its repudiation extends well beyond temporal boundaries of the period. Gradually, the term ‘amateur’ (业余) has disappeared from discussion of art by lower-class labourers, collapsing a widespread national art practice into an exclusively ‘peasant’ practice. This is compounded by the celebrity of the Hu Xian painters, whose work was well-received in international exhibitions held from New York to London and Paris during the 1970s, as well as the consolidation of ‘peasant art’ into the revival of ‘folk art’ during the Reform era. And just as leftists felt betrayed by the Cultural Revolution, so too has that view extended to the history of China’s visual arts. In 1984, the art historian Ellen Johnston Laing argued that a stylistic analysis of the most prominent works by Hu Xian peasant painters revealed that those works had, in fact, been largely executed by professional artists, whose contributions were minimised in the service of a pro-peasant political agenda. Laing concludes that the concept of an autonomous and authentic Hu Xian peasant art was—like so much of the socialist period—a fraud.

Laing’s indictment of peasant art practice remains the defining work of English-language scholarship on the Hu Xian phenomenon, and today even those who visited Hu Xian at the time question the legitimacy of their memories. As a student of Chinese language at the Beijing Languages Institute in the summer of 1975, the art historian Craig Clunas—like Chiang Yee—had the chance to visit Hu Xian, meeting and observing its artists. He memorialised the trip in his diary, writing: ‘This stuff is just the antidote to most Chinese art. When you see what the peasants are actually painting, your faith revives’ (Clunas 1999, 53). Views of the period and the art it produced have changed so much that Clunas now cringes at his earlier assessment: ‘My enthusiasm for this work … was fulsome to the point of embarrassment’ (Clunas 1999, 53).

But ignoring amateur art practice’s legacies—and, more broadly speaking, the cultural legacies of the socialist period—creates a wilfully partial history that impoverishes our understanding of the contemporary. Amateur art practice of the socialist period constituted an ambitious reorientation of fine art practice, transforming it from the specialised labour of elite professionals into a productive everyday practice of the masses. Amateur artists themselves challenged assumptions of gender and class privilege that had previously been coded into the figure of the (urban male) artist, facilitating broad participation in the fine arts that destabilised the cultural precepts that had previously defined the figure of the artist. By cultivating creativity through broad public exposure to art instruction, cultural officials and amateur artists elevated the countryside as a source of experiential authority and weakened the art academy’s position as a legitimising site of training. Excluding amateur art practice from the purview of the contemporary reverses the attempt to locate the fine arts within the social relations of the labouring masses, instead consolidating the primacy of market relations over contemporary art practice.