Can the Creative Subaltern Speak? Dafen Village Painters, Van Gogh, and the Politics of ‘True Art’

In independent documentary filmmaking, migrant workers have been captured through two main, interconnected narratives of oppression and resistance (Florence 2018). The former exposes the unjust, exploitative, degrading, and ultimately destructive condition of those living at the bottom of social and economic hierarchies. The latter recognises their agency, beyond victimisation, identifying the ‘weapons of the weak’ (Scott 2008), and the multiple strategies through which they do not merely survive, but also fight against, and even manage to break through, the oppressive system that crushes and tries to silence their labour—and human—rights.

Within this dual narrative framework, there has been an increased interest in migrant workers’ creative rights in relation to Art as a high-brow, big-money, critically-endorsed global enterprise and art as the creativity of the everyday, both markers of urban modernity and, in the Chinese context, post-socialist cities. In earlier works—such as Dance with Farmworkers (和民工跳舞, directed by Wu Wenguang, 1999) or Whose Utopia? (谁的乌托邦, directed by Cao Fei, 2006)—the critical tension between the alienation resulting from labouring in mass production and the emancipating power of creative practices is explored via encounters between artists and migrant workers. In these encounters, the migrant workers are shown as active participants in creative projects that are, however, fully designed, developed, and owned by the urban artist. Elizabeth Parke describes the migrants’ presence in contemporary Chinese art as a ‘public secret’, i.e. what Michael Taussig refers to as ‘that which is generally known but cannot be articulated’ (Parke 2015, 239).

Something quite different takes place in The Verse of Us (我的诗篇, directed by Qin Xiaoyu and Wu Feiyue, 2015, internationally released as Iron Moon) and China’s Van Goghs (中国梵高, directed by Yu Haibo and Yu Tianqi Kiki, 2016). Focussing respectively on worker-poets (打工诗人) and worker-painters (画工), these documentaries explore the migrant workers’ own artistic creations vis-à-vis endorsement-giving institutions, such as literary circles and art galleries, that assign both cultural and capital value to art.

Both documentaries should be considered as part of translingual (mostly Chinese and English, but also other languages) and transmedia narratives broadly concerned with issues related to subaltern creativity in China. These narratives develop across a multiplicity of channels, e.g., books, literary magazines, news, exhibitions, museums, screenings, performances, photo essays, blogs, and academic research. In the case of The Verse of Us/Iron Moon, the narrative focuses more specifically on dagong (打工) poetry, also referred to as ‘battlers’ poetry, an Australian colloquialism that conveys the connotations of ‘working-for-the-boss’ and ‘underdog’ implied in dagong (van Crevel 2017, 247; see also Sorace’s essay in the present issue). The documentary’s audiovisual story continues offscreen in an anthology of translated poems published a couple of years after the film’s release (Qin and Goodman 2016). The worker-poets presented in the documentary and anthology also participate in local events and publications, intersecting with both grassroots literary movements (such as the Beijing-based Picun Literature Group) and state-sponsored institutions. Academics have also contributed to this narrative: take for example Sun Wanning’s pioneering investigation of migrant workers’ cultural practices (2012 and 2014), Maghiel van Crevel’s research on migrant worker poetry in relation to ownership and translatability (2017 and 2019), and Gong Haoming’s examination of ecopoetics in the dagong poetry (2018).

Similarly concerned with subaltern creativity, another transmedia narrative develops in the context of the contemporary Chinese art scene and has in particular focussed on worker-painters. In this case, the documentary film China’s Van Goghs follows in the footsteps of Winnie Wong’s 2014 book Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade; like the book, it takes place in the heart of Shenzhen’s Dafen village, home of the world’s largest community of copy painters. Framing her analysis in the broader context of global art markets, Wong’s book deconstructs clichés and unpacks assumptions about ‘mindless imitation’ or ‘mechanical techniques’ instead describing these painters’ work as originating ‘from the mind’, and representing ‘freehand’ and ‘unmechanical forms of painterly skills’ (2014, 53). The Dafen painters, Wong contends, ‘understand themselves as both dagong workers and independent artists’ (2014, 56). While Wong’s book places its emphasis on the dynamics of production, reproduction, marketing, and exploitation, the documentary takes an intimate perspective on the painters’ lives and focuses on their personal aspirations.

Both the documentary and the book cross paths with the exhibitions of photojournalist Yu Haibo, the co-director of China’s Van Goghs with his daughter, Yu Tianqi Kiki. Yu Haibo’s photos and his exchanges with Dafen Village’s painters are also included in Wong’s book. In addition, this narrative expands to include journalistic reports, such as Wong’s interview on the Shanghaiist website (Tan 2018) and The New York Times’ story ‘Own Original Chinese Copies of Real Western Art!’ (Bradsher 2005).

The ‘worker-painter’ narrative as portrayed through the Dafen case branches out in yet another direction, namely a narrative that includes the national and local government’s investments in Dafen. Dafen’s painters are proudly celebrated and displayed in the local museum, and ideologically appropriated in the newly launched (in 2018) Dafen International Oil Painting Biennale, which, according to its official website, seeks ‘the promotion of oil paintings with creativity and individuality’ and aims to make ‘Dafen […] a platform for China to understand the world and a window for the world to acknowledge China’. The biennale is ‘[u]nder the national development goals of “the Belt and Road” initiative and the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area,’ and is framed in its familiar China-centred rhetoric:

The cultural brand of Dafen International Oil Painting Biennale, Shenzhen (Dafen Biennale for short) continues to exert its international influence, with Shenzhen, the pioneer city of reform and opening-up, as a foothold, continuously radiating outward, promoting the new trend of cultural industry development with stronger confidence, and setting the standards of artistic creation. (My emphasis)

Albeit with quite different agendas, both the celebratory state-promoted narrative and the more critical transnational narrative seek to recognise, collect, document, and give visibility to Dafen painters. Yet, within these narratives, their creative works remain largely contextualised within, and entrapped by, their condition of localised migrant workers.

To Be or Not to Be a ‘True Artist’?

Despite the plural in its title, China’s Van Goghs is mostly centred on one painter, Zhao Xiaoyong. As Wong writes, ‘[a] photogenic and generous man, Zhao has been asked by many foreign journalists, television reporters, artists, and at least one art historian, to appear on camera’ (2014, 155). There is no doubt that, compared to his fellow painters, Zhao has had significant media exposure. His studio in Dafen Village still carries visible and tangible evidence of this exposure on its window, covered with posters of the documentary and the photo exhibitions that have taken his story to international audiences.

The documentary focuses on Zhao’s journey from Shenzhen to Amsterdam and back, as he seeks recognition for the value of his work, not just financially, but artistically. On the official movie website, his story is described as ‘[a]n intimate portrait of a peasant-turned-oil painter who is transitioning from making copies of van Gogh’s paintings to creating his own authentic work of art, emblematic of the journey that China is going through, from “Made in China” to “Created in China”’ (my emphasis). Echoing the documentary’s promotional summary, media coverage also emphasises the empowering, transformative journey towards becoming a ‘true artist’. For instance, on Al Jazeera’s Witness (2018), an article summarises the documentary as ‘Vincent van Gogh’s iconic painting and once in a lifetime trip transform a Chinese painter into a true artist’ (my emphasis). Similarly, in the Hollywood Reporter, the reviewer refers to ‘[a] profound portrait of a struggling artist’ and notes that ‘[v]eering sharply away from the stereotype of Chinese laborers as a faceless mass seeking a better quality of life, China’s Van Goghs explores their desire for spiritual fulfillment, too. […] the filmmakers show their protagonists as bona fide artists, struggling like Van Gogh to find their creative voices and realize their vision beyond their own economic and social circumstances’ (Tsui 2017).

The only departure from the image of a struggling artist or peasant-turned-oil painter is found on the Ueberformat Art website (Conscious Art Consulting). The site is run by San Francisco-based Thomas Kohler (‘partner, guardian, and cheerleader for creatives’) and it describes Zhao as ‘a professional painter’ rather than a labourer with a dream. Both his connection with the Dafen village and the documentary are mentioned, but they are not the main focus of his biographical notes. While Ueberformat’s endorsement suggests that Zhao is a ‘true artist’, the limited recognition of this small online platform arguably only provides additional virtual exposure rather than a functional channel for him to reach out to global markets.

Do Money and Media Make a ‘True’ Artist?

Out of these interconnected media stories, Zhao emerges as a hard-working, wilful but still overpowered migrant worker, seeking, but not succeeding, to be accepted as an independent artist. In contrast, on Chinese media, news coverage about another one of ‘China’s Van Goghs’ suggests that such acceptance is possible. Xiong Qinghua is an example of a story with a happy ending, in which the creative subaltern, after years of suffering, is finally rewarded. In local and national news, Xiong is described as a Chinese Picasso who just wants to be himself (Luo 2017). He is depicted as an underestimated ‘peasant Van Gogh’, initially ‘turned down by Shenzhen’s Dafen Oil Painting Village’, who later managed to gain visibility online and sold ‘many paintings’ by exhibiting in Beijing’s renowned 798 Art District (China Daily 2016).

Xiong’s recognition as an artist is achieved within China, rather than via international approval. One of the unspoken obstacles in achieving such success and recognition may therefore be Zhao’s inescapable—in fact, unchosen—association with Western academia and independent filmmaking, which has given him international exposure, but has also framed him within their critique of both China’s and global capitalism’s inequities, thus possibly making his story less appealing to state-controlled media and/or state-promoted exhibitions.

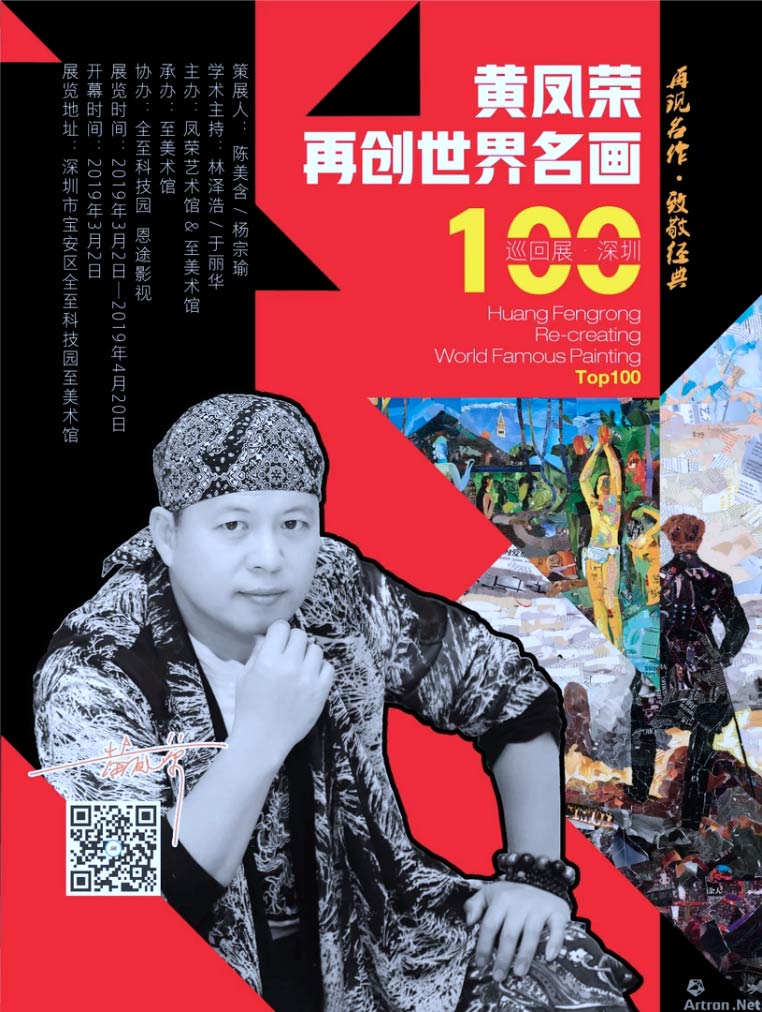

In fact, despite his international exposure, apart from the posters on his windows, Zhao’s studio does not stand apart from those of other fellow painters in Dafen village. Besides the Art Museum, the only other place in Dafen village that catches the visitor’s attention is Huang Fengrong’s stand-alone colourful building, with a door humorously surmounted by the sign ‘1+1=3’.

Huang is a performance painter, native of Putian, Fujian province, who has lived in Shenzhen since 2006. As noted in one of his promotional videos, Huang’s goal is ‘to convey happiness’ and ‘to release positive energy in the form of innovative art’. His histrionic personality and eclectic talent have made him a small celebrity on national media, especially since his participation in the 2010 CCTV Spring Festival Gala. Like in Xiong’s case, on Chinese media, Huang is presented as mostly a home-grown and home-based talent. Reference to his international reach is always framed as a consequence of the recognition he has first obtained in China. Most recently, he completed a multimedia project involving China’s 56 ethnic minorities, which he describes as a journey to experience minority cultures and create works reflecting their attributes. His paintings and the resulting documentary, Impressions of China 56 (印象中国56, 2017), received, once again, national news coverage (Ye 2019). Huang’s online presence also includes his profile on ‘Art Express’—the news section of the China-based, Chinese-language website Artron, where his works and events are listed.

In Huang’s case, recognition appears to result mostly from mainstream validation channels in popular culture and entertainment. On Huang’s YouTube channel, one can find a selection of his painting performances on national television in China, as well as abroad (i.e., his performance at the European Illusion Festival or with Sophie Marceau at the 2016 International Women’s Day). While still lacking recognition in the global Art scene, he attracted the interest of several local universities. For instance, he was an artist-in-residence at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in Shenzhen in 2017 and was invited as a guest lecturer at Putian University in Fujian in 2018. Today Huang appears to have made it; his residence in Dafen is a sort of a pied-à-terre; he travels frequently, but when he is there, he is happy to talk with visitors, take photos, and share his latest news.

Making It Globally: Is the ‘True’ Artist an Educated Urbanite?

With very limited exceptions—such as Xiong Qinghua and Huang Fengrong—in the broader transmedia narrative centred on the worker-painters developed across national and ideological divides, the only prominent named protagonists are actually China and Van Gogh. Van Gogh appears like an obvious, attention-catching device for titles in books, films, and news articles. Not only are the copies of his paintings among those in highest demand and enjoying great popularity both in China and abroad, but he has also come to embody the marginalised, unappreciated genius destined to a life of struggle. However, the recurrent deployment of Van Gogh has also become an effective branding that makes the creative subaltern a valuable ideological and commercial asset, while at the same time it denies them a name, i.e., the key marker of the ‘true artist’. In both domestic and international narratives, with the unintentional complicity of academics, filmmakers, and journalists, the recurrent reference to Van Gogh also functions as a problematic branding that stereotypes, anonymises, and indeed discounts the worker-painters’ own individual creativity.

Such branding contrasts with how Zeng Fanzhi, one of China’s top-selling artists, can in fact appropriate Van Gogh as part of his own creative work (Perlez 2016). As an educated urbanite, Zeng can express his creative agency both through his art and his own voice. In an interview on the occasion of his latest exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in 2017–18, Zeng confidently discusses both Van Gogh’s aesthetics and legend, as an equal: ‘I think our styles are drastically different. We live in different eras and are rooted in different cultures. It is natural for our respective art to take different paths. Van Gogh’s inspiration to me is largely spiritual; in practical terms, it should be easy for the audience to identify our differences from our artworks’ (Gagosian Quarterly 2018). Rather than being absorbed and defined by his association with Van Gogh or within China’s post-socialist dream, Zeng’s established status as ‘true artist’ allows him to be inspired by Van Gogh and be critical of China; most crucially he can be recognised separately and independently from both.

Subaltern Creativity: Exclusion and Oppression in the ‘Cool’ City

By and large, worker-painters have remained excluded by global art circles, as well as the industry’s cash flow and its critical appraisals. Dafen village’s domestic and global visibility has generated both touristic appeal and government interest as a business model for urban development, but it has not given the worker-painters their desired recognition as independent artists. While not deprived of individual agency and arguably able to exert control over their own labour, commissions, and creative work, they are denied both ‘artistic recognition and cultural citizenship’ (Wong 2014, 10).

On the one hand, their collective experience is appropriated in the rhetoric of the China Dream in which ‘socialist values are used to champion the creativity of the nonelite’ (Wong 2016, 212). Unlike Chinese contemporary artists who are ‘setting auction records and exhibiting in art museums all around the world’ (Wong 2016, 193), they remain inescapably defined by and confined in Dafen—‘a dystopian object of the Chinese copy’ and ‘a utopian subject of universal creativity’ (Wong 2014, 10).

On the other hand, as migrant workers, arguably living as permanent outsiders within the city, Dafen painters also face another, possibly even greater, obstacle in their demand for cultural citizenship. Rural migrants have exponentially grown in numbers in the cities, but are still largely marginalised by the educated urbanite middle-class. For China Van Goghs’s worker-painters, just as for Iron Moon’s worker-poets, and more broadly for the creative subaltern, the measure of their artistic recognition may have in fact less to do with the thorny question of what ‘true art’ is and the complex social power relations that determine its answer in any specific time and place. Rather, their lack of affirmation may be mostly predicated on their exclusion from the city’s cultural space.

A key issue here is ‘the alignment of creativity with the cool, sophisticated and metropolitan’, which means that ‘the value of creativity often remains tethered to its capacity to make profits and conforms to the entrepreneurial imperatives of city managers, reinforcing the strategic role of creative industries in economic development and urban renewal’ (Edensor and Millington 2018). Migrant workers who are and want to be recognised as painters and poets clearly show that ‘creativity proliferates and seethes in everyday life and in quotidian spaces’ and ‘cannot only be associated with entrepreneurs and artists’, and should be recognised as ‘undoubtedly located in settings that are far from urban centres’ (Edensor and Millington 2018). Yet, paradoxically, their artistic recognition depends on their association with entrepreneurs and artists in the heart of urban centres.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s famous question—‘can the subaltern speak?’ (Spivak 1994)—underscores Chinese migrant workers’ creative rights and their failure to be recognised as independent artists. It is important to acknowledge that beyond the specificity of the Chinese nation state, Dafen painters’ exclusion and oppression is ultimately rooted in class, social, and cultural hierarchies that have only been exacerbated by global capitalism. In this context, state and local government officials, national and international entrepreneurs, as well as filmmakers, journalists, and academics are all speaking for the subaltern, contributing in different ways and with different goals, to giving visibility to the subaltern’s creativity, but also controlling meaning and assigning value.