Syllabus: Chinese Labour

This syllabus explores the world of Chinese labour in five modules. The first module attempts a genealogy of labour in China through an excavation of key political concepts that were at the core of the discourse of the Chinese Communist Party in the Maoist years and that still have significant reverberations in the post-reform era. The second shifts attention to the reality of labour in today’s China, with a particular focus on those who work at the margins, including migrant workers, laid-off workers, sanitation workers, and slaves in illegal brick kilns. The third accounts for how Chinese workers cope with the hardships they experience, with a particular focus on the role of the legal system in fostering both quiescence and resistance among Chinese workers, and on the shifting dynamics of worker unrest in China. The fourth deals with labour organising in both its top-down component through the activities of the official All-China Federation of Trade Unions and at the grassroots via the work of labour NGOs, feminist groups, and Marxist activists. As the situation for labour activism in China has immeasurably worsened under Xi Jinping, these essays unavoidably focus on repression, but the module also includes discussions about the possibility of campaigning for universal basic income in China and the role of trade unions in the recent wave of unrest in Hong Kong. Finally, the fifth module attempts to divine the future of labour in China between bullshit jobs, overtime fetishisation, robotisation, platform economies, and workplace surveillance.

Course Modules:

- Maoist Roots

- Working at the Margins

- Between Acquiescence and Resistance

- Labour Organising

- The Future of Labour

Module 1: Maoist Roots

- Alessandro Russo. 2019. ‘Class Struggle.’ In Afterlives of Chinese Communism, edited by Christian Sorace, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubere, 29–35. Canberra, London, and New York: ANU Press and Verso Books.

The concept of ‘class struggle’ was one of the principal paradoxes of the Cultural Revolution. As a slogan, it was unfailingly spoken and printed at every turn of that tumultuous decade in China; yet, any attempt to examine those events in the light of ‘classes in conflict’ encounters insurmountable aporia. No less complicated is the problem of how to assess the role of ‘classist’ categories in the Chinese government’s official discourse today, as the Chinese Communist Party keeps reiterating its hallowed role as ‘the vanguard of the working class’.

- Wang Ban. 2019. ‘Dignity of Labour.’ In Afterlives of Chinese Communism, edited by Christian Sorace, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubere, 73–76. Canberra, London, and New York: ANU Press and Verso Books.

In socialist China, working people did not view their jobs as merely a means of making a living. A job meant an honourable vocation, and workers were endowed with dignity. In the 1920s, socialist thinkers Li Dazhao and Cai Yuanpei proclaimed that labour was sacred, because the working class would take control of their destiny in forging a society free from exploitation and oppression. But a look at the working conditions in China today will convince anyone that labour has fallen from grace to become a curse and a nightmare.

- Covell Meyskens. 2019. ‘Labour.’ In Afterlives of Chinese Communism, edited by Christian Sorace, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubere, 103–109. Canberra, London, and New York: ANU Press and Verso Books.

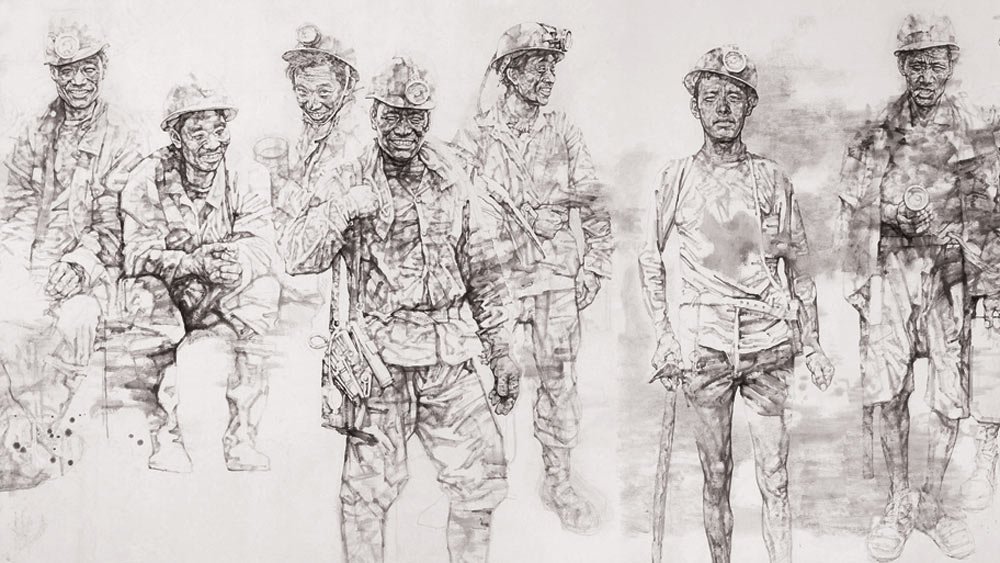

Images of work were a key genre in Maoist visual culture. There were images of people smiling as they worked to build an industrial base for socialist China, but also of people whose countenance expressed total absorption in work by either focussing completely on the object they were producing or staring intently at their colleagues during meetings or training sessions. In these photos, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was often not immediately visible—Party members did not wear clothing that distinguished them from ordinary people—but its ‘spirit’ (dangxing) was present in the gaze of the workers and energy transmitted through their gestures.

- Kevin Lin. 2019. ‘Work Unit.’ In Afterlives of Chinese Communism, edited by Christian Sorace, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubere, 331–34. Canberra, London, and New York: ANU Press and Verso Books.

The work unit (danwei) was the quintessential urban institution of Chinese state socialism. For the generations living through the 1950s to the 1970s, the work unit was much more than simply a workplace. Most aspects of people’s lives were deeply embedded in, and intimately connected to, a danwei, which structured not only their work, but also their benefits, housing, movement, and often their behaviour and thoughts. For many of them, the structural reform and closure of the work units in the 1980s and 1990s proved to be a traumatic experience, upending not only the certainties associated with lifelong employment and guaranteed incomes—the so-called ‘iron rice bowl’—but in many cases also tearing apart the social fabric of their entire communities.

- Ivan Franceschini. 2020. ‘Disenfranchised: A Conversation with Joel Andreas.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 5, no. 1: 188–91.

Work units and the ‘cradle-to-grave’ employment model that they represented have not escaped the general rejection of China’s Maoist past. Not only have they become symbols of inefficiency, but they have also been criticised for putting workers in a position of total dependence and therefore subjugation. In Disenfranchised: The Rise and Fall of Industrial Citizenship in China (Oxford University Press 2019), Joel Andreas attempts to set the record straight by tracing the changing political status of workers inside Chinese factories from 1949 to the present.

Module 2: Working at the Margins

- Francesca Coin. 2017. ‘A Genealogy of Precarity and Its Ambivalence.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 4: 22–25.

Focussing on the conceptual evolution of precarious labour over the past three decades, this essay provides a genealogy of the notion of precarity. On the eve of the fourth industrial revolution, when precarity has become the norm and fears of a jobless society have alimented a dystopian imaginary for the future, this historical reconstruction seeks to identify those elements that have shaped the material conditions of workers as well as influenced their capacity of endurance in times of growing uncertainty.

- William Hurst. 2016. ‘The Chinese Working Class: Made, Unmade, in Itself, for Itself, or None of the Above?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 1, no. 3: 11–14.

China’s working class has undergone several rounds of momentous and wrenching change over the past hundred years. But what has this all meant for interest intermediation or politi-cal representation for labour in China? In order to address these questions, we must accept and understand the fractured and segmented history of the Chinese working class, as well as its rapidly homogenising present. We must also refrain from too-facile comparisons with European or other post-socialist or developing countries

- Chris Smith and Pun Ngai. 2017. ‘Class and Precarity in China: A Contested Relationship.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 4: 32–35.

The increasing precariousness of labour forces globally has prompted some to argue that a new ‘precariat’ is emerging to challenge the privileges of the securely employed ‘salariat’. This divergence within the working class has been depicted as more significant than the traditional conflict between labour and capital. This essay examines these discussions in China, where precarity is increasingly being employed as a theoretical tool to explain the fragmentation of labour in the country.

- Roberta Zavoretti. 2017. ‘Making Class and Place in Contemporary China.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 1: 16–19.

Rural-to-urban migrants in China are often depicted as being poor, uncivilised, and having a lower level of ‘human quality’ than those with urban household registration. Policy-makers carefully strategise in order to produce rural-to-urban migrants as a homogeneous category. However, the use of this term obscures more than it illuminates, as it homogenises complex social realities.

- Kaxton Siu. 2017. ‘From Dormitory System to Conciliatory Despotism: Changing Labour Regimes in Chinese Factories.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 4: 36–39.

China’s manufacturing model has been built on the exploitation of migrant workers under a despotic labour regime. But is that still the case? Based on extensive research in the Chinese garment sector, this essay argues that while draconian controls persist up to this day, the situation of China’s migrants has undergone dramatic transformations that encompass not only changes in the workers’ demographic profile and everyday life practices, but also new social, technical, and gendered divisions of labour inside factories.

- Beatriz Carrillo Garcia. 2016. ‘Migrant Labour and the Sustainability of China’s Welfare System.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 1, no. 4: 15–18.

Social welfare in China has emerged as a major cause of migrant workers’ discontent. Reforms of the social welfare system in China since 2002 have expanded coverage and protection of vulnerable populations, but structural problems remain for migrant workers to access and receive the full benefits of the social safety net. How has the social welfare system evolved, and what are the challenges facing migrant workers? How can the system be made more sustainable?

- Yu Chunsen. 2018. ‘Gongyou, the New Dangerous Class in China?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 36–39.

For decades, labour scholars have been debating the transformation of the identity of Chinese migrants from ‘peasants’ to ‘workers’ in an attempt to assess the extent of their class consciousness. This essay examines a new identity—framed as ‘gongyou’, or ‘workmate’—that is developing among the new generation of migrant workers in China.

- Thomas Sætre Jakobsen. 2019. ‘Beyond Proletarianisation: The Everyday Politics of Chinese Migrant Labour.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 52–57.

In China as elsewhere, labour studies typically focus on visibility, organisation, and collective endeavours taken on by workers and their organisations to improve the collective situation of the labouring class as a whole. The privileged site for these overt manifestations of labour movement politics remains focussed on urban areas in general, and on manufacturing work in particular. This essay argues that this view is reductive, in that it only takes migrant labourers seriously as political actors once they enter the urban workplace. This risks neglecting the reality of hundreds of millions of workers who live between the farmlands in the countryside and the workplaces of the city.

- Nellie Chu. 2018. ‘Reconfiguring Supply Chains: Transregional Infrastructure and Informal Manufacturing in Southern China.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 40–45.

In recent years, rising labour costs and unstable market conditions in coastal areas have prompted former migrant workers and small-scale entrepreneurs to move their manufacturing activities to interior provinces. While this has been made possible by China’s infrastructural upgrade, this essay shows how infrastructure projects that link China’s interior and coastal manufacturing regions have ended up intensifying key aspects of the country’s informal economy.

- Kevin Lin. 2018. ‘Eviction and the Right to the City.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 1: 15–17; Qiaochu Li, Song Jiani, and Shuchi Zhang. 2018. ‘Beijing Evictions: A Winter’s Tale.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 1: 28–33.

In response to a deadly fire in a Beijing neighbourhood inhabited mostly by migrant workers, in November 2017 the authorities of the Chinese capital launched an unprecedented wave of evictions. Without any notice, migrants who often had spent years in the capital were told to leave their habitations and relocate elsewhere in the midst of the freezing north-China winter. These two essays look into how Chinese civil society responded to the crisis and examine the broader implication of the evictions for the right to the city of Chinese migrant workers.

- Dorothy Solinger. 2017. ‘The Precarity of Layoffs and State Compensation: The Minimum Livelihood Guarantee.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 1: 40–43.

When discussing the outcomes of China’s economic development, the poverty that can still be found in Chinese cities is seldom mentioned. While the Party-state is indeed making a token effort to sustain the victims of this destitution, these people and their offspring will never be able to escape this manufactured poverty. This essay looks at the policy process that led to this outcome and at the prospects for poverty alleviation in Chinese urban areas.

- Robert Walker and Jane Millar. 2020. ‘Is the Sky Falling in on Women in China?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 5, no. 1: 50–55.

China has fallen to 106th place in World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Index for 2020. Drawing on recently-published research by Chinese scholars, this article explores whether this accurately reflects the status of women in contemporary China, concluding that China’s progress towards gender equality has stalled in the face of the powerful combination of marketisation and patriarchy.

- Amy Zhang. 2019. ‘Invisible Labouring Bodies: Waste Work as Infrastructure in China.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 4, no. 2: 98–102; Adam Liebman and Goeun Lee. 2020. ‘Garbage as Value and Sorting as Labour in China’s New Waste Policy.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 5, no. 1: 56–63.

These two essays look into the latest development in China’s waste management policies from the lens of the labour involved. Zhang’s article examines the failure of China’s attempts to implement citizen recycling programmes and argues that, in the absence of citizen participation, recycling, and waste collection are nevertheless achieved by workers who mobilise their labour, constituting a mundane, low-tech infrastructure to recuperate and circulate waste. Liebman and Lee focus on the controversial new garbage sorting system adopted in 2019 in Shanghai. By considering often-unrecognised forms of labour and the interstices of value that many waste objects occupy, they examine how waste work has become a site of heightened contestation with multiple types of value in play.

- Ivan Franceschini. 2017. ‘Slaving Away: The “Black Brick Kilns Scandal” Ten Years On.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 2: 16–21.

In the spring and summer of 2007, bands of aggrieved parents roamed the Chinese countryside looking for their missing children, whom they learned had been kidnapped and sold as slaves to illegal kilns. Thanks to the involvement of Chinese media and civil society, the so-called ‘black brick kilns incident’ became one of the most remarkable stories of popular mobilisation and resistance in contemporary China. Now that ten years have passed, are there any lessons that we can draw from this moment in history?

Module 3: Between Acquiescence and Resistance

- Elaine Sio-Ieng Hui. 2016. ‘The Neglected Side of the Coin: Legal Hegemony, Class Consciousness, and Labour Politics in China.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 1, no. 3: 11–14; Ivan Franceschini. 2018. ‘Hegemonic Transformation: A Conversation with Elaine Sio-Ieng Hui.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 82–87.

Discussions of Chinese labour are generally dominated by stories of exploitation. Relatively little attention has been paid to the fact that over the past two decades the Chinese authorities have developed an impressive body of labour laws and regulations. There has been even less notice of the fact that this legislation was widely disseminated among the Chinese public through the official media, or of how these laws have regularly elicited widespread domestic discussion. But how to reconcile these notable legislative achievements with the global image of a government that apparently does not care for the wellbeing of its workers?

- Aaron Halegua. 2016. ‘Chinese Workers and the Legal System: Bridging the Gap in Representation.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 1, no. 3: 15–18.

A decade ago, the Chinese authorities adopted a set of new laws to grant increased legal protections to workers and easier access to the legal system to enforce their rights through litigation. Since then, Chinese workers have increasingly turned to labour arbitration and courts in the hope of resolving their grievances. But how do they fare in this process? And are they able to find legal representation?

- Ivan Franceschini. 2016. ‘Chinese Workers and the Law: Misplaced Trust?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 1, no. 2: 16–19.

In recent years, much has been written about the ‘rights awakening’ of Chinese workers. But what kind of rights are we talking about? Do they respond to an entirely subjective concept of justice or do they somehow coincide with the entitlements provided by the labour legislation? On the basis of a survey carried out among 1,379 employees of Italian metal mechanic companies in China, this article will attempt to answer three key questions: how do Chinese workers perceive the labour contract? How much do they know about labour legislation and how does this knowledge affect their trust of the law? What do they think about going on strike as a strategy to protect their rights?

- Chris King-chi Chan. 2018. ‘Changes and Continuity: Four Decades of Industrial Relations in China.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 24–27.

China’s economic reforms started exactly forty years ago. Labour scholars today are debating the extent to which labour relations and the labour movement in China have changed, and where they may be heading. Positions are polarised between pessimists who emphasise the structural power of the market and the authoritarian state, and optimists who envision the rise of a strong and independent labour movement in China. This essay advocates for a different approach.

- Manfred Elfstrom. 2017. ‘Counting Contention.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 4: 16–19.

In the past few years, a growing number of academics and activists have launched projects aimed at counting contention in the realm of Chinese labour. This essay explores the power and limitations of such efforts, detailing the inevitable data problems involved in any quantitative approach to documenting protests in China. It also examines the ethics involved in how we collect such data and the questions we ask of it.

- Geoffrey Crothall. 2018. ‘China’s Labour Movement in Transition.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 28–35.

In the first five years of Xi Jinping’s rule, China was characterised by slowing economic growth, the decline of traditional industries, a rapid growth in service industries, and the increasing use of flexible or precarious labour. This has had a clear impact on Chinese workers. This essay illustrates the latest trends in labour activism in China, examining the workers’ main demands, the types of protest, the number of participants, and the responses of the local authorities and police.

- Zhang Lu. 2018. ‘The Struggles of Temporary Agency Workers in Xi’s China.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 46–49.

In China, temporary agency workers often receive as little as half the pay and none of the benefits enjoyed by their ‘regular’ counterparts, which has resulted in high-profile struggles across sectors. This essay examines their recent collective actions in the automotive industry, pointing to the challenges and potentials for future labour activism in contemporary China.

- Ma Tian. 2017. ‘Migrants, Mass Arrest, and Resistance in Contemporary China.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 4: 12–14.

In today’s China, migrant workers are commonly perceived as criminals. This essay examines how this bias is reflected in mechanisms of crime control, as well as in the judicial and correctional systems. It also looks into the strategies adopted by migrants to cope with this kind of discrimination by the law enforcement bodies.

Module 4: Labour Organising

- Ivan Franceschini. 2019. ‘Trade Union.’ In Afterlives of Chinese Communism, edited by Christian Sorace, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubere, 293–301. Canberra, London, and New York: ANU Press and Verso Books.

Through the voices of union and Party leaders of times past, this essay discusses the role of the trade union in China and shows how, beyond the apparently smooth surface of orthodoxy, the relationship between the CCP and ACFTU has often been marred by seething tensions, ready to explode at critical economic and political junctures.

- Geoffrey Crothall. 2020. ‘Trade Union Reform in China: An Assessment.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 5, no. 1: 19–23

When Xi Jinping formally launched China’s trade union reform initiative in November 2015, it was not exactly headline news. However, what China’s trade unions do and, just as importantly, do not do can have a tremendous socioeconomic and political impact. If carried out effectively, the trade union reform initiative has the potential to benefit not just China’s workers but also bolster the political legitimacy of the Communist Party—hence the push from the very top of the Party.

- Katie Quan. 2017. ‘Prospects for US–China Union Relations in the Era of Xi and Trump.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 3: 48–53.

Under the presidency of Xi Jinping and Donald Trump, relations between trade unions in the United States and China have come to a virtual standstill. To understand how we arrived at this point, and what can be done to break the impasse, this essay briefly reviews the historical development of union relations between the two countries. In order to achieve this, it draws on voices of those labour leaders in the United States who have been direct participants in efforts to develop early contacts with their Chinese counterparts.

- Ivan Franceschini. 2016. ‘Revisiting Chinese Labour NGOs: Some Grounds for Hope?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 1, no. 1: 16–20; Ivan Franceschini and Kevin Lin. 2018. ‘A “Pessoptimistic” View of Chinese Labour NGOs.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 56–59.

In the wake of the 2015 crackdown on labour NGOs, pessimism about the future of Chinese civil society has been unavoidable even for the most assured optimists. Still, pessimism and optimism in discussions of Chinese labour NGOs have roots that go far deeper than these latest turn of events. These essays take stock of the situation and reconsider the debate in light of the latest developments, proposing a possible synthesis between ‘optimistic’ and ‘pessimistic’ views.

- Zeng Jinyan. 2018. ‘We the Workers: A Conversation with Huang Wenhai.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 66–75.

Shot over a six-year period (2009–15) mainly in the industrial heartland of south China—a major hub in the global supply chain—the 2017 film We the Workers follows labour activists as they find common grounds with workers, helping them to negotiate with local officials and factory owners over wages and working conditions. Threats, attacks, detention, and boredom become part of their daily lives as they struggle to strengthen worker solidarity in the face of threats and pressures from police and their employers. In the process, we see in their words and actions the emergence of a nascent working-class consciousness and labour movement in China.

- Eli Friedman. 2017. ‘Collective Bargaining in China Is Dead: The Situation Is Excellent.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 1: 12–15’ ; Kevin Lin. 2017. ‘Collective Bargaining or Universal Basic Income: Which Way Forward for Chinese Workers?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 3: 16–19.

As the Chinese government under Xi Jinping turned in a markedly anti-worker direction, attempts to establish a genuine collective bargaining system in China were been smothered. If collective bargaining is dead, what might Chinese workers and their allies advocate? These essays discuss whether time might be ripe to shift the focus to a demand for a rapid expansion of universal social services, not least for a universal basic income.

- Dong Yige. 2019. ‘Does China Have a Feminist Movement from the Left?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 4, no. 1: 58–63.

While most international media have applauded the latest waves of feminist activism in China, some observers have pointed out that these women’s voices and actions are biased towards urban middle-class interests and out of touch with the suffering of women in the migrant workforce or other lower social strata. But is the Young Feminist Activism phenomenon in China really a largely elite urban project? This essay argues that while the feminist upsurge in China shares the common anti-authoritarian features of many urban, middle-class-oriented movements, it is by no means confined within the urban elite sphere.

- Zhang Yueran. 2018. ‘The Jasic Struggle and the Future of the Chinese Labour Movement.’ Made in China Journal vol. 3, no. 3: 12–17; Zhang Yueran. 2020. ‘Leninists in a Chinese Factory: Reflections on the Jasic Labour Organising Strategy.’ Made in China Journal 25 June, online only; Au Loong Yu. 2019. ‘The Jasic Mobilisation: A High Tide for the Chinese Labour Movement?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 4: 12–16; Kevin Lin. 2019. ‘State Repression in the Jasic Aftermath: From Punishment to Preemption.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 4, no. 1: 16–19; Anonymous. 2019. ‘Orwell in the Chinese Classroom.’ Made in China Journal 27 May, online only.

In July 2018, workers at the Shenzhen Jasic Technology Co. Ltd decided to push for unionisation in order to address a wide range of workplace grievances, such as an inflexible work schedules, under and late compensation for overtime work, excessive and unreasonable fines, and stringent workplace regulations (for instance, regulations that restricted access to bathroom breaks). Unlike most worker grievances in China, the Jasic case was unusual in that it was supported openly by a group of self-proclaimed Maoists and Marxist university students, along with a small group of older citizens. This coming together of workers and students unleashed a wave of repression that continues to reverberate to this day. These essays put the mobilisation in context, reflecting on the advantages and the limitations of the strategy implemented by these activists and on how this has impacted the Chinese labour movement at large.

- Anita Chan. 2020. ‘American Factory: Clash of Cultures or a Clash of Labour and Capital?’ Made in China Journal, vol. 5, no. 1: 174–79; Stella Hong Zhang. 2019. ‘Service for Influence? The Chinese Communist Party’s Negotiated Access to Private Enterprises.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 4, no. 3: 41–45.

Neflix’s 2019 hit movie American Factory documents the attempts of the owner of the Fuyao Glass Company—an enterprise that supplies 70 percent of the windshields and windows for China’s automobiles—to open a factory in a disused General Motors (GM) assembly plant in Dayton, Ohio, a city that was once one of the sites of American industrial power. When these two very different groups of employees were thrown together, it seemed like the perfect formula for a classic ‘clash of cultures’ situation. Indeed the word ‘culture’ is mentioned many times in the film by both the Chinese and the Americans. But what exactly is this ‘culture’ and what does it entail when it comes to labour organising?

- Anita Chan. 2020. ‘From Unorganised Street Protests to Organising Unions: The Birth of a New Trade Union Movement in Hong Kong.’ Made in China Journal, 15 July, online only.

For several months in 2019, the world’s news media was front-paging the Hong Kong anti-extradition bill movement almost on a daily basis. However, towards the end of the year, with the street violence subsiding and the fierce battles at two universities ending in the defeat of the students and their supporters, the international media seemed to lose interest. As global attention shifted elsewhere, one might have assumed that the movement had died a natural death. It did not. It is from here that this essay picks up the narrative. It was at that point that the movement branched off in a new direction, with activists beginning to set up trade unions and transitioning towards a nascent organised movement.

Module 5: The Future of Labour

- Tommaso Facchin and Ivan Franceschini, excerpt from the documentary Dreamwork China (2011).

In the suburbs of Shenzhen, in Guangdong province, young workers talk about their lives, existences built on a precarious balance between hope, struggles and wishes for the future. Around them activists and NGOs strive to give sense and meaning to words like rights, dignity and equity. This short video is an excerpt from the full-length documentary (55 minutes), written and directed by Tommaso Facchin and Ivan Franceschini.

- Jenny Chan. 2017. ‘#iSlaveat10.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 2, no. 3: 20–23.

In January 2017, Apple celebrated the tenth anniversary of the launch of the first model of the iPhone. After a decade, has Apple’s extraordinary profitability been coupled with any greater social responsibility? Are the Chinese workers who produce the most lucrative product in the electronics world seeing improved working and living conditions? This essay provides some answers by focussing on two issues: freedom of association and the situation of student interns.

- Julie Yujie Chen. 2018. ‘Platform Economies: The Boss’s Old and New Clothes.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 3: 46–49.

The recent growth of China’s platform economy is jaw-dropping. What Chinese platform workers have experienced is the epitome of the intertwining transformations that digital technologies have engendered, not only in the Chinese economy and society, but also in global capitalism more generally. This essay argues that a better understanding of the situation of these workers will inform us about China’s economic conditions and provide a glimpse into the future of Chinese labour struggles.

- Mimi Zou. 2018. ‘Rethinking Online Privacy in the Chinese Workplace: Employee Dismissals over Social Media Posts.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 3: 50–55.

The increasing popularity of social media usage in the workplace, as well as rapid advancements in workplace surveillance technology, have made it easier for employers in China—as elsewhere—to access a vast quantity of information on employees’ social media networks. Considering that Chinese privacy and personal data protection laws have been relatively weak, there have been a growing number of cases brought before courts in China involving employer access to, and use of, employee social media content. This essay examines a number of these cases.

- Li Xiaotian. 2019. ‘The 996.ICU Movement in China: Changing Employment Relations and Labour Agency in the Tech Industry.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 4, no. 2: 54–59.

Beginning in March 2019, the 996.ICU movement has signalled growing resentment among tech workers in China regarding the sector’s overtime work culture. The mobilisation emerged in the context of growing discontent among employees in China’s tech and Internet industry due to normalised overtime, stagnant salary and benefit growth, and health damage caused by demanding management. Still, according to this essay, the movement did not generate further solidarity because it failed to advance any structural critique, limiting itself to producing a nostalgia of the more reciprocal employment relationship of the recent past.

- Huang Yu. 2018. ‘Robot Threat or Robot Dividend? A Struggle between Two Lines.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 3, no. 2: 50–55.

With China being the world’s largest market for industrial robots, robotisation has become a hot topic in the Chinese public discourse. While media reactions have been polarised between those who fear large-scale displacement and those who emphasise the rise of newly created jobs, there has been little solid research looking into the impact of robotisation on labour market and shop floor dynamics. This essay assesses both the ‘robot threat’ and the ‘robot dividend’ discourses, offering some views on how workers should react to the ongoing technological revolution.

- Xu Hui. 2020. ‘The End of Sweatshop? Robotisation and the Making of New Skilled Workers in China.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 5, no. 1: 40–43.

In the past few years, the Chinese labour market has experienced a transition from surplus to shortage of labour, which has led to increased wages for ordinary workers. In such a context, since 2015 the Chinese authorities have pursued a policy of industrial upgrading based on the robotisation of the manufacturing sector. This essay explores the impact of such rapid-employ, large-scale robotisation on labour relations in Chinese factories.

- Loretta Lou. 2019. ‘Bullshit Jobs: A Conversation with David Graeber.’ Made in China Journal, vol. 4, no. 2: 138–43.

Is your job a pointless job? Does it make a meaningful contribution to the world? If your job was eliminated, would it matter to anyone? It has been estimated that across the developed world up to 40 percent of workers—especially those in administration, finance, and the legal professions—saw their jobs as a form of meaningless toil analogous to the Greek myth of Sisyphus. These white-collar workers covertly think that their jobs are not only useless, but sometimes harmful to society. With increased automation, a fifteen-hour workweek is not unachievable, but on average working hours have increased rather than decreased over the past few decades. In his work, David Graeber examines this epidemic of futility, and offers a theory for human freedom and social liberation.

Cover Photo originally by Esmee Van Heesewijk.