Bilingual Education in Inner Mongolia: An Explainer

China today is in the midst of closing out a three-quarters of a century experiment. That experiment was in minority-language education for certain select ethnic groups: Mongols, Uyghurs, Tibetans, Kazakhs, and Koreans. A heritage of both China’s decentralised past and the Soviet model, minority-language education is now being replaced by a new model of ‘bilingual education’ in which Chinese is the language of instruction and minority languages are at most a topic of instruction, one hour a day. This summer, the new model was brought to Inner Mongolia where it has sparked perhaps the largest wave of protest in almost three decades. What is this new model of ‘bilingual education’ and why is Inner Mongolia now the epicentre of resistance?

Q: What is the ‘bilingual education’ issue in Inner Mongolia?

Q: What will the practical effect of this policy on the school day be?

Q: What’s the stated rationale for the policy?

Q: Isn’t ‘Bilingual Education’ a good thing for minority languages?

Q: Can Mongolian language abilities be preserved under ‘Bilingual Education’?

Q: Is Mongolian language being banned? Is the Mongolian script being banned?

Q: How long has this policy been in the works?

Q: Is this a local policy, or a Beijing policy?

Q: How long has Mongolian-medium education existed in Inner Mongolia?

Q: Why is Mongolian-language education so important in Inner Mongolia?

Q: Don’t all Mongols speak Chinese anyway?

Q: What percentage of ethnic Mongols in Inner Mongolia still speak Mongolian?

Q: Do Mongol parents still desire Mongolian-language education for their children?

Q: How are Inner Mongolian activists responding to this new policy?

Q: How have the authorities responded?

Q: Who’s leading the resistance? Are they outside Inner Mongolia?

Q: Why adopt this new policy now? Are there long-term causes?

Q: Are there specific short-term reasons?

Q: How likely is it to be successful?

The Policy Change

Q: What is the ‘bilingual education’ issue in Inner Mongolia?

A: This summer, the Inner Mongolian Educational Department announced a plan to make changes to education throughout the nine years of compulsory schooling in Inner Mongolia. The plan is to begin transitioning to the state-compiled textbooks for ‘language and literature’, ‘morality and law (politics)’, and ‘history’ classes. The key point is that these classes will be taught in the national common language—Mandarin Chinese. This policy will be formally implemented from the beginning of school, this 1 September, starting with ‘language and literature’ in first and seventh grade. Next year, it will be extended to ‘morality and law’ and then to ‘history’ in 2022. So from 2022, if all goes according to plan, all students in Inner Mongolia will be taking all three of these classes solely in Chinese, on the basis of the Chinese state-compiled textbooks. Previously, in many schools in Inner Mongolia, all of these subjects were taught in Mongolian through high school.

Q: What will the practical effect of this policy on the school day be?

A: Currently, Inner Mongolian schools have six to seven hours of class per day. In a typical Mongolian-medium school, all the classes will be in Mongolian for the first two years, and all the language and literature classes will be focussed on Mongolian language and literature. From third grade on an hour a day of Chinese language would be added, and from sixth to tenth grade a foreign language would be added.

The practical effect of this reform will be to change three subjects of instruction into Chinese-medium courses. Mongolian language classes have been promised to continue alongside ‘language and literature’ (Chinese) and the remaining classes—currently mathematics, sciences, art, music, and physical education—will continue to be taught in Mongolian. But the policy documents envision the new subjects being given greater prominence in the curriculum and taught at lower levels. At the same time, there is also a promise of no increase in school hours. Thus the share of the class hours for the ‘local classes’ per week is being reduced in order to increase the class hours for the ‘national classes’, which cannot but reduce the hours conducted in Mongolian.

One immediate area of concern is the job security of the existing teaching staff. According to the official documents, most teachers currently teaching in Mongolian should be able to switch to teaching in Chinese over the summer with some additional training. In certain areas, they envision having to bring current or recently retired teachers with Chinese-teaching experience to assist in the transition. Official documents also strive to assure teachers that the changes will not affect their job seniority or pensions, and that they will be given opportunities for retraining if needed.

In the long run, this policy will have knock-on effects into college. At present, Inner Mongolian universities have Mongolian-medium classes in history and other social sciences. What will happen when there are no more students with grade-school training in Mongolian language in these topics? Similarly, employment chances for those who have trained to teach history, morality and law, and language and literature in Mongolian can only decline sharply.

Q: What’s the stated rationale for the policy?

A: According to the official rationale, the main benefit of this change is that the new national textbook and curriculum standards for these three classes—‘language and literature,’ ‘morality and law,’ and ‘history’—are of the highest quality. This textbook has already been implemented from 2017 in ethnic schools in Xinjiang and from 2018 in ethnic schools in Tibet—Tibetan- and Uyghur-medium schools had already been eliminated and the law mostly affected the Mongolian and Shibe schools in those regions. The documents insist that other classes will not be affected, and that the ongoing Mongolian (and Korean) language and literature class will not be influenced.

At the same time, the documents prominently cite Chinese president Xi Jinping’s emphasis on having a shared language as a crucial link for communication and, in turn, for mutual understanding and ‘common identification’. They also cite improving mastery of the common national language as the basis for more success in the ‘job market, in receiving modern arts and sciences education, and in integrating into the society.’

Left unanswered is the question: why couldn’t the new textbooks have been simply translated into Mongolian? In fact, the curriculum in use for morality, politics, and history in Inner Mongolia’s Mongolian-medium schools today is translated from Chinese, with no specific Inner Mongolian content. The only exception currently is Mongolian language and literature.

Q: Isn’t ‘Bilingual Education’ a good thing for minority languages?

A: In many countries, an hour a day every day in school for a minority language would be considered a great advance in multicultural education. In Inner Mongolia, however, it represents a dramatic decline in the educational status of the language. In Mongolian-medium schools in China up until the present, all the classes up through grade twelve are in Mongolian, with classes teaching Chinese and foreign languages added in from third grade on.

Theorists of education speak of the language as either the ‘medium’—the language in which the teaching occurs—or the ‘subject’—that which is being taught. The key issue here is that under the new policy the subjects that will be taught with Mongolian as the medium will be cut back severely.

Technically, even now Mongolian-medium schools are ‘bilingual’ from the third grade onward since Chinese language is also taught in them. Thus, some in China speak of the current ‘Model 1’ bilingual education versus the new ‘Model 2’ bilingual education. But in general, activists reject the term ‘bilingual education’, seeing it as a way of prioritising Chinese over Mongolian; historically the experience of Xinjiang and Tibet shows that this is a realistic fear.

Q: Can Mongolian language abilities be preserved under ‘Bilingual Education’?

A: There are reasons to doubt whether this is possible.

First of all, there is an obvious trend—going from studying all your classes in Mongolian to just a few is a massive downgrade. This is a result of central government policy to improve familiarity in the ‘national common language’; will further downgrades be coming down the pipeline? In Xinjiang, a policy of ‘vigorous promotion’ of ‘bilingual education’ began in 2004 and by 2006 there was purely Chinese-language education down to the kindergarten level in some rural areas.

Secondly, as numerous studies of Mongolian-medium schools in Inner Mongolia have shown, even there, the ‘hidden curriculum’ clearly treats Chinese knowledge and Chinese institutions as more important than Mongol knowledge and Mongol institutions. As a result of this hidden curriculum, Mongol children even in Mongolian-medium schools often neglect Mongolian-oriented curricula—a neglect that frequently leads to regret after ethnic consciousness-raising in college. The very emphasis placed on the three national-level classes makes them obviously important subjects—the implication that truly important subjects need to be taught in Chinese will not be lost on Mongolian pupils.

Third, the change will cripple the ability of those Mongol children in Mongolian-medium schools to express themselves in their mother tongue on a full range of subjects. Literacy is not an on/off thing, but occurs in a range of social functions, which must be practiced to be successfully mastered. The removal of politics, morals and morality, and history from the range of subjects that Mongolian children will be trained to read, write, listen, and speak about in their mother tongue will further weaken the language, pushing it closer towards a ‘kitchen language’ that can only be used for in-family conversations and lacks vocabulary and rhetorical sophistication for public written and oral use.

Within China, the discourse of development is absolutely pervasive—all aspects of society can be ranked as ‘developed’ or ‘backward’ and all movement should be from ‘backwards’ to ‘developed.’ With regard to language, this perspective means that languages can be ‘developed’ and that all people in China have a constitutional right to ‘develop’ their native language. Article 4 of the Chinese Constitution states: ‘All nationalities have the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages.’ Schooling is the key site for such development. When a central policy is implemented that says Mongolian language is no longer capable of serving as the medium for the vital subjects of language, politics, morals, and history, the message in a Chinese developmental context is clear: Mongolian is backward and cannot be developed.

Q: Is Mongolian language being banned? Is the Mongolian script being banned?

A: Definitely not. Even strong opponents of the proposed change recognise that in ethnic Mongol schools in Inner Mongolia, Mongolian will continue to be taught as a subject—although critics say that this amounts to treating the Mongolian mother tongue ‘like a foreign language’. Nor has there been any moves to ban the use of Mongolian language in public or in schools outside of class. Mongolian language radio and TV are continuing, and given their importance in projecting a favourable image of China to independent Mongolia are unlikely to be cut back. Limitations on Mongolian-language social media platforms like Bainu appear to have been temporary, and they are apparently operating again.

The Policy’s Background

Q: How long has this policy been in the works?

Policy documents mention that the unified national curriculum in the three subjects was first rolled out in September 2017. It was first implemented in Xinjiang in 2017 and then in Tibet in 2018. Reports indicate that implementation of this policy was attempted in a Mongol banner (county) of Shiliin Gol League also in 2018, but was dropped in the face of quiet resistance. Official documents say that this year, the new curriculum is being extended to schools in Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Jilin, Liaoning, Qinghai, and Sichuan. The focus appears to be the remaining Mongolian language schools in China, as those regions, with the exception of Sichuan—where Tibetan is the main minority language—all have Mongolian autonomous districts with Mongolian language schooling. However, details on application to the other five province-levels units are lacking.

As far as this round in Inner Mongolia goes, this policy appears to have first been disclosed around June 2020 in Tongliao municipality—an area in southeastern Inner Mongolia with a large ethnic Mongol population—in connection with a visit on 4 June by a delegation led by Ge Weiwei, the deputy section chief of the Ethnic Education Section of the Ministry of Education, accompanied by a ‘researcher’ from his department, Chogbayar. During that visit he emphasised deficiencies in the command of the ‘common national language’ and the need to improve it. By late June, reports emerged that teachers in the Tongliao municipality would have to begin the first of the three subjects (language and literature) in Chinese in September. By Monday, 6 July, the first petitions against this policy began to circulate on WeChat, at this point speaking only of Tongliao. On 17 August, the extension of this policy to all of Inner Mongolia was first announced by the Regional Department of Education in closed meetings, and all subordinate administrative units were ordered to begin planning implementation from 18 August. On 23 August, posts by Mongols related to the topic of ‘Bilingual Education’ began to be systematically removed from social media in Inner Mongolia. Han Chinese outside the region, however, report being still able to discuss the topic.

Q: Is this a local policy, or a Beijing policy?

The participation of national-level educational administrators like Ge Weiwei, and even more the emphasis on a nationally approved curriculum and a steady process of implementation, show that this policy is being driven from Beijing. Some of the designers at the national level are ethnic Mongols like Chogbayar and the details of implementation are being worked out in Höhhot, but the overall initiative is undoubtedly from the centre. Yet at the same time, regional officials are being pushed out front to take the lead in visibly implementing it.

Q: Is this related to issues in Xinjiang and Tibet? To Xi Jinping’s policies of ideological centralisation?

A: The impetus behind the national-level policy to revise and issue a new central curriculum and textbooks in language and literature, morality and law, and history is undoubtedly part of the turn towards Chinese nationalism and ideological transformation under the Xi administration. By this time, however, even if local conditions are still impeding full implementation of Chinese-medium education in remoter parts of Xinjiang and Tibet, Uyghur- and Tibetan-medium education in Xinjiang and Tibet had already been largely eliminated, and Mongolian and Korean were the only minority languages continuing to be used as media for instruction in China, at least in theory. The application of this policy to Korean areas of Jilin and Liaoning would presumably have the same effect on Korean-medium education in China.

Q: Is This Related to the ‘Second Generation Ethnic Policy’ (第二代民族政策) promoted by policy academics in Beijing?

A: Yes, many members of the opposition have argued that the new policy is surreptitiously implementing this ‘Second Generation Ethnic Policy’. The ‘Second Generation Ethnic Policy’ has been advocated by figures like Professor Hu Angang of the Centre for China Studies, a think tank affiliated with Tsinghua University, Hu Lianhe, an official in the United Front Department also associated with the same centre, and Anthropology Professor Ma Rong of Peking University. These thinkers claim that the Soviet-based ethnic autonomy built into China’s constitutional structure was a mistake and should be replaced by a ‘depoliticised’ ethnic policy modelled on that of the United States, where ethnic groups have individual rights to equality but no rights to territorial autonomy and no state-supported educational or cultural maintenance. This would involve changing autonomous areas, prefectures, and counties in China into ordinary territorial units, and involve a transition to purely Chinese language education. During his trip to Tongliao, Gu Weiwei referred positively to these ideas

During this year’s delayed ‘Two Sessions’ that opened on 21 May, representatives of one of the eight legally recognised non-Communist parties in China, the Chinese Association for Promoting Democracy, submitted a proposal based on the ‘Second Generation Ethnic Policy’ viewpoint. This proposal sought a new law on the ‘National Common Spoken and Written Language’ (国家通用语言文字), arguing that new conditions in China made the existing law ‘unable to meet the needs of economic and social development and of national development.’ Specifically, this party argued that Inner Mongolia’s ethnic educational policy was out of line with the promotion of a common national language.

Although the non-Communist parties in China do not have significant political power, they often speak for public intellectuals particularly in the ‘advanced’ coastal areas of China. The proposal by the Chinese Association for Promoting Democracy shares numerous verbal similarities with the new Inner Mongolian proposal, such as the reference not to ‘Chinese language’ but to ‘National Common Spoken and Written Language’. Clearly the new policy in Inner Mongolia is in line with the thinking of many in China’s wealthier and more cosmopolitan regions that see ethnic autonomy as an outdated legacy of Soviet tutelage and a drag on developing China’s poorer and more rural West.

Education and the Mongols of Inner Mongolia

Q: How long has Mongolian-medium education existed in Inner Mongolia?

A: Formal education in the Mongolian language has existed in some form since the creation of the Mongolian alphabet in 1206. After the conversion of the Mongols to the Gelug (Yellow Hat) school of Tibetan Buddhism in 1581, Tibetan language education became strongly dominant for the 40 percent or more of children who spent some time in the monasteries. However, even after the Mongols came under the control of China’s last dynasty, the Manchu Qing (1636–1912), the autonomous Mongol principalities, or ‘banners,’ continued to use Mongolian as the official language of administration, together with Manchu (Chinese was not allowed to be used in administration). Scribes in the local governments were expected to train a regular number of pupils each year. After 1901, as Beijing turned to a new settler colonialist policy of replacing Mongol herders with Han farmers, new Chinese schools were founded alongside the Tibetan-language monasteries. In response, a ‘New Schools’ movement promoted secular Mongolian language education, alongside Chinese language, as a new avenue for development and liberation. From 1931, in Japanese-occupied Inner Mongolia, these schools became part of a broad Mongolian-medium school system. After 1945, the Chinese Communist Party seemed to ‘get’ that aspiration for Mongolian cultural development in a way that the Nationalist Party did not. The Party won crucial support of Mongols in the Chinese Civil War by affirming this policy, which has continued, although in increasingly limited form, to the present.

Q: What are the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) policies on minority-language medium education? How have they changed?

A: From the founding of the PRC up through the 1980s, five minority languages were used as media for education: Mongolian, Uyghur, Tibetan, Kazakh, and Korean. In these languages pupils learned not just language and literature of their own language, but also math, natural and social sciences, and history. This policy continued in rural areas even through the Cultural Revolution, at least in Inner Mongolia. After 2000, Tibetan and Uyghur language education became increasingly restricted, in response to political unrest and the government’s perceived need to monitor non-Chinese speakers. In Tibet, the beginning of Chinese language was advanced from third grade to first in 2001, and from 2010 to the present ‘bilingual education’ has been used as a label for promoting a movement from Tibetan as medium and Chinese as a subject to Chinese as the medium and Tibetan as the subject. In Xinjiang the transition was much more abrupt. From 2002 to 2005, Uyghur- and Kazakh-medium education in Xinjiang was replaced by Chinese-language education, with at most a few hours of Uyghur per week. Mongolian and Korean are thus the last of the five minority languages in which education in a full range of subjects occurs in the minority languages.

Q: Lots of dialects in China, like Cantonese and Hokkienese, don’t even have one hour a day in the class to teach their language. Shouldn’t Inner Mongolians be grateful to get that?

A: Mongolian language is completely unrelated to Chinese—it is not very closely related to any other language, but it is fairly similar in many ways to Turkish and Manchu. Its script is also a unique alphabet, written vertically, that ultimately derives from the Middle East. The Mongolian literary tradition that begins with the Secret History of the Mongols (c. 1252) and continues with poems, histories, philosophy, novels, and other writings is completely independent of the Chinese tradition. Thus, it cannot be compared to dialects of Chinese like Shanghainese (Wu), Fujianese (Hokkiennese), Cantonese, and so on, in which famous figures of those provinces have long written in classical Chinese as a common language of all Sinitic language speakers.

Q: Why is Mongolian-language education so important in Inner Mongolia?

A: Even as steppe nomads, Mongols traditionally valued education. Whatever may be the case for other nomadic conquerors, the Mongols valued literacy, education, and religious and philosophical traditions. Legends of the Mongols destroying libraries in Baghdad or elsewhere are just that, legends, with no basis in fact. Before the twentieth century, Buddhist learning was highly valued, as were the traditional histories and rituals of Chinggis Khan and his successors. Although schools were small in scale, they were densely inhabited. Owen Lattimore reported in the 1920s that in his experience, the nomadic Mongols were more literate than the Chinese farmers colonising their grasslands.

As a result of this ‘New Schools’ movement in the early twentieth century, schooling acquired a deep significance for Inner Mongolians. The movement was also closely associated with Mongolian nationalism, and its proponents often also participated in pan-Mongolian movements to join independent Mongolia (then the Mongolian People’s Republic). But even when nationalist political movements reached a dead end, the importance of education continued. For many, cultural nationalism and educational renewal became a substitute for political nationalism. Enlightenment and schooling became the way to preserve the future of the Mongol people. Public schools teaching Mongolian thus acquired something like the significance for Mongols that Buddhist monasteries have for Tibetans and Islamic holidays and shrines have for Uyghurs.

Q: Don’t all Mongols speak Chinese anyway?

A: The misleading impression that the Mongols have been completely assimilated already is due to several factors: 1) Unlike the Uyghurs and Tibetans, the Mongols in Inner Mongolia did not have a significant urban tradition, and thus had no urban districts with a distinctively Mongol urban residential architecture—the Tibetan-style Buddhist monasteries of Höhhot and a few other cities are separate cases. 2) Mongols in urban areas are thus as a rule employed in Chinese enterprises and work units and speak relatively fluent Chinese. 3) The entire infrastructure of tourism and communication for visitors to Inner Mongolia is controlled and conducted in Chinese, thus establishing an expectation that Mongols meeting people from outside Inner Mongolia, whether fellow citizens of the PRC or foreigners, will of course speak only in Chinese, apart from a few stereotyped phrases.

Those who can actually speak Mongolian, whether visitors from independent Mongolia or the occasional specialist in Mongolian studies who speaks Mongolian, find, however, that there is a whole second subculture of Mongolian speakers in urban areas of Inner Mongolia and in a few cities outside Inner Mongolia, such as Beijing. Inner Mongolian social media, such as Bainu, provide opportunities to communicate in a purely Mongolian environment.

Q: Mongols are only 17 percent of the population of Inner Mongolia. Isn’t it impossible for them to think of preserving Mongolian language over the long term?

A: Although the Mongols are a very small percentage of the Inner Mongolian population as a whole, this statistic is very misleading. Inner Mongolia has several large cities and densely inhabited farming counties. But it also has a large number of ‘banners’—traditionally Mongol county-level units—where herding or mixed herding and farming take place. In ten such ‘banners’ in Inner Mongolia, ethnic Mongols are the absolute majority; in another five, ethnic Mongols are more than a third of the population. Even in ‘banners’ where Mongols seem a small percentage, they often form local majorities. Since, however, areas where Mongols are the majority tend to have low population density, they can be easily overlooked in aggregate statistics.

That said, the process of urbanisation has undoubtedly accelerated the residential integration of Mongol and Han Chinese populations. The general Chinese trend of urbanisation has been accelerated in pastoral regions by targeted programmes such as ‘ecological resettlement’ (生态移民), which has dealt with real or purported over-grazing in steppe areas by resettling the majority of the residents to apartment blocks built in neighbouring towns or urban areas. Although these relocations have had varying results on the ground, they were always accompanied by the closing of rural (as a rule, Mongolian-medium) schools. At the same time, the expansion of mining has established new communities, almost purely Han Chinese, in previously Mongol areas.

This has been accompanied by an increase in intermarriage of Mongols with Han. In 1982, about 14 percent of all marriages were mixed marriages between Mongols and Han; today, among newly married Mongols, 40 percent of marriages are contracted with Han partners. This number remains very uneven, however, with strong pockets of mostly Mongol communities where intermarriage is quite rare.

Q: What percentage of ethnic Mongols in Inner Mongolia still speak Mongolian?

A: Answering this question is difficult due to issues of definition both of who is a Mongol and what does it mean to ‘use’ a language. In the early 1980s, a large number of people previously considered Han who could claim one Mongol grandparent changed their registration to Mongol for a number of reasons; socially, however, most of them were not part of Mongol social circles and virtually none of them spoke Mongolian. It may be somewhat artificial thus to consider every person registered as a ‘Mongol’ by Chinese minzu (民族, ethnicity or nationality) as being Mongolian for sociolinguistic purposes. Similarly, it is common for people to answer questions about native or home language more according to how they think they should answer or would like to be able to answer.

As of 1988, it was estimated that almost 80 percent of the Mongols spoke Mongolian as their main or mother tongue. At present, this has dropped to around perhaps around 60 percent. As with intermarriage and demographics, this single figure conflates vastly different rates from districts where Mongolian language ability is virtually unknown among the resident Mongols to districts where it is still virtually universal.

Q: Do Mongol parents still desire Mongolian-language education for their children?

A: After China’s move towards a free market economy in the 1990s, the previous model for minority language education definitely showed stress. Although autonomous areas in China hire relatively large numbers of minority cadres, educators, and cultural workers, where the minority language is valued, commercial and industrial organisations, particularly if they are privately owned and Han dominated, tend to have overwhelming Chinese speaking environments. Such enterprises are much less likely to hire from Mongolian-medium schools.

As a result, the number of Mongols choosing Mongolian-medium school has slowly declined, from almost 60 percent in 1990 to a little over 30 percent today. At the same time, certain new opportunities for Mongolian-speakers have opened up, particularly representing Chinese investors operating in independent Mongolia, or Mongolian firms operating in China. Many Inner Mongolian students now also choose to study abroad in independent Mongolia, and Chinese government offers generous scholarships to students from independent Mongolia to study in Inner Mongolia.

Q: How does the opposition deal with the claim that this policy is necessary to resolve the minorities’ backwardness, illiteracy, and isolation from national life?

A: The ‘Second Generation National Policy’ policy school builds on a stereotype of all minorities in China as ‘poor’ and ‘backward’. This impression is widely shared in China, even by Mongols themselves. Arguments that separate minority-language education systems must thus be inferior in quality and a drag on development have a lot of surface plausibility in a Chinese context.

If backwardness is measured by illiteracy, however, this impression is false in Inner Mongolia. In fact ethnic Mongols in Inner Mongolia have a higher rate of literacy than the ethnic Chinese of Inner Mongolia. In 1982, illiterates were 24 percent of ethnic Mongols in Inner Mongolia over 12 years of age; for Han Chinese, the comparable figure was 26 percent.

Nor has Inner Mongolian education lacked quality. In response to the current crisis, a writer or writers using the pseudonym ‘Red Horse Reading Club’ pointed out that Shabag village in eastern Inner Mongolia has only 1,268 people, all Mongols educated in Mongolian, but it has produced ten current or graduate PhDs students, 17 MAs, and more than 290 university graduates. As he concluded, ‘This nationality education system in Inner Mongolia is the successful realisation of the Party’s nationalities policy’—it’s not broken, so it doesn’t need fixing.

Opposition to the New Policy and Prospects for the Future

Q: How are Inner Mongolian activists responding to this new policy?

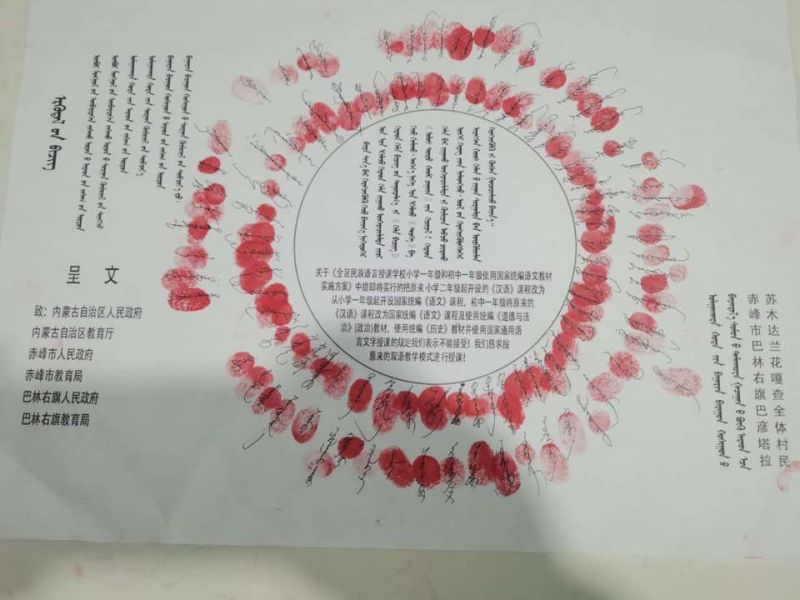

A: Currently Mongols in Inner Mongolia are actively petitioning against it. Within two days of the public announcement of the policy on 6 July, 4,200 petitions had already been circulated. Undoubtedly vastly more have signed since then. Following regular Chinese practice, petitioners have been giving their fingerprints in red ink and sometimes their ID numbers along with the signatures; many such petitions have been shared on social media. The opposition is said to be particularly strong in Shiliin Gol League, the east-central region of Inner Mongolia and the region that sets the dialect standard for Mongolian language. Some have shared videos in which sumu (township level units) show petitions claiming that 100 percent of the households have signed.

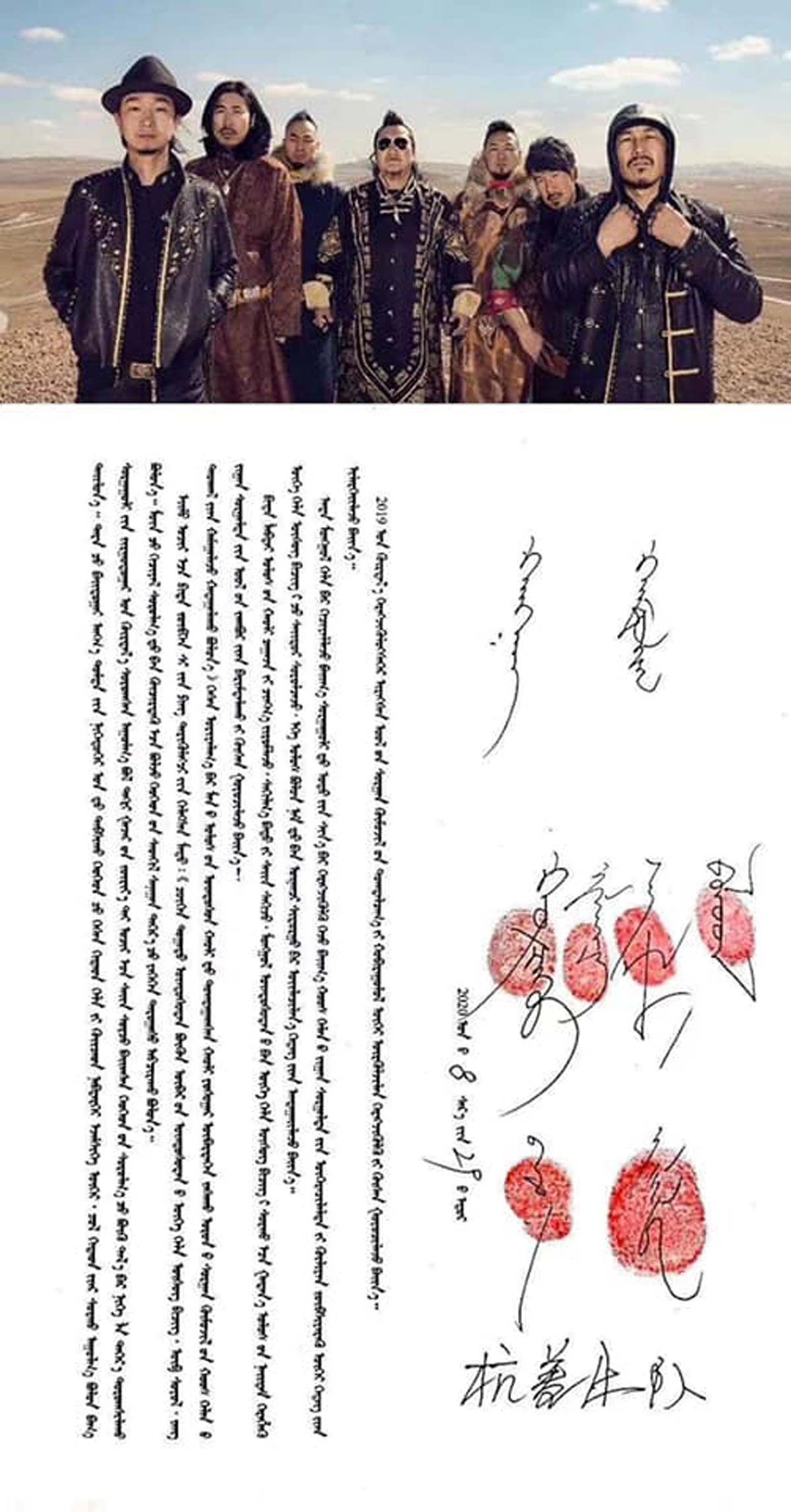

In one petition shared on social media, 85 teachers from the Mongolian Ethnic Primary School in Plain Blue Banner (Zhenglan Qi) in Shiliin Gol signed their names. In signing, they imitated Inner Mongolia’s famous pre-revolutionary ‘circles’ or duguilang resistance groups, who signed their names in a circle so that leaders could not be singled out for punishment. Many other schools have followed suit. Nine of Inner Mongolia’s most popular bands have also shared petitions against the new proposal on social media.

Anonymous leaflets have also actively circulated, calling for demonstrations to take place in each of the twelve major administrative centres of Inner Mongolia. They also advocate a student-and-teacher strike beginning with the first day of school on Tuesday, 1 September. Already videos have been shared of rural parents gathering at town boarding schools to take their students back home. It is difficult to tell from outside the region, but the call for a student-and-teacher strike actually seems to be getting some traction.

The overwhelming emphasis of the petitioners is that Mongolian-medium education has been successful and has existed in the PRC for 70 years. They thus claim to be simply defending an existing, successful policy, not demanding any new rights or any change in China’s constitutional structure.

Petitioners accuse the new policies of violating both the PRC’s constitutional guarantee of the right to use and develop their own language and the Autonomy Law of the PRC, of violating the spirit of Xi Jinping Thought, and of damaging ethnic unity between Mongols and Han. Slogans at the projected demonstration are supposed to be ‘non-political’ and focussed solely on protecting legally guaranteed language rights. Undoubtedly there is a large amount of rhetorical calculation in this stance, as well as sincere commitment to maintaining the constitutional status quo. How much pragmatism and how much sincere commitment is impossible to say.

It should also be noted that proponents of the ‘Second Generation Ethnic Policy’, which many Mongols have identified as the source of this policy, do indeed regard the constitutional framework of China’s ethnic policy to be fundamentally flawed and in need of revision. To that degree, activists’ point that they are the ones, and not the proponents of the new policy, who are standing for the PRC’s existing constitutionally-based autonomy policy is not just rhetoric, but a fact.

Q: How have the authorities responded?

A: It seems clear from the openness of the petition and demonstration activity that there must be considerable behind-the-scenes support for the movement from ethnic Mongol cadres and supportive Han colleagues. Social media discussion of the topic at first was not blocked, despite the sub rosa nature of the policy roll out. But in a harbinger of things to come, Chimeddorji, a famous historian with his doctorate from Bonn University and head of the Mongolian Study Center of Inner Mongolian University, was removed from his position on 7 August for making a nine-minute viral video criticising the new proposal.

On 23 August, the Mongolian social media application Bainu was closed, and discussions of ‘Bilingual Education’ were removed from WeChat and other Chinese sites. Numerous Mongols report receiving late night phone calls from police officers telling them to cease participating in the movement and threatening that those who participate in the upcoming demonstrations or strikes will be fired.

On 28 August, police in Höhhot began breaking up public meetings to collect petitions and activists began to receive invitations to come to the police office ‘to have tea’ (a common method of warning in China).

The next day, state-owned media gave high-profile official reassurance in the name of the Inner Mongolian Party secretary Shi Taifeng that five things would not change:

- No other change to the curriculum in Inner Mongolia’s ethnic primary and junior high schools;

- No change to textbooks;

- No change to the language and script of instruction;

- No change to the hours of Mongolian and Korean classes;

- No change to the current model of bilingual instruction

This ‘Five No Changes’ (五个不变) slogan just reiterates assurances already given in the official documents; more important is that it puts the Party hierarchy firmly behind the new policy.

Q: Is this the first time the Inner Mongolian government has tried to curtail or eliminate Mongolian-medium education?

A: No. Beginning in the 1990s, there have been sporadic attempts to limit Mongolian-medium education. Such a proposal was made in 1993, but it was defeated by a mobilisation of cadres, particularly from Eastern Inner Mongolia, where traditions of Mongolian language education are particularly strong, and which is the place of origin for many of Inner Mongolia’s ethnic cadres. There was another attempt in 2018, which again appears to have been defeated through mobilisation of cadres in Inner Mongolia. These episodes established a pattern of working within the system to defend Mongolian language. In this strategy, the support of Mongol cadres is crucial. Although Mongols are only 17 percent of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region’s population, they are over a third of the cadres and include the region’s chair, and many vice chairs (although not the secretary of the region’s Communist Party committee).

Q: Who’s leading the resistance? Are they outside Inner Mongolia?

A: So far, the resistance is public at the grassroots, but anonymous in leadership, if any, and entirely rooted in Inner Mongolia. It is hard to believe that this degree of opposition is possible without significant leadership, probably from ethnic Mongol cadres within the Inner Mongolian government as well as the teachers themselves. But all proponents on social media picture themselves simply as ordinary teachers, students, and parents.

From the beginning, information about this new policy and resistance to it has travelled along social, local place, and kinship networks to those outside Inner Mongolia. In these networks, Mongols in Japan have played a crucial role. Until recently, Japanese was, for historical and linguistic reasons, the most widely taught foreign language in Inner Mongolia’s Mongolian-medium schools—the replacement of Japanese by English in these schools is just another aspect of the convergence of Inner Mongolian education with broader Chinese national trends. A number of Inner Mongolian scholars such as Yang Haiying have built successful careers in Japan and they have become key figures in petitioning and spreading knowledge about these movements. Similarly, the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Centre has played that role in the United States. Mongols abroad often package news of resistance in Inner Mongolia with a much more radical edge, seeing the new policy as the culmination of a long Chinese programme of assimilation. It is unclear to what degree this perspective is shared inside Inner Mongolia.

Q: We hear a lot about Tibet and Xinjiang, but not so much about Inner Mongolia. How similar are these cases? How different?

A: Compared to Uyghurs and Tibetans, Mongols in China have sometimes been positioned as a ‘model minority’—a position that is even more commonly applied to the Koreans of China. Mongolian nationalism has existed in Inner Mongolia and was a strong force from the mid-1920s through the 1940s, and has existed in covert forms through the present. However, armed resistance by anti-Communist Mongols was mostly crushed by 1952 and flight of refugees to independent Mongolia has not been common. There have not been any massive and highly visible instances of interethnic conflict like the 2008 unrest in Lhasa or the 2009 Shaoguan lynching and the demonstrations in response in Ürümchi.

From its origins in the late nineteenth century, Mongolian nationalism has been strongly secular. This secularism and common participation in the Moscow-led world Communist movement were the grounds on which Mongolian nationalist movements based in the eastern part of the region were able to forge a strong alliance with the Chinese Communist Party. This alliance was deeply damaged during the Cultural Revolution, when Mongols suffered from a massive and brutal ethnically directed purge, the so-called ‘Nei Ren Dang’ (内人党) case, based on the allegation that a secret Mongol nationalist party still existed and was controlling Inner Mongolian policy. In the words of one writer, in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, many Mongols felt that ‘In return for our milk-white kindness we received a black curse.’ These words were written about the Gang of Four but have often been taken by Mongols to apply to the Chinese state as a whole.

Despite these grievances, however, the focus of Mongolian nationalism on secular education, an area of cultural life controlled and funded by the state, has made the partnership of educated Mongols with the Party-state relatively more harmonious compared to Tibet or Xinjiang. Inner Mongolian society and culture remains ‘legible’ to Han Chinese in a way that Uyghur and Tibetan society and culture, seen through the lenses of Islamophobia and secularist discourses about ‘primitive superstition’, has not been.

There are certainly nationalists in Inner Mongolia who think outside the Chinese constitutional framework. But Mongol nationalists are far less openly radical and the repressive powers of the Chinese state are far less in evidence in Inner Mongolia than in Tibet or Xinjiang—a fact often lamented by Mongol nationalists outside China. Yet when dissidence has emerged, such as in the 2011 wave of protests over a protesting herder being killed by a truck driver for a coal mine, the ‘carrot’ brandished along with the ‘stick’ of repression has usually taken the form of support for Mongolian cultural and educational institutions.

More importantly, even among those adjusted to the system, there is a strong sense of a Mongol ethnonational community with corporate interests that can be furthered by the Chinese state—or betrayed. The ‘model minority’ positioning that Mongols often embrace, of loyalty freely given to the Chinese state, has at the same time the possibility of turning into claims of Chinese bad faith. Claims by activists that the new policy endangers ‘ethnic unity’ are an implicit threat that such sentiments of betrayal could be reengaged today in response.

Q: Why adopt this new policy now? Are there long-term causes?

A: Over the long term, Mongolian-medium education has been in decline, its percentage of Mongolian school age children dropping by about half since 1990. Urbanisation, accelerated by ‘ecological migration’ and other policies, has diminished residential segregation. The changing labour market makes it more difficult for Mongolian-medium school graduates to find jobs. At the same time, the rise of Chinese nationalism, and the sense that Uyghur and Tibetan nationalist movements threaten China’s geopolitical interests, and the new ‘Second Generation Ethnic Policy’ movement show that tolerance for open expression of ethnic diversity in public life is waning.

All of these factors have made implementation of this policy more thinkable. Yet even now, it is important to remember that the implementing documents envision the possibility of needing large numbers of new and temporary teachers to make up for the lack of existing Chinese-trained teachers. Mongolian-language education may have been ailing, but it is by no means dead.

A comparison can be made here with the Buryat Mongols of Siberia. After the Russian Revolution, Buryat Mongols, with help from the Russian Communist government, created a system of ethnic Buryat-language medium schools. This school system was in fact one of the models for the system adopted in Inner Mongolia from the 1940s. It survived the Stalin purges and the thaw under Khrushchev. But from middle of the 1960s, the Buryat-medium classes were slowly curtailed and eventually by the mid-1970s eliminated, leaving only Buryat as a subject of instruction and a skeletal infrastructure of radio and TV. Even if the market economy was not a factor in the Soviet Union’s case, many of the long-term factors used to explain these changes are similar to those at work in Inner Mongolia: urbanisation, diversification in the labour market, a retreat from earlier liberalising trends. The result was a further decline in Buryat language skills such that it is now almost a purely rural, ‘kitchen’ language, rarely spoken in public contexts, and not used even at home by the majority of urban Buryats.

Q: Are there specific short-term reasons?

A: There is no way to know at present about any specific short-term reasons for implementing the new policy. In recent years, educational and ideological centralisation and control has clearly been a focus of the Xi Jinping administration. We also know from the process of curriculum and class material unification that since 2017, the central government has been desiring greater linguistic, educational, and ideological unification in the autonomous areas. The Covid-19 pandemic removed one major possible reason for hesitation: the increasingly thick social connections between independent Mongolia and Inner Mongolia. The closing of the border with Mongolia and the rupture of personal travel between Inner Mongolia and the Mongol diaspora in Japan removed at least one possible source of uncertainty about the consequences.

Q: How likely is it to be successful?

A: The previous successful resistance in 1993 and 2018 is perhaps a model for this movement. At that time, the push for change was much less intense, and hence the popular mobilisation was much less widespread. In 2011, a wave of demonstrations occurred in Inner Mongolia, when a herder was killed by a truck driver during a local demonstration against the occupation of local grasslands by a mining company. The result was some new environmental regulations, sacking the local Party chief, and the execution of the truck driver.

But the best precedent for this movement may be the large student demonstrations of 1981–82, in which Mongol students from Inner Mongolia demonstrated against the continued prioritisation of farming over herding and the government sponsorship of outside Han migration into Inner Mongolia. Those demonstrations ended with a partial victory; policy was changed to prioritise herding and the demonstration leaders were given qualified amnesty. Presumably this is the most realistic positive outcome for the resistance now: revocation of the new policy, return to the status quo, and non-persecution of the participants and leaders.

Unfortunately, although the actual policy implementation has been at the regional level, without direct involvement of the central organs, news broadcasts announcing the policy did explicitly mention the support from the centre. Thus a retreat in which the autonomous region leadership would take the fall for mistaken policies, and the situation would return to the uneasy equilibrium of the past, seems unlikely.

Moreover, the current moment is hardly propitious. The rupture of international people-to-people ties due to the pandemic, the palpable sense of crisis in China’s relations with the outside world, the continued and unremitting repression in Xinjiang and Tibet: all make it hard to envision a public retreat being allowed by the Chinese government at this point. Smart money would have to be on a big show of repression on 1 September, a fizzling of the demonstrations, punishment of a few selected ringleaders, and a sullen acquiescence.

In the short term, the ‘Five No Changes’ slogan of 29 August would halt in the middle the transition from ‘Model 1’ bilingual education (Mongolian as medium; Chinese as subject) to ‘Model 2’ (Chinese as medium; Mongolian as subject). But even if this is where things eventually land, the need to issue loud reassurance that no further changes will be made would show that only continued resistance can slow the decline of Mongolian-medium instruction.

The call for demonstrations on 1 September specifically warns that ‘Since the opposition will probably have to go on for many days, please be spiritually prepared.’ If significant demonstrations and/or student-and-teacher strikes do emerge, the open opposition on social media and by petitions will certainly give the authorities a large number of targets if they opt for large-scale repression. If the strikes do gain traction and authorities follow through on the threat to fire striking Mongolian teachers and staff, the authorities would have the need and opportunity to transform Inner Mongolian schools in one blow. In the short run, such a response might be feasible, but it will mark a fundamental change in the relationship of ethnic Mongols, particularly the educated elites, to the Chinese state.