China’s Second-generation Ethnic Policies Are Already Here

What China’s History of Paper Genocide Can Tell Us about the Future of Its ‘Minority Nationalities’

In early June this year, officials in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (IMAR) released a new policy that would drastically undermine the use of the Mongolian language in schools, effectively replacing it as a language of instruction with Chinese (Baioud 2020). In response to this unwelcome imposition, petitions began circulating, calling for the repeal of the policy and eventually leading to street demonstrations, school boycotts, and other protests (Qiao 2020; Zhou 2020). The situation remains tense.

The policy that has been announced in Inner Mongolia, and the protests it prompted, bears many similarities to the situation in Qinghai province a decade ago. There, local government officials announced similar changes to the Tibetan-medium education system, effectively relegating Tibetan language to the status of a subject, and implementing a Chinese-medium system. These announcements were followed by street and campus protests throughout Qinghai and beyond (Wong 2010).

Meanwhile, in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) and the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), mother tongue education for Uyghurs and Tibetans has also come under fire. In Xinjiang, this culminated in an official pronouncement that, like in Qinghai and now Inner Mongolia, Chinese would become the new medium of instruction (Byler 2019). Meanwhile, in the TAR, a recent Human Rights Watch report (2020) has described how schools are under increasing pressure to ‘reduce the availability of mother tongue education’ and ‘shift to Chinese-medium teaching’. Party officials claim the universalisation of the ‘national language’ (普通话, putonghua) is necessary to promote poverty alleviation, inter-ethnic mingling, and social stability, despite the right for ethnic minorities to ‘use and develop’ their languages being enshrined in the Chinese Constitution, and mother tongue education being encouraged in law (Roche 2020).

In his recent analysis of the situation in Inner Mongolia, Chrisopher Atwood (2020) ties the government’s response there to the ‘second-generation ethnic policies’ (第二代民族政策). Earlier events in Qinghai, Xinjiang, and the TAR also seem to emerge from this new approach, thus prompting the question: what are these second-generation ethnic policies?

Second-generation Ethnic Policies

First proposed in late 2011 by two scholar-officials, Hu Angang and Hu Lianhe, the policies call on China to abandon its failed ‘hors d’oeuvres’–style ethnic policies, which they contend the Chinese Communist Party copied indiscriminately from the Soviet Union, and instead adopt a ‘melting pot’ formula more in line with Chinese tradition and international norms (Leibold 2013). This requires the abandonment of ethnic privilege and distinction, and the proactive forging of a common culture, consciousness, and identity. If such measures are not adopted, these ethnic policy reformers argue, China would share the fate of the USSR and come apart along its ethnic seams.

This reform agenda found a sympathetic ear with the appointment of Xi Jinping as Party Secretary General in 2013, and over subsequent years key parts of the policy have been gradually yet steadily implemented across China (Leibold 2015 and 2019). This involves not only the universalisation of putonghua-medium education, but also the scaling back and eventual elimination of a range of preferential policies (优惠政策) protected under the Chinese Constitution and the 1984 Law of Regional Ethnic Autonomy.

Ethnic minorities like the Mongols, Tibetans, and Uyghurs no longer have special exceptions to family planning laws. The extra points they once received on the national university entrance exam (高考) are being reduced and will soon be eliminated entirely. Judicial leniency has now been replaced with heavy-handed incarceration and reeducation in the name of stability maintenance. And any cultural or religious rights—beyond the tokenistic and voyeuristic—are being slowly hollowed out and replaced with a heavy dose of ‘patriotic education’, ‘inter-ethnic mingling’, and lessons in ‘becoming Chinese’ (Leibold 2016 and 2019).

What unites these policies is their focus on removing ‘minority privileges’ as a way to ensure integration, promote nationalism, and create a more homogeneous society. In this sense, they share much in common with colonial practices that have been tried and tested elsewhere.

The Recognised and the Unrecognised

We can identify two related colonial techniques. One is to deny the existence of subaltern groups. Another is to recognise the existence of these groups, but to bar membership to them. Both techniques create a division between the recognised and unrecognised—between those with and without collective rights.

In Sweden, the ‘reindeer laws’ based Sami identity on participation in reindeer herding, and so Sami who practised agriculture or lived in towns were denied recognition (Axelsson 2010). In the United States, the system of federally recognised tribes denies the existence of certain groups (Ramirez 2007). In Australia, Indigenous groups must be able to show an ongoing connection to their traditional territory to gain access to native title, and in cases where they cannot, their claims are denied (Vincent 2017). In India, the state reduces the over 10,000 languages named by its citizens in the census to just over 100, by imposing arbitrary standards such as a population threshold of 10,000 (Kidwai 2019).

In all these cases, the state aims to avoid meeting its obligations to Indigenous and minority peoples by declaring them nonexistent. In short, they engage in what has been called ‘paper genocide’—the destruction of a people by their exclusion from formal recognition by the state (Deerinwater 2019).

The second-generation ethnic policies, however, do not propose to undertake paper genocide by denying the existence of the 55 formally recognised minority nationalities (少数民族) in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Rather they achieve similar effects by making the distinctiveness of minority nationalities meaningless, by removing the legal significance of this recognised distinction while slowly integrating them into mainstream society and its norms. Therefore, in order to understand the impacts this is likely to have, we can look at the historical experience of groups in China that have undergone paper genocide: those that were refused recognition in the ethnic classification process. These groups, denied recognition by the state, offer a window onto the future of recognised nationalities (民族, minzu) under the second-generation policies.

Victims of Paper Genocide

Non-recognised peoples emerged in the PRC as a result of the ethnic classification process (民族识别) during the 1950s. Rather than a way to negotiate rights and privileges for preexisting groups, this process aimed to establish what the categories of recognition were to be, and then decided what rights, such as regional autonomy, would be delegated to them (Bulag 2019).

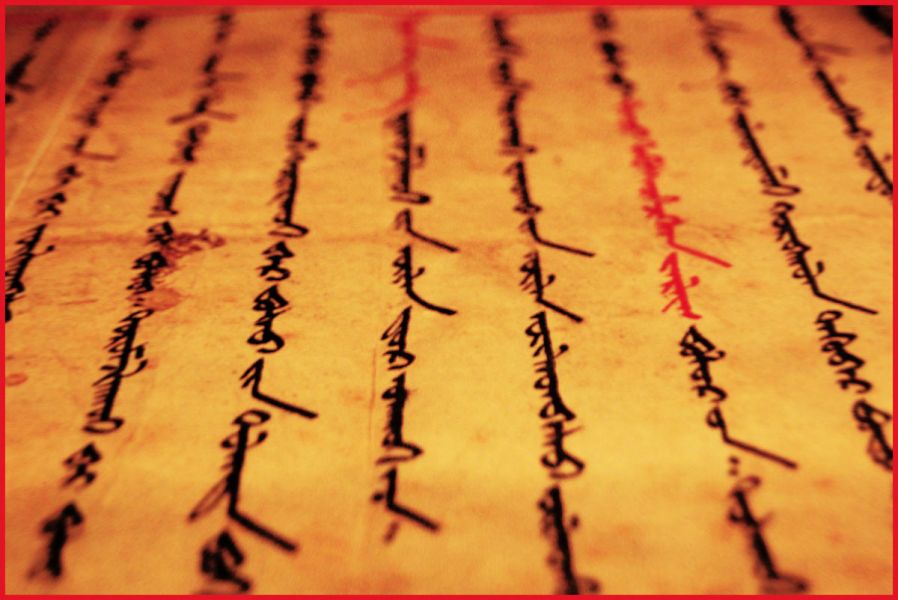

Thomas Mullaney (2011) has described how this process involved both expert testimony and the consent of the classified. In Yunnan, linguists classified the population on the basis of linguistic similarity. Local cadres then worked with representatives of those populations to convince them that they ‘actually’ spoke those languages, highlighting points of similarity across barriers of mutual unintelligibility. Through similar processes of amalgamation, the original 400+ groups initially recognised in the PRC were reduced to the 56 nationalities recognised in China today.

This process involved vast and violent processes of merging and melding, lumping together disparate groups on the basis of their ‘ethnic potential’. Cherished identities were rendered nonexistent. Groups that were caretakers of centuries of collective memory were suddenly obliterated in the eyes of the state and, in order to make their claims legible, were required to represent themselves in the state’s terms—regardless of the language they spoke, identity they professed, customs they practised, and affinities they felt.

Occasionally, the groups that were obliterated in this process resurface to remind the state of their existence. For example, in Sichuan, the Baima people, who are classified as Tibetans, have petitioned to be recognised as a separate nationality (Upton 2000). The authorities refused, and the Baima are now compelled by the state to be Tibetan, and hence must choose between ‘mother tongue education’ in Tibetan, or education in Chinese—neither of which is their own language. Similarly, the Ersu people have petitioned to have their distinct identity recognised and to refuse their classification as Tibetans, and the state refused (Wu 2015). Guizhou is home to some 21 distinct groups who are ‘unclassified’. Yet in 2014, Xi called an end to this game—declaring China would not only have no new minzu groups but that it also needed to actively fuse the existing ones together (Leibold 2014).

Non-recognition and the removal of ‘minority privileges’ have the same effects: they both deny groups their rights to their own cultures, languages, and identities. Non-recognition silences by denying the existence of the group while second-generation ethnic policies recognise the existence of the group, but deny that they should have any specific rights. Both end in the same place: with the denial of collective rights.

What has happened to the unrecognised groups of the PRC since they were stripped of their rights? Although their identities sometimes remain, they have been subordinated to official categories, giving rise to new hybrid terms such as Baima-Tibetans, or semi-official, sub-minzu categories like Mosuo or Chuanqing people (人 ren, rather than minzu) that have no standing in the law. Denied the right to exist, these groups have largely succumbed to the state’s assimilatory pressures.

Among Tibetans, for example, the languages associated with unrecognised groups are all in the process of being eliminated, with most groups shifting towards Chinese, and a few to Tibetan (Roche 2019). More broadly, the refusal to recognise these groups is driving the widespread elimination of languages across the PRC: linguists in China estimate that half the country’s languages are being replaced with either putonghua or languages of recognised minzu (Xu 2013).

On Having Something to Lose

Unrecognised groups in China have never protested the removal of their languages from schools, because their languages have never been used in schools. As the state and its institutions were built around them, these groups and their languages were excluded every step of the way.

Mongols are protesting because they have something to lose. They have an education system and other institutions that recognise and reproduce their language. And they can look to Xinjiang and Tibet to see what happens when these institutions are taken away.

But we should also look to the unrecognised groups of China, and see how paper genocide has led to cultural genocide. What Mongols fear to lose, most languages in China have never been granted. The situation in Inner Mongolia rightly raises concerns about the assimilatory intent of second-generation ethnic policies. The PRC’s unrecognised peoples show us how warranted these fears are, because they have been living with these policies since 1949.