Builders from China: From Third-World Solidarity to Globalised State Capitalism

When thinking about China’s integration with the global economy, the usual landmarks referred to are the ‘Going Global’ (走出去) strategy launched in the late 1990s and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. China’s overseas economic activities before these events tend to be overlooked, as though they did not exist. But as this essay will show, the actual ‘going global’ of Chinese economic actors took place long before these watershed moments. If these important activities have escaped analytical attention, it is because they are not captured by the statistical categories conventionally used to measure international economic activities, such as outward foreign direct investment (OFDI), despite the fact the Chinese authorities routinely document these activities and publish statistics about them.

International contracting (对外承包) is the main activity that has been largely overlooked by external observers. Since the late 1970s, Chinese companies have been hired for overseas projects to provide construction and engineering services, or sometimes as designers, consultants, or operators. In terms of economic accounting, international contracting is a form of trade in services. But in China, it is given the term ‘international economic cooperation’ (对外经济合作) and has been reported alongside OFDI (MofCOM n.d.). The framing as ‘cooperation’ reflects a specific outlook of China’s, which has been shaped by its domestic political and economic context, as will be explained later.

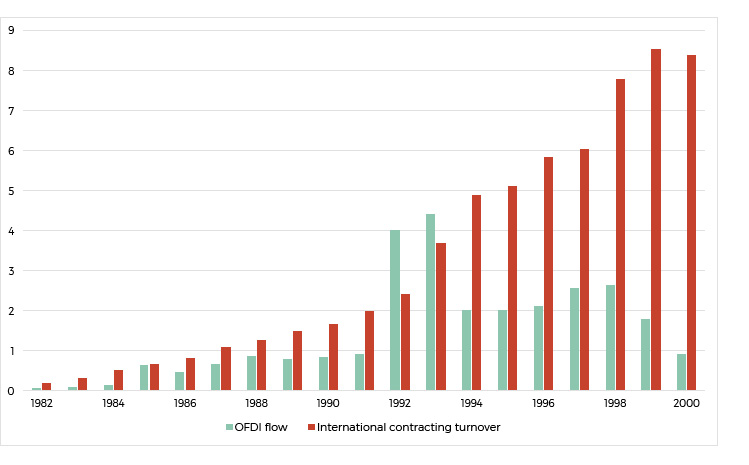

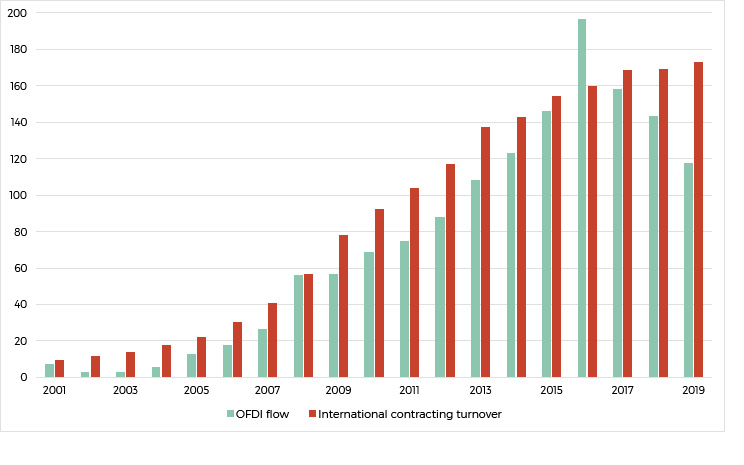

Measured by its volume, international contracting as an overseas economic activity is arguably more important than OFDI. As Figures 1 and 2 show, while both international contracting and OFDI grew dramatically in the past four decades, international contracting enjoyed a substantial lead over OFDI, especially in the pre-2000 period while OFDI started to decline since 2016, international contracting has held steady.

Today, China’s international contracting industry has some of the most globalised companies with the longest histories of overseas operation and the largest numbers of overseas subsidiaries and foreign employees. In 2020, 78 of the world’s 250 largest international contractors were from China (ENR 2021); among them, Chinese contractors received the largest share (25.6 per cent) of revenue in overseas markets—more than 10 percentage points higher than the next country in line, Spain. Chinese companies are particularly dominant in Africa and Asia, taking up 61 per cent and 49 per cent of their international contracting market share in 2020, respectively. Thirteen companies in the construction and engineering sector made it on to the Global Fortune 500 list in 2020, nine of them Chinese (Caifuzhongwen 2021).

International contracting deserves more analytical attention also because it covers most of China’s current overseas infrastructure development—the kind of activities closely associated with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While much policy and media attention is fixed on China’s financing of overseas projects, often neglected is the fact that China is also building these projects. In fact, it is the capacity to build these projects—the engineering prowess demonstrated through such endeavours—that domestic Chinese narratives tend to highlight. ‘Builder’, rather than ‘financier’, is more reflective of the kind of image China seeks to project globally.

In the rest of this essay, I will trace the history of China’s international contracting industry, explaining how it mirrors China’s shifting role in the global economy, from being primarily a labour exporter to a capital and technology exporter, and now aspiring to be a technical standard setter. I will explain why international contracting has been closely intertwined with Chinese diplomacy, and how it epitomises China’s state capitalist economic structure.

From Aid Workers to Labourers

China almost missed out on what was considered the first wave of globalisation of the construction industry: the construction boom in the Middle East in the 1970s. Following the 1973 oil crisis, massive petrodollar incomes in the oil-exporting countries saw them engage in a construction project spending spree. At this time, however, China was caught up in the Cultural Revolution, which repulsed profit-seeking activities both at home and overseas. China turned down a few hiring offers from Kuwait and Iran, on the basis that ‘we are no contractors’ (Liu et al. 1987: 9). Meanwhile, Mao Zedong’s foreign policy required that China present itself as a selfless provider of assistance to the Third World’s infrastructure construction—most famously, the Tanzania–Zambia Railway (TAZARA; see Monson’s and Rudyak’s essays in the present issue)—for which China not only sent engineers and workers to work alongside locals, but also provided grants or interest-free loans (many of which were later forgiven) to finance the costs. The combined effect was that China was starved of foreign exchange while bleeding fiscally; as an impoverished country, it spent 5.88 per cent of its fiscal budget on foreign aid during the period 1971–75 (Sun 1993: 10).

Mao’s death in 1976 opened room for Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders to rethink their resistance to international commerce. As the December 1978 Third Plenum of the CCP’s 11th Congress officially affirmed the centrality of economic development instead of class struggle, three companies were established with a mandate to engage in international contracting: the China State Construction and Engineering Corporation (CSCEC), China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC), and China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), which were under the aegis of the State Construction Commission, Ministry of Railways, and Ministry of Transport, respectively. These companies built on the foreign aid offices previously set up in the respective ministries to coordinate matters related to aid provision, as they were virtually the only ones with any experience in international economic management. They were considered ‘windows’ for their respective sectors to seek overseas contracts. A similar ‘window company’ model was then replicated in the following years in other line ministries such as aviation, hydropower, machinery, petroleum, metallurgical, and chemical industries, as well as in dozens of provinces and municipalities. These companies often shared a suffix of ‘international economic and technological cooperation company’ (国际经济技术合作公司) in their names, and they were given the prerogative to engage in international contracting and trade-related activities. These ministry and regional government–affiliated ‘window companies’ can be understood as a controlled experiment to expose China’s industrial economy to the international market, organised through the state’s grid-like (条块) system of administration.

These companies had a modest start. The CCECC, for example, was founded in 1979 with two loans of RMB1 million and US$30,000 from the Ministry of Railways and Ministry of Foreign Economy and Trade (CCECC 2009). Compared with the other ‘window companies’, CCECC perhaps had the most experience organising domestic resources for overseas engineering projects, given that its predecessor oversaw the construction of TAZARA in the previous decade, which drew manpower and technical input from a total of 43 entities across China (Shen 2009: 96). Indeed, one of the CCP leaders’ motivations to engage in such a demanding project was to showcase China’s engineering capacity and to spur the technological progress of Chinese industries; in Zhou Enlai’s words, ‘implementing foreign aid to promote domestic [development]’ (抓援外, 促国内) (Shen 2009: 153; for the pragmatism in China’s foreign aid in the Maoist era, see also Rudyak’s essay in this issue).

The companies immediately looked to the Middle East for their initial market exploration. Knowing they were already late to the party, they started as subcontractors providing labour for other international companies. CCECC’s first contract, for example, was to supply 400 workers to a Japanese company for a highway project in Iraq in 1979, which was followed by more labour-supply contracts with companies from West Germany, Italy, and Brazil in the next few years. Between 1979 and 1985, CCECC sent more than 20,000 Chinese workers to Iraq alone to fulfill 41 labour contracts (Wang 1996). Such a focus on labour supply characterised the initial business strategies of all ‘window companies’ in the 1980s, as they enjoyed the double advantage of low labour costs and highly disciplined state-organised labour—a result of the fact that, unlike other international migrant workers, the Chinese workers were largely drawn from the state danwei system and were expected to return to their work units—to which their lifelong welfare provision was tied—after the contracts were completed.

While this seems a natural move now, labour contracting was not easily accepted in China back then, as the country was still reeling from the ideological fervour of the previous decades. During the first national conference on international contracting in 1982, concerns were still being voiced that such activities resembled the indentured labour of the ‘old China’ (Liu et al. 1987: 11). It took Hu Yaobang, then General Secretary of the CCP, to affirm the legitimacy of labour contracting in an important speech in 1982 for China to explore participation in the international economy (People’s Daily Online 2007).

Such a context also explained why Chinese policymakers opted for the frame of ‘international economic cooperation’ to encapsulate contracting and other international economic activities, which was meant to invoke a more equal exchange of resources to be distinguished from the deeds of ‘capitalist countries’. As I have explained elsewhere (Zhang 2020), the initial contracting companies built on their experience in Maoist foreign aid projects to continue in subsequent decades as commercial contractors in China’s aid projects (which often took the form of infrastructure projects and public facility construction). In fact, competing for Chinese aid contracts has been a common strategy for the contracting companies to expand into new foreign markets, while the Chinese Government has also explicitly tapped into mechanisms and ties established through foreign aid to promote international contracting as part of its ‘strategy of broadly based foreign trade and economic cooperation’ (大经贸战略), which it started pursuing in the mid-1990s (Ministry of Foreign Economy and Trade et al. 2000). In short, framing these activities as ‘cooperation’ signifies the intertwined relationship between China’s foreign aid and international contracting, and between China’s diplomacy and commercial pursuits. This continues in the era of the BRI.

Becoming ‘National Champions’

While labour contracting proved an easy way to reap profits, from the outset, Chinese policymakers pushed for a greater leveraging role in international contracting to support China’s exports. In the very first national conference on international contracting in 1982, Chinese authorities urged companies to ‘bring out our equipment and materials by all means’ (Liu et al. 1987: 13). This would require Chinese companies to take on more sophisticated contracts that involved responsibilities beyond supplying labour and, to do so, they would need to build their capacity in construction and engineering.

The state was actively guiding this process (Zhang 2021). Starting in the 1990s, policies encouraged leading industrial firms to directly engage in international contracting, and they were no longer required to go through the ‘window companies’ representing their sector to approach foreign clients. State authorities gave large industrial firms priority when granting licences for international contracting (Li 1993), while smaller firms affiliated with lower-level governments (prefecture and county level), as well as non–state-owned firms, were kept from entering this business (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation 1999). State-affiliated engineering design institutes were pushed to commercialise and compete internationally for engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contracts and, to prepare for such undertakings, they were given privileged access to state-invested projects at home (Ministry of Construction 1999). Essentially, the state controlled the level of competition to ensure profit levels for larger firms, most of which were state-owned during the 1990s.

As China prepared to join the WTO, Beijing further elevated international contracting as a strategic sector that must be supported by all levels of government. Six ministerial bodies with authority over China’s economy, trade, foreign affairs, planning, and finance jointly issued a directive in 2000, urging ‘full recognition’ of the importance of international contracting ‘from a political height’. The directive exalted international contracting’s potential to help China become a ‘trading power’, to transfer surplus engineering and construction capacity abroad, to foster homegrown multinational companies, and to improve China’s political and economic ties, especially with developing countries (Ministry of Foreign Economy and Trade et al. 2000). In the following years, a slew of policy measures was put in place to support the sector, particularly financial resources (Zhang 2020: 21). Meanwhile, as China’s state-owned enterprise (SOE) governance reached a new level of institutionalisation with the establishment of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) in 2003, the state gained greater control over the SOE reform process. A wave of SOE consolidation saw the rise of some ‘super’ contractors. To illustrate this trend, one could look at CCECC’s merger with China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC) in 2003, as part of the state-directed SOE restructuring to create stronger enterprises.

As mentioned earlier, CCECC was one of the first three ‘window companies’ established in 1979 to venture into international contracting. Starting off primarily as a labour contractor in the Middle East, it gradually built up its portfolio and developed in-house construction and engineering capacities. In 1995, CCECC achieved a milestone for Chinese international contracting by securing a US$520-million contract to repair one of Nigeria’s railways (Yao 2009). At that time, it was the largest overseas contract won by any Chinese company, which also marked the start of the company’s rise as a leading contractor in the African market. By 2003, CCECC had overseas branches in more than 20 countries and experience of working in more than 40 (CRCC 2004: 377).

By comparison, CRCC was a gargantuan SOE with special significance in the national political economy, but with more limited international exposure. It was previously known as the Construction Headquarters of the Ministry of Railways (铁道部工程指挥部), which itself was formed by absorbing nearly 150,000 former Railway Troops (Cai 2021). During the Maoist era, these soldiers played a big role in the Third Front Campaign, building railways into the country’s inland provinces, but they were demobilised by 1984 as Deng Xiaoping moved to cut China’s military spending (on the Third Front, see Galway’s interview with Meyskens in this issue). The 10 divisions of Railway Troops in various parts of China were then converted into 10 ‘engineering bureaus’ to be administered by the Ministry of Railways. They continued to carry out construction missions for the country’s expanding railway networks, although now as civilians rather than soldiers. As part of China’s 1980s reforms to separate companies from the administrative system, the Construction Headquarters was stripped from the Ministry of Railways and incorporated as CRCC in 1989, and the 10 engineering bureaus became 10 subsidiaries of CRCC. However, in the early 2000s, the CRCC system still appeared less like a corporation and more like a cumbersome administrative hierarchy, with more than 3,000 units structured by bureaucratic rank, and unaccustomed to market competition (CRCC 2003: 62). In 2002, its annual overseas contracting revenue was only about US$100 million (CRCC 2002: 130).

In this context, the merger of CCECC into CRCC was expected to stimulate the latter’s marketisation and internationalisation. Meanwhile, backed up by CRCC’s greater engineering capacity, accumulated through decades of railway construction in China, CCECC could now compete for more technically demanding projects. This strategy seems to have worked. A few years after the merger, CRCC and CCECC were jointly winning record-breaking contracts, including a US$8.3-billion railway project in Nigeria in 2006 (which was later scaled down), a US$2.31-billion highway project in Algeria in 2006, and a US$1.27-billion high-speed railway project in Turkey in 2008 (CRCC 2006, 2008).

These major overseas advances took place against the backdrop of a top-down drive from China’s SOE regulator to ‘go big or go down’. China had a five-year transition period after its accession to the WTO in 2001 to remove entry barriers for foreign investment, and industries including construction were anticipating an influx of foreign competitors after 2006 that could threaten their survival. ‘All sheep are now exposed in front of the lions … We must strengthen ourselves and become a lion ourselves fast. What is “fast”? We have four years to become a strong enterprise,’ CRCC’s Chairman and Party Secretary Li Guorui urged in a 2007 executive meeting, as SASAC gave the deadline of 2010 to become a ‘world-class’ construction company (CRCC 2007: 4). The company needed to demonstrate that it could compete in the global market and had to step up internationalisation. It was also responding to the political leadership’s call for the formation of China’s own multinational companies, given the country’s greater exposure to the global economy (Jiang 2002).

The decades of pushing by the state to develop international contracting as well as SOE restructuring have established a hierarchical ecosystem in this sector. At the top is a small number of central SOE groups that dominate a specific sector: railways (CRCC and China Railway Group), general construction (China State Construction Engineering Corporation), transportation (China Communications Construction Company), electricity (Power Construction Corporation of China, China Energy Engineering Corporation), and metallurgical industry (Metallurgical Corporation of China)—to name some of the largest. These groups can be seen as a reincarnation of the socialist state-run industrial systems, and they continue to control extensive networks of subsidiaries across China that were previously subordinate to the line ministries, in which these gigantic SOE groups used to be part of the administrative structure. Commanding ‘national’ industrial capacity, these major SOE groups are at the forefront of securing the largest overseas contracts, many of them high-profile infrastructure projects financed by Chinese policy banks that are now associated with the BRI. They also represent China’s technological frontier (such as in high-speed railways) and have been exporting Chinese technical standards to overseas projects. The middle tier includes some of the more specialised central SOEs, as well as provincial and municipal SOEs and some private firms, which often work with the top-tier SOEs as minor partners or subcontractors on mega-contracts but may also independently win mid-sized contracts. At the bottom are the even smaller firms, often privately run, which supply labour, materials, and equipment to the larger firms.

Projecting Chinese State Capitalism

Studying the history of the international construction industry from the nineteenth-century British Empire to the postwar expansion of US companies, Linder (1994: 6) shed light on the ‘crucial but neglected historically changing role that multinational construction firms have played as creators of the physical skeleton of the international economy and as agents of the incorporation of the economic periphery into internationalized capital circuits’. Thus, he argues, that multinational construction firms have served to ‘project capitalism’ to countries on the periphery of the international economic system. In this light, the rise of Chinese contractors we are witnessing today is but a repetition of the history of capitalism.

The difference, of course, is that in this current iteration, the Chinese state plays a particularly prominent role in providing the vision for and coordinating the actions of the construction firms. The agents—the construction and engineering firms—have emerged less from market competition than from the state’s top-down ambition to preserve and grow the nation’s industrial system, which is considered a key source of national power. These firms’ approach to overseas markets has been guided by the various structural needs of the Chinese economy, from exporting labour and industrial products in the early years, to obtaining resources as China became the ‘world’s factory’—as seen in the ‘infrastructure for resources’ deals in Africa (Alves 2013)—to facilitating the relocation of China’s excess industrial capacity, and the propagation of Chinese technology and technical standards in more recent years, as seen, for instance, in the construction of overseas industrial zones, telecommunication networks, and railways applying Chinese standards.

The question is, therefore, whether the prominence of the Chinese contractors will soon fade as their national economy moves towards post-industrialisation, as occurred with their US, Japanese, and South Korean predecessors. Or whether, given the vast size of the Chinese economy and uneven development of its regions, China’s industrialisation process will be much prolonged, and therefore will allow the Chinese contractors to have a more sustained impact on the global economic periphery they have been penetrating. In any case, given the close ties between the Chinese contracting industry and the state, they have introduced a different mixture of politics and economics to global capitalism—one that is a source of both intellectual curiosity and controversy.