Mapping the Affective Neighbourhood in Post-Protest Hong Kong

‘Lennon Walls’—that is, public walls covered with post-it notes, posters, and manifestos left by citizens—were a major feature of the protests in Hong Kong during both the Umbrella Movement of 2014 and the Anti–Extradition Law Amendment Bill (ELAB) Movement of 2019. On both occasions, Hong Kong citizens placed hundreds of thousands of post-it notes on all kinds of vertical surfaces throughout the city. Scholars have called these places sites of citizenship, social engagement, and imagination, and even public art (Ku 2019; Valjakka 2020; Ng 2021). But while Lennon Walls such as the one set up at the Hong Kong Government Headquarters in Admiralty in 2014 were a major theatre of protest, these set-ups also mushroomed in more ‘ordinary’ formats elsewhere in the city in 2019. Throughout 2019 and 2020, protest messages were mounted on walls inside a neighbourhood noodle shop, on the pillars of a highway overpass, next to a subway station, and even in the corridors of some public hospitals (Guardian of Hong Kong 2020). Since the enactment of the National Security Law (NSL) in July 2020—as the city was rocked by continuous arrests, court hearings, and detentions without bail—these messages have largely vanished.

By examining the pedestrian spaces once occupied by Lennon Walls, this essay traces the affective tension between life somehow going back to normal for many citizens on the one hand, and the ongoing persecution of dissidents on the other. Looking closely at the changing faces and materials of some pedestrian surfaces, this article first challenges the official narrative that the NSL targets only a small group of prodemocracy leaders, showing instead how the law is radically transforming the spaces, politics, and culture of the city. Second, it locates the politics of crackdown and resistance outside the subjectivity of the rulers or the ruled, the arrests of activists, or the tactics of the protestors. Rather, it focuses on the visual moments and sensual encounters of residents walking through their neighbourhoods, revealing an emergent politics of affect in which the ‘intensities of feeling’—sounds, senses, and other non-verbal dynamics—prevail (Thrift 2004; Massumi 2002). By mapping the affective cityscape, I aim to deepen an understanding of authoritarian politics as embodied in everyday life. I also argue that the government’s efforts to clean up have paradoxically reinforced those ‘intensities of feeling’ the clean-up was supposed to suppress.

Since the enactment of the NSL, the Hong Kong police have charged and imprisoned many prodemocracy leaders, lawyers, scholars, elected councillors, civil society activists, and journalists over their organisation of and participation in banned gatherings and a primary election for the now-postponed Legislative Council election—all of which have been redefined as secessionist activities. The detention and heavy sentencing of some iconic figures—such as Apple Daily’s owner, Jimmy Lai, and Scholarism’s leader Joshua Wong—have made headlines around the world (Wong and Lau 2021; Siu 2021). While these cases have attracted most of the media attention, the government has also locked up thousands of citizens, many of them youngsters, who participated in the protests of 2019 and 2020. Their crimes range from displaying or shouting certain slogans to posting certain news on Facebook, from struggling with the police to being found with a laser pointer or a cutter in their backpack, among many others. Combined with the anti-pandemic gathering ban that began in mid-2020, the NSL effectively ended all rallies, protests, and public gatherings critical of the government (Wong and Cheng 2021).

This is perhaps the first time in the recent history of the city that citizens have seen so many political prosecutions. Behind these arrests and heavy sentencing are Hong Kong’s leaders, who have remained indifferent to the mass exodus of disappointed citizens who have chosen to leave Hong Kong, their homes, stable jobs, and loved ones (Wordie 2021). Chief Executive Carrie Lam claimed ‘the Law has restored social order and brought the city back on the right track’, while other government officials welcomed the NSL, saying it was ushering in a ‘new favourable era’ (SCMP 2021).

With the government-aligned press and political leaders sounding more and more like a propaganda operation, many citizens feel increasingly alienated from the state and question its severe bans on gatherings during the pandemic. The public’s distrust of the government is also reflected in the city’s low vaccination rate and the widespread refusal to download and use the government’s public health tracing app, as people fear these tools will be used for political surveillance. But between the continuous arrests, court hearings, and the plainly false official claims of normalcy and stability, what is happening in the city at the pedestrian level? While the protests and the Lennon Walls have disappeared, have the streets reverted to the grey concrete surfaces they once were?

This essay traces some encounters during and after the protests in the Eastern District of Hong Kong Island, a part of the city I often visit. I have included photos of a pedestrian tunnel, pavements, and elevated highway support pillars that during and after the protests were transformed into major displays of discontent. By showing the ways the government has scraped away or covered over all protest messages, post-it notes, and graffiti, and the new kind of visual and sensual experiences residents like me have had, this essay attends to that affective everyday realm that is not often captured by media headlines.

Three Incidents

Some brief history is useful here. The Eastern District of Hong Kong has always been a rather quiet residential area, around 20 minutes east of the Central Business District (CBD) by bus or subway. It is home to about half a million ageing people and middle-class families. When Carrie Lam’s administration announced its intention to push forward with the ELAB despite the fact two million citizens had joined rallies against it in June 2019, many protestors felt desperate and decided to adopt a new strategy of decentralising the protest movement to as many residential areas as possible. Dubbed ‘blossoming in every district’

(區區開花), the strategy was meant to reach out to more citizens and avoid focusing exclusively on the heavily policed CBD, where the Government Headquarters is and where the Occupy Central Movement of 2014 and many protests in the 2019 Anti-ELAB Movement concentrated. Following this strategic adjustment, protestors started to create roadblocks, organise handholding human-chain demonstrations, and set up Lennon Walls in multiple residential districts.

Three protest-related incidents in the Eastern District neighbourhoods of North Point, Taikoo, and Sai Wan Ho provide us with some insight into the affective politics of today’s Hong Kong. The first was on 5 August 2019 when a group of men in white shirts took up batons to beat protestors passing through North Point. The attackers were allegedly linked to the Fujianese Fellows Association, which has close connections with pro-Beijing forces. Protestors felt the police did not protect them from the attacks and left them to defend themselves (Ramsay 2019). The second incident was on 11 August 2019, when a team of riot police fired teargas inside the Taikoo subway station to stop protestors. In the encounter, police were seen pushing over protestors on a moving elevator, almost creating a stampede (Siu and Zhang 2019). The third incident, on 1 November 2019 in Sai Wan Ho, was one of the major escalations of 2019: a young protestor who was trying to set up a roadblock at a major crossroads outside the Sai Wan Ho subway station was shot in the stomach by a police officer (Lau and Cheung 2019).

These three events stirred emotions in the normally quiet, comfortable middle-class residential areas of Eastern District. They brought triad and police violence, roadblocks, anti-government slogans, and teargas on to the doorsteps of ordinary residents, including mothers with babies, elders in wheelchairs, and nuclear families trying to find a place to eat in the neighbourhood. For many residents who did not normally join the protests, this was their first experience of breathing teargas, feeling the acid in their throats, getting skin rashes, witnessing violent arrests, and hearing gunshots. All were visceral and painful experiences. One would therefore assume the government would want to quickly erase the memory of such events and alleviate residents’ anxiety by quickly returning things to normal, and that the clean-up campaign would at least try to make people forget the most nightmarish details of the protest. Surprisingly, the result of the clean-up effort was rather different.

From Lennon Walls to Government Murals

At the height of the Anti-ELAB Movement, public surfaces in residential neighbourhoods were covered in all kinds of messages, posters, and notices. On the pillar in Eastern District depicted in Figures 1 and 2, the post-it notes were covered in protective plastic. Later, satirical cartoons and slogans printed on A4 sheets were added. One of the biggest slogans—the one that can be read in simplified Chinese characters on white paper at the bottom of the pillar—reads: ‘Wherever there is repression, there is resistance’, which is a quote from Mao Zedong. Many posters were torn down, perhaps by residents who held a different opinion about the movement. At the height of the protests, in Eastern District, there were at least a dozen such pillars or walls of protest. These installations lasted on and off from August 2019 to July 2020, when the NSL was enacted. Many pillars then assumed a new face, as the government had them painted with various slogans and images related to traffic safety, such as ‘Cross with the green light’ and ‘Watch out for the elders’. Though colourful, the illustrations, characters, and layout were often not attractive. Whenever I walked towards the pillar in Figures 1 and 2, my eyes often focused on the two rectangular outlines above the mural, and I wondered why they had not been entirely cleaned or covered.

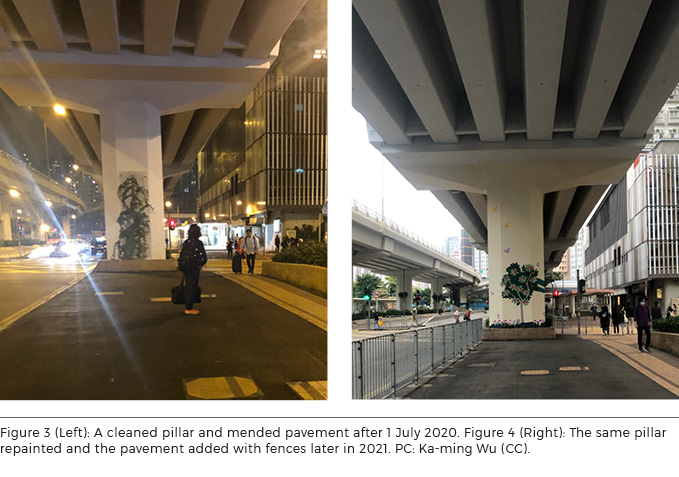

After the enactment of the NSL, more clean-up campaigns were launched across the city. Figures 3 and 4 show another support pillar close to the previous one. In the wake of the NSL in 2020, the surface of the pillar was cleaned and it as painted white, even though wild vine continued to grow on one side. Figure 4 shows the same pillar in 2021. The wild vine was removed and a tree and butterflies were painted on the surface of the column. The photos also show the extent to which the damaged pavement was mended. The shooting of the young protestor by the police outside the Sai Wan Ho subway station outraged many. Some protestors dug up this pavement and used the paving bricks to establish roadblocks, which were then quickly cleared. Even though these roadblocks were short-lived, for several months in early 2020, residents had to walk on dirt and cobbles where the pavements had been vandalised. By the time the photo in Figure 3 was taken, the footpath had been re-laid with black concrete—a big contrast with the original red bricks. The repair work, however, was not done properly. The pavement was no longer level and, for a long time, the repainted white pillar contrasted strongly with the ugly mended pavement. While perhaps not everyone would be reminded of the shooting, the bodies of the injured, and the battles that took place in the area, it was nonetheless awkward for anyone who walked there. In fact, one sometimes had to focus on their feet to avoid tripping; residents using strollers, wheelchairs, or shopping carts would feel the bumps even more.

The painting of murals on pillars that had been covered with protest messages started in the summer of 2021 in many areas of the Eastern and other districts. Most of the artwork depicted natural themes such as trees, flowers, and butterflies, replacing the traffic safety slogans that had been initially used as a substitute for the protestors’ messages. These murals have changed citizens’ spatial perspectives of their own neighbourhood. Before the Lennon Walls, passers-by barely noticed these highway pillars, which were dusty, dull, and merely functional. The Lennon Walls drew residents to look closer at the messages. The new murals, instead, draw one’s eyes up, offering people a vertical perspective of how the neighbourhood has been surrounded by elevated highways and bridges. The murals brighten and generally beautify the walkways under the highway, yet somehow they create a stronger tension between the repainted surfaces of the community and the daily news of trials and arrests. The government likely expected the murals to deter graffiti, and make vandalising more difficult, but this also raises the question of why the previous safety messages were erased so quickly.

As mentioned, Lennon Walls appeared in different settings. The walls of the pedestrian tunnel in Eastern District pictured in Figure 6 were previously covered in thousands of protest messages. There were multiple clean-up efforts, none of which was successful, as graffiti and protest slogans reappeared after each paint-over. The government eventually came up with a kind of wall covering similar to a white board. Mounted over the concrete tunnel wall, this ‘wallpaper’ with its pattern of white flowers on a blue background repels most types of oil paint. Walking through this tunnel is a rather dizzying experience and it is difficult not to wonder what lies underneath. One can also see the cut marks left by sharp tools. This picture was taken in July 2021, two years after civilians were indiscriminately attacked by triads in the Yuen Long subway station on 21 July 2019. The number 721, representing 21 July, can be seen spraypainted on the ground to avoid the paint-resistant wallpaper. This was wiped clean a few days later.

Affective Afterlives

A cultural studies perspective of Hong Kong after the protests would probably identify petty sabotage, ambiguous graffiti, online boycotts, and satirical writings as windows of potential contestations and continuing resistance when open opposition is no longer allowed. One could also link these small acts to the ‘infrapolitics’ James Scott (2012: 113) brilliantly defined as the ‘prevailing genre of day-to-day politics for most of the worlds’ disenfranchised, for those living in autocratic settings, for the peasantry, and for those living as subordinates in patriarchal families’.

By concentrating on the affective realm beyond the protest movement, and examining changing pedestrian surfaces, I have focused on bodily sensations and the ways they interact with the changing visual and material surfaces of the neighbourhood. I have observed the ways pedestrians hop over rain puddles formed in the cracks where new black concrete meets old red paving bricks. I have paid attention to the feelings of pedestrians walking through a tunnel of shiny flowery wallpaper trying to convey the message that nothing has happened. I have shown the mixed feelings a pedestrian may experience when they see traffic safety messages in ugly images, as well as their suspicion and uncertainty when they see new art murals with nature motifs under the elevated highway.

This essay maps affect—that is, the deeply sensual, visual, and bodily experiences of walking through and feeling the changing materiality of a neighbourhood after the protests, the clean-up, and now the beautification campaigns. I have shown the government’s efforts to deploy various kinds of material coverings, official messages, and even artwork to erase evidence of the protests from urban surfaces. The government might hope these efforts will ideologically restructure ‘the material interactions of things’ and accordingly ‘interpellate the new citizen subjects’ (Massumi 2002: 1–2), but the results have been mixed at best. By bringing everyday matter, the pedestrian body, sensation, and affect to the picture, I have attempted to complicate our understanding of the effects of ideological apparatus and of the relationship between power and culture, going beyond an understanding of affective politics in today’s Hong Kong as a simple dialectic between political crackdown and resistance.

I argue that the state’s constant efforts to clean up have paradoxically reinforced those ‘intensities of feeling’ the clean-up was supposed to suppress. Apprehension about the reappearance of protest messages is ironically sustaining—and even reinforcing—the affectivities of the protests. To many ordinary citizens—including those who did not agree with the protest movement—seeing and feeling the rapidly changing material faces of their neighbourhoods and walking on the repaired pavements can be an intensively sensual experience. It is about coming to terms with the realisation there is no going back to normal in this ‘new favourable era’.