A Conversation about Futurity, Critique, and Political Imagination

This discussion is a dialogue about changes in how we, and others, have approached China and futurity. It has two movements: 1) A Conversation about Futures Past, and 2) Five Propositions on the Future Perfect. We begin with a conversation about some of the scholarly and popular discourses that framed our understandings of China and the future in the post-reform period, especially from the late 1990s until the start of the Xi Jinping era (c. 2012). We then reflect on how we have responded to these issues in our own work, including Jenny’s A Landscape of Travel: The Work of Tourism in Rural Ethnic China (University of Washington Press, 2014) and Joshua’s Underglobalization: Beijing’s Media Urbanism and the Chimera of Legitimacy (Duke University Press, 2020). In the second part, we turn our attention to the present implications and limits of futurity as a lens for critique and political imagination in China and globally.

Section I: A Conversation about Futures Past

Joshua Neves: One of the ways we have been talking about China and futurity is as part of a shift from prior understandings of socialist or even reform-era China that focused on (or at least desired to know) what was happening in the country, to more recent discourses that emphasise what China is doing to the world (including the current fascination with the Chinese Dream and the Belt and Road Initiative [BRI], among many others). The latter, of course, is tied up with China’s mushrooming global significance in the 2000s. Before returning to this theme, I thought we could start by discussing the recent history of futurity in and about the People’s Republic of China (PRC), especially as it regards the PRC’s ‘re-emergence’ on the world stage in the late 1990s and the start of our graduate work in the early 2000s. In your memory, what were the significant events or imaginaries during this period? What images or aspirations held sway? In short, what did it mean to interrogate China’s future a generation ago?

Jenny Chio: In the 1980s and post-Tiananmen 1990s, the burning question seemed to be: ‘What will the future look like in (or for) China?’ At that time, the future, a globally shared future, was expected to radically change China. But after the PRC’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, after the Beijing Olympics of 2008, and in the midst of Xi Jinping’s never-ending China Dream, the question now seems to be: ‘What will China do to/for the future?’ Now China is expected to radically change the future—or, as politicians might say, ‘our’ future. So, the subject of the future, or more precisely the subject affected by the future, has shifted entirely, from ‘China’ as a bounded cultural-political space to ‘the world’. What this means in practice is that the object of my study increasingly seems no longer to be ‘China’ as a sociocultural morass/milieu but rather something, somewhere, or someone in the world and the impact of China on this object, place, or person.

But when I think back to where I was and what I was doing in the early 2000s, I was mostly trying to imagine what rural China’s future was amid the country’s urbanisation push. From the perspective of the countryside, the city was the future. For villages, the path to the future was paved by urbanisation (城市化), and this was pretty much taken as a given in policy and in practice. Of course, this ignored the question of what the future should look like from, in, or for the city.

That is where your work comes in, for me at least. What were you reading in graduate school? What did these books say about the past and future of China?

JN: It is important that you bring up rural China, which has been the consistent focus of your work, because this also seems to be one of the areas in current research and cultural politics that has re-emerged as a central theme in future-China debates. From popular books like Blockchain Chicken Farm (Wang 2020) to engagements with state violence in Xinjiang to peripheral infrastructure and extraction economies (including the BRI), and so much more, there is a sense that much of what matters now is taking place well beyond the highly visible coastal cities and so-called Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities. This is certainly one place where the dominant thread of anglophone academic research of the early 2000s is being inverted. But you are certainly right that at the start of the millennium, urban futures were central to China scholarship and popular imaginaries. Here I have in mind a range of works in media and cultural studies (Abbas 1997; Dai 2002; Pickowitz and Zhang 2006; Rofel 2007; Braester 2010; Visser 2010) that centred on urbanisation, displacement, cultural politics, and the basic premise that China’s urban explosion was globally significant. Indeed, it was widely seen as announcing the future as urban. As a graduate student interested in cinema and the city, I was fascinated by Wu Hung’s personal and art historical portrait, Remaking Beijing (2005), and Zhang Zhen’s edited The Urban Generation (2007), among similar works across the disciplines. Like other scholars at the time, both authors focused on the traumatic speed and scale of transformation in recent decades, as well as the social and cultural responses to inhabiting monumental changes, including the vibrant media cultures and art and activist scenes that were then taking root. These studies were of course countered by a lot of high-flying and often dystopian rhetoric in journalistic and foreign relations discourse, including popular anxieties about The Coming Collapse of China (Chang 2001) or When China Rules the World (Jacques 2009), among countless others.

In short, the massive scale of urbanisation in China from the late 1990s was experienced as a world historical event that shored up new (and old) imaginaries as if overnight. It was, after all, a repetition of previous developmental bursts (like the Ten Great Buildings 十大建筑 project of 1959, which sought to transform the capital city to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the PRC). I still remember how abruptly China’s economic rise reshaped understandings of globalisation in the North Atlantic; or at least how it was routinely narrated this way. It seemed as though at one moment all the orientalist fears and hopes were tethered to Japan or even South Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong, and then suddenly it was the PRC, often alongside India, which dominated discussions of ‘our’ future. But the futurities envisioned from the vantage of the city in this period were at once familiar and provisional. For many, inside and outside China, this sense of possibility was double-edged. On the one hand, it led to celebrations of democratic potential and emergent public spheres, new qualities of life, and the integration of China into the world economy; on the other hand, it raised concerns about what constituted the ‘Chinese characteristics’ (中国特色) of this future, especially in relation to the Party-State apparatus, a massive floating population (流动人口), burgeoning income inequality, environmental degradation, breakdown in social supports, etcetera. Pertinent to our discussion is the simple fact that urban futures in this period were often visual promises. Urban plans, architectural renderings, sloganeering billboards, and futuristic videos literally scaffolded cities that had been turned into massive demolition and construction sites. There was a very real disjuncture between the life-worlds imagined by these futuristic images and the street-level experience of cities like Beijing, not to mention hundreds of lesser documented cities throughout the country.

Given that your work in this period centred on the rural, I am curious to know what the important ideas and debates were for you and how they differ from urban projections? Do you see this as a matter of perspective—I was in Beijing and the dense coastal corridor, you were in the villages of Upper Jidao and Ping’an—or was this a deliberate focus on rural futures?

JC: The defining popular book that strikes me from the early 2000s has to be Peter Hessler’s River Town (2001). I recall that in every banana pancake–serving cafe I went to in China, English-speaking people were talking about this book. It mirrored what I think foreigners wanted to experience in China, but at the same time it was a reminder of just how foreign China was (or seemed to be). And likely because it was set in a relatively unknown, small city (Fuling, now part of Chongqing municipality), Hessler’s narrative encapsulated how the past and the future of the Chinese people were imagined: somewhat marginal, still largely ‘earthbound’ (an imagination shaped by Fei Xiaotong’s seminal ethnography of rural Yunnan in the years before 1949), full of struggles, and dependent on the largesse of the Chinese State and well-meaning foreigners.

These characteristics were also embedded in mainstream discourses about ‘rural China’ and China more broadly at the time, which can explain why the Chinese State under president and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) general secretary Hu Jintao and premier Wen Jiabao in the early 2000s was so invested in solving the so-called three rural issues (三农问题), referring to peasants (农民), agriculture (农业), and rural villages (农村). When I started graduate school in 2003, one big question with which we China social scientists (at the University of California Berkeley at least) occupied ourselves was the rural–urban divide. The 200 million–plus rural Chinese migrant labourers moving throughout the country were an indicator, so it was thought, of the country’s future—simultaneously celebrated as sign of the country’s economic growth potential and fretted over in terms of the perceived socioeconomic problems that could emerge from so many rural Chinese being, due to the hukou system, ‘out of place’. I would argue that the overwhelming question, conceptually, was and remains: where and how do rural Chinese fit into the imagined, and desired, urban future of China? I am thinking of Solinger (1999), Zhang (2001), and Murphy (2002) on rural migrant labourers, but also Schein (2000), whose influential theorisation of ‘internal orientalism’ helped shape understandings of how gender and ethnic differences inform the cultural politics of the rural–urban divide.

Thus, even as China was leaping into global markets and pouring money into urban growth in the early 2000s, it had not quite ‘arrived’ in global modernity, apparently, because it was still burdened by the rural. This self-positioning as just on the ‘edge’ of global modernity was likewise reinforced in the acronym ‘BRIC’ that was coined around the same time in a report published by Goldman Sachs (O’Neill 2001). Referring to the ‘developing’ economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China, this semantic grouping locates these countries as somehow not quite or not yet central to global geopolitics—a position the Chinese State strategically adopts as needed to justify its own exceptionalism. When I think now about how I imagined studying China’s future as a graduate student nearly 20 years ago, I realise that the task with which I was so compelled—namely, trying to understand the various components of Chinese society rather than trying to understand ‘China’ as a whole—is now impossible (perhaps impossible again). I do not mean this in a cynical way, but rather to suggest that it is, in part, the result of contemporary twenty-first-century geopolitics. If the goal now is to understand China’s role in the future of—fill in the blank here (The world? The United States? Africa? The Asia-Pacific?)—then China is treated, again, as a singularity. This, I honestly believe, is what the current Chinese leadership under Xi Jinping wants, which is for the world to stop peeking behind the curtain, so to speak, and to just focus on the main performance.

JN: Your last point is important because the way we framed this issue at the start of our conversation was that the question of what China is doing to the world primarily mattered to—or was even determined by—Euro-American institutions, knowledge-making, and aims. But as you suggest, one of the key problems here is that a dominant understanding of or approach to China and futurity has emerged, and it seems to serve a wide range of discrepant interests. The distinction between ‘China and the West’, among other popular and problematic framings, obviously fails to capture this complexity, but the point is that this bounded ‘China’ is being reproduced, for different ends, by officials, economists, and experts of various stripes. One of the important shifts that jumps out at me, for example, is that the openness that pervaded earlier imaginings of the future—regardless of their accuracy—is now shuttered, replaced with a future that is seen as closed, predictable, or fated (as with the outcome of the Twentieth National Congress of the CCP in late 2022). This is obviously a problem and constitutes one of the limits of futurity politics to which we should return later in the discussion, especially as I am not convinced that area-studies-as-usual (and the question of what is happening in a determined place) is up to the challenge.

I am also struck by your framing of rural modernity as central to, even if largely ignored by, the developmental aspirations of the period (beyond, that is, urbanisation as a preordained telos). I struggled with a similar problem related to China’s transformations in the 2000s. Only rather than turning to subnational differences—rural, ethnic, autonomous zones, etcetera—I was thinking about regional or transnational cosmologies as a way to contest ideas about China’s singularity (whether of people, cultural politics, governance, encounters with globalisation, colonial and imperial legacies, etcetera). This was no doubt influenced by robust discussions in inter-Asian cultural studies, as well as a wide range of scholars dealing with what felt like similar problems in Argentina, India, Nigeria, Poland, Singapore, Taiwan, and other postcolonial, postcommunist, or Global South contexts. South Asia, in particular, became an important sounding board for me in trying to ascertain what are, on the one hand, globalising tendencies or problems, and what remains specific to China’s ‘post-socialist’ transformation, on the other. In the work of Partha Chatterjee, Swati Chattopadhay, Bishnupriya Ghosh, Ranajit Guha, Lawrence Liang, Bhaskar Sarkar, among many others, I found a body of social and political theory that was very helpful in refusing the singular and ethno-nationalist visions you described above—visions that are only becoming more ubiquitous now—precisely because of their value for thinking about resonant problems in the PRC, and often in fresh ways.

But let us return to the question you posed about researching China.

JC: When I said earlier that I think the Chinese State wants us—meaning foreign academics and researchers—to stop peeking behind the curtain, I also implicated myself. After all, the more I have become immersed in China studies, the more I have fallen into a reliance on what Gail Hershatter (2014) calls ‘campaign time’—my thinking about China orients itself increasingly along the major national campaigns and/or slogans, from Open Up the West (西部大开发), to Construct a New Socialist Countryside (建设社会主义新农村), to Harmonious Society (和谐社会), to the China Dream (中国梦), now to the BRI (一带一路). And even just listing these campaigns by name makes apparent how the object of the future has shifted for and in China.

A shorthand for everything I have been saying might be ‘China beyond China’. In other words, the quality of the future that is at stake is no longer understandable or analysable from just within China’s political boundaries (if it ever was; see also Franceschini and Loubere 2022). But how is this more, or less, than mere globality/globalisation? Where is China’s future? Maybe a concrete way to think about it is through the exodus of Chinese intellectuals over the past decade, in the Xi era, and how this differs from the exodus that happened in the early 1980s, around 1989, and from Hong Kong around the handover in 1997? It is as though the China Dream has pushed a certain class of people out of the country for opposing reasons: artists and activists who no longer see future China as a viable place but also young, motivated, and economically ambitious Chinese students for whom (as a result, no doubt, of their relative socioeconomic privilege) the where of the future feels wide open. Their futures could be in the United States, China, or any number of places.

Where has this situated you and your work? How did your turn to South Asia build on your thinking through China, or Beijing specifically, and where do you see the future of your research on China?

JN: These examples certainly resonate with me. The China beyond China framing, for instance, reminds me of something I tried to formulate in Underglobalization, which I sometimes describe as being about the space between China and the world. I am also struck by the example of the recent exodus of people from China, including, as you suggest, those fleeing what feels like a hopeless future, on the one hand, and the growing numbers of students, professionals, tourists, etcetera, who see the world as a place of opportunity, adventure, and self-realisation, on the other. This is hardly specific to China, but it does have specific dimensions that matter to our conversation about the future as a political subject or stake. The consolidation of China’s current leadership and its place in the world system, while certainly experienced as a point of pride and economic opportunity for many, has also been tied to a deep cultural depression. This (too simple) dichotomy underscores another basic aspect about futurity. As your examples indicate, the where of China’s future also implies a who—that is, who gets to imagine social and political futures? And for whom are these schemas narrowing, pedagogical, or harmful? We talked about this earlier regarding the problem of futurity as a singular rather than plural configuration. But it is also more than that.

One way that I have approached this question of where or who is by tracing shared rather than divergent histories (of the future). For instance, while China and India are often presented as offering opposing futures for the Global South—and here I am thinking of the exoticising images of dragons and tigers that dotted the covers of magazines like The Economist—I have instead been fascinated by just how much their struggles with development, legitimacy, and globalisation coincide. In this, I was certainly inspired by the postcolonial studies scholars with whom I worked at the University of California Santa Barbara. While that field has been much critiqued for its limitations, I still feel strongly about its capacity for a kind of global or multi-sited critique that is too often absent in ‘area’ studies. I recall reading Ravi Sundaram’s Pirate Modernity: Delhi’s Media Urbanism (2010), to take one example, and thinking it was in many important respects about Beijing. It starts by describing how multiple generations of urban and social planning regimes—colonial, national, global—had not only reshaped the city of Delhi but also continuously failed to meet the needs of the local population. The old masterplans, once built, were soon in shambles. This is perhaps a familiar point, but it matters because it emphasises how futurity has been repeatedly employed as a modernisation technique. And while it would be wrong to evacuate futurity discourse entirely of its promise, it is equally misguided to not underscore the relationship between futurity and power. The future, at least in the social and political senses at issue here, operates at scale—indeed, it produces it. So, rather than focusing on established differences, I was also interested in what comes into view when we emphasise instead the shared and ongoing encounters with colonial and imperial forms under globalisation. There is a lot to unpack in such a statement but the simple point for this conversation is that the endemic clash-of-civilisation mode of critique and futurity (that is, the United States versus China, West versus East) stands in the way of alternative understandings or futurings. In this sense, I found that starting from Global South cities, popular media, and politics was a useful way to map geopolitical formations both below the nation-state (subnational) and beyond it (transnational). These actually existing communities and social infrastructures, rather than WTO geographies, could serve as the basis for rethinking the category of futurity itself.

In my book, I take up this problem through the portmanteau word ‘underglobalisation’ (a term that combines ideas about underdevelopment and globalisation). Globalisation is still a dominant blueprint for the future of the world system, even if it is increasingly challenged by, say, China and Russia’s current ‘no limits’ partnership, among others. The point about present forms of underdevelopment, on the other hand, is that globalisation projects consistently obscure the fact that they require inequality as a precondition (rather than inequity being an accidental outcome). So, I wanted to understand how this inequality ‘showed up’ in official claims and ideas about development and the future. One way it showed up was in proliferating discourses about piracy, fakes, imitation, counterfeit culture, technology transfer, and even examples like the former category of children born without permission under the One-Child Policy (超生). These charges were, to my mind, symptomatic of a wide range of important issues. But they also tended to inhibit our understanding of illicit culture. Why, for example, were so many people talking about intellectual property violations rather than the proliferation of illegality itself—of illegal ways of life? This has everything to do with the power of futurity.

I am leaving a lot to the side here, but one ramification of this is the recognition that contemporary global dynamics are increasingly shaped by tensions between legality and legitimacy. From informal media and counterfeit medicine to migrant workers and illegal housing, more and more people live without legal rights and protections. The question is: What happens when legal contracts and imaginaries—including rights, petitions (信访), civil society, and citizenship—fail or become dangerous? And on what grounds are new political relationships claimed and sustained? My interest in the book is to look at the ways that media forms and practices participate in a kind of dissensual future-making in which those marginalised by formal development processes find ways to inhabit the present and establish their own claims on the hereafter. This potentiality offers another way to understand the future as a political form, in part by insisting on how future-making is deeply embedded in the present. My current research builds on this work but shifts its attention to problems of overdevelopment as one of the core models, and thus political challenges, of this present.

The interest in what development obscures and how it fails certain groups of people has been one of our shared projects over the past decade or so. How do you see A Landscape of Travel, alongside your more recent work, in relation to these concerns, including your own engagement with film and video? And how does the view from rural and ethnic China help us to understand—or perhaps change our understanding of—the question of China and futurity today?

JC: I have yet to decide whether A Landscape of Travel is about tourism development or rural development in China. In many ways, the semantics do not matter much because the government policies and investments that arrived in villages like Upper Jidao and Ping’an in the early years of the twenty-first century collapsed the two; but in other critical ways—as I hope my work from this project shows—it was precisely the privileging of tourism over rural development that caused some of the most contentious conflicts and deep disappointments for village residents. The fundamental reason behind such disappointing development was that tourism development invariably centres on the figure of the tourist (personified by the urban or cosmopolitan traveller), so tourism development in rural villages was really aimed at urban Chinese and worldly cosmopolitans. If it really was rural development, on the other hand, the projects would have (ideally) centred on the rural (personified by the peasant/villager).

But what matters most here is the fact that development in whatever shape or form is fundamentally about the future; the temporal thrust of development is inherently future-facing. My interest in ethnic minority lives and rural experiences in China, therefore, remains shaped by an interest in not only how these marginalised communities make space for themselves (and are made to have a place) in China as a nation-state, but also how development as a discourse and a process engenders and necessitates certain actions in the present that are expressly for the future. Rural China, it seems, bears the weight of the future in so many ways: in the past, as the source of and motivation for the revolution; in the present, as the place where urbanites find respite and politicians see extractive profits; and in the future, as the sign that the nation has ‘made it’ when rural communities are firmly ensconced in a ‘moderately prosperous society’ (小康社会).

While my research on tourism is situated in the very recent past and the almost-present, even as much ethnic minority tourism is premised on romantic and deliberately atemporal ‘cultural heritage past’, working with documentary film and video in China has prompted me to think more deeply about media, memory, and imaginable futures. The production of representations involves the enfolding of past, present, and future. Xiaobing Tang’s 2015 study of what he dubs the emergence of a ‘socialist visual culture’ in China provides a detailed and specific analysis of how the imagination and the depiction, in terms of the choice of both artistic medium (woodblock prints, New Year’s paintings, oil, charcoal) and content (the typology of rural subjects, from landlords and peasants to soldiers and workers), of rural China as China’s future preoccupied artists in the early years of the PRC. The point was for the art to simultaneously uphold the work of the revolution in the present and its vision of a utopian future. But Jie Li’s expansive book-as-museum (2020) reminds me that memory itself is a device of the future: looking backwards to remember how the future used to be imagined and forwards to imagine what the future might want to remember.

Perhaps more ethnographically, I think a lot now about how documentary practices in China, especially the rural, small, and localised videos in minority regions on which I have focused the most, are best understood as a device for the future to remember the present. Tibetan students in a videomaking class are implored by their teachers to record Tibetan life, so they go off and make films about riding motorcycles through the grasslands or their friends haggling with Han Chinese tourists over the price of a horseback ride; Miao videographers record (and now livestream) bullfights between water buffaloes from Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Guangxi (see Chio 2018). These videos gesture, coyly and indirectly, at a future viewing subject, suggesting that even if you do not think these topics matter, they are memorable. What might these twenty-first-century media objects reveal if/when juxtaposed against the ethnographic films produced by Chinese social scientists in the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1980s as part of the Chinese State’s Ethnic Classification Project (民族识别, a national research project that determined which ethnic groups would be officially recognised)? In the latter films, it was the nation’s future at stake; in the former, contemporary videos, whose future is being imagined is less straightforward. ‘China’ fades into the background of a documentary film made by a Tibetan pastoralist about the multiple uses of yak dung (Lanzhe 2011); the ‘nation’ that appears and is celebrated in a Miao festival video looks, sounds, and moves as a mass, an intensely crowded gathering of Miao celebrants (Chio 2019).

One hypothetical question for us both might be: Can we imagine a future that is not disappointing, to someone—whether to the Chinese State, segments of the Chinese citizenry, or ‘the world’ around China (Sinophone and non-Sinophone alike)? It is an unfair question to ask, but I pose it critically and ironically in terms of formulating new directions for thinking through futurity in and of China.

Section II: Five Propositions on the Future Perfect

Making claims about the future does important cultural and political work. And writing now as scholars critical of the future of futurity, we want to emphasise this longstanding function—that is, futurity’s governmental, developmental, and aspirational operations, among others—and offer a set of modest, provisional, and conjunctural speculations situated in and targeted at the present. It is easy enough to acknowledge an analytical misstep after the fact, especially when it comes to speculating about what is to come. But futurity—the quality of being of or in the future—is tantalising in its seemingly infinite possibilities of imagining what will have been, especially when we temporally locate ourselves in a future beyond the future that is being conceived.

No future is ever entirely open-ended, unstructured, or unbounded by the present, let alone the past. Below are five propositions on futurity, critique, and the political imagination in China. We view them as starting points and points of contention or interrogation, in acknowledgement of our own blind spots and limitations. The aim is less to speculate about what will have happened in the future and more to recalibrate futurity as a tool for critique or analysis.

1. 现实是过去的未来 / Reality is the past of the future. Challenging the retrospective framing of the present remains one of the crucial tasks associated with remaking futurity.

We borrow this phrase from the title of Huang Weikai’s 2009 eponymous documentary to (re)operationalise futurity for the present conjuncture. As the film’s English title, Disorder, also signals, orderly or normative futures act to pathologise, erase, or relocate present realities and histories. These occlusions now constitute a kind of common sense: the future perfect, which is to say they limit the social and political imagination in troubling ways. To start from the idea that ‘Reality is the past of the future’ is to at once underscore how futurity operates as a world-building technology and to insist that much of what constitutes tactical future-making for people around the world exceeds this retroactive image.

2. The political imagination of the future is fundamentally visual or mediated. Moreover, this futurity is constituted by audiovisual constructions that take place in the present.

China today is a society based on spectacle as much as it was in the era of High Socialism. The material, tangible forms of audiovisual futurity that adorn China’s cities and villages, from digital facades and billboards to screen-printed plastic fencing, surveillance cameras, and ubiquitous smartphones, demand conceptual flexibility to analyse how the politics of the present comes into being. This is because state-sanctioned sounds and images—not unlike Hershatter’s ‘campaign time’—oversaturate both popular and scholarly receptions of the future. And the opposite is also true: small tears in these visual repertoires come to stand in for popular will. Against these and similar preoccupations, we want to suggest that the present requires both a renewed attention to official visions of the future—which are too often taken as static or known—as well as modes of analysis and critique that look below or beyond established questions about discourse, image, or plan. In other words, while we know that new technologies and visual projections readily change their shape or quickly become disappointing, even anachronistic, they continue to play the part of the subject of history (when it comes to the future). As such, they prevent us from seeing or imagining otherwise.

3. The habitual focus on political leaders and the nation-state occludes the deep collaborations between antagonistic states (including so-called authoritarian states and democracies) and transnational state–market ventures. Futurity emerges in this underbelly just as much as on the main stage.

Popular political discourse focuses on hand-wringing politicians and especially US and European leaders’ worries about and desires to contain China’s ‘rise’. But against this state-centric view is an equally troubling version of future-making shored up by state–market partnerships. This includes the increasing dependence of ‘the West’ on Chinese industries for consumption, investment, and so on, but also techno-economic enterprise between US or European and Chinese tech firms in Xinjiang and elsewhere. What Darren Byler (2021) calls terror capitalism offers an image of this futurity, in which the penal colony is used as a testbed to establish new surveillance capacities, forms of enclosure, and processes of unfree labour and extraction that can be sold and applied elsewhere. While this view is contradicted by the performative rhetoric of US leaders demanding export controls on artificial intelligence technology, computer chips, and 5G infrastructure, such uncertainty is perhaps the point. To understand this future-making requires us to look beyond familiar geopolitical spectacle.

4. Understanding the future in/of China must involve a renewed focus on the rural, among other techno–urban peripheries, even though futurity operates as a technology that at best ignores and at worst obscures rural conditions in China and globally.

An often assumed and under-questioned precondition of the future, in China and elsewhere, is the disappearance of the rural. Even the Maoist dictum of learning from the peasants was predicated on a future in which peasants would become (agricultural) industrialists, and rural villages would be turned into planned, orderly, electrified communities. The tension between the idea of the rural as an ideal counterpoint to present maladies and the imagination of the future as an urban imaginary continues to overlook and undervalue the realities of rural and peri-urban conditions in the contemporary moment. We need futures unhinged from the developmental paradigms that understand the rural as primitive, a raw materiality, or a space of tourist wonder. The aim is not nostalgia or a new Luddism, but to recognise so-called hinterlands as dynamic life-worlds whose needs and capacities already demand and make other futures.

5. The limits of political imagination are located precisely where the future collides with futurity.

Futurity is always located in the here and now; it is the imagination of the future from the perspective of the present. As such, we need futurities that are uncoupled from universalising paradigms of modernisation, technologisation, and urbanisation. To critique the limits of political imagination is to remind ourselves of the simultaneity of multiple presents and manifold political possibilities, the fact that rural and urban are inextricably enmeshed, visual and mediated constructions are creative and complicit, and memory processes are as much for the future as they are about the past. It is also about the supposed threat of global chaos that is repeatedly invoked by politicians and pundits in ‘the West’ should ‘our’ future become enfolded into China’s. The political project of the CCP has always been oriented towards the future; the project of China Studies, therefore, is to interrogate the political imagination of the future within the realities of the present (and the past). This means questioning not only claims made about China, but also our own assumptions about conditions in China and their effects on ‘the world’.

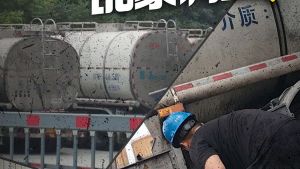

Cover Photo: ‘Chinese Dream Series I: Harmonious Society’, Alexander F. Yuan, 2016. Inkjet Print 90″ x 60″ and Online Interactive ChineseDreamArt.com. Used with permission of the artist.