Are You Okay?

I couldn’t be content with just reading books and visiting libraries. In a historical situation [the Algerian Revolution] in which in every moment, every political statement, every discussion, every petition, the whole reality was at stake, it was absolutely necessary to be at the heart of events and to form one’s own opinion, however dangerous it might have been—and dangerous as it was. To see, to record, to photograph: I have never accepted the separation between the theoretical construction of the object of research and the set of practical procedures without which there can be no real knowledge.

—Pierre Bourdieu[i]

Thursday, 18 April

‘They all got arrested.’

‘And the protest dispersed.’

Messages from S slowly came through thanks to the sporadic phone signal on the metro. All arrested while I’m still at Times Square.

‘Should I still come?’

‘I’m leaving.’

‘Ok, but a friend said more protesters were coming. Will be at Columbia in 10.’

‘Ok, lmk if I should come back.’

The cuticles on my fingers started to bug me. Why is the metro so slow? Why do people look at me? Is it because of my keffiyeh? Where are they all heading to? Why didn’t I get changed immediately?

It was Thursday, 18 April, the second day of Columbia University’s Gaza Solidarity Encampment. The day before, Columbia student activists descended on the west lawn before dawn and set up tents and Palestinian flags. It was planned for the day Columbia’s President Minouche Shafik would appear before the US Congress to discuss antisemitism on college campuses. A show of solidarity with Gazans, of whom at least 33,000 have been killed since October 2023,[ii] the encampment was intended to call attention to the role of the United States and Columbia University in supporting Israel’s Zionist regime.

The demand has been clear: disclose and divest. So far, 99.34 per cent of Columbia’s investment remains unknown, while the miniscule traceable fraction reveals its contribution to Israel and complicit companies, including Boeing, Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Caterpillar Inc.[iii] Boeing, for example, manufactures F-15 fighter jets and Apache AH-64 attack helicopters, which the Israeli Air Force has used extensively in its attacks on Gaza and Lebanon. Immediately after 7 October, Boeing expedited the delivery to Israel of 1,000 smart bombs and 1,800 JDAM kits (a tool that converts unguided bombs into precision-guided munitions). Hence, Columbia students have been urging their university to disclose its entire investment portfolio and divest from all companies profiting from the genocide of the Palestinian people.

Some might ask: Why call it a genocide? After Hamas’s surprise attack launched from the blockaded Gaza Strip into nearby Israeli towns on 7 October 2023, the Israeli Government declared a war of retaliation. What we have been witnessing is the displacement of Gaza’s entire population, the targeted destruction of life-sustaining infrastructure—hospitals, clinics, and schools in particular—the deliberate blocking and cutting of supply channels, and the selective bombing of southern Lebanon for deterrence. Destruction, devastation, bodies under the rubble. No escape. The strip is too narrow, the borders too rigid. Moreover, all atrocities have been legitimised by the language of dehumanisation, as in Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant’s appalling words: ‘We are fighting human animals.’[iv]

The brutality of this war on Gaza cannot be fully captured by our current political and legal vocabulary, yet we must call it a genocide. The current internationally recognised definition of genocide under the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention) specifies both the material and the physical elements of the crime: the ‘intent to destroy’ and acts to cause harm.[v] The Genocide Convention has been long criticised by many genocide scholars, however, as being biased and non-inclusive.[vi] The application of the genocide prism to Palestine in the past was rare outside activist and scholarly circles and, when applied, habitually evoked fanatical pushback.[vii] Even after the international uproar caused by the killing of World Central Kitchen aid workers on 1 April 2024, UK Foreign Secretary David Cameron in his article republished on the UK Government’s website stressed: ‘We must not forget how this conflict started—with the Jewish people suffering the worst and most murderous pogrom since the Holocaust.’[viii] The call for an immediate and permanent ceasefire, he stated, could not last unless ‘the cause of the conflict—the rule of Hamas over Gaza and the presence of those responsible for October 7’ were dealt with. What Cameron’s article points to is the recurrent insistence on the singularity of the Holocaust, which is furthered by governmental support and the institutional disciplining of modern genocidal studies.[ix]

To call what has been happening in Gaza genocide is therefore to recapture and reclaim the language to render these events legible to the current international legal and political system, despite its many flaws. It is to point to and insist again and again on the brutality and inhumanness of the war. It is to speak back to the weaponisation of antisemitism and to speak even louder in the stifling political atmosphere of censorship and intimidation that now greets any expression of support for Palestinians. Most fundamentally, we call it a genocide because it started not with Hamas’s attack on 7 October but with the perpetual genocidal violence that has been structurally produced by the establishment of Israel as a Zionist settler-colonial state.

I will not go into the violent history of the establishment of the Israeli Zionist regime,[x] but just imagine with me the life of Palestinians under Israeli rule in a time of non-war. Since the Second Intifada, Israeli military checkpoints have become part of the everyday carceral geography.[xi] The brutality of checkpoints does not work to stop Palestinian mobility in toto; they work to make the experience of everyday mobility arbitrary and uncertain. You line up in front of a checkpoint and start to worry: Do I look suspicious? Am I behaving properly? Will they search my body? What papers do they need? Do I have the right papers? Will they single me out? Will they beat me? Can I pass today? There are no definite answers.

The same logic of everyday randomness works in the most intimate space of home as well. You know Israeli soldiers may break in at night even if you have done nothing, but you don’t know when they will come, and you start to worry: Are they coming today? Can I sleep tonight? What will they do if they break in? You know Israeli soldiers can tear down your house at any moment, but you don’t know when they will come, and you start to worry: Are they coming today, or this week, or this month? Will I have time to evacuate? Is there anything valuable in the house? Can I rebuild my house? Do I have the money? Will they allow me to? Can I do it secretly? But how secretly?

The Israeli regime has subjected Palestinian lives to a constant state of anxiety and uncertainty, and it did not start with the Hamas attack of 7 October or the complete siege on Gaza since 2007. We must remember that the Gaza Strip was created by Zionist forces after the 1948 Nakba and was designed to accommodate 200,000 Palestinian refugees within its mere 365 square kilometres. I keep coming back to 1948. The date is significant because Palestinians live in the ongoing Nakba that is enabled by the binary discourse of civilians/non-civilians established with the proclamation of the Israeli Zionist state. This discourse justifies the state violence perpetuated by the Zionist regime in the name of the protection of civilians and creates the figure of the ‘non-civilian’. The life of the non-civilian—this potential criminal, this terrorist-to-be—is reduced to a matter of flesh and blood, for whom any expression, any look, any act can be read as suspicious and dangerous. And we call it a genocide because the Israeli regime denies the very humanness of Palestinians. The dehumanising power of the modern carceral nation-state has unleashed itself at a global level. The same logic of modern colonialism, supported by the same technology of surveillance developed out of racial capitalism, has been squeezing humanity out of our bodies from Kashmir to Xinjiang, from Tehran to New York on our own campuses.[xii]

A call for an emergency encampment picket was announced about noon on Thursday. It was said that New York Police were preparing to sweep the encampment while police buses had amassed on the street.

I saw the call and debated whether I should be there. I need to eat. I have a lot of work to do. I have a class in the evening. Columbia is far away—more than an hour’s metro ride. I don’t know many people at Columbia. What, after all, can I do? I was sitting at my desk, coming up with every excuse to not join. But, no. I need to go. I must go.

But I was too late. All the campers were arrested.

I walked up to the main gate of Columbia University. Police were lined up there. I glanced at them, and some looked back. I walked towards the small group of protestors at the location shared by a friend. I joined them and started chanting: ‘Free, Free Palestine!’

More police came. They came with bars to enclose us. Without much thinking, I rushed to stop them. No use. They were not afraid of touching my body or hurting me. Still chanting in the little enclosed space, I started to observe them. It was my first time being so close to the police. ‘NYPD, KKK, IOF, you are all the same,’ I shouted at their face. What are they thinking? Do they feel nervous or ashamed? Do they think it’s a mere child’s game? Don’t they have family and children? Why can’t they understand our fury and Palestinian pain?

A pat on the shoulder disrupted my thoughts.

‘Do you want some water?’

‘Oh yes, that’d be nice. Thank you.’

A girl in the group handed me a bottle of water.

D came closer, asking whether I was okay.

‘I’m all right. You okay?’

He nodded.

‘I need to go. But will come back later. Be safe.’

Eileen Chang says that we read romance novels before falling in love ourselves; our experience of life is always secondhand. True, I read about revolutions before experiencing and participating in one.

I was thinking about Cairo’s Tahrir Square the whole time. It was said that during the Egyptian Revolution, the centre of Tahrir became a tent city where people of every political stripe and social class gathered to exchange views about everything from religion to television and politics to football. It was said that even the most mundane acts, such as sweeping the streets and preparing food, became moments of inspiration. It was said that these daily practices turned Tahrir into a truly radical space. It was said that at Tahrir, fantasies were enacted and taboos were lifted.

When I first read about the Egyptian Revolution in my social anthropology class, I didn’t think too much about it. It was a week on the anthropology of revolution for which I needed to turn in an essay, analysing the cause of that rebellion. The transformation of Tahrir from a non-place into a liminal space suffused with egalitarianism and full of radical potentialities was not my major concern. At least, it did not touch me. All the rigorous analysis and vivid depictions failed to touch my heart.

But I experienced it then and there at Columbia, in New York. It was not secondhand. It was real. It was far more real than texts and images. I finally understood what all those scholars were talking about: revolution.

Monday, 22 April

Things moved very fast after that Thursday. As of 4 am, Monday, 22 April, the New York University (NYU) Palestine Solidarity Encampment was live. The same night, the police were called on to campus. More than 120 protestors, including faculty members who showed up to protect their students, were arrested. The plaza was cleared. A new wall was built. A university-wide email signed by university president Linda Mills and campus safety head Fountain Walker was sent, with misleading accounts of events at the encampment. Protesters were treated as mere bodies. Agitated bodies.

‘Are you cold?’ L asked.

‘Yeah, it’s freezing.’

We were standing outside the police station for jail support on Monday night. Too tired to talk, I started to check messages on my phone. People asking whether I was okay. Videos of police arresting protestors. Photos of people marching to jail to provide support. I turned off my screen. L hugged me. It was a cold night.

Friday, 26 April

On Friday, 26 April, the NYU Palestine Solidarity Encampment was alive again, this time in front of the Paulson Center, where communal programs had been held over the week. The police quickly showed up but left suddenly. Did they think there were too many of us this time?

More sleeping bags, yoga mats, blankets, water, and food were arriving. It is about protesting. It is also about claiming our own space and creating a new commune. At the encampment, there is a certain normalcy in the daily communal flow. We talk about our coursework and our finals. We discuss the best way to keep ourselves warm overnight. People come to ask whether we need more food, more blankets, more handwarmers, and whether we have rubbish to throw away or recycle. The day is divided by communal meetings, teach-ins, reading groups, film screenings, and eating, chatting, and sleep. You can say everything is mundane. You can say everything is revolutionary. Leaflets are distributed at the encampment: revolutionary poems printed in English, Arabic, and Hebrew; donation campaigns to help Palestinians evacuate Gaza with their families.

Some might scoff: You call it revolutionary? Is it not a game for privileged American white kids? Yes, to the first question and no to the second. As pointed out by Nasser Abourahme, we are trapped in the Eurocentric understanding of revolution as always about the physical seizure and overturning of the apparatus of central government. In relation to the Palestinian Revolution, he argues that what was revolutionary about the anticolonial experience was ‘its capacity to make territory’ that could ‘support new collective subjects and new forms of association that upended distinctions between governed and governing’.[xiii] In this sense, yes, the encampment is revolutionary. It is a mockery of the failed Israeli attempt to enclose Palestinians and of the modern carceral state’s failing attempt to contain and divide us into civilians and non-civilians. It is a refusal to follow the script of modernity that normalises monitoring and policing. It is a break from the compression of time and space coded by metro lines and campus security alerts. On the most fundamental level, it is revolutionary because it brings politics back to the centre of urban life.

And it is not a game played by privileged white American kids. The atrocities of the police and university administrators towards students—dragging them off to jail, beating them up, locating and harassing those yet to be arrested, suspending them, and evicting them from their accommodation—mean this is real life. We face the very real threat of verbal harassment, physical violence, and arrest. All is for Palestine. It is not a game.

The ‘we’ at the encampment of course includes, if you want, privileged white American kids. Yet, there are too many of us—the Black, the Brown, the trans, the queer, the disabled—who have been subjected to various forms of discrimination and violence. There are too many of us who can only rely on an F1 student visa and scholarships to stay in the United States. None of us can afford to be arrested. I am not suggesting that we do not live in a divided world or that commonality is synonymous with a homogeneous naivety. The point is, with an acknowledgement of the structural imbalance of power, we still find moments of peace and solidarity at the encampment. The experience of being together, of sharing personal stories and life rhythms, is empowering. We are making new words and placing them in the world, refusing the regime of ‘truth’ and the language of loss imposed by modern colonialism. We are learning how to be together with each other, how to treat one another as real human beings with our own struggles.

I left the encampment about midnight. My menstrual pain wouldn’t allow me to stay there the whole night.

‘I have to go.’

‘Okay. Take care. Let me know when you are home. And see you tomorrow?’

‘Yeah. See you tomorrow.’

Saturday, 27 April

I’m glad I’m not late this time. I’m relieved that I’m not ashamed about not camping overnight with friends. Of not being radical enough. Of not going to every protest. I have been an outlier in my field. The Chinese girl in Middle Eastern studies. What does she do? What’s her politics? I have turned away from working on Palestine even though the poems of Mahmoud Darwish were what first lured me in. I have felt ashamed of even mentioning why I got into the field: So, you know Darwish’s poems? I have asked myself repeatedly, who am I to write on Palestine? What do I know? Should I not make more space for people from the region? I have run away, because of my identity, my credentials—the lack of both.

The encampment changed everything. Strangers and friends all ask the same question: ‘Are you okay?’

No-one seemed to care about my identity. Or it stopped bothering me.

I no longer dwell on whether I have unique insights to offer. I act, and I own my credentials. I think, and I own my credentials. I write, with a broken heart for Palestine and a mended heart of love, and I own my credentials.

New York is a big city. Everyone has their own odds and ends to do. Everyone has their own way of fighting.

At the encampment, we demand an end to war profiteering and investment in genocide; shutting down NYU Tel Aviv, a campus built on stolen Palestinian land; removing Israel Occupation Force–trained racist police from our campus; and protecting free speech on campus and providing full amnesty to all students and faculty penalised for their pro-Palestinian activism.

We welcome you—as I was welcomed—whether you decide to join a teach-in about Palestine, to watch a film, to have dinner with us, to listen to music, to donate, or to camp overnight. An hour or two, a day, or several nights. What matters is that we are together. This is our space. We welcome you all. It is not too late.

A different version of this essay was originally published in Chinese in Tying Knots.

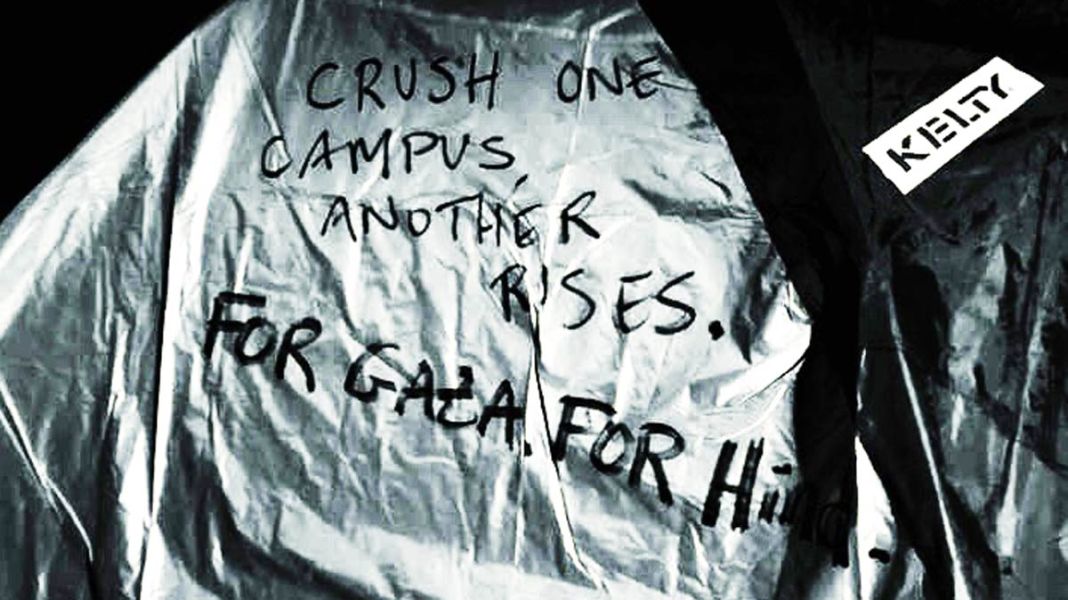

All photos were taken by the author at the pro-Palestine encampment at Columbia University.

Endnotes