Teaching China in Alabama Prisons in Six Objects

I celebrate teaching that enables transgressions—a movement against and beyond boundaries. It is that movement which makes education the practice of freedom.

—bell hooks (2014: 12)

All kinds of contraband items were smuggled into the Alabama prisons where I worked as an educator and administrative assistant from June 2022 to January 2024 through Auburn University’s Alabama Prison Arts + Education Program. Books, food, weapons, and drugs all made it inside. It seemed every week another correctional staff member or officer was being arrested for trafficking drugs (Darrington 2023; Harrell 2023; Rayburn 2024). With smuggled mobile phones, incarcerated individuals posted video updates on social media during an autumn 2022 state-wide prisoner work stoppage. Some incarcerated students with whom I worked told me this media, smuggled out of the prison, was why Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) Commissioner John Hamm announced that contraband mobile phones were one of the top two problems Alabama prisons faced (Cason 2023), rather than the many other problems identified by everyone else—from the US Department of Justice (2019) to students with whom I worked (Dowdell 2023; Johnson 2024)—which make Alabama prisons some of the worst in the country.

During my year and a half with the Auburn University program, I started to think of education as a kind of smuggling, too. Though I was ostensibly there as an administrative assistant and to teach a general interest course about China, the educational exchanges that occurred went far beyond this scope. My experiences convinced me that prison education can act as an institutionally legitimate package through which educators can bring knowledge, intellectual resources, perspectives, and opportunities sorely needed in prisons. For self-reflective educators, prison education offers the chance to co-pilot radical, life-affirming learning journeys with some of the most motivated but disinherited people in the United States. Now is the time for educators to claim these people as students and reorient their vocation to align with the urgent goal of ending mass incarceration—the most brutal system our society currently wields to manage inequality within its borders.

While every educator regardless of field of study can contribute to transformative education in prisons, here I use my experiences leading three semesters of a general interest course on China to think through potential contributions China Studies educators can make.

This essay draws on anecdotes, students’ work, qualitative assessments of the class, and my own weekly reports. I share several scenes from my time teaching in four Alabama State prisons. Each scene could be unpacked productively but endlessly to demonstrate how China Studies can be relevant. Instead, I allow classroom experiences to speak for themselves in ways I hope provoke curiosity and conversation. This essay seeks to encourage China Studies educators to realise that their knowledge, if packaged correctly, could carry value through the prison gates.

A Scroll, Part One

On the last day of what came to be called ‘the China class’ at Tutwiler Prison for Women, I arranged for a guest to teach Qigong. Inside the cafeteria, the teacher introduced the subject and showed students a scroll illustrating the poses comprising the ‘eight brocades’ (八段锦) series. I had been given the scroll while leading a study trip to Wudang Mountain and felt showing it would anchor our Qigong practice to its origin.

Correctional officers allowed us to practise the eight brocades outside in the prison yard. After a demonstration by the teacher, we walked through the movements together. Laughter and questions lit up the yard. Incarcerated women not in the class looked on, seemingly bewildered.

Once we had the moves down, we practised the series again in silence. The sound of a helicopter far in the distance started growing louder until, suddenly, it appeared over the pine trees and paused just overhead. It tipped slightly, and it was clear that whoever was inside was watching us.

As it hovered there, I fidgeted, examining the faces of the correctional officers for signs that we should stop. I looked at the students, some of whom waved to the helicopter. Despite this intense distraction, the teacher continued the moves calmly, as though the helicopter were not there. Eventually it leaned away and departed.

Though we never addressed the moment, it stuck with me. With her fluid movements and stoic composure, the teacher taught something essential about Qigong. She seemed to be saying: Anything superfluous to what we’re doing right now may as well not exist. It was a message I think these students understood better than I could. That class was one of their favourites.

A Broken Tooth

In all three sessions of ‘the China class’, I taught language skills. I hoped this would render foreign syllables more accessible and help students remember the names of places and people we would be discussing. I also hoped this would encourage students who might have had negative experiences with schooling to realise that learning something that sounded as difficult as Chinese was within their abilities.

One day during language practice, Joe (all names in this essay are pseudonyms) said he simply could not pronounce Chinese. ‘Of course, you can!’ I said and launched into encouragements and critiques of typical language classes. ‘So, you see, you can learn it!’

Joe said: ‘No, I mean I really can’t pronounce these words.’ He opened his mouth and pointed to a broken front tooth. Joe had been trying to see a dentist for a while, he said, but Alabama prison doctors consider problems with the front teeth ‘aesthetic’ and they are thus excluded from health care. Other students agreed: you needed four missing molars to qualify for dental work.

Beside the prison’s gross indifference towards human wellbeing, another problem for language teaching was a lack of contact hours. Class time was not nearly enough to progress in language acquisition. It was a student I tutored at another prison who solved this problem. He pointed out that the Securus Technologies tablets available in Alabama prisons could access a Chinese-language podcast. He encouraged me to contact the company.

Coffee Break Languages was happy to send me a free PDF textbook to use with these students. Their email read: ‘We appreciate your patience and the commitment to your initiative, a very worthy cause!’ So, there it was: manufactured scarcity could be analysed and overcome through dialogue, creativity, and relationship-building. With this, I was able to plan lessons around audio and text resources that students could access outside class. They progressed rapidly.

‘The most researched and utilized metrics to evaluate the success of a higher education in prison program have been 1) recidivism rates and 2) improving employment outcomes,’ writes a former student, C.D. (2023: 5), in his undergraduate thesis. But the pleasure and validation students received from learning Mandarin demonstrate why prison education must go beyond these seemingly pragmatic goals. When asked whether ‘the China class’ would help him in the future, one student wrote: ‘Yes. All education is important’ (Feedback 1).

A Cotton Boll

The drives from Auburn University to the prisons where I taught led through depressed rural towns and surrounding fields. On long commutes, I watched the cotton ripen and, for several weeks in the autumn, wisps of cotton dropped from trucks rolled along the road in the late afternoon sun. One day I stopped and picked one up.

I had been tutoring a Kazakh friend from China called Mubarak. Without knowing exactly why, that day I presented her with the piece of cotton. She said it was beautiful. Then she told me a story about accompanying her father, who was a public servant, to pick cotton as part of a government campaign. Once, to motivate his young daughter, Mubarak’s father promised her a reward if she picked a certain amount by the end of the day. To hasten a conclusion to the work, Mubarak weighed down her bag with rocks. Her father discovered the ploy, but she still received her prize. She laughed at this memory.

Immediately, I recalled a story from the life of Fannie Lou Hamer. In a 1965 interview, Hamer recounts her own introduction to cotton:

I was six years old and I was playing beside the road and this plantation owner drove up to me and stopped and asked me ‘could I pick cotton.’ I told him I didn’t know and he said, ‘Yes, you can. I will give you things that you want from the commissary store’ … So I picked the 30 pounds of cotton that week, but I found out what actually happened was he was trapping me into beginning the work I was to keep doing and I never did get out of his debt again. (O’Dell 1965)

Like the scroll, the cotton boll fastened two distant realities together: one in the US South and one in Xinjiang, China. Mubarak was applying for political asylum in the United States because of her experiences in Xinjiang—experiences echoed in Hamer’s, Frantz Fanon’s and any number of other accounts of colonised people, but also in those of my students and their ancestors. This is why I hoped to bring Mubarak into the prison as a guest lecturer. Ultimately, ADOC never cleared her, but I shared some of her experiences with the students and some of the students’ experiences with her because I believed such traffic in testimony could be a powerful educational intervention. Shared sentiment can pry open space where empathy and understanding can amass and where solidarity can find fertile ground in which to root.

Socks

‘If we are to have peace on earth … our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation; and this means we must develop a world perspective,’ Martin Luther King, jr, wrote in 1967. In ‘the China class’, we tried to develop this world perspective in a few ways.

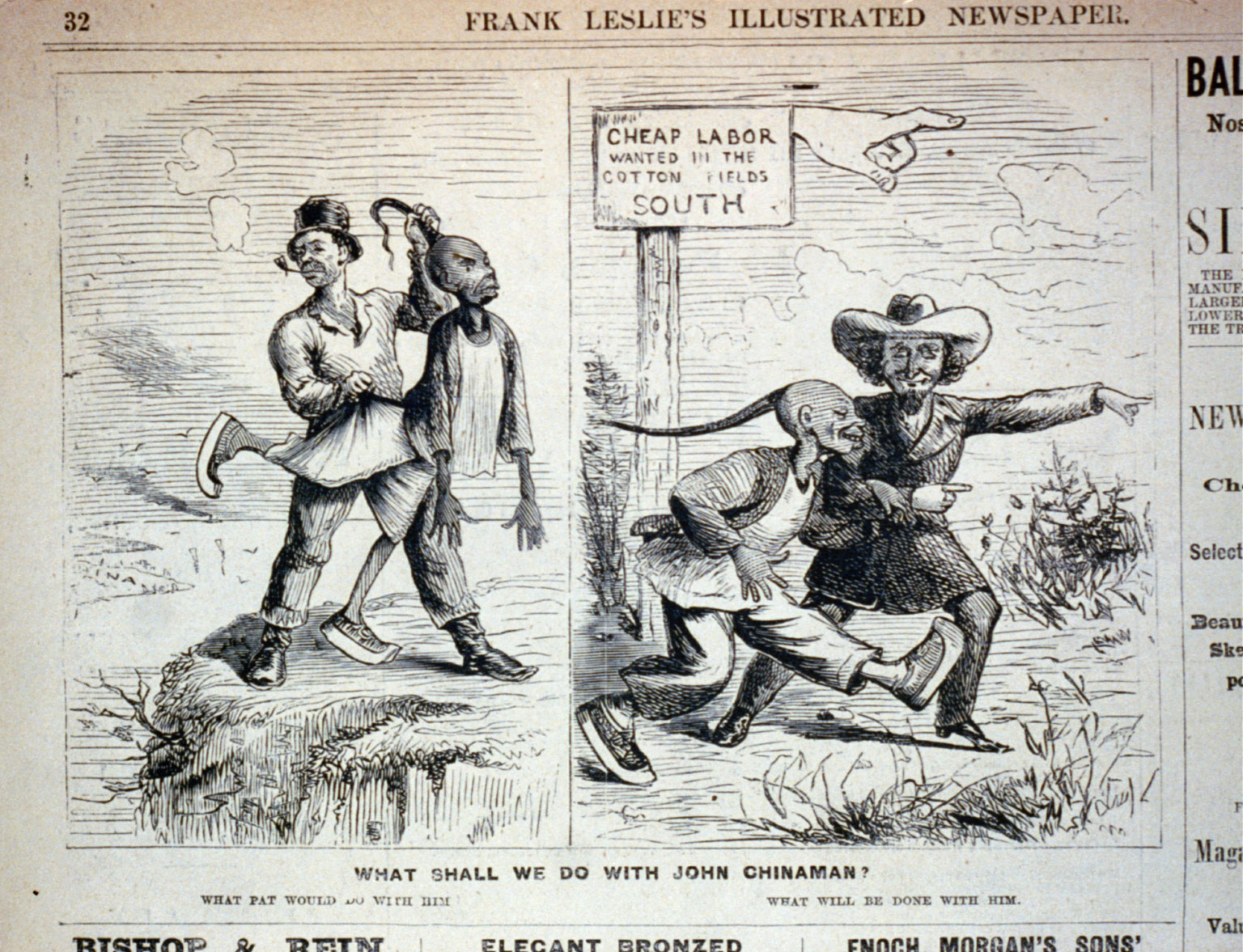

We addressed the origins of the anti-Asian racism and Sinophobia prevalent during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Mae Ngai’s (2021) work helped us review the anti-Asian laws, vigilante violence, and racist stereotypes during the California Goldrush. Responses to bubonic plague outbreaks in Honolulu and San Francisco demonstrated the racist association between Chinese and disease (Risse 2012; PBS 2022; Heinrich 2008). After the US Civil War, the aborted scheme to transport Chinese labourers to the cotton fields of the South to replace enslaved labour showed capital’s tendency to use racism as a wedge between similarly situated people; the same was true in how white immigrant labour organisers used Chinese as bogeymen, ultimately preventing cross-racial organising and contributing motivation for emerging racist immigration regimes in the United States and Australia. We traced how those same stereotypes operated in the present, as with Donald Trump’s ‘China virus’ slogan and the nearby 2021 Atlanta spa shootings.

Studying that history helped students disaggregate China, breaking their habit of seeing China and the Chinese as commutable, and engendering a new habit of seeing poor, labouring, incarcerated, or racially othered Chinese as similarly situated peers. Armed with that information, we could see that political stances towards China other than Sinophobia were possible.

Another component of this ‘world perspective’ was the work we did on globalisation and responses to it—globalist, internationalist, nationalist. We needed to analyse the material ways—not just the sentimental ways—students’ lives intersected with counterparts in China. I wanted to upset the assumption that life here occurs independently of life there, and that assumption’s ethical corollary: that domestic ‘countrymen’ necessarily share our conditions and deserve our loyalty above foreigners. In place of Sinophobia, I wanted to propose a political cosmopolitanism informed by analyses of globalisation, class, race, and gender.

But first, demonstrating interconnectedness. If the students had taken off their shoes and had a look, they might have read the following label: ‘Shoe Corp Style No. N194, Size: 13. Made in China. Order No. T946.’ From the shoes and socks on their feet to the Securus Technologies tablets in their hands and the MICOOYO-brand cotton surgical masks used during Covid-19 and tuberculosis outbreaks to the Bob Barker ‘orange anti-shank razors’—most students’ stuff had been manufactured in China. And these commodities materially connected the incarcerated students to the processes that produced them.

We took socks as an example. ‘At the [hosiery] industry’s peak in the 1990s, more than 120 mills employed roughly 7,500 workers’ in Fort Payne, Alabama; then, ‘[s]eemingly overnight, the mills closed, and the new Fort Payne became a town in China called Datang’ (Kurutz 2016). Students who did not come from Fort Payne came from places like it and could understand it. As for Datang, I decided to show them this new ‘sock capital of the world’ by visiting it myself. I hoped that showing the two places side by side would illuminate how the ‘China economic miracle’ and US deindustrialisation, which ‘eliminated 9 out of 10 textile and apparel jobs in the south’, were not independent developments (Bolden 2014: 16).

In Datang, the streets teamed with three-wheeled carts carrying huge spools of thread around the town. Semitrailer trucks parked in the road, loading and unloading. In front of restaurants and convenience stores, owners sat on small plastic stools finishing by hand pair after pair of socks to make some side money. I took pictures of factories, spoke to sock manufacturers and thread merchants, and toured a massive wholesale market.

I also asked about sourcing, and here is where that cotton boll comes back into the story. I heard that almost all of Datang’s cotton came from Xinjiang. Since the 1990s, Xinjiang has produced an increasing percentage of China’s cotton. Official data calculates 5.2 million tons of cotton, over 90 per cent of China’s total for 2023, emerged from Xinjiang (Yin 2024). If that cotton was harvested and processed using coerced labour, as many studies claim, that would mean that any product my students wore made from that Chinese cotton likely involved coercion (Murphy 2021). That material connection between the socks on students’ feet and the processes that produced them suddenly took on ethical and pollical dimensions—dimensions that incarcerated students understand in a different way than a typical college student because of their own experiences with the coerced labour regimes prisons rely on to exist.

After the US Civil War, the profit motive, which had always been present in Alabama’s penitentiaries (Ward and Rogers 2003: 82), reached a brutal apogee in the system of arbitrary arrests, ubiquitous corruption of judges and sheriffs, and selling of imprisoned people to private companies—the convict lease system (Blackmon 2009). Although convict leasing—and the chain gangs labouring on public works—faded by the middle of the twentieth century, coerced labour continued: in prison plantations, factories, offsite work release centres, and the many tasks within prisons. Much of this labour is unpaid and all of it is subject to the potential coercion omnipresent wherever strong asymmetric power relations exist. Although Alabama voted in 2022 to remove the exception clause from the State Constitution’s version of the federal Thirteenth Amendment—the notorious clause that allows slavery as a punishment for a crime—because the federal amendment still contains this clause, the ramifications of this change must be tested through litigation. Another former student writes in his undergraduate thesis: ‘A yet-to-be-answered question the [2022 Alabama] amendment raises is whether it implies Alabama state prisoners are now eligible to receive living wages for the labour they currently perform for little or no compensation’ (X 2023: 2). Lawsuits alleging slavery (McDowell and Mason 2024; Rocha 2024; US District Court 2023), illegal living conditions (US Department of Justice 2019), healthcare fraud (Fenne 2023), and even organ harvesting (Hrynkiw 2024) continuously emerge from Alabama prisons to push back against systemic brutality.

But these places are connected to northwestern China not only through supply chains and parallels in labour conditions and legal regimes but also through historical interaction. Cotton production first revved up in Central Asia as a response to the ‘cotton famine’ created by the US Civil War. ‘By the late 1850s, the United States accounted for … as much as 92 percent of the 102 million pounds [of cotton] manufactured in Russia’ (Beckert 2004: 1408–9). When that supply was blocked by the Union, the Russian Empire redoubled its efforts to colonise Central Asia, turning it into a cotton-producing area where the empire would find ‘our Negroes’, according to an empire spokesperson (quoted in Beckert 2004: 1430)—much in the same way postbellum planters hoped Chinese could replace formerly enslaved African Americans.

This is what I call teaching about China and teaching through China. The deindustrialisation that plunged many of my students and their families into poverty and led in part to the opioid epidemic plaguing Alabama (and most of all its prisons) had its counterpart in the rapid industrialisation of China’s eastern seaboard, which lured millions of farmers into becoming precarious urban workers in export manufacturing, which was the same development that pushed Xinjiang away from subsistence farming and towards outsider-controlled industrialised farming of cash crops. The criminalisation of the entire population of southern Xinjiang and their transformation into devalued racialised workers means the logic of racial capitalism that has always haunted industrialised cotton production continues (Wong 2022).

By ‘de-invisibilising’ the supply chain, we began to see that supply chains were dispersed precisely to enable exploitation. If we then consume the products that are affordable because they rely on exploitation, do we incur an ethical debt? Whether students conceived of themselves as victims or perpetrators, I hoped they would think about how the socks on their feet could pull them into a relationship with distant people. But where to go from there?

A Little Red Book

We explored how empathy and the shared material entanglements produced by globalisation could motivate political solidarity through what Dr Keisha Brown calls Sino-Black relations. We began with a video of Huey Newton holding up a copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tsetung as he spoke to a crowd and asked how Huey came to have that book and why he found power in it.

We used scholarship by Brown, Robin D.G. Kelley (2015), and Robeson Taj Frazier to lean into these connections between Black America and China. We studied post–World War II decolonisation, the Black Belt Thesis, and Mao’s letters to Black Americans in the 1960s. We discussed socialism and Leninism in the context of the Black Panthers’ Ten-Point Program and asked why Maoism appealed to revolutionaries globally.

We discussed the influence of kung-fu on Black cultural production. We watched Kareem Abdul-Jabbar kicking Bruce Lee’s arse in Game of Death (1978) and talked about the Wu-Tang Clan’s origin story and the lyrics of Oakland’s The Coup. A favourite during all three semesters was the class on music. We learned about American jazz’s influence on shidaiqu (时代曲, what we think of as Shanghai jazz age music), read Roar China! by Langston Hughes, and watched Black cultural and political icon Paul Robeson perform ‘March of the Volunteers’ (义勇军进行曲).

We listened to ‘Made in China’ by the Chinese rap group the Higher Brothers and discussed nationalism and whether artists who adopt Black musical forms have a responsibility to support Black political movements. We put Chinese hip-hop from the 88rising record label into conversation with Mao’s 1942 Talks on Art and Literature at the Yan’an Forum and asked whether hip-hop requires a political message to be hip-hop.

I hoped all this could give students a way to place the politics of racism in the United States in a global context and help them to see their ‘fate linked with that of colonised’ people elsewhere, as bell hooks (2014: 53) writes of Paulo Freire’s influence on her. This linked fate, so like King’s ‘world perspective’, certainly animated the figures we studied. In a 1939 interview, Robeson said:

I’ve learned that my people are not the only ones oppressed. That it is the same for Jews or Chinese as for Negroes … I found that where forces have been the same, whether people weave, build, pick cotton, or dig in the mines, they understand each other in the common language of work, suffering and protest. (Robeson 1978: 131–32)

Hughes (1937) expresses a similar perspective:

Break the chains of the East,

Child slaves in the factories!

Smash the iron gates of the Concessions!

Smash the pious doors of the missionary houses!

Smash the revolving doors of the Jim Crow YMCAs.

Crush the enemies of land and bread and freedom!

That same internationalism animating Hughes and Robeson continued through Huey Newton, the Third World Liberation Front at San Francisco State College, and is at work in former frontman of The Coup, Boots Riley. Because we studied all of this within the context of statewide work stoppages organised in Alabama prisons in the autumn of 2022 (Sainato 2022), our studies and our lives came into conversation, and we came to see how people in two very distant places claimed one another as compatriots and intervened positively in one another’s lives. Again, ‘[o]ur loyalties must transcend’ (King 1967).

A Letter

I had my own agenda, limitations, and blindspots as a teacher, so I wanted students to hear from as many other people as possible. Struggling to gain approval for guest speakers, I instead asked friends in China to record videos. In video letters, they addressed the class and shared their daily lives: purchasing moon cakes, using public transportation, cooking, travelling, and touring a museum. I asked friends to think about what kinds of things they would like to share about China if they had the chance to communicate directly with incarcerated students.

The next semester, students drafted two boilerplate letters, one to Chinese locals and another to China scholars. These letters requested video contributions so future sessions of ‘the China class’ could access even more high-quality materials.

Their letter read:

As incarcerated Individuals, resources for learning are not widely available to us. In the few instances where genuine education is available, topics are limited in breadth and scope. We are incredibly grateful for the opportunity to learn and take part in the larger movement to improve education everywhere.

It is obvious that many of society’s ills could be remedied with better and more widespread information, especially in areas of study that connect deeply with contemporary issues. The aim of this class in particular is to help open more minds to China’s strengths and weaknesses, and the things we can incorporate into our own lives for the better. This is where we could use your help.

We would be extremely grateful if you could compose a short, 2–8-minute video that we could use to introduce people to your area of study and perhaps interest them to look more deeply. We leave it to you to decide what exactly should be included but hope for the highlights you consider pivotal in your field.

Thank you for your time, attention, and involvement.

Other Chinas Class of________

___________________ Prison

_____________, Alabama, USA

I continued to gather videos from friends in China and, with the students’ letter, I reached out to China scholars. The response was overwhelming. Scholars gave suggestions and encouragement, shared experiences and pointed to good teaching materials, and many ended up recording videos.

The political kung-fu of this project is that I considered the people who contributed videos as a secondary, covert audience. Friends in China were pushed to think about prisons and education at home and abroad and had to think through what they wanted this demographic to know about China. Conversations on social media began. Professors and practitioners of traditional Chinese arts were introduced to prisons and prison education—some for the first time. Conversations on listservs began.

A Scroll, Part Two

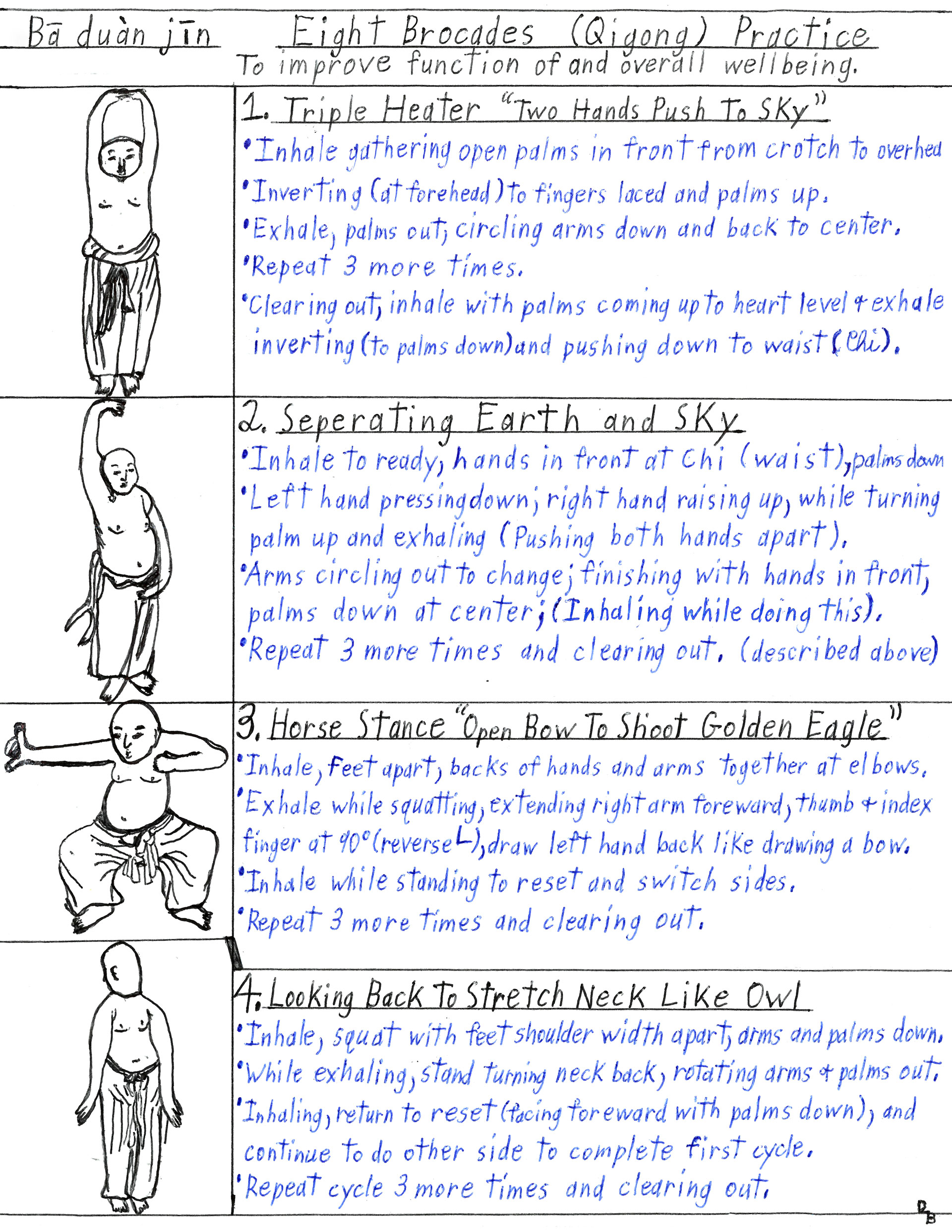

Encouraged by the students’ positive reaction to Qigong, during the final semester of ‘the China class’, we did much more. We began each session by following Mimi Kuo-Deemer’s video of the eight brocades. The practice built a predictable structure, set a calm energy, and sufficient repetition allowed students to memorise the moves so they could take it forward.

As with all activities, students could participate in any non-disruptive way they wanted or choose to sit it out. Some students jumped right in while others hesitated. Jokes abounded. One of the moves, ‘Sway the Head and Shake the Tail to Eliminate Heart Fire’ (摇头摆尾去心火), became known as ‘The Beyoncé’.

Near the end of the semester, students led the series without the video. It was bumpy, but they helped one another by tagging in when whoever was leading became stuck. Even students who seemed checked out could surprise; one who never participated used illustrations taken from Pan Fei’s (潘霨) 1858 Hygiene Essentials (卫生要术) to hand-illustrate the movements and placed this alongside detailed instructions he had transcribed from the video. I made copies for the class.

Later, I found an email address for Mimi Kuo-Deemer, whose video we had used, and showed her the student’s illustration. She praised the resource and offered him suggestions to improve it further. She also agreed to record a video for future classes. There again, walls had been bypassed and manufactured scarcity overcome through dialogue, creativity, and relationship-building—that and a generosity of heart.

Smuggling as a Metaphor

I hope these scenes illustrate a few points. China Studies educators clearly can teach in ways meaningful and relevant to students incarcerated in US prisons. They can do this by teaching about China and through China.

About the class, one student said their understanding of history had ‘drastically changed. I thought I knew, but I had no idea the part that China & its people have played throughout history’ (Feedback 2). Another student wrote: ‘To understand a different culture and be able to respect that culture will open doors that are shut due to ignorance, racism, and closemindedness’ (Feedback 3). And another: ‘We would love to have a second China class. We only scratched the surface of such a diverse culture, and so much can be learned’ (Feedback 4).

China educators may also find prisons fertile ground for topics other than what they may typically choose. Working through anti-Asian bias and Sinophobia seems a worthwhile goal. Fraught topics such as race, socialism, and colonialism can also be taught productively in the Chinese context first, yielding insights that can then be transposed to the higher-stakes context of our own society. Postwar decolonisation is a undertaught yet crucial period that intertwines Chinese history with that of the United States. Globalisation in the United States cannot be understood without China.

Even students who had a more complex relationship with the class got something out of it: the student who stole pens to sell for tattoo ink, the student who goaded me by repeating anti-Chinese stereotypes, students who came to class high, students who slept through parts of the class, the student who one day screamed at demons the rest of us could not see. There is such an astounding need for compassionate, empowering teaching, and I have no doubt this can be smuggled in under the guise of China Studies just as well as any other subject.

Just as much may be smuggled out. The realities of teaching incarcerated students can push China scholars to radically reassess their own work. The need to connect with a different demographic inevitably pushes educators to familiarise themselves with new areas. Within their expertise, interacting with incarcerated students may push them to rethink less commonly taught topics or push scholars to expand the scope of future research.

Encounters in places of such great need pry open cracks in our lives. They leave us changed and desperate to change what is not right. Through substantive interactions with people of vastly different experiences and circumstances, students and teachers grow in knowledge and compassion but also in their political vision. For reflective educators, opportunities for experiments in what bell hooks calls education for critical consciousness or liberatory education abound. With the right advice, sufficient caution, and a willingness to learn prison codes, educators can be part of an education but also a movement. Our teaching can affirm the right of every person to grow irrespective of their past, offer therapeutic value in non-invasive ways, and develop skills crucial for engaging in civic life.

A vibrant prison education ecology once existed until ‘tough-on-crime’ politicians decimated it by withdrawing from incarcerated people eligibility for Pell Grants (government education subsidies). By the early 1990s, 782 programs for higher education in prison existed but, by 1997, only about eight remained (C.D. 2023: 21). Recent changes to restore Pell Grant eligibility to incarcerated students mean we are on the verge of a renaissance in prison education. There has never been a better time to get involved.

As for my time teaching China in Alabama prisons, I am forever changed. I will always remember the sight of 12 women following a teacher through the flowing movements of the eight brocades while a helicopter watched from the sky above. This moment was one that easily could have never happened. Yet, we created it. Was it a showdown? If so, between what? Was it something else? Regardless, from that moment, I believe we all received some sense of our power to move in a place so defined by its power to arrest. At that moment, the students and the teachers were free.

Acknowledgements

Many of the lessons were developed in discussion with colleagues, students, and Chinese locals. Conversations with Jason Wren and Robert Sember of The New School were especially important. Likewise, conversations that spun off an initial email to the Critical China Scholars also proved to be a great help. Many people in the United States, China, and elsewhere lent time and energy to the projects described here. Thank you.

Cover Photo: Families gather between the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church and the Alabama capitol building in a vigil for their loved ones, among the other 266 people who died in ADOC custody of the Alabama Department of Corrections in 2022 (the number grew to 325 in 2023). Seated is Lonnie Holley, world-renowned multimedia artist, himself incarcerated as a child at Mount Meigs and one of the figures the students at the centre of this essay studied in art history class. 10 March 2023, Montgomery, Alabama.

References