The Beastly Politics of China’s Margins

Under Xi Jinping, China’s policies towards minorities have taken an aggressively assimilationist turn. But even before the Xi era, for many of the ethnic minorities of China’s borderlands, the early twenty-first century was a time of social upheaval that generated profound anxieties about culture loss. The ‘Open Up the West’ (西部大开发) development campaign, launched in 1999, was accompanied by environmental policies that upended traditional livelihoods, such as mobile pastoralism, and brought rapid urbanisation and intensified resource extraction to minority areas.

As intellectuals in China—both minority and some Han—have grappled with the rapid social, cultural, and ecological transformations of the country’s peripheries, they have often turned to animals as a metaphorical resource for discussing the plight of ethnic minorities within the country. At the same time, for rural pastoralist minorities, the upheaval of the early twenty-first century has often entailed the loss of, or estrangement from, their animals (White 2021). In this essay, I analyse the role of animals in the politics of China’s margins and suggest that this beastly politics illuminates fraught issues of minority agency, autonomy, and assimilation in contemporary China. I show how the association between minorities and animals has been variously deployed and contested by different actors and draw on my ethnography of western Inner Mongolia to explore the ambiguities and tensions of a politics of minority cultural survival framed in animal terms.

Beastly politics has a long history in China. In keeping with many other imperial formations around the world, the peoples of China’s peripheries were for centuries imagined as ‘barbarians’, who were closer to animals than humans and in need of civilising by the political and cultural centre. Such bestial understandings of these peoples were reflected, for example, in Tang descriptions of their physiognomy (Abramson 2003: 130). For centuries, the association of these non-Han peoples with animals was even inscribed into the Chinese language itself. The characters representing these peoples often included a radical indicating an animal—notably, insect (虫) or dog (犬)—thus in effect classifying that particular people as a subset of that type of nonhuman being (Fiskesjö 2011).

In the twentieth century, the animal radicals in these characters, and the imperial chauvinism they implied, sat ill with formal declarations of equality among nationalities (民族) on the part of the modernising Chinese state, and their excision was finally announced in 1940 (Fiskesjö 2011). The anthropologist Magnus Fiskesjö (2011), however, argues that the association of non-Han peoples and animals has continued into the People’s Republic of China, where minority nationalities (少数民族) are still regarded as ‘backward’ and ‘closer to nature’. According to Fiskesjö (2011: 73), the survival of this association is down to the fact that it allows the ruling elite to represent themselves to the majority of their subjects as ‘the universal centre of an eternal order’.

The Representational Politics of Animals in the Early Twenty-First Century

In the realm of cultural production, the association of minorities and animals formed a continuity between the Maoist and reform eras, despite their very different policies towards minorities. For example, while representations of animals were largely absent from animations produced during the Cultural Revolution, animated films that featured minority nationalities were an exception (Du 2016). In the reform era, as ethnic otherness became increasingly commodified, it was often linked to youth, femininity, and animality: cards and bookmarks produced by the Nationalities Publishing House in Beijing, for instance, featured minority girls who ‘occasionally appeared to be in direct communication with the animals who inhabited [their] environs’ (Schein 1997). Birds, lambs, and butterflies predominated here.

In the early 2000s, however, the intersection of ethnicity, gender, and animality in Chinese cultural production shifted significantly. The 2004 novel by Jiang Rong (the pen-name of Lü Jiamin), Wolf Totem (狼图腾), quickly became a Chinese and then global publishing phenomenon, eventually being made into a film. The novel draws on the experiences of the Han Chinese writer himself, who was sent down to Inner Mongolia during the Cultural Revolution. Contrasting the sheep-like Han and the wolf-like Mongols, the novel criticises the destruction of the Inner Mongolian environment that has accompanied the expansion of Han Chinese farming and celebrates the ecological role of wolves and Mongols in maintaining the grasslands. The extinction of the wolf functions as an allegory for the decline of Mongol nomadic power. Rather than seeing the Mongols as a threat to China, Jiang Rong suggested that they have historically constituted an important source of vitality and virility for the Chinese nation, and that China, faced with enemies abroad, now needed a reinfusion of this kind of wild animality from the peripheries.

In the wake of Wolf Totem several novels were published that dramatised China’s ethnic politics using an animal cast, including Yang Zhijun’s 2005 Tibetan Mastiff (藏獒). In this book, however, the wolfishness of the Mongols was contrasted negatively with the loyalty of the Tibetans-as-mastiffs. The tractability of domestic animals thus provided a useful way of portraying an ideal of faithful, obedient minorities—a trope also evident in recent media reports and films portraying the work of border patrols that still make use of animals for transportation (White 2023).

There have been numerous critiques of Wolf Totem, not least on the part of China’s Mongols themselves. As Inner Mongolian anthropologist Nasan Bayar (2014) points out, it had the effect of reducing Mongols to ‘Viagra for the Chinese’. Other Mongol scholars have criticised fundamental inaccuracies in the novel, including the very idea of the Mongols having a ‘wolf totem’. According to the writer Guo Xuebo, ‘Wolves were considered the natural enemies of Mongolians.’ He goes on to lambast Jiang Rong’s novel for its ‘antihuman, fascist thought’ (cited in Visser 2019: 337). Here, then, we can see how some minority intellectuals have contested certain dominant representations that identify minorities with animals. Indeed, in criticising the novel as ‘antihuman’ (反人), Guo seems to turn Jiang Rong’s celebration of animality back at him.

However, in the early twenty-first century, minority intellectuals have in fact often reappropriated the association of minorities and animals, rather than contesting it. Despite declaring wolves ‘natural enemies’, Guo Xuebo (2001) has himself written novels that lament the extinction of these animals and associate it with the destruction of the environment. Through the care and respect for wild animals shown by his Mongol protagonists, Guo suggests that Mongolian culture is characterised by sympathy for animals (Baranovitch 2021). Tibetan writers and filmmakers have similarly foregrounded close relations between Tibetans and animals in their works (Vitali 2015; Baranovitch 2023).

This use of animals could be understood as a form of ethnic politics at the level of representation (Lo 2019). In an age in which the Chinese state trumpets the importance of environmental protection, these writers and filmmakers contrast minority compassion for animals with an environmental destructiveness that is associated with Han Chinese, thereby contesting longstanding representations of minority deficiency according to developmentalist logic. At the same time, stories of animals also work allegorically, with the extinction of certain species such as wolves, for example, gesturing at anxieties over the fate of minority peoples themselves in the face of assimilationist pressures in the twenty-first century. In the context of the heightened political sensitivities that surround discussion of minorities in China, this allegorical mode enables the oblique criticism of developmentalist policies and the ecological and cultural destruction they have wrought (Baranovitch 2021).

Livestock Conservation in an Age of State Environmentalism

Beastly politics in twenty-first-century China has not been confined to the artistic realm. Minority actors have also pursued projects of cultural survival by invoking the endangerment of certain animals and mobilising around their conservation. In Inner Mongolia, the defence of Mongolian pastoralist traditions of land use came to be framed in terms of the protection of certain charismatic species of livestock. In addition to emphasising the benign ecological effects and potential economic value of these animals, this politics drew on, but also transformed, the symbolic associations of minorities and animals that circulated in Chinese culture in the early twenty-first century. This beastly politics illuminates some of the tensions between otherness and assimilation characteristic of nation-building in contemporary China.

If the Open Up the West strategy framed China’s western regions as areas in need of rapid development, it also brought in its wake environmental policies that sought to address the perceived degradation of western landscapes. On China’s vast grasslands, pastoralists (often minorities) and their animals were blamed for causing desertification, and a series of policies were implemented. These included the resettlement of herders away from the grasslands—known as ‘ecological migration’ (生态移民)—but also grazing bans and strict limits on the number of animals herders could keep. Some scholars have argued that these measures are as much about securing state control over ethnic minority borderlands as they are about environmental protection (Li and Shapiro 2020).

But these policies have not gone uncontested. In late-twentieth-century China, endangered species protection had become one of the earliest permitted domains of civil society mobilisation, and these efforts were often focused on the charismatic megafauna of China’s western regions, such as the Tibetan antelope (Yeh 2014). In certain parts of Inner Mongolia, local Mongol elites appropriated these discourses of species conservation to defend pastoralist land use, by focusing on endangered breeds of livestock associated with extensive pastoralism on unenclosed grasslands. In 2009 in the east of the region, local Mongols sought to protect the Mongolian horse, and the culture associated with it, by establishing a Horse Culture Society. Horse numbers had fallen precipitously, partly because of their obsolescence as a means of transport. This society formed alliances with Beijing-based environmental nongovernmental organisations and sought to encourage the local government to change its grassland management policies (Zhou 2010).

Given the centrality of the horse in Mongolian culture, the endangerment of this animal evocatively symbolised the perceived plight of the Mongol nationality at a time of rapid urbanisation, resource extraction, and state environmentalism. A few years earlier, Season of the Horse (季风中的马), a 2005 film by the Mongol filmmaker Ning Cai, had used its animal protagonist, an old and ponderous horse, to suggest the predicament of the Mongols in Inner Mongolia. Attempts to save the Mongolian horse were also a form of politics freighted with symbolism, in which the horse could stand as a synecdoche for Mongolian culture more broadly. What is more, in Inner Mongolia, Mongolian identity is spatialised, associated with extensive forms of movement and open landscapes, in binary opposition to the agrarian Han Chinese, who are associated with walls and enclosures (Williams 2002). Through its wide-ranging grazing habits, which were incompatible with recent grassland management policies such as privatisation and fencing, the horse embodied an extensive way of engaging with land that is regarded as characteristically Mongolian. The politically safe language of horse breed conservation thus enabled Mongols to mobilise in opposition to the restrictive policies of state environmentalism and to champion a Mongolian, ‘nomadic’ way of engaging with the land that has been stigmatised by the modernising Chinese state.

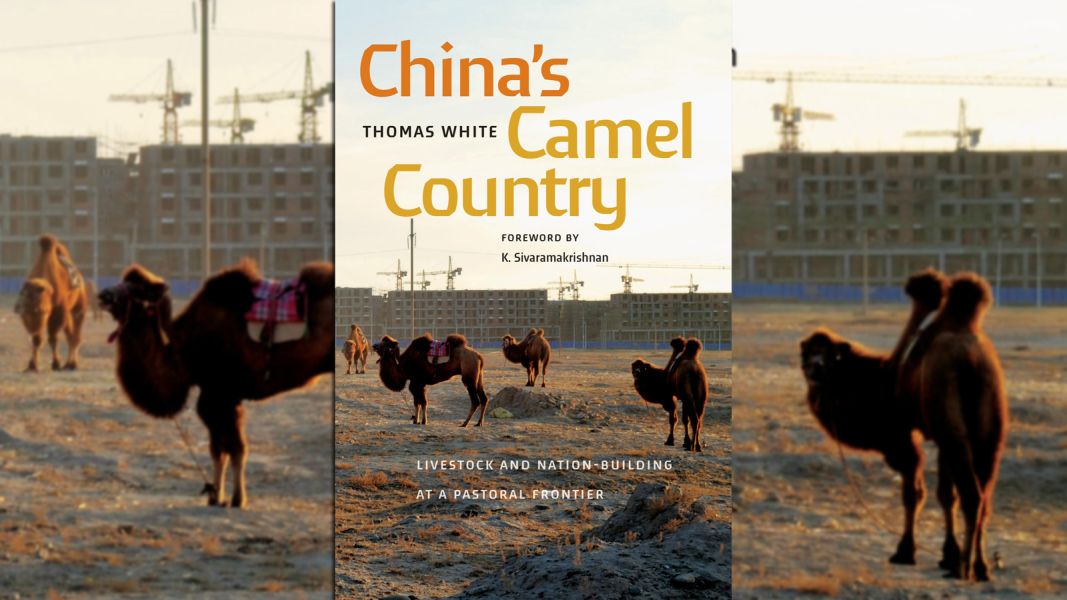

China’s Camel Country

My new book, China’s Camel Country: Livestock and Nation-Building at a Pastoral Frontier (White 2024), discusses another form of beastly politics in Inner Mongolia, and its relationship to shifting ideas of nationality, place, and culture. At the turn of the millennium the population of camels in Inner Mongolia’s Alasha region was less than one-fifth of its size at the beginning of the reform era, and local and national media began to discuss their impending extinction. This rapid reduction in numbers was in part due to their obsolescence as a means of transportation and to the boom in cashmere that began in the 1980s that led to herders selling their camels to concentrate on goats. But it was also down to the state’s destocking policies and a policy of grassland privatisation that has proven particularly ill-suited to this wide-ranging animal, which is herded in a highly extensive manner, being largely left to its own devices for much of the year. Around the turn of the millennium, prominent local officials derided the animal’s backwardness and its lack of economic value. But as the state’s environmental policies pushed many herders into the town, local Mongols saw in the declining population figures for the camel a clear index of culture loss.

In 2005 a group of local Mongol elites (retired and serving officials) founded the Alasha Camel Society, dedicated to the conservation of this animal. Officially a nongovernmental or ‘popular’ (民间) organisation, this society succeeded in gaining local exceptions from the destocking policies for the Alasha Bactrian camel and having this breed listed as a protected genetic resource at the national level. Certain camel-related practices have also been listed as part of China’s national intangible cultural heritage. More recently, the camel has come to be promoted by the local government as a central pillar of its rural development strategy, which now emphasises the production of camel milk for sale to urban consumers across China.

In articulating a defence of camel husbandry through various reports and submissions to the local government, Mongols in Alasha made strategic use of long-established tropes linking minorities and animals. They contrasted the intense feeling (感情) that herders had for their camels with the labour of agriculture, where this intensity of feeling was said to be absent. Such was the extent of this feeling, they claimed, that if herders were deprived of these animals, there was the risk of social unrest. Here, these defenders of camel husbandry played on the state’s fear of instability in a strategic borderland, as well as deep-rooted Chinese understandings of minority relations with animals. Even as camel dairying began to be mechanised in the mid 2010s, the affective bonds between Mongols and their animals were considered: camel-milking machines were designed with inbuilt speakers capable of playing a selection of the Mongolian ‘long songs’ (urtiin duu) that are supposed to encourage milk let-down in camels. Mongolian culture was thus understood as a more-than-human phenomenon (see also Hutchins 2020).

Interpretations of camel-related heritage were also shaped by the representations of minority–animal relations that were circulating in Chinese culture in the early twenty-first century. A fertility ritual involving camels was officially inscribed as heritage and came to be understood by Chinese anthropologists as an example of ‘camel worship’ (骆驼崇拜), which manifested local Mongols’ ‘simple philosophy of respect for nature’ (崇尚自然的朴素哲理) (Wu and Sheng 2016). Such interpretations downplayed the Buddhist aspects of these rituals and their relationship with a range of rituals directed at the increase of household fortune. Instead, the primitivist figure of the animal-worshipping minority was superimposed on these practices. While such interpretations worked to counter scientistic discourses that stigmatised pastoralism as backward and environmentally destructive, they were often at odds with the understandings of local herders.

However, unlike the horse, the Alasha Bactrian camel cannot straightforwardly stand for the Mongol nationality. Camel herding is largely confined to Gobi regions and not all Mongols hold camels in high regard. The Alasha Bactrian camel thus had a distinctive local identity. This was reinforced by the convention of identifying breeds with certain places. Imagined as breeds, livestock biodiversity does not neatly map on to the diversity inscribed into the Chinese nationality classification system, with its 56 nationalities. Instead, it corresponds more with a political economy in which administrative subregions are encouraged to compete, particularly in terms of cultural branding (Oakes 1999). Such competition is evident in Inner Mongolia, where Mongols in Urad Rear Banner, which borders Alasha to the east, have mobilised around the conservation of what is said to be a locally distinctive ‘Gobi red camel’ (戈壁红驼) and its associated cultural forms.

Livestock conservation, which began as a project of minority cultural survival, was thus shaped by the spatial contours of the Chinese state and political economy. It was possible to gain a degree of local state support for camel husbandry because it could be made to fit with prevailing ideas of local cultural branding and comparative advantage. Local Mongol advocates for camel husbandry had to adapt their understandings of culture such that ‘Alasha camel culture’ was not the exclusively property of Mongols but was also practised by local Han Chinese (and Hui). According to one of those involved in camel conservation, culture consisted of the ‘survival skills’ (生存的技术) required in a particular environment and was not the mark (符号) of any particular nationality. Such understandings are in line with nation-building imaginaries in the Xi era. Recent anthropological work in China (see, for instance, He 2020) celebrates camel culture as an example of the ‘contact, exchange, and mingling’ (交往交流交融) between nationalities that is promulgated as part of ‘second-generation’ nationality policies (Roche and Leibold 2020).

The increasing circulation of ideas of the Silk Road (丝绸之路) in China, particularly in the wake of the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, has also strengthened the camel’s association with imaginaries of exchange and interaction between peoples. In the words of one local scholar, ‘It was camels that travelled the Silk Road, the Porcelain Road, the Tea Road, bringing agrarian and nomadic civilizations together and helping them to blend’ (Liu 2017).

The Post-Ethnic Animal

On the one hand, then, the defence of camel herding in Alasha involved the deployment of tropes that identify minorities with animals. Such tropes have a very long history in China and were once even built into the written language itself. Their continued resonance, however, is not simply the result of a political centre requiring a denigrated barbarism to burnish its claims to civilisation. Instead, the identification of minorities with animals in the twenty-first century has been used by both minority and Han Chinese writers and filmmakers to critique the ecologically and culturally destructive developmentalism espoused by that political centre, and to contest assimilatory logics.

However, nonhuman diversity is not isomorphic with the twentieth-century modernist scaling of culture represented by China’s nationality classification project. When it comes to minorities in China, animals are symbolically excessive. Alasha’s camels came to enjoy protection as a local breed and their conservation has reinforced emergent conceptions of a post-ethnic local culture, in which differences between nationalities are de-emphasised. This animal also has certain symbolic affordances that have become prominent in the age of the BRI. Where once camels were hallmarks of the backwardness of a remote minority region, now they are celebrated for enabling Eurasian connectivity and cultural intermingling. Camels remain in Alasha, but their associations have begun to shift. Animals, then, can be equivocal vehicles for projects of minority cultural survival in today’s China, transforming those cultures even as they are invoked to conserve them.

References