The Involution of Freedom in Yabi Subculture

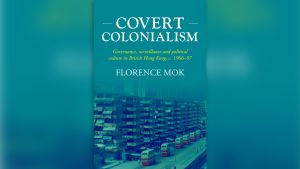

During the early reform era one could argue that a liberal proto-counterculture was developing in the cosmopolitan undergrounds of Beijing and Shanghai, as China converted to capitalism and university students tested the limits of Western democratic practices. In the decade of market transformation that followed the June Fourth Incident, such experiments did not have a chance to bloom, as it was a time when ‘money ruled everything, morals died, corruption burgeoned, [and] bribes were bartered’ (Nathan 2001: 48). Despite this turn of events, a plethora of subcultures (亚文化 yawenhua) gained traction with the proliferation of the internet after the turn of the millennium, attracting much academic attention. While overtly political activities such as protests, demonstrations, and other gatherings have been strictly prohibited under the Xi Jinping administration, Chinese youth—particularly the post-1990 generations—have been able to find ‘like-minded people’ (同温层 tongwenceng) online, through chat groups, forums, and other social media spaces.

As the internet grew to become an essential service for everyday activities, subcultures began to flourish. This led to the ephemeral social media collective resistance of spoofing (恶搞 egao), through which netizens digitally satirised Chinese censors using clever homonyms (Nordin and Richaud 2014). However, the carnivalesque egao quickly devolved into dispirited viral meme-based hashtag subcultures such as ‘loser’ culture (屌丝 diaosi), ‘mourning’ culture (丧 sang), and the ‘lie-flat’ generation (躺平 tangping). Such online subcultures, without aesthetic communities through which to alleviate alienation, are a digital release valve for China’s ‘involuted generation’ (Liu 2021), whose primary commonality is their disaffected spiritual ennui in an involutionary (内卷 neijuan) response to ‘an intense and fast-paced corporate and social culture in contemporary China’ (Zhang and Li 2023: 49). These yawenhua coalesce around cultural representations that are pessimistically masculine; diaosi literally translates as ‘penis hair’; and memes of Sad Toad (a reinterpretation of Pepe the Frog, which has come to be used as an alt-right symbol in the West) and Paralysed Geyou (an unemployed, broken character from the popular sitcom I Love My Family [我愛我家]) have become mainstream associations with dissatisfied youth (Voroneanu 2022).

Offline, yawenhua range from class-based aesthetic communities such as the shamate (杀马特)—a vibrant subculture (popular especially in northeast China) of migrant teenagers who dress up like anime-punk rockstars or what Americans would call ‘emo teenagers’—to trend-based yawenhua like ‘three traps’ (三坑 sankeng), referring to the Preppy, Lolita, and Hanfu (汉服, ancient Chinese) styles, as well as the ‘national-tide’ (国潮 guochao) appreciation of domestic brands. This essay focuses on the highly controversial yabi (亚逼) subculture, which originated in China’s urban club and underground music scenes in 2019. The term comprises the characters ya (亚 Asia, inferior)—that is, the ‘sub’ in subculture—and bi (逼 force), which is a derogatory, diminutively feminine curse often used in compound words like shabi (傻逼, idiot) and zhuangbi (装逼, poser, fake). Together, yabi literally means ‘subcultural c*nts’—a contested term that is used by those supporting the status quo to identify and insult anything that appears threatening to mainstream culture, and on the flipside, as a signal of subcultural resistance under a heavily repressed authoritarian regime.

Aesthetically, yabi is a post-internet hotchpotch, influenced by (but not limited to) punk, otaku, e-girl, cybergoth, K-pop and J-pop, Asian babygirl, hip-hop, rave, and techno styles from across the globe. This essay seeks to elucidate the yabi phenomenon through the sociopolitical conditions that gave rise to it, as well as to provide a historical analysis that traces a feminist genealogy of this subculture in its various incarnations throughout a heavily patriarchal imperial and modern China. I first provide analysis of how and why women have become the main defenders of the term, perceived as derogatory by the forces of the status quo. By situating the yabi within subcultural theory, I seek to illuminate how this subculture exercises subtle forms of resistance to China’s ‘positive energy’ (正能量) narrative through self-styling and musical taste. I expand on this resistance by tracing a lineage of supernatural femininity from which the yabi aesthetic implicitly draws, which has been present throughout imperial and modern Chinese history. Counter to critiques of the yabi’s incoherent and superficial style relative to their misunderstood position as middle-class urbanites, I propose that the yabi exemplify the feminine supernatural reborn digitally, as an attempt to heal the present-day involuted generation, who are caught by unrealistic, uninspiring, and untenable societal pressures.

In Defence of Yabi: Aesthetic Controversy as Public Debate

In the dense, murky, and 404-ed depths of the Chinese internet, causality and meaning have become increasingly unfixed and unpredictable as personal expression necessarily adapts to censorship. New homonyms are created every day to circumvent blocked words; recorded videos are edited to evade automated searches; fonts used for captioning are altered and skewed. The contemporary technoscape has drastically shifted modes of production and consumption and, following post-pandemic social fallout, many youngsters across China live their corporeal existence mediated by online identities. As public discourse is permitted only when the topic is deemed non-political, controversy over yabi subculture can be understood as an exercise in public debate by China’s youth in response to the conservative nationalist values of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (Su 2023; Zhang and Li 2023).

Although, when questioned, many citizens would likely insist on the apolitical nature of their choices in just about every aspect of life, such insistence can be understood as self-defence against the potential consequences of inadvertently criticising the ruling party. For example, when asked about the political nature of the shamate subculture, Luo Fuxing (the godfather of shamate) responds:

Shamate might have been invented by workers, but exploitation isn’t intrinsically related to aesthetics—we were never trying to wage class warfare … Free speech can’t be treated as a basic freedom. It’s too difficult to realise in China, because speech has the power to harm people. (Zhang and Chang 2021)

Therefore, public displays of one’s politics must be exercised non-verbally; with reservations about mainstream positive-energy narratives, the yabi express such rifts between expectations and reality aesthetically. In a 2022 article titled ‘Yabi Is a Dream, Anyone Can Dream It’ (亚逼是场梦, 谁都可以做) published in the online alternative culture magazine Bie De (别的), staff writer ‘Randy’ interviews Liang Qian, who grew up middle class in a first-tier city, surrounded by friends ‘who had private jets at home’. Liang graduated top of her class but has since struggled to find a suitable career, bouncing from academia to nonprofit to corporate work. After her father died, her primary focus in life shifted to taking care of her mother. Beyond that, her outlook on life is typical of the tangping mindset: the country’s dominant narratives of ‘joining a big factory, earning a high salary, and buying a home in a first-tier city’ are increasingly out of reach, resulting in the involutionary phenomena of diaosi, sang, and tangping youth cultures (Chang et al. 2021; Su 2023; Voroneanu 2022; Witteborn and Huang 2016; Zhang and Li 2023). With the ‘get rich quick’ possibilities of the early reform period long over, the ambitions of what was once the country’s middle class have produced a consumer class ‘lumped at the upper end of the spectrum’ (Sethi 2018: 57)—those who were able to gain from Deng Xiaoping’s ‘let some people get rich first’ blessing. The heirs of this limited intergenerational wealth now make up the yabi.

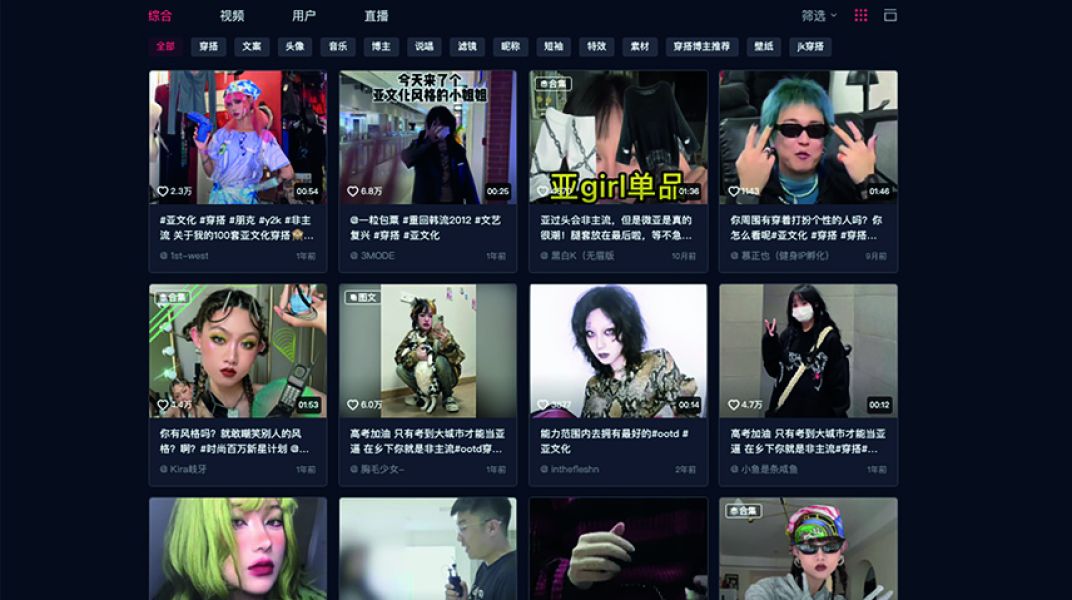

To identify oneself as belonging to a subculture, a group forms to resist, reappropriate, and redefine what has been deemed undesirable by the hegemonic order. Those who identify as yabi are not the first group of people to take on a previously offensive term in an act of counter-hegemony (Huang 2016: 42) and as ‘resistance to imposed socioeconomic norms and expectations’ (Witteborn and Huang 2016: 143). In their 2014 study of egao, Nordin and Richaud (2014: 49) note that ‘repoliticization also involves depoliticization, reflecting the complexity and ambiguity of the relationships they negotiate’. To repoliticise oneself through depoliticisation explains the reappropriation of such a derogatory word as bi by a yawenhua activated by mostly feminine and androgynous presenting subjects. Although yabi is not gender specific, most yabi discourse online features women trying to provide a palatable definition, address the criticisms, and show off their unique take on the look. A basic search on the homepage of social media platform Xiaohongshu features 91 of 100 thumbnails of young female-presenting yabi and products geared towards a femme yabi consumer. The yabi aesthetic traverses not only a cultural but also a temporal and anthropomorphic supermarket of representation: hanfu, animal appendages, and throwback Y2K accessories combine perfectly to create a #ootd (outfit of the day). Their style becomes a method of alternative resistance turned inward, where, according to Luo Fuxing, ‘aesthetic freedom is the starting point of all freedom’ (Zhang and Chang 2021).

Through her examinations of culture via elemental cosmologies, media theorist Yukio Furuhata notes how contemporary critical discourse has prompted cultural producers to revisit and remix myths as their spatiotemporal specificities have been unfixed throughout the recent discourse of the Anthropocene. According to Furuhata, our present modernity collapses categorical distinctions between human and geological history, as humans have only recently become a significant environmental agent driving climate change. Requiring us to consider both Earth’s natural history and the human history of world-building together, Furuhata (2022: 73) argues that this collapse in distinction ‘prompts us to think about another temporality: that of mythology’. As the yabi aesthetic is not only reviving but also reinventing mythology in an aestheticisation of involutionary tendencies, the yabi can be understood as a response to the Anthropocene’s challenges in the context of Chinese governmentality and censorship. Such collapsing of spatiotemporal signifiers and reinvention challenge ‘the categorical distinctions between the deep time of geology and the historic time of human civilizations, between geohistory and world history, and between nature and culture’ (Furuhata 2022: 73).

For example, Shanghai’s underground club scene is a community of artists, musicians, designers, producers, and influencers who gather regularly at hybrid events that are simultaneously performance art, social practice, and nightlife. One prominent underground party collective is EVO, whose founding member, Wu Youyi, stated in a 2020 interview with Subtropical Asia that their aesthetic is inspired by visual kei (underground Japanese glam metal of the 1980s) as much as it is by classical Chinese aesthetics and literature, with contemporary manifestations of Chinese ‘traditional ghost culture’. EVO’s style is situated within a broader cultural trend of remixing that the collective has seen flourish in China since 2018, where youth cultures have been creating new visual systems made up of fragments, ‘yet to be defined’. With regards to the yabi, Wu believes that the initial reactionary responses to the term have led to misunderstandings and insincere adoptions of the look, while overshadowing any ‘rational discussion behind this phenomenon’. Another netizen, taoagou00, responded to the phenomenon and virulent backlash in her 2021 vlog titled ‘I Am Yabi’ (我是亚逼). Stylised underneath a single spotlight with computer-generated filters to create a dark and misty internal world, she first itemises her #ootd: counterfeit high-street–style shirts, a mourning graffiti sweatshirt, spliced beggar-style wide-leg pants, distressed sneakers, Yamamoto-style fisherman’s hat, dyed hair, reflective guochao shoulder bag, and an Instagram-sought frog pendant. The camera swoops around to highlight her adornment while her voiceover narrates:

I’m a yabi, I embrace all kinds of niche and weird subcultures to make my own unique style. This is an expression of my thoughts. The point is not what I think, but how I am able to express it. Behind every metal chain is an imprisoned roar. I use photos to record my pain and struggles. What the camera records is just a concealment of my soul. My twisted limbs are an expression of my repression. The only antidote is music, but I never listen to hip-hop, only trap, because too many people are into hip-hop now. (taoagou00 2021)

Moving into the realm of music critique, she types a post into her phone that the viewer sees onscreen: ‘Hi everyone. Something bad happened, I don’t even want to talk about it. So annoying, I’m so numb, nevermind. Say no more, my life has taken a turn—’ only to be interrupted by a man’s voice: ‘Daft Punk has disbanded!’ ‘Daft Punk?’ she thinks, and quickly searches ‘What is Daft Punk?’ Her response to what seconds earlier was completely unknown is, ‘What! Daft Punk disbanded? My youth is over!’ and breaks into tears for a few seconds before moving on to text with friends, whose opinions on yabi are that the style is chaotic, messy, ugly, and tacky. Finally, she concludes that hip-hop and rock music are just distractions, that ‘folk music is the true music’, before signing off in a flash of wildly different #ootds.

Although taoagouoo’s video is just over a minute long, she traverses various taboo subjects underneath consumer-class superficialities of clothing and popular music. Veering between sincerity and irony, she reveals that being yabi is a way of expressing her repressed, concealed soul; that traumatic life-altering experiences are not acceptable social media content; and, perhaps most profoundly, that folk music—in solidarity with the migrant class—is the ‘real music’ (民谣才是真正的音乐). While ‘I Am Yabi’ can be categorised as a lifestyle vlog, the subtleties it contains speak to how yawenhua, with yabi at the helm, are a collective act of resistance against the status quo. In another netizen’s 2020 vlog, ‘What Is Subculture? “Yabi” Isn’t “Crass/Unfashionable*”’ (什么是亚文化? ‘亚逼’不是‘土*’), BBQ-Qiu (BBQ秋) argues that yabi is a neutral word, that it means ‘subculture enthusiast’ (亚文化爱好者). As an enthusiast—or, more literally, a ‘subculture lover’—embracing other online alienated meme-based yawenhua who do not have such a prolific and fashionable aesthetic in the real world, the yabi are in effect signalling for others to join them in finding aesthetic freedom.

From Goddesses and Fox Spirits to Holding up Half the Sky

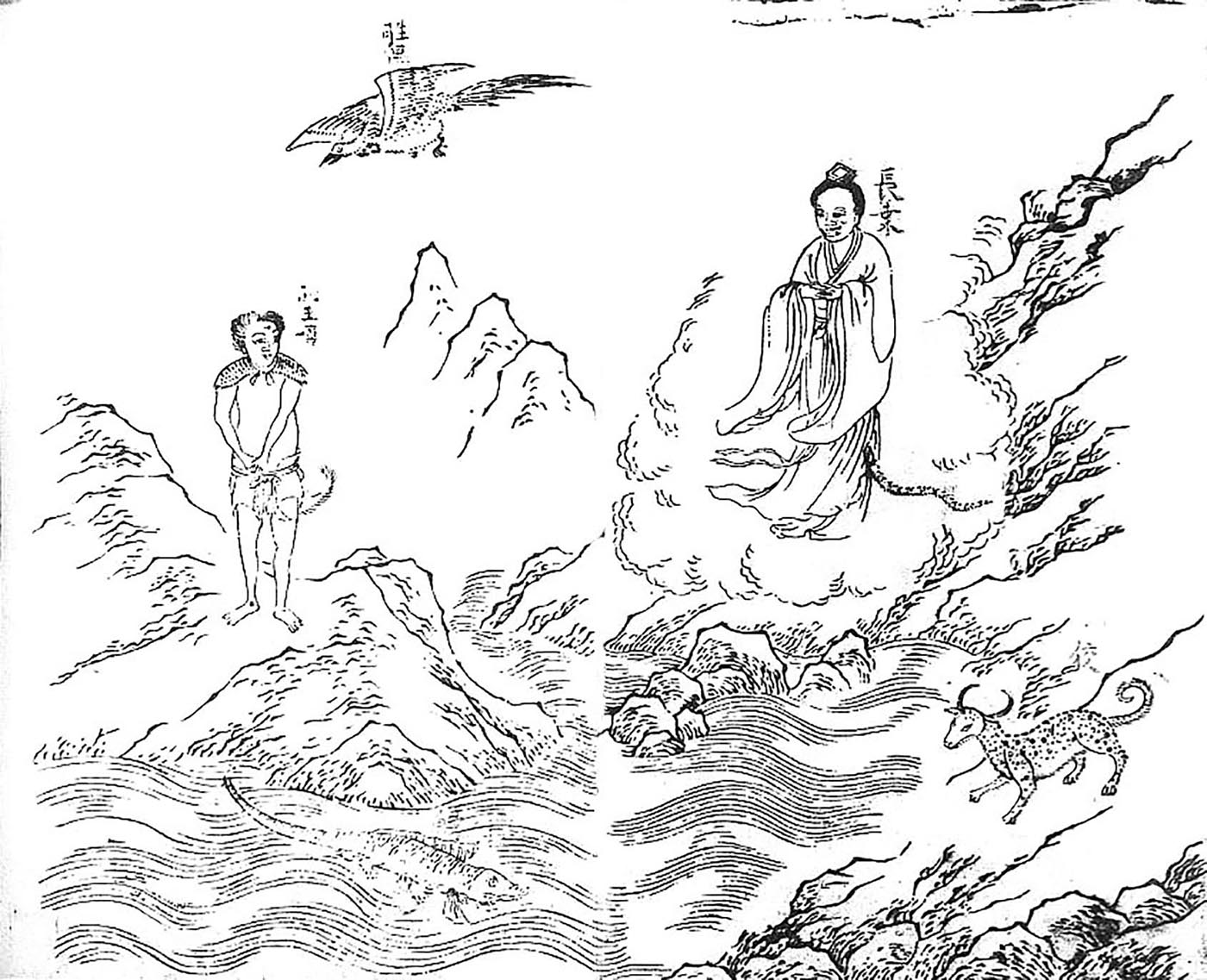

Reaching back to the ancient cosmographical text The Classic of the Mountains and Seas, in which the female gender was asymmetrically prestigious compared with its male counterpart (Birrell 2002: 29–32), the feminine supernatural can be traced throughout China’s formative epochs of state, nation, and revolutionary party-building. Although contemporary Chinese society still follows patriarchal neo-Confucian values in which women are subservient to men, studies of premodern China show that this was not always the case. Dating back to the Warring States period (476–221 BCE), The Classic of the Mountains and Seas is a cosmographic survey describing more than 500 mythical creatures, 550 mountains, 300 rivers, 95 foreign lands and tribes, and hundreds more flora, medicines, metals, and minerals (Strassberg 2002: 3). Iteratively and collaboratively written, it incorporates numerical, astronomical, geographical, and environmental systems, along with a bestiary of mythical creatures to create a totalising assemblage of the world before the practices of modern cartography. Empirical facts and myths are blended within a geographical framework to organise ‘diverse information about the world in an effort to define a more systematic pattern of totality as a model for a centrally unified China’ (Strassberg 2002: 9). In other words, various orders of knowledge are systematised to assimilate the unknown. Recalling Furuhata’s claim of the Anthropogenic collapse of space and time, body and politics, the yabi remix and reinvent personal aesthetics that defy historical and spatial continuity as a means to ‘challenge categorical distinctions’ that govern the status quo in present-day China.

Historian Anne Birrell (2002: 2) notes how, compared with other classical texts to come, the inclusion in The Classic of the Mountains and Seas of many female goddesses and mythical creatures—notably, the Mother Goddess (女娲 Nüwa), the Spirit Guardian Goddess (精卫 Jingwei), and the Mother Queen of the West (西王母 Xiwangmu), who lived, ruled, and transformed with autonomy in the natural world—‘implicitly constructs a gender asymmetry in which female is accorded a privileged status’. For instance, the Mother Queen of the West’s power is revealed not through her relation to humankind, but through her design and control of the cosmos. Later Han Dynasty (202 BCE–9 CE, 25–220 CE) texts, Biographies of Exemplary Women (列女傳) compiled by Liu Xiang and Lessons for Women (女誡) by Ban Zhao, both position women as subordinate to men.

Gender roles defined through patriarchal Confucian ideology became increasingly normalised when the Han Dynasty court officially adopted Confucianism into its education and political systems. As argued by Frederick Engels’ ethnographic and historical reconstruction of Western feudalism (Sacks 1983) and applied to Chinese imperial society by Birrell (2002), it was the feudal class and property system that eroded pre-class egalitarianism between genders. Compared with a Western biological gender binary, Chinese linguistic construction did not have an equivalent gender construct based on sex until the twentieth century; the term funü (妇女, woman) relayed a woman’s personhood as a social construct via kinship and ritual—how she moved through the world in relation to men. As made clear through the practice of foot-binding, this movement was restricted and reflected in literature, in which men travelled as scholar-gentry and women played the roles of mother, wife, daughter, relative, maid, concubine, and prostitute.

Although the Confucian doctrine ‘men are superior and women are inferior’ (男尊女卑) restricted the role of women to not just earthly but also domestic realms, their affinity with the supernatural was maintained through literature. From the sixteenth-century Ming Dynasty classics Journey to the West (西游记) by Wu Cheng’en, an episodic huaben (话本, vernacular short story) following the journey of a Chinese monk’s pilgrimage to India, and Lanling Xiaoxiao Sheng’s The Golden Lotus (金瓶梅), which chronicles the sexual exploits of three women around the lustful, corrupt merchant Ximen Qing, numerous female spirits, ghosts, and fairies serve as adversarial plot devices. In the succeeding and final Qing Dynasty of China’s imperial history, sexualised and supernatural femininity became a paradigm through Pu Songling’s 1679 collection of 500 supernatural short stories, Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (聊齋誌異), which repeatedly featured fox spirits (狐狸精) who assumed the guise of seductive temptresses. While some of the tales end happily with fox spirits falling in love with the man of the house, the typical story has an honourable man falling under the fox spirit’s sexual spells, draining him of his life force.

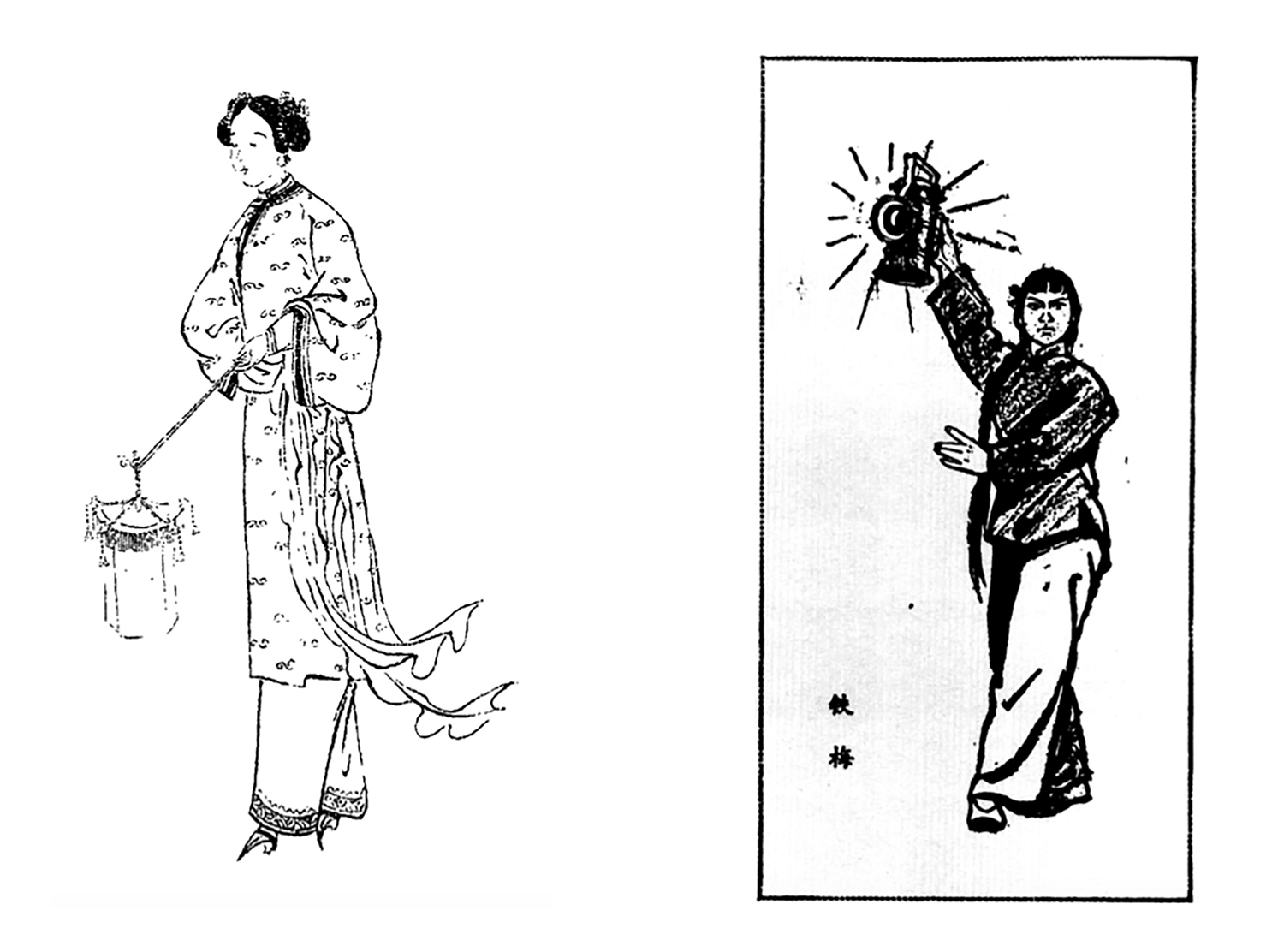

At the turn of the twentieth century, supernatural femininity moved off the page to play a prominent role in the patriotic but wildly superstitious Boxer Rebellion (Terrill 1984: 272–73). While male Boxers collectively took part in mass spiritual possession, martial arts, and qigong (气功, breathing exercises) believed to help achieve invulnerability against modern weaponry, their female auxiliary fighters, the young women and girls who made up the hongdengzhao (红灯照, Red Lanterns), were said to be able to leave their bodies, fly, set fire by will, control the wind, heal wounds, and reanimate the dead. Their prepubescence deemed them supernatural, while all other women were ostracised for their uncleanliness; menstrual and foetal blood, urine, nakedness, and female pubic hair were all considered unclean, hindering the efficacy of the Boxers’ magic powers during battle. Female skin, pubic hair, and even women themselves were hung up or nailed to the exterior of targeted buildings to ward off the Boxers’ attacks (Cohen 1997: 132–39).

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty, the 1915 New Culture Movement’s determination to move society forward away from the old culture sublimated the animistic feminine supernatural and sexuality into two new modern archetypes for a brave new Republican world: the xin nüxing (新女性, New Woman) and the modeng gou’er (摩登狗兒, Modern Girl). First appearing in the anti-imperial literature of the May Fourth Movement, the New Woman quickly became a symbol of the nation’s anti-traditionalist revolution, making funü an outdated term. While the New Woman was ‘educated, political, and intensely nationalistic’, her counterpart, the Modern Girl, was ‘a sinister and dangerous figure—a distant siren, luring the unwary and ill-prepared male subject to his ultimate demise’ (Stevens 2003: 83–89). Along with literature, the burgeoning Shanghai-based film industry, as well as the proliferation of print media—particularly the popular 1930s women’s magazine Ling Long (玲瓏, Exquisite)—disseminated this dialectical female fantasy into popular consciousness. Ling Long published articles and stories about the New Woman in the front and ran advertisements and movie showtimes depicting the Modern Girl in the back. Films such as Labourer’s Love (dir. Zhang Shichuan, 1922), Love and Duty (dir. Bu Wancang, 1931), and The New Woman (dir. Cai Chusheng, 1935), contributed to the formation of ‘Woman’ as a symbol of modernity—a femme fatale, a praying mantis (Stevens 2003: 92)—to whom anxieties and fears could be ascribed. Akin to Western feminist critiques of the double productive and reproductive burden placed on women, the fact that such fears about modernisation, female emancipation, and foreign infiltration were exorcised through cultural production is not surprising during a period that included two world wars, the Sino-Japanese War, and the Civil War.

The history I have traced is one through which the feminine subject has been demonised, modernised, and instrumentalised in various myths up to the CCP’s rise to power. Effective immediately in the People’s Republic of China, nüxing was re-gendered back into funü, emphasising the female peasant-proletarian as revolutionary warrior (Kim 2020: 634; Li 2020: 76). In combining ancient elements of folk legend with proletarian communist propaganda, the feminine supernatural became sublimated into the selfhood of the masses as revolutionary supernatural fervour. Whatever divine attributes, animistic energies, and sensorial powers were previously bestowed on to women were now funnelled into the CCP’s singular purpose. ‘Women can hold up half the sky’ is a well-known Maoist slogan popularised to activate 100 per cent of the workforce (Sun 1974; Zhong 2011). ‘The White-Haired Girl’ (百毛女), a legend from Hebei Province, is exemplary of a folktale turned feminist communist propaganda, passed on through short stories, songs, yangge (秧歌, folk dance), and stage plays, eventually reaching the Communist Party in Yan’an in 1944 (Kim 2020: 640). The protagonist, Xi’er, is a young woman who flees after being raped and impregnated by her landlord into the mountains, where she gives birth in a cave, only to lose her baby. Hair and skin white from malnutrition, she is discovered by villagers who believe her to be a goddess and champion her to lead a revolt against the landlord. After a successful uprising, the story ends with Xi’er restored to her pre-supernatural form, proudly back in the fields with the farmers. First performed during the Chinese Civil War, the story was adapted into a feature film in 1950 (dir. Wang Bin and Shui Hua), and as one of Jiang Qian’s revolutionary model operas during the Cultural Revolution.

Re-emerging during the Cultural Revolution, the Boxer Rebellion’s hongdengzhao now transformed into the hongweibing (Red Guards, 红卫兵). Symbolic resonances in their names, hongdengzhao and hongweibing, their self-styling (head-to-toe red), and their rebellious, youthful spirit were the perfect communist gimmicks to mobilise thousands of teenagers to cleanse society of ‘the Four Olds’. Further radicalised in 1973 via the Anti-Confucian Campaign led by Jiang Zemin, the hongdengzhao were heralded as a symbol of female emancipation in a patriarchal society. The campaign targeted ‘bureaucratism, abhorrence of physical labour, and the subordination of women’ (Cohen 1997: 270), but it was undoubtedly a grasp for personal and ideological power by Jiang. In a subtle reference to The Classic of the Mountains and Seas, the legend of hongdengzhao leader Lin Hei’er reappropriated as propaganda during the Anti-Confucian Campaign reads: ‘Mountains may be levelled and the seas may be emptied but the red lantern of revolution will never be extinguished!’ (Liu and Xu 1975: 77).

An Involution of Aesthetic Freedom

In my historical tracing of the feminine supernatural throughout Chinese history, subcultures had not yet been conceptualised, recorded, and studied, as the country underwent many eras of instability and upheaval. As an academic discipline, subcultural studies has its roots in theorising by Chicago School sociologists in the 1920s; subcultural analysis was not used in the Chinese context before the advent of the internet. Instead, disenchanted youth who lived through Mao Zedong’s reign and into the failures of the prodemocracy movement were conceptualised through the lens of popular culture (Link et al. 1989, 2002). Nevertheless, there are plenty of examples of what could arguably be considered subcultural activities in Maoist China—for example, in hand-copied ‘underground’ pulp fiction during the Cultural Revolution (Link 1989: 18–36) and, at the start of the reform era in 1979, when a group of painters who named themselves Xingxing (星星, Stars) unofficially exhibited oil paintings made in secret during the Mao years outside the National Art Museum in Beijing as a call for freedom of expression (Gladston 2013: 21–22). These glimpses of rebellious cultural production signal to the subversive impulses of a counter-hegemonic ‘bottom-up’ subcultural perspective (Zhang 2022) ever present in the face of repression. They also portend a defining element of subculture: the desire of subalterns to demand a public appearance (Anderson 1994).

At its base, subculture has been defined as a group cultural identification with deviant behaviour due to social problems within society, in resistance to mainstream cultural values (Haenfler 2014: 2–5). The performance of subculture through self-styling is how one finds their chosen kin, while simultaneously rebelling against the status quo by way of aesthetics. During the Mao era, when revolutionary socialist realism depicted only one culture—the proletarian subject under Mao—anyone who was deemed a vagrant, counterrevolutionary, or member of the ‘dangerous classes’ was captured and subjected to forced labour and thought reform (Smith 2013). Thus, subculture was severely repressed until the 1990s, when China’s transition into a market economy produced a consumer class who had extra income to spend and who could, via international trade, make contact with the rest of the world. With the internet, this contact not only provided access to a global fenggechaoshi (风格超市, cultural supermarket)—or the ‘supermarket of style’ in subcultural theory—but also created a virtual space where yawenhua could form digitally before gaining the courage to present publicly.

Recalling classical Chinese literature and aesthetics in which female figures like the snake-bodied Nüwa, her bird-daughter Jingwei, and the Xiwangmu (who had a human body, a leopard’s tail, and tiger-like fangs) thrived, the yabi reactivates ancient cosmographical meaning-making in subtle resistance to the CCP’s authoritarian hegemony. At first glance, such a predominance of women may speak to a female-targeted fashion industry controlled by the technological gaze, one that cannot but replicate the gender inequity of the real world as a manifestation of surplus male desire as mengyan (梦魇, incubus) energy, the feedback of China’s One-Child Policy. However, I propose that a more nuanced reading of the yabi’s social function is necessary: the yabi cannot be understood and dismissed as simply young urbanites shopping and styling themselves through spiritual ennui. How does the slippery yabi aesthetic function in contemporary Chinese society and, in the identification of their social function as yawenhua, what do the yabi want?

In ‘A Quick, Dirty Guide to China’s Controversial New Subculture: The Yabi’ published by the popular online culture and lifestyle magazine Radii by Beatrice Tamagno in 2023, one young male-presenting Shanghainese resident speaks for the mainstream, stating: ‘Instead of thinking critically about society and forming their own opinions, yabis in Shanghai only worry about dressing themselves in exaggerated and colourful ways.’ This is a common misconception, according to vlogger Etsu Kinugawa 鬼怒川悦. In her 2022 Bilibili vlog, ‘Am I Yabi? I’m so Yabi? Reflections of an OG Subculturalist’ (我是亚比/亚逼?我好 亚b?老亚文化人的思考), Kinugawa claims that in the wake of yabi subculture over the past few years, ‘outstanding’ cultural production—music, fashion, literature, and even film—by yabi is now being recognised and its creators are being approached by multi-channel networking agencies. During her 13-minute video, she even suggests that the yabi aesthetic is rooted in punk, as a ‘culture of the common people fighting for their rights, which is a good thing’. Not only does this assertion resonate with taoagou00’s statement that the only real music is folk music—that is, the music of the common people—Kinugawa also manages to communicate this message without using red-flag words like ‘activism’ or ‘solidarity’.

That yabi came out of hip-hop or techno music scenes is telling, as both are cultural imports with their own vast genealogies across the globe, and long cycles of adaptation, appropriation, and transformation. There are different origin stories of the term, but all point to independent music scenes. In the most accredited version, one netizen recalls that it was during techno music label Cloak’s one-year anniversary party in 2019 that a user named E’wen Xun (埃文熏) made insulting comments in the chat-stream on Bilibili. Before being called out and booted off, he wrote: ‘Yabi [Asian c*nts] still rely on mocking social hierarchy to feel superior’ (Suslik 2021). From there, the term went viral via the music community, crossing over from cyberspace into studios, concerts, clubs, and parties. Kinugawa advocates for a new term, as she believes yabi to have originated from Chinese hip-hop, where rappers used it as a derogatory reference to other yawenhua. Music producer GG Lobster brings the term back to underground techno, where yabi was used to describe the ‘new-club’ genre DJs and producers, and also suggests laying the term to rest in favour of xinbuzu (新部族, neo-tribe)—a term he undoubtedly sourced from post-subcultural theory, which is defined as ‘diffuse collections of people that gather intermittently, primarily to have a good time, and share some sense of collective identity … but do not share much in the way of an underlying identity or ideology’ (Haenfler 2014: 11). The zu (族) in Lobster’s xinbuzu is used in various compound words to mean clan, family, race, nationality, ethnic, and social group, circling back to a cosmographical application of identity construction in what sociologist Phil Cohen (2004: 71) calls a ‘magical’ expression and resolution ‘of the contradictions which remain hidden and unresolved in the parent culture’.

In such an iterative and continuous cycle of self-formation mediated by digital platforms, what the yabi want can be understood as an aggregation of many virtual selves against the actual other—the other-past of its origins and the yabi’s own projected otherness relative to the increasingly out-of-reach positive-energy narratives. By communicating through personal style what is impermissible through words, feelings of alienation expressed online by the ‘curling inward’ involutionary yawenhua—sang, diaosi, tangping—can be transformed into offline communities of tongwenceng. Throughout the mythic genealogies traced in this article, the yabi aesthetic evokes a ‘subcultural enthusiast’ feminine supernatural in continuous flux—one that is in solidarity with the class politics of the common people, of whom they and the other yawenhua are a part. In the present Anthropogenic collapse where doomsday realities of climate disaster and warfare exist in the same space as green-tech miracles and space colonisation, in which positive-energy narratives of better material futures feel further and further out of reach, the yabi is a collective manifestation of mother goddesses and fox spirits signalling to one another that, through aesthetic freedom, there exists other freedoms.

References