Xi Jinping’s Traditional Villages

Over the past four decades in China’s forward march to capitalist modernisation, the nation’s vast urban expansion has been contingent on demolition and relocation. Since Xi Jinping came to power, projects such as the ‘Traditional Village’ heritage scheme have sought to gear development towards a new era in which Chinese heritage sits at the core. Ethnic minority villages across the country are transformed and reconfigured into sites enmeshed with the discourse on capital and profit, but also as mediums for discussing and lamenting lost traditions. This essay delves into how Xi’s ‘Traditional Village’ heritage scheme validates statist views on tradition and Chinese civilisation while at the same time offering new ways of understanding discourse about ethnicity and multiculturalism.

For the past four decades, China has resolutely marched towards capitalist modernisation and rapid economic expansion. To reach its economic goals, demolition and relocation (拆迁) of neighbourhoods have been widespread, leading to unprecedented rates of forced evictions across the country. Somewhat ironically, at the same time that people are confronted with ‘domicide’, and old buildings and cultural landmarks have been demolished and shattered, questions about national heritage and tradition have gained traction (Bruckermann 2016, 2020). Since the outset of the Reform and Opening Up era, state discourse has refashioned and redefined the nation’s values along the divided trajectories of tradition and modernity, strategically deploying ‘civilisation’ (文明) and ‘culture’ (文化) as the backbone of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) political and ideological thought.

Marking a departure from the Maoist dogma of class struggle and socialist values, from the 1980s, public discourse about cultural heritage has been repurposed as a political tool to enhance a rigid ideological nationalism and univocal image of national identity to celebrate, value, and protect a prized heritage. In a past riven by deep political and social disruptions, the now century-old CCP ruled by Xi Jinping seeks continuity and stability through the persistence of ‘tradition’ (传统) in state-led campaigns invoking the commonly stated notion that China has 5,000 continuous years of history. This is a claim repeated in textbooks, mini-dramas, propaganda billboards and banners, and tourist sites across the People’s Republic of China to legitimate and serve the interests of the CCP and unify the nation.

The political significance of cultural heritage is particularly salient for non-Han heritage sites to reinforce China’s doctrine of itself as a multiethnic country. Today, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission recognises a single major nationality (民族), the Han, who make up 92 per cent of the Chinese population, and 55 ethnic minority (少数民族) nationalities. Ethnic minority autonomous regions cover approximately 60 per cent of the country’s geographical terrain and account for a population of 105 million people. Although the Chinese Constitution promises to respect and protect all ethnic minorities’ customs, traditions, and religious beliefs, heritage and tourism policies require heightened political control and surveillance in minority ethnic regions—especially those considered to pose a threat to the country’s border security. The tense relations between Tibetans and Xinjiang Uyghurs and the Chinese State provide a stark reminder of the assertive role that the heritage industry plays in redefining the cultural practices and value systems of China’s diverse ethnic minority populations, with officials weakening or removing grassroots access to cultural heritage and replacing it with state-approved, sanitised images of tradition and local ways of life.

Inland from the politically sensitive border regions, hegemonic representations promulgate images of friendly relations among southwestern China’s ethnic mix. Since Xi Jinping came to power, an integral part of the CCP’s statecraft has been the rigidification of public perceptions of multiculturalism in China, especially through notions of shared traditions. The discourse about tradition is stylised domestically through imported cultural heritage legislation and charters to endorse political strategies that promote a joyous and pristine image of multiculturalism.

Tradition as Cultural Branding

Cultural heritage (文化遗产) and cultural protection (文化保护) have been pivotal to a long string of campaigns under the aegis of China’s state-led development schemes. Over the past decade, since Xi Jinping came to power, projects such as the ‘Traditional Village’ (传统村落) heritage scheme have been emerging across the country. Larger nationwide campaigns, such as the New Socialist Countryside (新农村建设)—a program developed by President Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, and his administration—were amended through the Rural Revitalisation (乡村振兴) program in 2017 under Xi to promote what the Nineteenth Congress of the CCP refer to as ‘urban–rural integration’ (城乡融合) by 2035. The ‘Traditional Village’ scheme aligns Xi’s programs with wider government policy initiatives to eradicate poverty and steer rural citizens working in the informal sector in the cities back to the countryside. As a result, ‘Traditional Village’ heritage sites have been sprouting up across China, promising to extend the national ‘Chinese Dream’ of a middle-class lifestyle to the country’s rural population of 491 million.

The ‘Traditional Village’ scheme attests to the explosive growth of China’s cultural heritage preservation programs in the ‘new era’ of rural revitalisation and modernisation under President Xi (Li 2016). In a country marked by urban expansion and the disappearance of local neighbourhoods, heritage personnel are confident that this ‘new era’ will protect the traditional essence of Chinese villages, while also introducing innovative approaches to minimise the divide between the urban and the rural.

Xi’s cultural heritage schemes are motivated by the economic and political imperatives of capitalism and the market economy. To uphold legible, marketable, and profitable cultural branding, heritage sites are reconfigured and promoted for their unique local speciality, which fits under the concept of ‘tradition’ (Bruckermann 2016; Luo 2018). Key actors such as the local state and market forces work to turn traditions into resources that are useful for both boosting the local economy and strengthening political rule. Ideals about tradition trigger a sense of urgency in Chinese urbanites, who are fearful that China’s serene natural and rural life will be swallowed up by the environmental and moral pollution of cities existing in a state of globalisation-induced disrepair. Heritage discourse promises solutions to such public anxieties.

In my research, I consider how rural heritage sites become mediums through which urban elites express their vision of the nation’s recovery of a lost Chinese civilisation. I studied these processes over 13 months of ethnographic fieldwork between 2014 and 2017 in a place I call Meili, a Dong ethnic minority village in Guizhou Province, southwestern China. The Dong people are an ethnic minority of about three million people who refer to themselves as Kam in the Dong language. They tend to live along riverbanks of the ethnically diverse highlands of southwestern China, including Guizhou, and neighbouring Hunan and Guangxi—a region known for its ethnic diversity, rough terrain, and economic poverty. Guizhou has one of the lowest levels of gross domestic product per capita among China’s provinces and autonomous regions and Meili is in a county labelled ‘poverty-stricken’ (贫困县). The village has over the years become a site for numerous pilot studies, projects, and campaigns to alleviate poverty through the identification and promotion of the area’s uniqueness and efforts to gain heritage recognition.

Tradition from Above

Owing to its well-preserved architecture, Meili has over the past decade acquired acclaimed status, receiving multiple national and transnational cultural heritage protection merits, including being listed among Xi Jinping’s model ‘traditional villages’. Meili’s acclaimed traditional architecture can be enjoyed when approaching down the narrow mountain paths to the village, which offer a bird’s-eye view of thetraditional architecture of the village. Enveloped by lush evergreen forest and folded clastic mountains that crowd together, the compact rural enclave sits in the middle of a deep valley along the banks of a river. From above, the peaks of grey-tiled gabled roofs along the river lift to the skies, resembling a ruffled blanket of ocean waves. The architectural allure of Meili is enhanced by its covered ‘wind and rain bridges’ and a tall, pagoda-like drum tower, which is strategically located on a podium to orient the viewer’s gaze. Marvelling at the symmetrical intactness of the village scene and the looming backdrop of mountains and rich forest, viewers cannot help but be taken in by Meili’s beauty.

From a distance, Meili appears undamaged and intact and imparts an atmosphere that planners and tourists call wanzheng (完整). The ‘integrity’ of the village is enhanced by the skill of the crafting of the village pathways, drum tower, wooden pile houses, barns, and covered wind and rain bridges—all of which are valued by preservationists, who refer to them as yuanshi (原始), which is literally translatable as ‘original’ or ‘historically primitive’, or more generally, ‘authentic’ when applied in global heritage discourse. Similar to the more familiar term ‘premodern’ (原生态, yuanshengtai), yuanshi has become a popular phrase to epitomise the historical features of Chinese village architecture, including its material parts. Yuanshi has especially gained traction since the Chinese traditional villages protection model was first declared in 2012, when the soon-to-be President Xi Jinping made frequent references to protecting the ‘authentic style’ (原始风貌) of nominated sites as representations of China’s vernacular architecture (Li 2016).

‘Integrity’ and ‘authenticity’ are key criteria used to evaluate potential sites for nomination under the esteemed UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Because of this, celebrating localities for their historical integrity has become common practice among Chinese cultural heritage experts and decision-makers. Plans, protocols, and charters manage how preservation is practised, how space is governed, and how local people access space. Like the issue of integrity, President Xi’s focus on authenticity resonates with wider heritage discourse and international conventions. As historian and heritage critic David Lowenthal (1985) reminds us, within the realms of heritage protocols, the appraisal of innate heritage value is embedded in material forms and their properties. This becomes considerably more complicated in practice because ‘authenticity’ is rarely manifest in a single entity. In Meili, as in China more generally, the value of authenticity lies in rebuilding tradition—in the rural aesthetics of material forms and their natural surrounds, such as the scenic panorama of Meili when viewed from above.

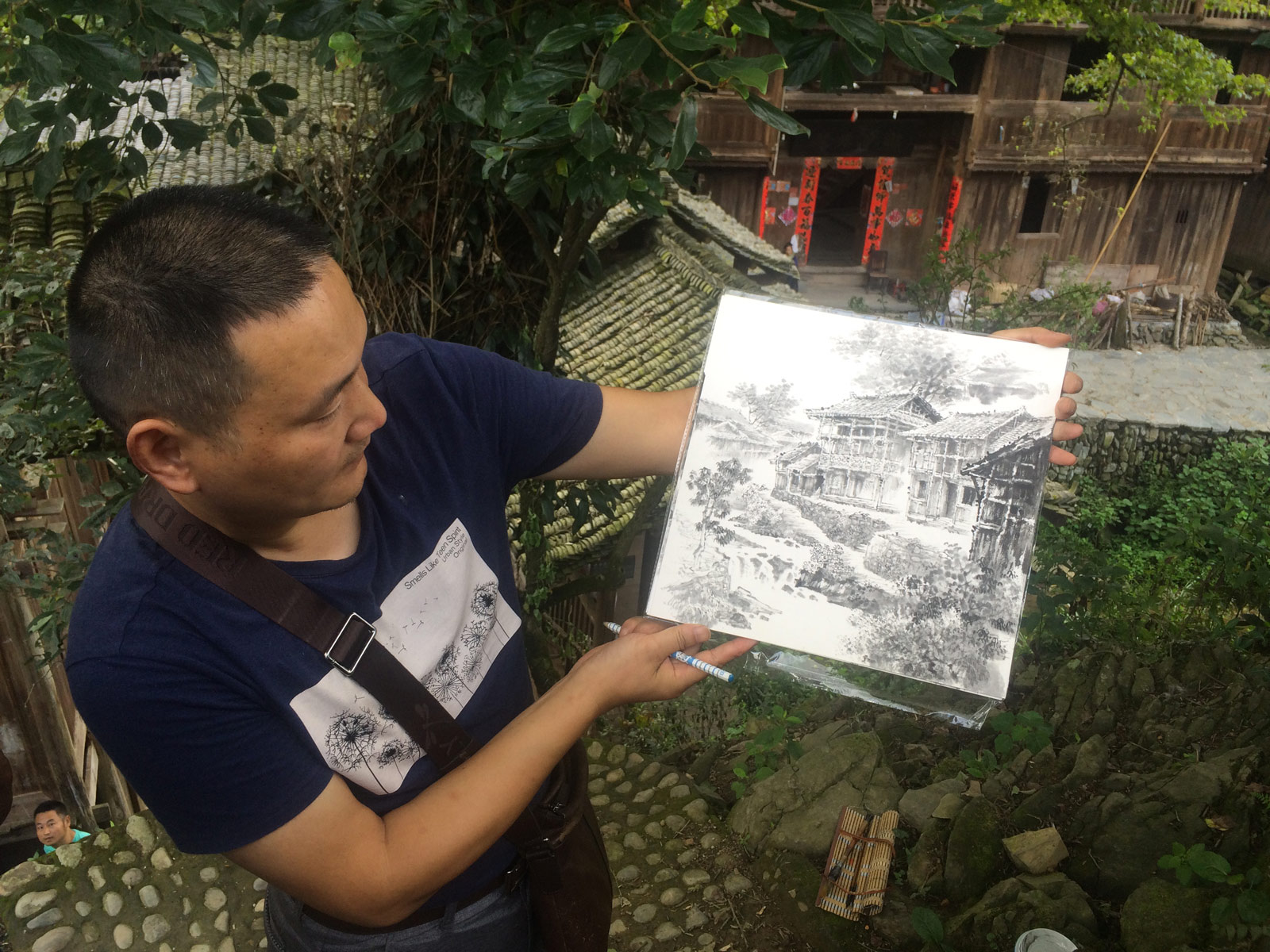

Source: Suvi Rautio.

Rebuilding Tradition in Wooden Homes

When I first arrived in Meili in 2014 and discussed the heritage scheme with local people across different age groups, they rarely had positive opinions. Many residents expressed embarrassment, humiliation, and low self-esteem when referring to the features that heritage discourse saw as providing the village’s charm. They saw the sea of wooden houses as a burden and a handicap to their everyday lives, while getting away from them was deemed an impossibility. Even before I entered a Meili resident’s wooden home, I would hear the humiliation in people’s voices as they informed me: ‘I am sorry, we are poor.’

With preservation measures in place to maintain the integrity of their homes, Meili households are prohibited from altering the wooden exteriors. Key actors working on the preservation scheme reiterated time and again that brick contrasted with the traditional timber and its use should therefore be prohibited because it interfered with the national preservation guidelines.

In questioning the importance of the materiality of their wooden homes, many villagers whom I came to know directed their criticism to the conflict of values between themselves and the heritage protocols. More implicitly, their criticisms echoed their frustration with the impositions of living in a heritage site that restricted them from obtaining modernity. This also echoed a broader critique of the dominant preservation ideology that prioritises the exterior form and substance of materiality and often overlooks the more intimate social, economic, historical, cultural, and political conditions that local people associate with that materiality.

Criticisms of heritage schemes stem from the scepticism and scorn many people in Meili feel towards the heritage practitioners and government officials driving these policies, suggesting that they begrudge these outsiders making decisions about authenticity on their behalf. Many locals are aware of the double standards of the project and in particular how practitioners working within the scheme find ways to navigate around heritage restrictions to craft their own impression of authenticity, or yuanshi. It is not uncommon for government officials and heritage practitioners to seek to maintain yuanshi through merely beautifying the village’s exterior. In Meili and beyond, villages often ‘get dressed and put on a hat’ (穿衣戴帽) as part of the ‘face projects’ (面子工程) of development initiatives undertaken by local officials to please higher-level government officers and elites, especially their colleagues and superiors in the CCP (Chio 2014).

One common method of ‘dressing’ is covering brick and concrete exteriors with timber. Seen from afar, the timber appears to show the integrity of the place and therefore conveys the look of a Chinese traditional village. This is but one example of how powerful outsiders well-versed in both national and international heritage guidelines craft preservation measures to their own benefit without breaking the material integrity of the village. In many other instances, these opportunities can give rise to compromise or conflict (Rautio 2021, forthcoming) when values attached to tradition are continuously redefined, embraced, rejected, or transformed.

Beyond the desires of the inhabitants of Meili, villages continue to be dressed and staged as loci of traditional cultural identity where carefully selected items of ethnic life are compiled, packaged, and displayed as aesthetic objects. The aesthetics that uphold tradition, like Meili’s integrity seen from above, are reproduced in the eyes of the beholder through a painting, photograph, or written poetry, to evoke a memory of a familiar place with no definite attachment to a fixed location. The constructed notion that the countryside represents tradition and retains an unchanging, timeless identity is a familiar point of attraction for tourists; as I heard one tourist declare on her arrival in Meili: ‘Being here feels like I have returned to my childhood!’ Meili thus becomes portable whereby the metaphorical and symbolic meanings carried by material forms can be infinitely imitated to provide a subjective experience for the viewer.

Tradition Serves Modernity

Since the founding of the CCP, ethnicity and multiculturalism have served a larger political agenda. Under Xi Jinping’s rule, ethnic minorities are laden with universalising heritage concepts and protocols that impose restrictions on their living conditions. Meili is just one example of the many ethnic minority villages in southwestern China that serve Xi’s narrative of tradition. Recast into a medium for discussing and lamenting traditions that are considered lost or vanishing, Meili is celebrated for the ethnic aesthetics of its vernacular architecture that is yet to be engulfed by urbanisation. The deployment of villages to invoke nostalgia for tradition, whether invented or genuine, is not unique to President Xi’s strategies for China’s marginalised ethnic places, but is also integral to the wider project of modernity (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983). Seeing the countryside and the ethnic as places and objects of nostalgic desire is a recurring ideal of modernity shared widely among the public in the European context, particularly since the Enlightenment. As a result of modernity, the dichotomy between the imagined rural identity—which appears as ‘communal’, ‘traditional’, and ‘serene’—and the ‘complex’, ‘heterogeneous’, and ‘diverse’ urban society has become a normative way of seeing the world. This dichotomy heightens the urban–rural divide, which in the Chinese context highlights the ironies of Xi Jinping’s urban integration policy: in its efforts to close the urban–rural gap, it is promulgating and reinforcing the conceptual divisions between the rural and the urban, tradition and modernity, and ethnic minorities and the Han majority.

As the Chinese State endeavours to portray the country’s multiculturalism in a positive light, it is inevitably solidifying ethnic minorities into categories that are perceived not relationally but through difference and ‘othering’. The representations of tradition that are imposed on ethnic minority villages like Meili and their inhabitants make them susceptible to outsiders envisioning rural life through rose-tinted glasses. Depictions that transform the quotidian into a sublime ideal inevitably gloss over the harsher realities of agrarian decline, underdevelopment, and the socioeconomic pressures that Meili residents—and a vast portion of China’s ethnic rural population—continue to face daily. Whether key actors working in the heritage industry will recognise the systemic limitations that rural residents face—and what they will do if they examine it—will determine whether Xi Jinping’s traditional villages continue to be inhabited by local people in another 20 years. If the heritage industry and, by extension, the Chinese State were to start integrating and problematising categories of ‘the other’ through relational rather than binary terms, the ethnic minorities living in heritage sites might finally start to see the promises of the CCP fulfilled as it enters a ‘new era’ of rural revitalisation and modernisation.

References