Oil and Water

Most Han in Xinjiang, Western China, have settled—or been settled by state decree—in the region since the Chinese Communist Party won the Civil War and took control of China in 1949. Since that time, the proportion of Han in the population has risen from 4 percent to at least 42 percent, and is now roughly equal to the other major population group in Xinjiang, Turkic Muslim Uyghurs. In my view, the massive project of cultural, economic, physical, and personal transformation that these migrants are involved in is rightly described as a ‘colonial endeavour.’

Since I first lived in Xinjiang for eight months in 2001-2002, I have been asking myself: ‘What is it like to be a Han person living in Xinjiang?’ I asked myself this question because I felt that it was not the same as being a Han person who lives in the core area of China. Perhaps the question came to me because, as an Australian-born child of European parents, I felt some sort of affinity with these settlers on the edge of their empire. Xinjiang was both alien and strangely familiar to me.

I returned to Xinjiang from July 2007 until February 2010 to conduct research on the experiences of Han settlers, centering my project on the oil city of Korla. The resultant book was published in June 2016 by the University of Chicago Press. The following gallery contains some highlights from an exhibition held at the Australian National University in early July.

Time

On July 5, 2009, Urumchi streets were witness to some of the worst inter-ethnic communal violence to hit Xinjiang since 1949. Angry and frustrated Uyghurs rioted, burned buildings and vehicles, and randomly beat any Han person unlucky enough to be in the path of the mob. Thousands of Han retaliated two days later, destroying Uyghur property and beating, often to death, any Uyghur witless enough to be present on the deliberately lawless streets.

A massive crackdown from the embarrassed and embattled Xinjiang authorities was imminent, violence past and violence-to-be hung heavily in the thick summer air, and fear and loathing was visible on the eerily quiet streets of Xinjiang’s cities. The only thing in Xinjiang that was not at least semi-paralysed was rumour, which spread like wildfire.

July 2009 to February 2010, in particular, was a crucible of politicized storytelling, fired by heightened emotions and unconstrained by the mannered niceties of peacetime. A certain kind of talk became briefly allowable as the assumptions of settler loyalty to Xinjiang and the precepts of Han occupation of the region lost their lock-hold over public discourse. The uncertain months following July 5, 2009, can be seen as a ‘decisive moment’ in Xinjiang’s recent history.

Morning, July 10, Friday, 2009. The supermarkets in Korla open for the first time since the Uyghur riots on July 5-6, then Han retribution riots on July 7. Despite repeated govt warnings to avoid crowded public places, all these people seem to want (aside from food supplies) is the comforting, familiar feeling of a supermarket crush.

Migration

Migration and colonial settlement are core elements of the experience of being Han in Xinjiang. Most Han in Korla are migrants within a generation or two, and have come to the region in a series of waves since 1949. The first major wave of Han in-migration to Xinjiang began in the 1950s; it was state-sponsored and directed towards a quasi-military agricultural colony called the bingtuan. The second major wave began in the early 1990s and is ongoing; it is economically-motivated and self-sponsored migration, but shaped and strongly encouraged by state actors.

The very act of migration into the ‘behindness’ that is Xinjiang infects the Han migrant with behindness, although at the very same time the movement often helps to raise their relative social status. Military officers and bureaucratic cadres posted to Xinjiang during the early Mao era (1950s) were typically promoted one level; self-sponsored farmer-settlers today are often granted land packages that provide an income far in excess of what they could earn in rural eastern China.

Civilians and bureaucrats are the front-line soldiers of the colonial endeavour, yet by becoming ‘Xinjiang people’—settlers, not just sojourners—they distance themselves from the cultural core and become themselves subject to this civilising project.

Mao-era Settlers

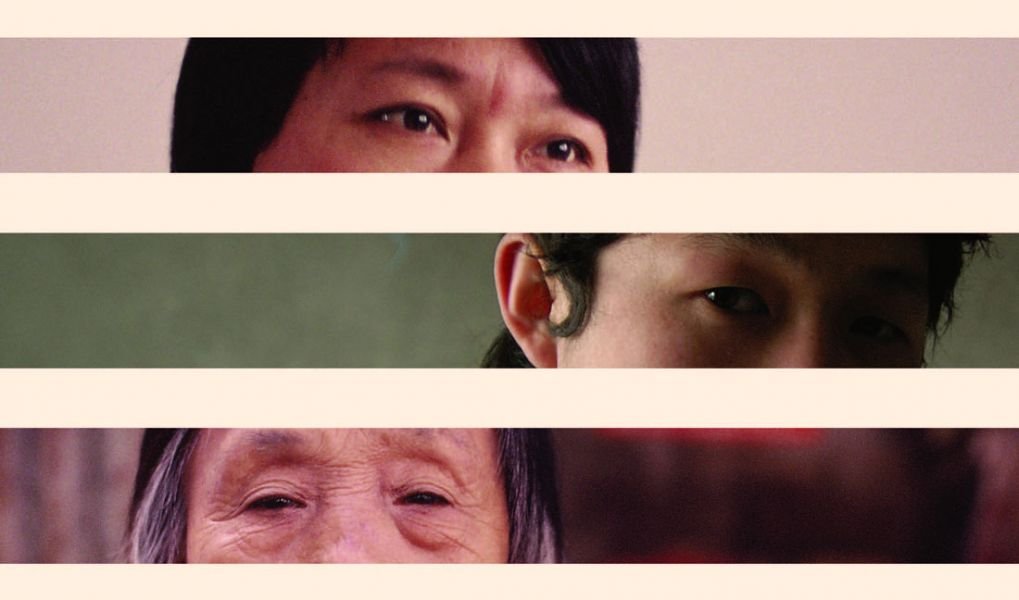

Dr Pei in the back room of his acupuncture and massage clinic, early August 2009. We were having a robust argument about domestic and political violence. Like many Chinese, Dr Pei was offended and angry that the Melbourne International Film Festival was showing a film about exiled Uyghur businesswoman Rebiya Kadeer, and that Australian authorities refused Chinese demands to drop the film from the festival program and deny Kadeer a visa. The Chinese government blamed Kadeer for instigating the July 5, 2009, riot, and very few in Han people had any cause not to believe that the riots were premeditated and that Kadeeer was the mastermind. Dr Pei wrung out his towel over and over, occasionally clenching his fist, and insisting that it was absolutely right to govern Uyghurs and women with violence or the threat of violence.

Dr Pei in the back room of his acupuncture and massage clinic, early August 2009. We were having a robust argument about domestic and political violence. Like many Chinese, Dr Pei was offended and angry that the Melbourne International Film Festival was showing a film about exiled Uyghur businesswoman Rebiya Kadeer, and that Australian authorities refused Chinese demands to drop the film from the festival program and deny Kadeer a visa. The Chinese government blamed Kadeer for instigating the July 5, 2009, riot, and very few in Han people had any cause not to believe that the riots were premeditated and that Kadeeer was the mastermind. Dr Pei wrung out his towel over and over, occasionally clenching his fist, and insisting that it was absolutely right to govern Uyghurs and women with violence or the threat of violence.

Pei Jianjiang (centre), with his two best friends from the transport company school. Mid-1970s.

Pei Jianjiang (centre), with his two best friends from the transport company school. Mid-1970s.

Pei Jianjiang (left), posing in a local photographic studio with the same two best friends, early 1980s. Soon after this photograph was taken, Pei began studying Traditional Chinese Medicine and martial arts.

Pei Jianjiang (left), posing in a local photographic studio with the same two best friends, early 1980s. Soon after this photograph was taken, Pei began studying Traditional Chinese Medicine and martial arts.

Ms Gu at the market garden that she runs with her husband. Ms Gu was laid off without a pension from her job as a kindergarten teacher at the ‘Third Front’ factory where her husband also worked for his whole life. The Third Front was an industrial policy (1964–1980) that relocated urban factories deep inland, supposedly to make them harder to bomb in the event of war. Gu and her husband were relocated to a remote valley North of Korla from where they lived in eastern China. In 2008, Gu was knocked off her bicycle by a passing motorcyclist; she sustained head injuries and suffered memory loss and mild brain damage. The effects of the accident put a strain on her relationship with her husband.

Ms Gu at the factory in the mountains, 1979.

Ms Gu at the factory in the mountains, 1979.

With husband and son, circa 2005.

With husband and son, circa 2005.

Mr Jia in his oil company LandCruiser in January 2010, looking out at the bingtuan high school that he graduated from in the early 1980s. At that time, bingtuan childrens’ greatest wish was to get into university–to shake off the bingtuan, because life on the bingtuan was very hard. At the same time, [non-bingtuan] people looked down on you and discriminated against you. So we studied hard–it was the only way out.

Mr Jia in his oil company LandCruiser in January 2010, looking out at the bingtuan high school that he graduated from in the early 1980s. At that time, bingtuan childrens’ greatest wish was to get into university–to shake off the bingtuan, because life on the bingtuan was very hard. At the same time, [non-bingtuan] people looked down on you and discriminated against you. So we studied hard–it was the only way out.

Mr Jia’s parents after arrival in Xinjiang, his father to take up a Company Commander position in the bingtuan, 1963. The bingtuan was set up as a military-agricultural colony in the early 1950s. Demobilised soldiers of both the Communists and their civil war enemies, the Nationalists, settled marginal arid lands, building extensive irrigation networks with hand tools and sheer force of numbers.

Mr Jia, aged 4, and his younger sister. He holds Mao’s ‘Little Red Book.’ It is 1969, a few years into the Cultural Revolution. The original was hand coloured by the studio.

Teachers awaiting a negotiation

Teachers awaiting a negotiation

It is Friday morning and some teachers are sitting in the often-absent principal’s office. They have just heard that their working conditions—hours, shifts, responsibilities, calculation of salary, etc—have once again been changed by their boss, the investor. One month they may have to work or be on-call at the small private boarding school all day every second day; the next month it is back to 12 hours a day, six days a week. They don’t like it, but teachers are common and many new ones are produced every year. These old teachers have little chance of permanent employment in a government school—if there was, they wouldn’t be here. They wait, and prepare themselves for yet another assymetrical negotiation.

Recent Settlers

p

Exploited tenant farmers on the bingtuan.

Exploited tenant farmers on the bingtuan.

Another exploited tenant farmer on the bingtuan.

The bingtuan began as a system of military-agricultural colonies, and was the main force behind Han in-migration to and cultural transformation in Xinjiang until at least the end of the Mao era. Today, the bingtuan is almost entirely civilian, but it is still seen by the central government as playing an important role in maintaining social and political stability in Xinjiang—largely because the bingtuan‘s 94 percent Han population occupies key peri-urban, rural and border regions. Moreover, the legal parameters governing this settler population remain different to those that govern non-bingtuan populations throughout the rest of rural China, including Xinjiang. These differential modes of governance result in a significant socio-economic and politico-legal divide between the bingtuan population (especially the newcomers) and the non-bingtuan population.

Their village in inland China was hit by a ‘natural disaster,’ so they opted to come to Xinjiang to start a new life. The conditions of their employment on the bingtuan as told to them before they came were apparently vastly different to the reality of how they are treated.

‘What we have is not even enough to support a family and send a kid to school’

They were promised 600 yuan per month as a minimum, whether they worked or not, but this has not been paid. Instead, they get 15 yuan per day, but there is always work arranged for them by the bingtuan authorities, so ‘off days’ do not really exist. Their house was apparently to be given to them, but after five years they are expected to pay ‘over ten thousand yuan’ and if they don’t pay they will be taxed five years of rent for their house. The house is bare, clammy, unheated, unpainted, and small to boot. The man told me that the table and wardrobe—both made from cheap plywood and not in at all good condition—cost 3000 RMB of their pay, and was a mandatory purchase. In this way, the bingtuan authorities justify holding back their pay. They have 6.5 acres and have to invest 10 000 RMB in agricultural inputs each year. The bad land that they work is more costly than that which earlier arrivals work because the tax price is fixed at the time of beginning the land contract with the bingtuan. The disparity between their income and their needs for investment means that they owe money to creditors at their old home in Henan.

Their household registration, which gives them access to basic health care and allows their child to attend school has been transferred to the village in Xinjiang where they now live. If they went back to their old home, they would effectively be ‘non-citizens,’ because they would not have these rights. Despite this, two-thirds of the people they originally came with have fled the bingtuan.

Train series. Migrant track workers returning home after a day’s work. North of Korla, October 2009.

Train series. Migrant track workers returning home after a day’s work. North of Korla, October 2009.

Han on the squatter-periphery of Korla, July 2009

Han on the squatter-periphery of Korla, July 2009

A due-for-demolition corner of old Korla, May 2008.

Empire

Water and oil are the liquid foundations of empires past and empires present. Karl Wittfogel famously coined the term ‘hydraulic empires’ in reference to the feudal formations in which the centre commanded the coercive power to mobilize the population, through corvée or slave labour, to build extensive networks of transportation canals and irrigation channels. Control over water, in a rather different sense, was also the basis of expansionist European colonial empires from the Spanish and Portuguese to the British. These empires relied on their naval prowess—exporting their early modern technologies of power (bureaucracy, culture and gunpowder-based armaments) into a spatial context where these technologies conferred an insuperable advantage over the ‘natives.’ In Xinjiang, the bingtuan established the irrigated basis on which extensive Han settlement beyond the oases could be sustained—thus transforming, throughout most of the region, the frontier of control into a frontier of settlement.

Water remains important, but oil now flows through the channels of the imperial landscape. Many wars and invasive manoeuvres of the recent past have been motivated by the desire for oil. Oil also fuels and lubricates the global economy, and supports and maintains the global status quo. Oil pipelines trace the linkages between political blocs, simultaneously blurring and affirming their boundaries and loyalties. Xinjiang is both an oil and gas-producing base, and an essential transit point for hydrocarbons extracted in Central Asia and consumed in China’s eastern metropolises. Despite being a domestic company, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), is increasingly involved in offshore investment and oilfield development, as well as being the majority player within the PRC. CNPC is the Tarim Oilfield Company’s parent. The trope of ‘oil and water’ thus references the liquids that motivate and enable Han activities in Xinjiang, the oil company and the bingtuan (as the formal institutions most closely associated with these respective liquids) and, more generally, the resources that have played and are playing the key roles in the expansion and maintenance of imperial formations. Last but certainly not least, ‘oil and water’ metaphorically expresses the diverse experiences of Han people in Xinjiang.

Mausoleum in a Mongol Autonomous County.

Mausoleum in a Mongol Autonomous County.

Apartment buildings in Korla’s New City District.

Apartment buildings in Korla’s New City District.

Abandoned cinema in former ‘Third Front’ factory south of Korla.

Abandoned cinema in former ‘Third Front’ factory south of Korla.