Risk: The Hidden Power of Art Creation

Risk calls forth the possibility of danger and challenge in the regime of art. It is an approach that artists draw upon to create new meanings and produce unexpected results in a world that is predictable. By stepping out of convention, the artist knowingly enters, struggles, and perseveres in difficult conditions, either resulting in a previously unimagined achievement or an expenditure that ends in complete failure.

Due to the elements of unpredictability and uncontrollability, risk is capable of keeping the audience in suspense and aroused expectation. For this reason, it is the perfect artistic weapon to arrest the soul’s attention. Risk offers different possibilities in art. Various elements can produce risk or achieve similar effects, such as random and contingent encounters and occasions. For performance art, risk is always the most interesting part. The indeterminacy of the event produces unexpected results and makes all performance art contingent on the singularity of the moment. Contingency offers art new possibilities, pathways, and unforeseen outcomes.

How Much Can a Body Endure?

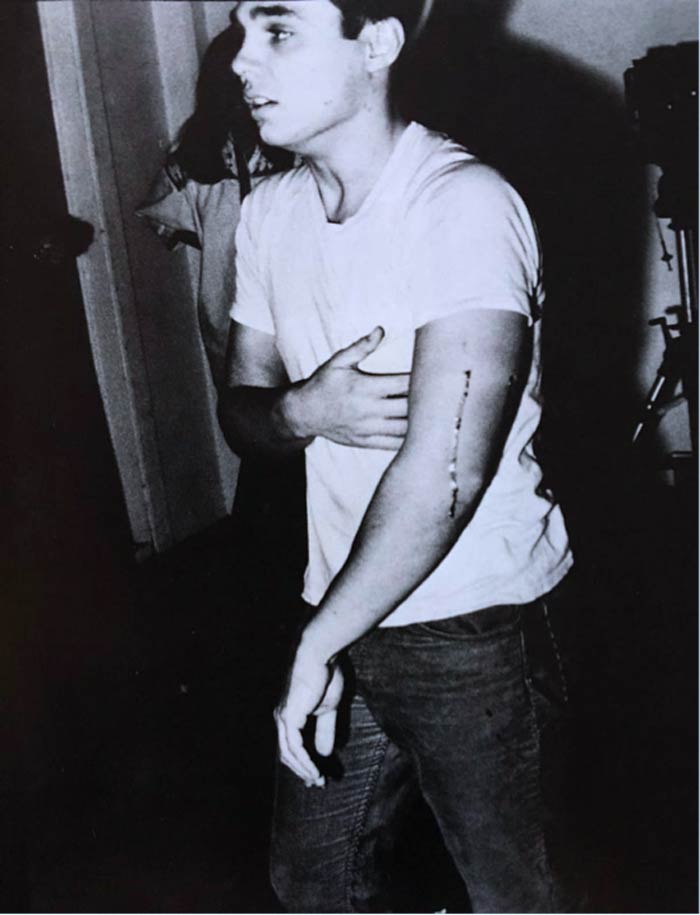

In the history of performance art, there are several artists and works whose legacies are profound. In California, American artist Chris Burden (1946–2015) made a name for himself by adopting an extreme method which sent intense reverberations throughout the art world. He performed several dangerous works of art, such as Shoot (1971), when he asked an assistant to shoot his left arm with a .22-calibre rifle from a distance of about 16 feet, and Trans-Fixed (1974), when he was crucified on the top of a Volkswagen Beetle with nails hammered into both of his hands.

Yugoslavia-born performance artist Marina Abramović (1946–present) has been described as the ‘grandmother of performance art’. She often puts herself in perilous situations and takes risks in her performances. In Rest Energy (1980), she and her then partner Ulay (1943–2020) held an arrow on a taut bow between their bodies aimed directly at her heart for four minutes and ten seconds. In Lips of Thomas (1975), she used a razorblade to carve a five-pointed star on her belly, allowing blood to flow from the cuts. Perhaps most controversially, in Rhythm 0 (1974) she offered 72 objects to the audience to use on her in any manner they desired, while she just stood there motionless. The objects included a rope, knife, prickly rose, bullet, and gun. This performance pushed risk and suspense to its peak. The constant presence of risk in Marina Abramović’s artworks pushes them to the extreme limit of art, and bestows their power and significance, making them unforgettable.

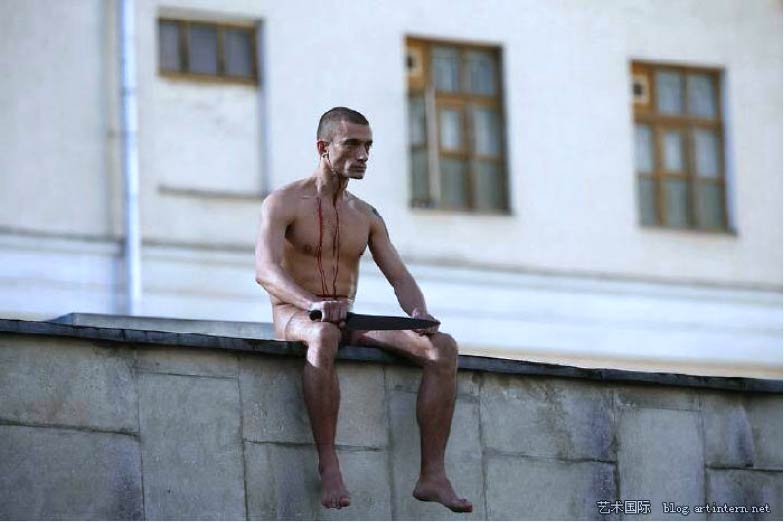

Extreme uses and explorations of the limits of the body have also been used as medium of political expression (Bargu 2018). In a piece titled Segregation protesting against the political abuse of psychiatry in Russia, Russian performance artist Petr Pavlensky (1984–present) cut off his right earlobe with a chef’s knife while sitting naked on the enclosure wall of the infamous Serbsky medical centre on 19 October 2014. In Stitch (2012), he sewed his mouth shut to protest the silencing of contemporary artists, specifically in response to the incarceration of members of the Russian punk collective Pussy Riot. For his performance Fixation (2013), Pavlensky nailed his scrotum to the pavement of the Red Square in front of Lenin’s Mausoleum to embody the ‘apathy, political indifference, and fatalism of Russian society’. In another work from 2013 titled Carcass, he rolled his naked body in a multilayered cocoon of barbed wire symbolically placed in front of the Legislative Assembly of Saint Petersburg. Each of his actions ended with arrests. The artist unsparingly subjects his body to pain to protest the status quo in Russia. By using the method of risk, his art conveys a formidable power.

Blood on the Wall

The symbolism of blood, what Gil Andijar calls ‘our political hematology’, evokes and connects the violence of politics and art. Artists not only spill blood in their performances, but also use its red materiality as paint on a canvas or graffiti on a wall. In 1988, Istvan Kantor (1949–present), a performance master from Canada, violently splashed his own blood on the wall next to two Picasso paintings at MoMA—some drops of blood even flecked on the painting Girl With A Mirror. Since then, despite countless arrests and appearances in court, he has performed similar artistic performances all around the world. During the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney Museum in 2016, he conducted a ‘dialogue’ by painting a red X on the wall, signing ‘Monty Cantsin [one of his aliases] was here’ in black marker, and posing for a selfie in front of it.

Each of Kantor’s performances requires courage in the face of risk. He cannot anticipate what will happen, so he needs to prepare himself to confront every possibility. For his MoMA performance he was fined an exorbitant amount of money and only after several years of court battles was the fine reduced to 1,000 US dollars. Another fine for ‘attacking’ the Hamburger Bahnhof Contemporary Art Museum in Berlin was paid off by an art fan. Kantor’s risky actions have elicited several media reports, extensive discussion, and wide-ranging public attention. He became a star of sorts. Despite art museums around the world shutting the door in his face, he was awarded the Canadian Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.

The blood of artists can also protest the blood spilled by states. In 2012, Kantor created another blood work on Ai Weiwei’s solo exhibition in an art museum located in Toronto, in order to pray for Ai’s safety (Ai was under surveillance at the time). In 2014, Kantor came to China and dripped his hot blood into two iconic rivers of China—the Yangtze River and Yellow River.

Performance and Prohibition in China

From its inception, this kind of ‘extreme’ performance art in China has been stigmatised, for the simple reason that Chinese people regard blood as a symbol of violence and nudity as pornographic. Actually, engaging in performance art in China has always been a risky endeavour because the government prohibits this kind of art from taking place. In the last few years, the preconceived stigma around performance art has lessened to a small degree, especially since the news of internationally successful performance artists has finally reached Chinese audiences. Now performance art has become fashionable. More and more younger people participate in it, but artworks that take genuine risks are still few and far between.

He Yunchang (1968–present) is widely reputed for subjecting his body to risk and self-mutilation, such as surgically removing one of his ribs. In one of his early works in the 1980s, Explosion (爆破), he risked his life for his art. The artist detonated explosive devices separated from his body only by fine writing paper used for traditional Chinese painting (宣纸) and a single wall. In One-metre Democracy (一米民主, 2010), without anaesthesia and aided by a doctor, he cut a meter-long and 0.5–1-centimetre-deep gash from his collarbone to knee. This work not only put his own body in danger but was also a political risk considering that the message was that Chinese people are not allowed to discuss democracy. To commemorate the events of June Fourth, in 2015 He performed Snow in June (六月雪), in which he allowed a group of people to chafe his skin with sandpaper leaving a mass of abrasions all over his body, as if it were in bloom. He is an artist who is not afraid of pain, or at least is able to endure it.

Another Chinese artist, Yang Zhichao (1963–present) has created similar artworks. In Iron (烙, 2000), he had someone use a red-hot iron to brand his personal identification number on his shoulder. He also had grass planted on his back to reveal the porous boundary between bodies, nature, technology, society, and the state. In another work, in which he was assisted by Ai Weiwei, he implanted a secret object in the flesh of his thigh, which will be disclosed sometime in the future. The method of risk and endurance of pain by these Chinese artists is an attempt to use their own suffering to convey the suffering of the nation at this particular moment in history.

When something accidental happens during the process of creation, the artist is able to take advantage of the situation and adapt to the circumstances at hand to improve the artwork. This is also viewed as a kind of risk-taking. Take, for example, the latest work by the Chinese female artist Xiao Lu (1962–present) titled Polar (极地, 2016). When she was drilling into an ice wall with a knife, she accidentally cut open her hand. In her own words: ‘When I was changing hands with the knife, I cut myself and when I saw the blood, I wasn’t scared. I was excited. It was beautiful. It was a real experience’ (Murray 2018). As she switched to her other hand, she pressed her wounded palm on the ice wall to reduce the pain. The imprint of her bloody palm surprised her, so she continued to drill for another half hour, as the blood from her wound congealed in the ice. Originally a rather banal performance took on a new and deeper meaning from the unanticipated effect of her own blood on the ice. As a result, the performance has achieved a mythical status.

Among successful contemporary Chinese artists, those like Ai Weiwei (1957–present) and Li Zhanyang (1969–present) know how to wield the magical weapon of risk to gain acclaim and influence. Ai Weiwei, a household name recognised around the world, is an example of someone whose experiences, and legends, are composed of a series of risks (Sorace 2014). Sculptor and installation artist Li Zhanyang has also taken risks in his criticisms of the frivolity of Chinese culture and fabrications of history. By using the method of public sculpture, Li Zhanyang reinterpreted the story ‘Wu Song Kills His Sister-in-law’ (武松杀嫂), from the classical Chinese novel The Water Margin, by subverting the popular image of Wu Song as lofty and upright, and a defender of traditional values against his adulterous sister in law Pan Jinlian. Instead, his sculpture depicts Wu Song in an exaggerated pornographic posture with a lewd expression. As a result, this work has stirred ongoing controversy, condemnation, and discussion throughout Chinese society.

Danger, Temptation, and Hope

In conclusion, risk expands art’s vitality and helps exploit the latent potential of artistic creation. It can be said that risk in art provides an opportunity and inclination toward the meeting point of an entirely new situation: a juncture for writing a new page in history. In China, the state could be considered the preeminent performance artist, making both the risks and rewards of artistic practices more exhilarating and dangerous.

Contemporary artists’ pursuit of the new compels them to take risks as frequently as possible (Groys 2014). Even some mature artists engage in risks to transform their old habits and break out of their encirclement in order to produce something new. Risk in art is about constructing an unanticipated future and implementing its power. Risk is danger, but it is also temptation, and even more so, hope.