A Letter from a Tehran Prison

My experiences in 2022 sound terrifying, but I know that they are only an insignificant footnote in this absurd year that we have all gone through together.

I was a knowledge and culture worker living in mainland China. In the past few years, because of my professional and social activities, I have been frequently harassed by the police. Before 2022, we could maintain a sort of balance. Sometimes they would question me, follow me, talk to my supervisors at work, or send people to surveil my public speeches and the activities I organised, but they left me space to participate in public life, including writing, speaking up on social media, blogging, and engaging in or organising offline activities.

But in 2022 there was no longer any rational logic to be found in their actions. Any action of mine could trigger the highest alert, reasons were no longer given, and there was no more room for reaching agreement. Between the spring and summer of 2022, when it was close to the anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre, as a long period of lockdown came to an end, I met with friends to dance in a public area and was put under house arrest for three days. Under political pressure, the media outlet for whom I had worked for six years illegally ended my contract and refused to pay me the full compensation I was due according to the labour laws. In early autumn, I left Beijing for Shanghai to join an art exhibition. I prepared fewer than 10 days’ worth of clothes, and never imagined that on this departure, I would not be able to return home again.

In October, on the eve of the Twentieth Party Congress, hundreds of thousands of Beijing residents found the Beijing Health Kit app pop-up had rendered them unable to return to Beijing. I was among them. After the opening of the exhibition, I was unable to return home and had no choice but to go to Guangzhou with other artist friends who participated in the art exhibition together. During this period, the zero-Covid policy continued to wreak havoc everywhere. Every day, social media was flooded with mourning. Xi Jinping’s break from tradition to maintain leadership for a third term and filling of the Politburo with a team composed entirely of his own people generated great despair. On the other hand, the brave, lone-wolf banner-hanging protest at the Sitong Bridge in Beijing produced undercurrents of protest sentiment. Overseas Chinese in the West posted ‘Overthrow Xi’ posters everywhere. Amid a suffocating and terrifying atmosphere of collective silence inside the country, young people began to act. The upsurge of protests in Iran at the same time gave China’s young people inspiration. In Guangzhou, we organised events sharing the art of the Iranian protests and making posters in solidarity with those facing the violence of the Iranian authorities. At the same time, we were secretly producing resistance artworks in relation to the Chinese context. Friends around me quietly took action.

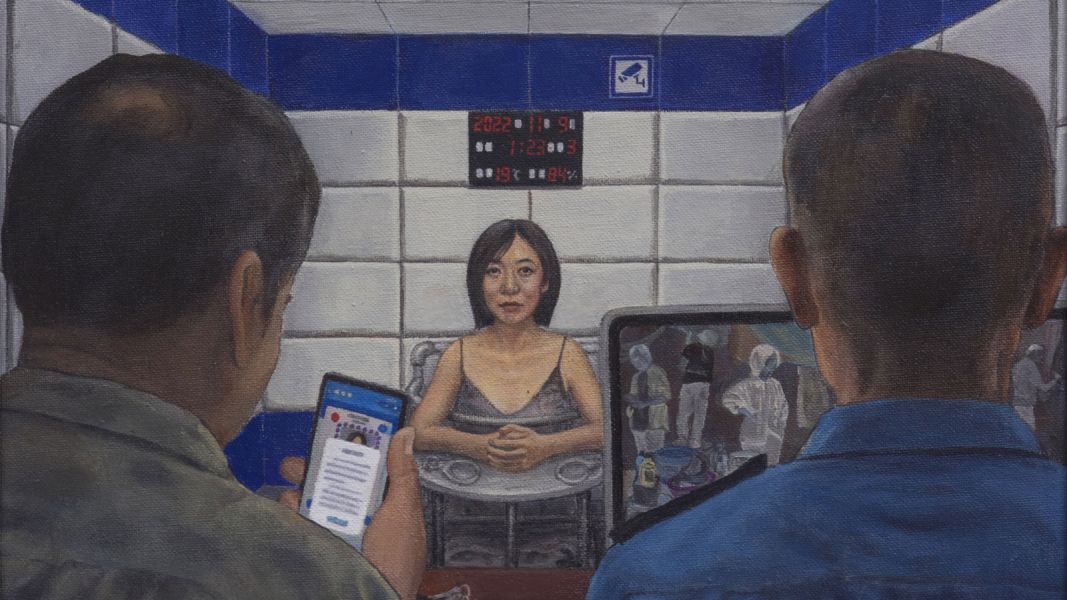

By the end of October, the pandemic situation in Guangzhou was out of control. I would wake every day and open my phone to private and group conversations filled with the rumours and counter-rumours about lockdown. Multiple times I tried to return to Beijing, without success. I was in a desperate situation, terrified of being trapped in lockdown again, until the Beijing Domestic Security Police crossed provincial borders to arrest me in Guangzhou on the suspicion that I had participated in the series of actions since the Sitong Bridge incident. On the day I was arrested, several people with Guangdong accents wearing white protective coveralls and pretending to be pandemic prevention health workers forced open our door and falsely accused us of harbouring someone who had come from a high-risk area. They requested we undergo antigen tests. When they had taken our IDs and read out my name, five police officers with Beijing accents charged in from behind the ‘health workers’ and took us all away. Ironically, because my Beijing Health Kit app still did not allow me to return to Beijing, they had no choice but to give up their original plan to bring me back to Beijing for questioning. Afraid of staying too long in pandemic-ridden Guangzhou and being unable to return themselves, they hurriedly finished the interrogation and rushed back to Beijing. Because the zero-Covid policy made it difficult for Guangzhou detention centres to accept new detainees, I was granted a temporary reprieve of 15 days of administrative detention for ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’. As soon as I was released, I rushed out of the lockdown area of Guangzhou at the very last minute and flew to an island in the south to lie low. I was asked to report my whereabouts to the Beijing Domestic Security Police, waiting for the investigation using the data they had copied from my devices. Less than two weeks later, the A4 Movement against censorship and pandemic lockdowns began. My friends in Beijing began one by one to disappear. At that moment, I decided to escape the country.

The fear of tyranny has kept my mouth shut this year, but I realised that being deprived of the right to speak causes more pain than all the other mistreatments. The intense, concurrently unfolding Iranian protests that I had been closely following became a way to transplant an imaginary framework, allowing me to tell the real story of what happened to us. The Chinese edition of the Artforum website published this story on the eve of the Lunar New Year. Other than the magazine editors and those who closely worked with me, only those who were featured in this first transmission of the story understood what it was really about. As the story was shared, people sighed at how similar Iran was to our country. Practically no-one realised that this was describing our own reality. Because of this, the article was not censored inside the Great Firewall.

The moment the story was completed and published, I still did not know which would come first—the next day or my arrest. As soon as I finished writing, I ignored the secret police’s orders to report my location, flew to Yunnan, and prepared to cross the land border to Laos. According to my lawyer’s instructions, I needed to prepare materials for an online support campaign in case of my arrest. As part of these materials, I decided to add footnotes to my disguised biographical story, ‘A Letter from a Tehran Prison’, to bring it back to its Chinese reality. The story ended with me being arrested again. If I could make it out of the country, that ending would continue to exist as pure fiction; if I was to be arrested at the border, it would become my testimony in court, along with the decoded footnotes.

On 24 January, I smoothly crossed the border and left China. I left in such a hurry that I did not have time to go home and pack my luggage, settle my cats, or tell my family what had happened.

10 February 2023 (Edited on 1 December 2023)

Mother,

It is my second day at the Qarchak Detention Centre. This winter is especially cold for Tehran. Thankfully, the prison up north in Evin is already overcrowded with political prisoners, so I’ve been dragged to this one in the south. Otherwise, I might be in an even worse situation! I’m still wearing the clothes that I wore when we said goodbye at the beginning of September. I left home then with only two sets of early autumn clothing; I would never have imagined that it would be so long before I could return, and especially not in this way. Have you watered my plants for me? Even in winter, ferns need a lot of moisture, and the alocasias need plenty of sun. Has my lemon tree borne any fruit?

I’m going to try to write this letter to you, even though I don’t know whether it will reach you in the end. I imagine it will most likely get thrown away, by them. Not because this letter would be any threat to them, but simply because of their habitual cruelty and coldness. Do you still remember Farah? She’s the girl I mentioned to you before, who was arrested because she was in Balochistan doing research. They accused her of endangering national security and she was sentenced to 15 years. She has been inside for four years now. The books we sent to her never reached her. And the novel that she wrote while in prison she sent to Ali, but it had been ripped apart so that only the table of contents was left. I saw Ali last month, after I was released from the first interrogation. He told me that Farah recently called him from prison. It was the first and only time he had heard from her this year. Her voice sounded as undefeated as ever. As we said goodbye, Ali swallowed the words at the tip of his tongue. He, I, and all our friends already know without saying that I am living on borrowed freedom—yet we are careful not to burst the bubble. ‘I’m sure that no matter what happens, you too will remain as undefeated as ever …’ As the words left his mouth, I could no longer hold back my tears and began to cry.

I think perhaps everyone will be disappointed in me. At the end of the day, maybe I’m only a weak, petty bourgeois intellectual. Ever since being stripped of the work I am passionate about, I have been practising the experience of loss all year. Every night I hold my two cats and quietly say goodbye. But I realise that there is so much that I am afraid to lose—even the several thousand books at home—so I will fall apart at the first blow. The morning I was arrested, I had just ordered a batch of secondhand records online. They probably arrived a while ago, no? I’m not sure when I’ll be able to listen to them now. I had even added a blender to my shopping cart that day—thinking I could make pomegranate juice for breakfast—but it was quite pricey, so I had hesitated and didn’t click through to make the payment. Can you believe it? In this one and a half days of being in prison, what torments me most are these shameful little bourgeois attachments. It’s as though the loss of everyday life itself is more painful than the loss of all that I have achieved and of the meaning I found in the work I loved.

Oh yes, Ma. All this time, I haven’t dared to tell you about losing my job. It was on the cusp between spring and summer. I was put under house arrest simply because my friends and I had gathered to dance on the street.[1] How terrified this regime is of any spirit of freedom! Afterwards, the secret police contacted the newspaper where I work—it was not the first time—and the editor and senior management were no longer willing to bear any of the risk I brought about. You know that I have always been willing to understand and empathise with cowardice and timidity. But the newspaper bet that I wouldn’t risk offending the authorities again by disclosing the reasons and circumstances for my leave (and, yes, they were right!), so they used the elephant in the room to refuse to comply with the labour law and pay full compensation. That kind of repeated haggling about pay, as if we were at a vegetable market, really makes them so despicable! What would you call them again? Those evil-enticing Jinns.

After being released from the first interrogation in November, I was plunged into an endless wait. The pending detention due to Covid measures had put my life under the Sword of Damocles. The secret police called irregularly to inquire after my whereabouts, warning me that wherever I went, any plans must be reported in advance. Lawyers and all my experienced friends just kept telling me to wait a little longer.

I deleted social media accounts, cleared files from my computer and mobile phone, withdrawing from public life, swallowing all the injustice, sinking into an abyss of silence. It was as though every second and every minute of my life were hanging in suspense. I knew that I was only waiting for the police to investigate me more thoroughly with the information they had copied, waiting for my freedom to be snatched away again.

During the day, I spent a great deal of time reading the prison notes from people who had been arrested over the past few years—mentally preparing myself. When I read that up to the very end of his time in prison, Amin refused to plead guilty, that he stammered out his final statement in the Tehran High Court, saying, ‘I am willing to sacrifice my freedom to defend everything that I have done’, I buried my face in bed and bawled, doubting whether I had it in me to handle all the difficulties I will encounter.[2] The nights were filled with nightmares about fleeing, arrest, and imprisonment. Sometimes the thunder and lightning from outside would enter my dream sequence of being taken into custody and interrogated, and I would be startled awake. But the sense of fear and despair in those dreams is always so similar that I never remember anything after waking up. The only dream that left a strong impression was of the most everyday of things: I dreamed about cooking for friends at home in Tehran. And the dream went on for so long that I remember every single step of preparing every single dish. When I imagine my friends’ ‘oohs’ and ‘ahs’ of delight on seeing my cooking, I feel happy. But the reality I wake to feels so much bleaker.

In my most desperate moment, I even took the initiative to contact one of the secret police and asked him whether he could take me into custody right away. He said: ‘Just wait for the updates.’ Every day I thought, if I had been immediately imprisoned that day, at least it could have aroused a wave of support and reignited the fervour of resistance—rather than being forgotten like this.

The pain had already started to fade. I signed a statement promising not to reveal any details of the interrogation. Every time the urge to write down those fragments of thought and feeling came, I realised again that nowhere would be safe enough to record them, and I let the thought go. My computer and phone no longer gave me any feeling of privacy. They had been tools of surveillance for the state for a long time, of course, but after being confiscated by the secret police for 30 hours, they had become as untouchable as some kind of virus (while the real virus around us no longer terrified anyone).

Memory becomes fractured. Those ‘404NotFound’ messages make you unable to remember what happened just the day before yesterday, much less the day before that. All our conversations become difficult and disconnected. Only when we activate auto-delete on messaging apps do we gain the slightest sense of safety, but often when I wake up and read replies from the other side, I can no longer remember what I said to which they are responding. I reluctantly watch as messages full of warmth disappear after 10 seconds, 30 seconds, or one hour. But there is no way they can stay for longer. I don’t dare take screenshots because anything can become evidence.

Yes, forgetting is an atrocity. It is the accomplice of tyranny. But living in this country, the reality even more difficult to avoid is that memory is a crime. It not only makes you suffer more and life harder to bear, it also can become evidence in the hands of the secret police at any time, throwing you into an unimaginable abyss.

***

Now I will finally tell you about the first, very elaborately executed arrest.[3]

On the most ordinary day in November, they used the tactics of major crime units to ‘entrap’ me, dispatching so many people who came all the way from Tehran to Sanandaj in layers of ambush and disguise.[4] This later became a way for them to humiliate me during the interrogation as they would denigrate my intelligence as no match for the nets they had laid. But the funny thing is that I had not even been hiding, it was simply an ordinary day and an ordinary gathering with friends. At the time, I was in the kitchen adding tomatoes and chickpeas to dizi. We had let our guard down under the Kurdish-language camouflage of a local Sanandaj informant disguised as a fellow traveller. They burst into Hedieh’s house, shouting: ‘Everyone on your knees!’ Adel knelt reflexively and was immediately pressed to the floor. The two young girls, Noor and Hedieh, stood to one side absolutely still, frozen in place. I instinctively began shouting in Kurdish and resisting, but then I heard the most violent language cut through me: Tehrani Persian.[5] The combined violence of divine right, of the state apparatus, of ethnic-majority chauvinism, and patriarchy—all elicited so clearly. ‘Don’t you recognise my accent, Mahsa? Aren’t you happy to meet someone from your hometown so far from home? This time we’ll take care of you for sure!’ These poisonous opening lines, full of provocation and oppression, reverberated in my mind long after the scene was over. Even though I was born in Tehran, as a Kurd, I will always be an outsider. Since a young age, I have always made a concerted effort to avoid being corrupted by Tehrani Persian. Realising in that moment that things were probably much more serious than I had imagined, I immediately quieted down.

They didn’t show their IDs. There was no official summons or arrest warrant—only handcuffs and that accent to make the threat clear. My friends and I were taken away, our mobile phones and computers confiscated, and Hedieh’s parents’ house was searched inside and out. I was stuffed into one car, and the others into a different car. It was dark and I couldn’t see anything clearly. I only remember that they stopped briefly at the nearby police station. You know that the government is on the verge of losing control in the Kurdish areas, so many police stations were already occupied with protesters and couldn’t be used for interrogation. The 480 kilometres to Tehran would have been too big a risk for our team, because as soon as night falls, many of the cities and towns along the way are like warzones. In the car, they incessantly berated me. It was because of me that they had to come so far on such a dangerous journey, and no-one knew whether they would be able to make it back safely to their cosy nest in Tehran.[6] They never forgot to add more venom to their admonishments: ‘Hedieh, Noor, and Adel have been taken away because of you, and they are going to resent you for it!’ (I knew they wouldn’t, of course.) In my anxiety, I lost all track of time, so I am not sure how long we drove, but, after a great deal of effort, they finally found one station in working order in the Kurdish area. I only remember that when we got there, it was already late at night.

By the time they finally brought me into the basement of that police station, the fear that I had barely suppressed with faith came crashing down on me, and the thought that justice was on my side completely dissipated. First, I saw an enormous cage. Inside were two filthy-looking men sleeping despite the bright incandescent light shining above them. Completely without dignity. There was a darker area further back with another cage, and when I arrived there was no-one else, but later, when I went to the toilet, I could see a few women being brought in one after another. There were interrogation rooms on every side and I was taken into one.

Most of the time was spent waiting, on edge. I’m so weak. Their questioning had barely begun and, without them having to use any ruthless tricks, I handed them the password for both my phone and my laptop. They would leave the room and come back again and again, in each instance bringing more ‘evidence’ that they had found on my phone or computer. I found out later that Noor had held on for six hours before giving up her passwords. Feelings of unease meant I constantly had to go to the toilet, but that was probably the most humiliating experience of the whole interrogation. The toilet was at the base of a stairwell in what was basically a hallway and there was only a symbolic partition about one-third the average person’s height to provide privacy. It was just tall enough that, when squatting, you were only barely hidden from sight, and every time I had to rack my brains to find the right position for bending over while holding on to my trousers so that the gaze of male police officers passing through the corridor would not reach me. A female police officer from Tehran was assigned to watch over me while I went to the toilet, but when she was not around, a male officer would take on her role. Once you are accused of a crime, it’s as though even not wanting an unknown male police officer to see your most intimate of actions is also an inappropriate request.

When the interrogators from Tehran were not around, there were always still a few vicious-looking middle-aged local cops posted in the middle of the basement, monitoring all the surrounding rooms. My frequent urination problem gave me the opportunity, however, to occasionally glimpse what was going on in this underground space outside my interrogation room. I inadvertently overheard a few relatively younger assistant interrogators in the corridor whispering in Kurdish, complaining about having to do overtime accompanying these fancy bigshots from Tehran, who were constantly on their backs: ‘Yeah, right, they’re from the capital, they don’t follow protocol one bit! They enter the room and don’t let suspects go by the timer. Because they’ve already decided to break the rules on interrogation time!’ I also heard outside my door the Tehrani cop who questioned me pressuring the local cop to delete all the records once my interrogation was finished, including all surveillance camera footage from inside the room. All this information made me go completely limp. Time seemed to drag interminably.

While passing other rooms, I tried to spy on what was going on with friends. Sobbing sounds streamed incessantly from Noor’s room. She’s too young and has never experienced this before, probably has not yet learned how to hide her frailty in the face of violence. The secret police officer in charge of questioning her was about her age and, as he faced her, his words oozed with flirtatious trickery. I heard him say in a greasy voice to a sobbing Noor: ‘I’ve never even been so gentle with my wife.’ Later, she told me that every time other, middle-aged officers from Tehran came into the interrogation room to intimidate her, he would immediately try to calm her down, coax her, and try to make her smile. The few experiences Noor has had with romance always involved men playing her. So, when a young man intensely paying attention to her in a confined space and for a long period listened to her and sat by her side while she cried, how could she not reveal her weakness? But this was probably all a trick especially designed to break her! As we sat together in the mediation room of the entrance hall to sign documents and carry out the remaining formalities when it was almost time for us to be released, I was shocked to discover that there was a strong sexual tension between the two of them. ‘Is your hair naturally this colour? It looks so nice!’ ‘When will you take me to dinner?’ ‘Your statement was so full of inconsistencies; don’t you know how much trouble I went through to help you fix it up?’ Every time he finished a sentence, Noor would lower her head with a shy expression. Through these intricate interrogation techniques, they seemed to be conducting an experiment on human nature—so shameless! It made me think of what Sepideh told us about her detention, in a closed-door gathering after she was released from custody. A female police officer would often come to her for heart-to-heart talks in that confined, windowless room, telling her that it was because she wasn’t pretty enough, had low self-esteem, and was naive that she was an easy target for the male revolutionary leaders in her university to coax into wrongdoing. And she was told that she wasn’t the only young, naive girl deceived by those male revolutionary leaders. In the long and lonely confinement, those ‘heart-to-heart’ moments were surprisingly warm for her—each time ending with her tears, to the point where she was on the verge of giving up her own beliefs and believing in the earnest words of the female police officer. When friends heard this in that gathering, Maryam almost spat on the ground and my hand tightened into a fist.

Oh, yeah, and late one night while most of the interrogators were either in meetings or napping, the police officer interrogating Noor came into my room during a break and pretended to make small talk. He was vividly recounting how he had been trailing me several months ago, when suddenly a rapist was brought into the basement. He immediately lost focus and, in an irritatingly flippant tone, said: ‘We’re in the Kurdistan now, go find some “whores” on the black market, why bother with rape!’ Yes, he used the word ‘whore’, the most filthy and humiliating language you can use on women. Can you believe that this came from the mouth of a defender of Sharia?

The treatment Hedieh was given was of another kind. ‘Your parents haven’t retired yet, right? Don’t you have a nine-year-old little sister?’ This was definitely the most despicable of this whole interrogation process. The threats to her family made Hedieh completely surrender, and the interrogation aimed at the same time to sap all her determination. The excessively long silences between each question during those 24 hours tortured her already exhausted body. Each time I went to the toilet and passed Hedieh’s interrogation room, she was motionless, holding on to both her legs and curled up on that cold, metal chair—a statue. Later she told us that she didn’t even go once to the toilet. We were allowed to see one another for the first time when it came time for the urine test, but there was someone with eyes on us the whole time, forbidding us to speak. Noor and I discreetly linked fingers but were immediately commanded to stop. When Hedieh came out of the toilet, the cup she carried was full of blood-red urine, startling the male police officer conducting the examination. The female officer next to him casually commented, ‘Got your period, eh?’ It was the first day of her menstrual cycle and who knows how she endured the rest of this torment.

The cop interrogating me was a high-ranking officer of the Tehrani secret police and the most experienced of them. As soon as he obtained the password for my phone and unlocked it, he flew into a rage and came into the room, asking why the audio recorder had been on the whole time. ‘You like to talk about rights with the police, don’t you?! When a cop speaks to you, you start recording, eh?! You think you know the law, right? But you need to be taught a lesson!’ During questioning, he would sometimes use his authority to beat me down. ‘What I hate the most is that you think police are all stupid fucks!’ It was as though every word I said was wrong, putting me in an ever deeper snake pit. At other times, he would use threats of punishment to scare me: ‘Repeat what you just said again! How many years do you want to be locked up?’ This went on to the point that, in the end, almost all my statements were his own utterances. At yet other times, he would suddenly become open-minded, expressing his understanding of those who try to protect freedom—and his sympathy with the plight of Iranian women. He urged me to believe that the authorities are not all the same. From his position of superior power though, he seemed to enjoy the process of breaking down my self-respect bit by bit, and the 24 hours were basically an entire minefield of gaslighting, to the point that when my will was at its weakest, I almost believed that he was doing this for my own good, that he was helping me to obtain clemency from the system.

When I was handed my final statement to look at, I noticed a procedural error at the very top of the transcript. The line saying ‘I need to contact my own lawyer’ had been automatically selected for me as ‘Not necessary’. The response to ‘I have already read the Interrogation Standards Manual’ had also been automatically selected as ‘Yes’. Even though 20 hours had passed, I didn’t know what this so-called ‘Interrogation Standards Manual’ was. When I questioned him about it, he replied apathetically, ‘These can be changed.’ Then he handed me a set of documents about interrogation standards. Noor and Hedieh had no experience dealing with such mechanisms of violence, so when I asked them about it later, neither had noticed these details, nor had they carefully looked at their statements before signing.

The most laughable thing was these cops’ arrogance and stupidity. The Balochi poem of resistance that my friend wrote was pinned on me, even when I clearly don’t understand Balochi! They can’t even tell the difference between Balochi and Kurdish, can you believe it?! They could have just looked it up on Google to tell the difference. The Kurdish policeman who was taking notes for the Tehran cop doing the interrogation looked embarrassed and I almost laughed out loud as I argued my case, Insha’Allah![7] He even asked me in a gossipy tone whether Mani, who speaks out for sexual minorities, has AIDS—just because he’s gay! But he saved his most vicious techniques for interrogating me about whether or not I’m a feminist. In the other rooms, the secret police also baited Noor, Hedieh, and Adel to point me out as a feminist. It’s as though compared with everything else, being a feminist would be the absolute worst crime of all! I felt confused. If he had asked me normally, I would have told him without a second thought that of course I’m a feminist. Then, when he pushed me to admit that all our work vilified the Supreme Leader, he didn’t even dare to say his name himself. What a joke!

We finally began to relax while going through the pre-release procedures—and the police officers did as well. Practically every Tehran officer came to brag about when they had been on my case, about where they had trailed or investigated me. Then, afraid that I would think myself too ‘important’, they would never forget to add: ‘You’ll never amount to anything! What a waste of our energy!’ The one who appeared to be the highest ranking of the Kurdish officers seemed to want to grab this last opportunity to show the cops from the capital his loyalty to the regime and he flaunted the dignified Persian education he’d had by lecturing us: ‘Do you understand Iran’s current status in the world? The United States and Israel are eyeing us like prey, our strategic friendship with Russia is unstable, and China and Saudi Arabia are flirting with one another. We are under attack from front and face—’ I quietly corrected his fired-up speech, inserting the correct aphorism, ‘Under attack from front and behind’, and my companions sitting beside me couldn’t help but giggle. One of the Tehran cops immediately came to his rescue: ‘You’ve gotten too comfortable standing up to the police, Mahsa!’ ‘This isn’t standing up to anything. I’m just a text-based worker, it’s an occupational habit,’ I whispered. The Kurdish officer finished his specially prepared tirade with embarrassment. By this time my companions were laughing more loudly, so, after 24 hours of humiliation, it felt like we were finally able to bounce one back.

The most interesting interlude came from Adel, the only male present at our gathering that day. He had managed to secretly clear his phone before it was confiscated, allowing him to remain completely undaunted during interrogation. But you know how his phone was snatched? In the chaos of being ambushed, he had been using Noor’s phone to film the scene of them storming in and, after he got down on his knees and the cops pushed him to the floor, they grabbed it from his hands. So, the police thought they had already taken all our phones but missed his. While he was waiting to enter the interrogation room, he stuck his hand in his trouser pockets and managed to send messages to friends telling them we had been arrested. But of all things, he sent a message to a group chat that I was also in and my phone was at that exact moment in the hands of an officer! So, they immediately went to him and confiscated it.

There aren’t many other light-hearted stories. The waiting time was far too long and, as I sat in the interrogation chair, my herniated disc flared up like a fire. It was honestly too difficult to bear. When I wasn’t going to the toilet, I would keep pacing back and forth across the room, mostly walking backwards with small steps to try to ease my back pain. I kept running into the table and chairs, attracting the rebuke of the most ferocious of all the basement-monitoring cops. That middle-aged police officer loudly threatened several times to chain me to the interrogation chair. By four in the morning, I didn’t have the strength to move anymore, so I lined up three wooden chairs in the room against the wall and lay down to rest. I’m not sure whether it was the blinding white lights or my incredible fear and feeling of helplessness, but sleep did not come to me. I held on tightly to the cardigan I had grabbed from Hedieh’s house before we were taken away—the only bit of warmth to calm me in that icy space. I tried with all my might to imagine the days Farah and other imprisoned comrades must be experiencing. I pictured Vida, Sepideh, and a few other friends: even if they did get out, it would only be to enter an even larger prison, with new names and new identities given to them by the government, where they would be hermetically sealed and under surveillance to suffer false lives. The images from Sepideh’s protest actions had appeared in numerous reports and, after she was released from jail, when at gatherings or public events where unfamiliar people were present, she often spoke directly without regard for the risks to the organisers and hosts. She wanted to be recognised by others. It took me a long time to understand that she just desperately longed to reclaim her own name. If I imagine all this might be a template for my own future, I fall apart immediately. Some moments I think, if I don’t have the courage to live that kind of life, would I have the courage to end my own life? But then I’ll think of Maryam, Reza, and the other comrades on the outside who are surely trying to find a way to get us out, and just as quickly I’ll erase the thought. I must rely on my belief in not being forgotten, force my will together, and try not to fall apart.

An Azerbaijani-looking officer who never said a word sat on guard in the middle of the basement and at one point he brought another wooden chair into my room and gently placed it under my dangling calves. He thought I was asleep. In the total span of 30 hours of interrogation, it was the only time a tear fell from my eyes.

Mother, have you seen the film The Lives of Others about the East German Stasi? When I saw it a few years ago, I thought it was a good film, but watching it again after these years of living under increasingly close surveillance, it struck more of an emotional chord. The scene with the Sonata for a Good Man is so moving. When the secret police wiretap the house of the East German intellectuals, the Stasi are so moved by their music, emotions, and ideas that they tacitly help them to escape punishment. Today’s surveillance is completely driven by big data and algorithms, so even thoughts, emotions, and artistic creation become mechanical, fragmented ‘keywords’ to alert the authorities, closing the last fissures through which humanity could be awakened. I cannot help but wonder whether, if there were people patiently watching us as well, there would be at least one or two of them, these henchmen of the state, who could be moved by our work, by our feelings and thinking, too? Would they be moved to stand by our side?

It wasn’t until the very end when it was confirmed we would be able to leave that they finally brought out the warrant that should have been presented at the time of arrest. They asked us to sign and backdate a document that listed ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’ as the reason for detention.[8] They only let us glance at it, saying that it was because the Kurdish area is unstable that the detention centre was temporarily unable to carry out our detention, so we didn’t need to take away the document. As we exited the police station, I saw the Azerbaijani-looking officer had just finished his shift and was walking in front of me with a few other guards. I quickly walked up to his side and quietly said, ‘Thank you.’

***

These past two years, everyone around me is discussing whether to leave this country. I remember one year ago Reza and I went deep into discussion about his experiences after being arrested during the 2009 Green Movement. Despite watching so many people leave the country, he had steadfastly decided to stay. ‘History has not come to an end; we still live within it. We have responsibility!’ He said we have to stay, to take back our country. Pointing out all those who’ve left, he said they end up with even less of a voice. In this land, their mouths are muffled, but after they leave and can raise their voices, how many people out there care about what they have to say? Their voices, after all, only belong to this land. And, in the end, their resistance movements will fall out of touch with the history here. We talked about the left-wing Islamist group Mojahedin-e-Khalq that went into exile in the West after 1979.[9] Ma, you must surely recall the tragic memories about their struggles with the theocratic government after they tried to oust the Shah, but these memories have now been almost completely rewritten, with them depicted as something like a cult conspiracy group. The young resistance movements no longer care to be associated with them and now you can only see the shadows of their existence in ads on porn websites—so tragic!

The night we left the police station, Adel went home and Noor and I went with Hedieh back to her house in Sanandaj; we exchanged our experiences of what happened in our interrogation rooms—at one moment laughing loudly at the authorities’ ignorance, in the next bragging to one another about the little tricks we used to handle their questioning; at other moments still, we sobbed together at the humiliation our friends had suffered. Looking back, we imagined that it must have been their frustration at not having enough proper evidence to arrest us that made them fly into flurries of rage like that. ‘I don’t fucking get it. You all aren’t after money, you don’t want fame, so what is it that you want? You all are just fucking messed up in the head!’ spat the middle-aged officer from Tehran who had questioned Hedieh after we had completed our paperwork and as we were getting ready to leave. We laughed bitterly, because nothing in their imaginations could grasp the picture of the better world we are after. They can’t even understand the fact that people have dignity and ideals outside personal gain! Later, we burned all printed matter related to the resistance and their words disintegrated into ash like an epitaph. The warmth we shared in comforting one another that night was so precious. But it was no longer convenient for Hedieh to continue hosting us, because now we were being tracked and followed even more closely, and we would probably bring trouble to any person with whom we came into contact. Noor and I didn’t know where to go, but the next night we decided to break free of the police cordon. While on the run, I could faintly hear the bombs in the direction of Iraqi Kurdistan.[10]

During the long wait at the airport, I got a call from Majid in Canada. He had heard about my situation from friends. ‘You have to leave immediately! Go through the Kurdish area and cross the border to Iraq, whatever you do, don’t go back to Tehran!’ ‘I’m not prepared to leave illegally; I don’t want to never be able to come back!’ ‘I know you haven’t been able to prepare, but you have to understand, this is going into exile! Exile does not give you time to prepare!’ He was forcing me to face up to everything I did not want to face up to, and we almost got into an argument. Those two hours on the phone left me feeling burned out. Majid even got Parva, who had once been locked up in a detention centre for a year, to phone me. After she was sentenced, she managed to get a reprieve but had to wear an electronic tag for two years and cut off contact with everyone. Just as the public and even the police were about to forget her, she quietly left and is now seeking asylum in France. ‘As long as I still hold the passport of the Islamic Republic, it will not matter where I go, I will still get chills from the feeling that the motherland is on my back. I can only make a complete break,’ Parva said firmly. She had once given up so much for the resistance: the studies she was just about to complete, her comfortable life. But in the elitist system of the West, it seems that hawking her victimhood is the only means for her to find a place for herself again.[11] I don’t want to leave, much less leave and not be able to return. Compared with that, staying in prison for a little while doesn’t seem so hard to endure. But how do I know whether it will only be ‘a little while’?

At last, I arrived on Kish Island. This island in the Persian Gulf seems to sit outside history. The sun shines brightly, the air is warm and humid, and there is no fury raging through the people, no violence from police. Meanwhile, those places now in history grow colder and colder, and the cold weather drives the women on the street to start putting on their headscarves. One after another, our friends from Tehran are taken away, accused for no reason. Those who haven’t yet been ‘disappeared’ slip into fear and restlessness, but the scariest thing is the distrust it breeds among us, making us estranged. Comrades try to guess who is the secret police informant who has ‘infiltrated’ a chat group. Those who are arrested and released are sometimes met not with consolation from friends, but with suspicion of being implicated by association. The explanation for deleting friends in messaging apps always sounds similar: ‘I’m different from you all. I am not prepared to be a revolutionary, don’t want to sacrifice myself!’

There are so many brave souls out there. They appear in images, they are talked about and praised, but there are also so many fears and weaknesses that we are yet to overcome. The excess of trouble can therefore only be concealed in the dark corners of the revolution; there is no place to set them down.

On New Year’s Eve, Mina came from Tehran to visit me on the island. That night, we slept in one bed and she painfully recounted how in the face of threats of punishment, friends began to waver about the revolution. Governance by fear had begun to take hold, dividing people from one another. She was isolated because she was more determined and more sincere. Venting her anger, she said that she was no longer willing to use her own legal knowledge to help friends who had just been ‘disappeared’. I cut off that bedtime conversation almost impatiently. Afterwards, I thought I must have been scared that she would see through to my weaknesses. The thing that tortures me most about my interrogation experience is the moment of betrayal. Under pressure, I gave up some participants’ nicknames, consoling myself that, as long as I didn’t say their real names, I wouldn’t really be revealing their identities. But I knew I was only deceiving myself. In that instant, the betrayal swallowed me whole, and part of my spirit and all I believed in collapsed. The pain of that guilt will always haunt me. When Mina was interrogated, she never gave up her phone or computer passwords, and every time she was asked something by the police, she fought back with silence and an unwavering gaze. We all want to embrace and transmit this kind of female image, but I think she could also be a little more tolerant and give our generation a little more time to learn how to live with fear. What I didn’t imagine, however, is that less than one week after I said goodbye to her, Mina would be arrested again.[12] In this past half-year, I never know whether each goodbye will be the last. How I regret that I cut her off that night.

I am reminded of the torment Katayoon suffered before being arrested. As the wife of a famous dissenter, she had to embrace her ‘wife of the Decembrists’ image. She gave up all her own activities and shouldered all that political pressure to support her husband and see out the cause he was unable to finish. That responsibility did not allow her an ounce of weakness or retreat. By the time we realised that she could no longer bear the burden, it was too late. Just before she was taken into custody, she fell into a depression and began hallucinating. Her face swelled up and she would hide away in a closet at home. Oh, yeah, today just so happens to be her birthday. I wonder how she’s spending it in jail.[13]

The smoke shield–creating news of the abolishing of mandatory headscarves and the morality police began to spread throughout the English-speaking world, and people outside began to call victory for the Iranian women’s revolution. But they didn’t pay close attention to all the arrests and imprisonments happening on the inside. On television, the Supreme Leader insisted that the resistance was a conspiracy by foreign agents and that they were urgently ‘seeking out the organisers’.[14]

The mood of resistance fades day by day. As for me, silence and self-punishment have not brought any peace, they’ve only made me number and more detached. What will come, will come. This time they didn’t weave an elaborate web to entrap me. I was being forced to frequently report my movements to the authorities and could only await my own surrender with my hands tied. And there was no interrogation. They had already contrived the list of crimes against me during these couple of months. The common charge of being a ‘foreign agent’, whether true or false, is not open to dispute. I was immediately brought back to Qarchak Prison in the south of Tehran to await my final sentence. They didn’t even give me time to go home and see you.

Mother, I am sure they will look for you, tell you that I am about to face horrible punishment to scare you, to have you urge me to plead guilty, just like they usually do. I know you will be afraid and worry about me, but you will also believe that I haven’t done anything wrong, won’t you? Our generation has not completed this revolution. But I think the only promise we can make to the next generation is: ‘The accused did not express remorse.’

‘The accused did not express remorse’ are the last words of 19-year-old protester Yalda Aghafazli. In November 2022, she was arrested and held at Qarchak Detention Centre for 10 days, during which she was beaten and tortured. She went on hunger strike, but after she was released chose to end her own life.

Mahsa

13 January 2023

Postscript

This story was written while I was hiding in Hainan, just as the zero-Covid policy was undergoing a reversal. A major wave of infections ripped through the country and many people lost their lives. Even before the zero-Covid policy had ended, however, the reality was that there were already difficulties controlling the spread of the virus. Opening up without any preparation seemed to be a ‘punishment’ for the masses who had clamoured with complaints during lockdown. Both the zero-Covid policy and opening overnight are symptoms of the same type of lazy governance, treating lives as mere statistics. The difficulty of retaining memory makes it easier to manipulate people’s perceptions. In public discourse, opposition to the first policy was construed as being responsible for the consequences of the later policy. At that time, people actively started to forget the anti-lockdown struggles, or even to curse the protestors. The sentiments of popular resistance that coursed under the surface in October and November have dulled to an unprecedented silence. Amid the wreckage of acute Covid-19 case rates and death rates, amid the condemnation and forgetting of the anti-lockdown protests, secret arrests continue. Fear made us unable to find one another, we didn’t know who had been taken away, and didn’t dare speak up in public for our disappeared friends.

After I left the country, I gave the rights to publish the version of the story with footnotes to Initium Media and Women4China, but at that time the embodied memory of fear still haunted me, and I dared not use my real name. Even though this annotated version was published outside the Great Firewall, it still slowly and quietly has effects inside the Wall. Some with similar experiences have begun to use the metaphor of Iran to write their own Tehran or Isfahan stories. The friends of those mentioned in the letter have begun using their Persian names from the story to talk about their recent predicaments. Amid intersecting histories, the metaphor of Iran has become real. As one person wrote after reading ‘A Letter from a Tehran Prison’: ‘Because of its bravery, Iran has become everyone’s Iran.’

Eventually, I successfully applied for a German visa from Thailand. After arriving in Berlin in March, I realised I had to make my own experience public within the Great Firewall, to bind this story to China’s reality. This is not only because it is the responsibility of a witness of history—all those people who have faced political persecution in this wave have had their voices taken away from them—it is also because if I were to continue using a metaphor, my own trauma would remain an open wound, unable to heal. Going public has indeed made waves within the Firewall. The Weibo reposting that occurred at the beginning of the year picked up again. With the help of the footnotes, those who had read the original as an Iranian story solved the riddles one by one. After passing through the winter and reading the story again in spring, the unfamiliar names and places alongside the familiarity of their details generated a terrifying feeling of realism. The unstated message behind the story—that the ‘reality’ of our world can only be spoken of when it is hidden within the ‘elsewhere’ and the ‘imaginary’—gives this piece of fiction an even greater realism. These two readings, a few months apart, together become a work of ‘non non-fiction’. But as to be expected, after less than one week, the text was also caught and fated to being ‘404-ed’. All reposts of the text shared on social media within the Great Firewall disappeared.

Our mother tongue has been completely disfigured, made obscure and ineffective by taboos. Impenetrable censorship has turned simplified Chinese into a language of lies and empty political propaganda. An indescribable monster. With its soaring tones and flailing rhythms, it reminds people that ‘knowing’ itself is a dangerous act. We are careful to communicate and express ourselves behind distorted codes and metaphors. Thoughts banished; ideas displaced. Memory is no longer an accumulative substance, but an iterative one: the old quickly overwritten or rewritten by the new, with no continuity or coherence. I often wonder whether a new form of writing will be born out of the disjointed experiences of our generation, whether language itself may have to be fragmented, deceptive, and alternating between reality and fiction, since our emotions and experiences undergo ruptures over and over again, and the ‘reality’ in which we live has to be hidden in ‘elsewhere’ and ‘fiction’ to be told.

When I heard that ‘A Letter from a Tehran Prison’ would be translated into English, I felt extremely uneasy. The subtleties of this text are probably only effective in the Chinese language. Even though I have been to Iran twice and have been closely following what is happening in the country, the metaphor has not been carefully researched or deliberated. Some of the details of the story would not be practically feasible in Iran. I intentionally did not verify information as I wrote, hoping the details of the story would spill out from the Iranian backdrop, creating fractures in the text to allow readers to grasp threads leading them back to our reality. With this English translation and the possibility of acquiring more readers, these spillovers may all become improper appropriations. Especially when the movement in Iran was so fearless, this story of mine, filled with fear and timidity, could be said to belittle the revolution in Iran. If I have caused any offence, I am deeply sorry.

21 March 2023 (Edited on 1 December 2023)

(Translated by Aaris WOO and Yixi)