Commons and the Right to the City in Contemporary China

This short essay tells the story of Dongxiaokou, an urban village in the northern outskirt of Beijing, infamously known in the press as the ‘waste village’ (feipincun). Until urban redevelopment projects accelerated its demolition in recent years, this informal settlement had been one of the biggest in the metropolis. Situated between the Fifth and Sixth ring road, around ten kilometres from the city centre, it hosted a massive population of migrant workers, who had made this place their home and used it as a base to enter the Chinese capital’s labour market.

The story of Dongxiaokou provides interesting insights into the process of commodification of land in contemporary China. The article engages with this issue and highlights, in particular, the tension between land used as a common resource by migrant workers and land utilised as a way to produce economic profits for real estate development. There are at least two good reasons why this story is worth telling—one related to the status of land use rights in China; the other to the nexus between labour and migration in the country. This account of Dongxiaokou reasserts the centrality of an old question: in a geography where capitalism brings about a growing commodification of space, who owns the right to the city? In other words, if we consider the urban space as a common resource, who has the right to use it and under what conditions?

Land Rights and Migrant Labour

Surprisingly enough, while in the last decades China has undergone a number of subsequent shifts towards economic liberalism, land somehow remains a conundrum for the country’s ‘socialist market economy’. While land has certainly been subjected to the effect of the marketisation of the economy, it has also remained strictly tied to the Party-state. Today there are two main types of land property rights in China. While urban land is formally owned by the state, rural residents exercise collective ownership in the countryside. In theory, rigid regulations control the use of this resource; in practice, however, ambiguity in the legislation has resulted in an empowered Party-state, which has ended up holding sway on land-related decisions in both cities and countryside.

A common practice in many rural villages involves the development of collectively-owned land into urban and commercial functions as a way for local administrations to create new streams of revenue. While some localities have been more successful than others, this phenomenon has appeared almost everywhere in the country. In particular, these practices have multiplied in border areas between the city and the countryside, where many rural villages have been completely transformed in their geographies. This rural-urban friction has also led to another phenomenon driven by the increasing marketisation of the economy and the process of commodification of land. The sprawling of metropolises into suburban areas has resulted in the recurrent inclusion of rural villages into urban districts. Rural land is thus subjected to a two-fold process of commodification. First, it is informally developed into urban and commercial functions as a means to make a profit for rural areas. Second, these hybrid spaces are again subsumed by urban redevelopments.

The story of Dongxiaokou, a small rural village that in a few years became one of the largest informal settlements in the Chinese capital, is particularly revealing of both dynamics. In the early 2000s, the village rented most of its land to migrant workers coming from outside the municipality of Beijing. Its proximity to the city centre made it a convenient place to settle down and find work opportunities in the metropolis. When the first migrants arrived, local cadres welcomed them and accommodated the newcomers in uncultivated fields, which were rented out as a way to drive new revenues into the village.

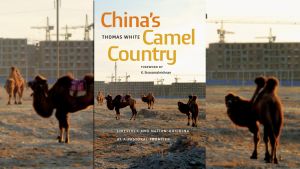

Wealthy migrants rented big plots of land that they then divided and sublet to less well-off migrants, who in turn established their dwellings and economic activities in Dongxiaokou. Very quickly the village population grew from little less than two thousand people into an agglomeration, according to some sources, of almost thirty thousand inhabitants. Interestingly, Dongxiaokou quickly became a local hub for waste recycling activities growing in scale and scope. As one of my informants claimed in a personal communication, in few years Dongxiaokou was transformed into ‘one of the biggest scrap distribution centres (feipin jisandi) in the entire country.’

A complex network of buyers and suppliers for all sort of waste materials developed in the village. During the day, local recyclers roamed the wealthy neighbourhoods of Beijing in search of valuable products, such as used mobile phones or old compressors. In the evenings, they came back to Dongxiaokou to resell their products to middlemen who, in turn, resold them to manufacturing companies in nearby regions. A large number of complementary businesses, such as mechanic workshops, logistics firms, groceries, and restaurants, also quickly flourished in the village.

Hundreds of family-owned enterprises dominated the landscape. They all looked more or less the same. Behind a metallic gate was a rectangular courtyard where old newspapers, waste wood, plastic bottles, used electronics, or anything else with a commercial value was stored. In one of the corners of the yard there was always a small building, usually composed of two rooms, where an entire family lived. Sometimes a dog was chained to one of the walls to guard the yard.

A New Generation of Petty Capitalists

Interestingly, while academia and the media have paid much attention to different generations of migrant workers in their role as wage-labourers, the rise of Dongxiaokou paints a less familiar picture. It tells the story of small family-owned firms and self-employed entrepreneurs, or in other words, petty capitalists. It is a story of what some define as the informal economy: a heterogeneous sector that crosses many different industries, and employs a large proportion of the population in contemporary China. It is not my goal to romanticise this phenomenon, which raises serious questions of occupational health and safety, as well as issues of local citizenship and environmental justice, but rather to underline what I believe to be one of its most peculiar characteristics. Migrants in Dongxiaokou—at least a good portion of them—enjoyed a relatively high level of freedom and mutual support, being part of a local society that conceived of their resources—labour and land—as means of common subsistence.

Dongxiaokou was not an isolated case. A report by the United Nations published in 2013 estimated that the informal recycling sector in China comprised twenty million people, and that it was organised in a myriad of informal settlements scattered all over the country. While numbers certainly cannot give an accurate account of the great variety of businesses that this industry creates, they are nevertheless useful to provide a general idea of the magnitude and impact that these activities had, and continue to have, on Chinese metropolises. This involves the creation of employment opportunities on the one side, and the production of physical landscapes on the other side.

Dongxiaokou was not a new phenomenon either. In their work on the ‘Henan village’, Béja and colleagues documented the emergence of these urban and economic spaces as far back as the 1990s. The authors analysed a settlement not too far from Peking University—now long demolished—in many ways similar to Dongxiaokou. They did so through the notion of desakota (desa meaning ‘village’ and kota ‘urban’ in Bahasa), a concept that was first employed in studies on the urbanisation of Southeast Asian countries. In Indonesia, the metropolitan sprawl had produced a peculiar combination of rural and non-rural activities, where areas dedicated to the production of rice were mixed with the urban landscape. Drawing a parallel with the Indonesian context, the authors described the Henan village as a peculiar Chinese desakota.

The fate of Dongxiaokou was decided in the 2000s. This space on the urban periphery, which had been transformed through the agency of a group of migrant workers, and which provided a fundamental service to the city—waste recycling—did not resonate with the conceptions of modernity that official planners held for Beijing. When urbanisation reached the borders of Dongxiaokou, space had to be made for the new real estate projects. As a result, demolitions of the ‘waste village’ of Dongxiaokou accelerated in 2015. The place that previously buzzed with economic activity was again geographically transformed. Workshops that were filled with all sort of valuable products became empty fields, as their occupants had to relocate to other parts of the city. Roads were silent, except for the sounds coming from the new infrastructural works planned by the municipality. Having lost their usual clientele, shops closed down, and most dwellings were levelled.

A Social Community

As the story of Dongxiaokou suggests, two different levels of urbanisation exist in contemporary China. The first is a process mediated by the state that operates inside the administrative boundaries of the city; the second is an unofficial one, which goes beyond these boundaries and occurs at the margins of the metropolis or in the countryside. Here, migrant workers, attracted by the possibility of improving their material lives, enter Chinese metropolises and create particular urban economic landscapes, while suburban villages benefit economically from their presence. Yet, official planning recurrently subsumes these spaces.

These different modes of urbanisation also mirror contrasting ways of creating and living in the city. Enclaves of informality—and the specific use of land operated in urban villages—reflect the way less-privileged groups make a livelihood, rather than a strategy to produce profits from land development. While they come from poorer rural regions and moving into metropolises, friendship and kinship networks support the adventures of these migrants who lack any basic formal right to the city. As a dweller in Dongxiaokou clearly pointed out, the social community that inhabited Dongxiakou provided important support to migrants. In his words: ‘Being here is like being back home… Like this, it is easier to do our business.’

As this quote suggests, urban villages are microcosms of people and relations that represents a social community and not only economic outcomes. Here the physical and social dimensions of land are strictly intertwined with the everyday livelihoods of the people that inhabit these spaces. Their redevelopment is thus a process that brings about a destruction of these communal spaces, highlighting once more the need to ask an old—but urgent—question: who has the right to the city in contemporary China?