Industrial Landscapes of Socialist Realism

‘As a Nation, We Won Our Rights, Our Dream. Not So Where Capital Reigns Supreme,’ E. Maloletkov, Moscow 1957

To many in the twenty-first century, the industrial landscape appears as one of the most alien of art forms. Yet, the billowing fumes of endless smokestacks or the web of piping from a glistening petroleum plant once made the best representatives of socialist realist painting. Socialist realist art portrayed ideal life in socialist states—anchored in communism, class-consciousness, and loyalty to the party and the people. While many Soviet works showed elements of the genre decades earlier, artists and theorists from the Soviet Union only began officially promoting socialist realism as a ‘true and historically concrete depiction of reality in its revolutionary development’ at the Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934, leading to its spread around the world. The genre then arrived in China and Korea as an already stylised form with a long history. While in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) it fell into oblivion during the reform period, it still continues to dominate in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) today.

In the Soviet Union, artists included industrial landscapes in the background of propaganda and artwork. The backgrounds reflected the life, and idealised the ambitions, of the working class. There was a marked emphasis on klassovost, sometimes translated as class-consciousness. Exemplars of the genre also showed partinost, loyalty to the party and its principles, and norodnost, the ambitions of the people or nation. While socialist realist industrial landscapes remained at the margins of the socialist realist genre in the Soviet Union, in the PRC and the DPRK, both of which have a long artistic tradition of landscape painting, these industrial scenes became the focus of artists’ work for a short time in the mid-1970s. This essay examines the legacies of Song Wenzhi (1919–1999) and Chōng Yōngman (1938–1999), the most accomplished artists of industrial landscapes in the two countries, showing how different revolutionary histories have led to a divergence in legacy and achievement.

‘Taihu’s New Look’, Song Wenzhi (1979)

Song Wenzhi and Industrial China

In China, it was Song Wenzhi who produced the most popular examples of socialist realist industrial landscapes. Song was a classically trained artist with a strong background in landscape painting. Although he was forced to spend the first years of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) in a factory, he resumed painting in 1972. In 1973, he was appointed deputy director of Nanjing’s Provincial Fine Arts Work Team. There, he continued to create beautiful landscape paintings. However, his art began to show elements of industrial modernity, sublimely sliding between traditional Chinese landscapes and socialist realist images of industry.

In many of Song’s paintings, he introduced modern elements as a subtle but dominating feature, such as in ‘Taihu’s New Look’ (taihu xinzhuang). Song only fully surrendered to the industrial landscape genre in a few paintings, producing images that not only stand out as excellent examples of traditional Chinese painting, but also remain iconic reminders of the time. Of these, the most memorable is his 1975 masterpiece ‘Daqing Blossoms along the Yangzi River’ (yangzijiang pan daqing hua). Through Song’s reformed classical technique, mountains metamorphose into factories and flowers blossom as the billowing clouds from a forest of smokestacks.

Song did not continue with the genre. Whatever compelled him to create these paintings—whether it was the watchful eye of his superiors, the pull of a revolutionary ‘market’, or his own experiences at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution—at the end of the Maoist era he turned back to traditional landscapes. While continuing to sketch the occasional power line, he never returned to the subject of industrial beauty. The genre had no place in the opening up and reform period that China entered in 1978. This was not the case in the DPRK, however, where the revolution never ended.

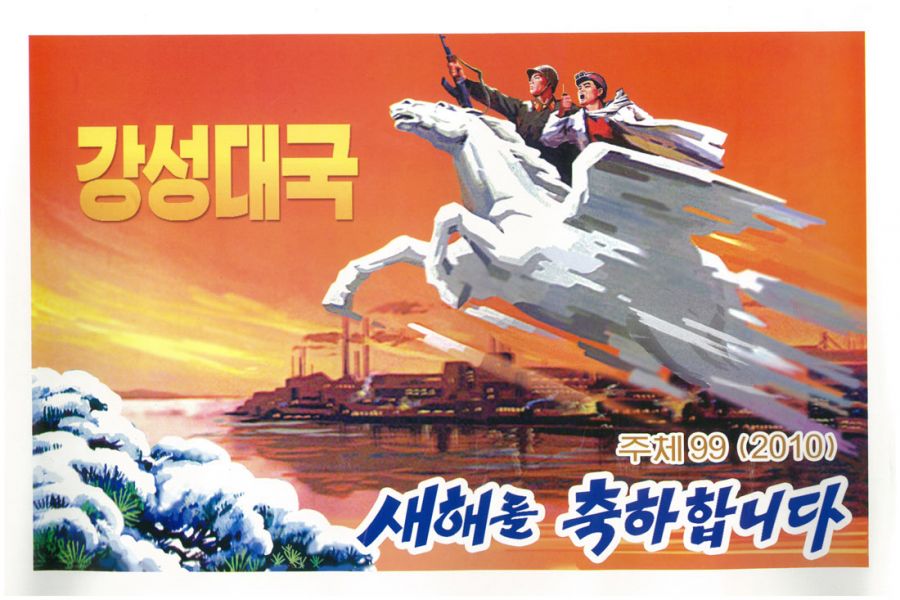

(1) ‘Evening Glow over Kangsōn Steelworks’, Chōng Yōngman (1973). (2) ‘The worker and the soldier race forth on a chollima. A strong, great nation! Wishing everyone a Happy New Year, 2010.’ (3) The ten won bill of the DPRK.

Chōng Yōngman’s Depiction of History and the Workers

In 1973, just two years before Song painted ‘Daqing Blossoms’, one of the most celebrated North Korean painters Chōng Yōngman produced an industrial landscape that captivated the country and led to a reconsideration of the genre of Chosōnhwa (Korean Painting) (Lee 2014b). Largely due to the historical, artistic, and ideological success of ‘Evening Glow over Kangsōn Steelworks’ (gangseon-ui-no-eul), Chōng later became vice-president of the Mansudae Studio and a chairman of the central committee of the Korean Artists Federation.

The Kangsōn Steel Mill was the birthplace of the Chollima Movement, an ideologically driven productivity campaign initiated by Kim Il-sung when he visited the mill in December 1956. Unlike China’s Great Leap Forward and the Stakhanovite Movement of the Soviet Union, North Korea’s Chollima Movement has remained at the centre of national identity. The chollima refers to a horse of unimaginable speed in East Asian legends, indicating the astounding potential of the North Korean worker. Images of the horse are still evident everywhere in North Korea today, but Chōng’s painting of the factory is just as much a symbol of this decisive period in DPRK history.

‘Kangsōn Steelworks’ was Chōng’s most important work, marking a departure from the simple and powerful ink Chosōnhwa and creating an iconic image that is still a common sight today. The image once featured on the ten won bill; it also serves as a backdrop for New Year’s posters, and greets visitors to the Korean Museum of Art in Pyongyang. Moreover, the use of ‘Kangsōn Steelworks’ in official media ensures that tourists to North Korea inevitably come across this mesmerising painting in either its original form, or as the background for numerous posters that have since incorporated the classic painting in their own imagery.

‘Daqing Blossoms along the Yangzi River’, Song Wenzhi (1975)

Real and Ideal Beauty

Socialist realist landscapes should concentrate upon the ideal reality—rather than the real reality—for the worker, the scientist, and the farmer. Nowhere is this better achieved than in the DPRK. The socialist realist industrial landscape has long fallen out of fashion in Russia, and no longer has a place in post-socialist China, where images of smokestacks are reminders of the problems of air pollution, rather than of the glorious worker. However, the landscape still holds its symbolic value in Pyongyang, where the state glorifies the role of the worker in the continued struggle to maintain and improve the nation and the Party.

Although Song Wenzhi adapted traditional Chinese art in an innovative and a compelling fashion to produce beautiful paintings of the country’s industrial accomplishments, Chōng Yōngman’s ‘Kangsōn Steelworks’ has stood the test of time. Up to this day, it continues to captivate the people due to its vivid portrayal of industrial beauty, and finds official support due to its ideological correctness in relation to the political discourse of the ruling Party. The piece’s relationship to the historical significance of the Chollima Movement cements it as an exemplar in socialist realist art—uniting the ambitions of the Party, the nation, and the working class in a way that could not be achieved in the context of China’s more contentious and complicated revolutionary history.

‘Once Again, Let’s Improve the Life of the People by Producing All Sorts of Things!’

But Chōng’s achievement is not only ideological. Even before global concerns with climate change, few found beauty in images of polluting gases billowing into the air. However, those of us who have stood on concrete rooftops and watched the sun set in a torrent of colours filtered through a wall of effluvia know that these paintings are more than markers of material development. They are beautiful works of art.