Visualising Labour and Labourscapes in China: From Propaganda to Socially Engaged Photography

What can photography bring to our understanding of labour in China? This question needs to be addressed taking into account the role and possibilities of photography more generally, its development over time, and the history and special conditions in China. After 1949, political control over image production in China created a visual hegemony that glorified socialism and class struggle, while rendering social problems, inequalities, and injustices invisible. However, like in so many other fields, the reform period has enabled a growing and diverse group of people to challenge earlier prescribed visual aesthetics and ideological control. Photographers today experiment with new ways of documenting Chinese society, and also address hitherto invisible issues as well as new problems. Economic and social reforms have created new types of workers, for instance migrant workers, more precarious labour conditions, for example in factories in the South and in private mines, and new forms of marginalisation and exploitation, such as illegal work within the sex industry.

These socio-economic developments have drawn the attention of domestic and foreign photographers alike, such as Edward Burtynsky—working on Chinese topics like the steel and coal industries, manufacturing, shipyards, recycling, and the Three Gorges Dam—and Sim Chi Yin working on topics such as gold miners and migrant workers (Estrin 2015). Digital photography, the Internet, social media platforms, and the expansion of smartphones, not only have provided professional photographers with new possibilities, but they also have enabled ordinary Chinese citizens and workers to document their lives and circulate these images online. Today a wide range of photography tackling social problems and labour conditions can be seen on the Internet, in art spaces, as well as on social media platforms. If, as the filmmaker Wim Wenders (quoted in Levi Strauss 2003, 1) argues, ‘the most political decision you make is where you direct people’s eyes,’ China indeed has gone through a visual revolution challenging the political gaze and visual hegemony. This being said, however, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) still maintains a strong interest in—and the means to—control and censor both the written word and images.

This essay discusses how photography can serve a twofold purpose, as both a valuable historical record that helps us understand how ideology and politics have shaped images of labour and the working class in China, and as an important affective and intellectual tool to analyse current labour issues.

Photography, Social Engagement, and Calls for Change

In the West, photography has long been regarded as a tool to create awareness of social problems, injustices, inequalities, and the life and struggles of marginalised groups of people (Bogre 2012; Franklin 2016; Levi Strauss 2003). Since the late-nineteenth century, documentary photography and photojournalism have addressed topics such as slum housing, landlessness, child labour, poor working conditions, poverty, and migration. Socially engaged photographers and photojournalists have on their own accord or in collaboration with scholars and civil society actors, including news media, photo agencies, and NGOs, documented and uncovered social and political problems with the aim to create awareness and support for social and political change.

In the field of documentary photography on labour issues, one of the earliest and most well-known photographers is Lewis W. Hine, who in 1908 was commissioned by the United States National Child Labor Committee to document child labour in the country. Another example is Dorothea Lange, who during the American depression in the 1930s, together with the economist Paul Taylor, worked for the Farm Security Administration to document the causes and consequences of agricultural intensification and exploitative factory farming. A more recent example is Sebastiâo Salgado, who started out as an economist but in the late 1970s decided to devote himself to photography in the belief that it could be more powerful than pure academic work. While Salgado has been criticised for aestheticizing suffering, he has also been widely defended and praised, and in 2010 he was awarded the American Sociological Association Award for Excellence in the Reporting of Social Issues. Salgado maintains a strong belief in the power of photography to give rise to debate and action: ‘What I want is the world to remember the problems and the people I photograph. What I want is to create a discussion about what is happening around the world and to provoke some debate with these pictures (Salagado 1994).’

However, the increasing accessibility of photographs has created its own set of challenges. Already in 1974, W. Eugene Smith—who among other things is famous for his photographs of the victims of the Minamata mercury scandal in Japan—expressed awareness of how the sheer number of photographs can numb people, although he ultimately held the view that photography can be an important tool for critical thinking. In his words: ‘Photography is a small voice at best. Daily, we are deluged with photography at its worst, until its drone of superficiality threatens to numb our sensitivity to all images. Then why photograph? Because sometimes—just sometimes—photographs can lure our senses into greater awareness. Much depends on the viewer; but to some, photographs can demand enough of emotions to be a catalyst to thinking’ (quoted in Franklin 2016, 201). This emotional or affective quality of photography is also the reason why so many NGOs and activists today make use of photography in their work.

As a result of the digital revolution, we are today surrounded by ever more images that compete for our attention, and thus visibility remains a question of politics and power relations. Susan Sontag (2003) has argued that the proliferation of images of violence and pain can result in ‘compassion fatigue’ that undermines our abilities to feel, connect, and act. Images may thus hinder, rather than foster, action and solidarity, creating a distance that prevents connectivity and civic engagement. Other scholars and photographers have challenged her conclusion, however, and believe that photography can still play an important role in awareness raising, civic engagement, and humanitarian and political activism (Bogre 2012; Franklin 2016; Levi Strauss 2003). One needs to distinguish between images that play on people’s sense of guilt and give rise to pity, charity, and good-will, and images that provoke outrage and calls for more radical social and political changes. Moreover, one also needs to distinguish between images that portray people as victims and images that portray them with dignity and agency.

From Visual Hegemony to New Visualities

The CCP understood early on that photography can be useful in ideological work and serve as a propaganda tool (see, for instance, Roberts 2013 and Wu 2017). The proper role of photography from the perspective of the CCP was laid down in different speeches and directives, which came to inform Chinese photojournalism in the three decades that preceded the reforms. Photographers were called upon to show the progress and success of communism by documenting technical advances, new factories, and large infrastructural projects. It was not possible to take and publish photographs that hinted at social problems, hardships, or resentments, as this would have been seen as a critique of the political system. For this reason, photographs of the Great Famine of the early 1960s do not exist, but there are ample photographs celebrating the Great Leap Forward and its advances in steel production. In the photographs of the 1950s and 1960s, workers are depicted as heroic and strong, toiling to build the New Socialist China with commitment and revolutionary fervour. They are physically sturdy, well-dressed and clean-faced, and engage in difficult work without flinching. The photographs portray the strength and collective spirit of the working class without hinting at any difficulties or poor working conditions.

With the end of the Cultural Revolution and the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, the role and content of photography began to change. Photojournalists were inspired by the shifting ideological and cultural landscape, and began to experiment with new aesthetics, resulting in the appearance of a new humanitarian realism in photojournalism. At the same time, new artistic uses of photography—inspired in part by the influx of the works of Western photographers—appeared, while family photography became less political and more individualistic in character. Furthermore, the increasing affordability of cameras led to the emergence of a new generation of photographers, artists, and enthusiastic amateurs.

Since the late 1990s, we have seen a growing number of socially engaged photographers who address societal changes and problems, as well as photographers who embark on more personal and artistic explorations. Special photo journals, art spaces, and photo festivals, have given photographers new platforms to showcase their work (Chen 2018). Socially engaged photographers, such as Lü Nan (known for his work on mental patients), Zhang Xinmin (who was among the first to document migrant workers in Guangdong in the early 1990s), Nie Guozheng (who has documented the life of miners), and Lu Guang (famous for his work on the Henan HIV crisis and environmental pollution), have addressed topics and groups of people that previously received scant attention. Many NGOs—Project Hope working on rural education was one of the first—also began to make use of photography to draw attention to their work. The digital revolution, including the Internet, social media platforms, and smartphones, has enabled more people to document their lives and personal memories. On social media, especially Sina Weibo, Chinese citizens have been exposed to images of groups of people and issues that the traditional media are often still silent about, such as the struggle and plight of petitioners, trafficked children, and villagers who have lost their land (Svensson 2016).

Although initially reluctant to take to Weibo, workers, activists, and labour NGOs now use the platform to share photographs about their activities, including protests and strikes. Labour NGOs have also encouraged and trained workers to document their life and work, and have organised a variety of exhibitions (Sun 2014). The Love Save Pneumoconiosis Foundation, an organisation that opened its Weibo account in 2011, has actively used photos and videos of migrant workers suffering from the deadly work-related lung disease. Some migrant workers afflicted by this illness have also begun to use social media to circulate information and images of themselves and their lives. These photos and videos show the workers’ weak and emaciated bodies and reveal the seriousness of their condition, arousing empathy and support. Nonetheless, it is beyond doubt that most workers use their smartphones more for fun than as a tool to raise awareness about labour issues (Wallis 2013; Wang 2016).

At the same time, a more activist type of photography—which could be described as inverse surveillance or ‘sousveillance’—has developed thanks to new digital technologies and platforms. Although the digital revolution has brought about new forms of visualities and enabled more people to make and circulate their own photographs, the Chinese state can still control and prevent the circulation of unwanted content. This is happening at the same time as the sheer quantity of information available is making it difficult for these images to be seen and actually have an impact.

Reading Labour Issues in and through Photography

How can we read photography in the context of Chinese labour? In 2008, Susan Meiselas and Orville Schell brought together the work of 18 Chinese photographers in the exhibition Mined in China which was first shown in the United States and later also in China. In 2011, a new expanded exhibition called Coal+Ice was first shown in the Three Shadows Art Centre in Beijing before travelling to other places in China and the United States. Both exhibitions were sponsored by the Asia Institute in New York. These exhibitions included historical photographs from China Pictorial (Renmin Huabao) as well as contemporary photography from the 1990s and 2000s. Historical photographs from China Pictorial and other news sources provide rich information about the view and role of the working class during the Mao era but often less information about actual working conditions. The range of photographs illustrate both the changes in visual representation of miners as well as their changing working conditions.

One representative photograph from 1969 shows a group of miners, including a few women, standing and sitting on the underground track leading into a mine. They are not working, however, but busy reading Mao’s Little Red Book and holding a large portrait of him. The photograph is clearly staged to showcase how studying Mao is helping and inspiring the miners in their work. The miners are well-dressed and clean-faced, and the photograph provides no indication of hardship. Instead, it provides a reminder of how in the Maoist era ideology permeated all workplaces, and how miners were both celebrated and disciplined at a time when work was considered ‘glorious’.

This and other historical photographs provide an interesting contrast to the more contemporary photographs in the exhibition. The weakening of the grip of ideology over photography has led to new aesthetics and ways of documenting the life and work of miners. At the same time, the reform period has also led to the emergence of private mines and, in many cases, worsening working conditions. The workforce today includes migrant workers with less skills and lower social status than their predecessors or their counterparts in state mines. Socially engaged photographers capture these changes in the nature and status of the work. For instance, Niu Guozheng’s photographs in Henan and Geng Yunsheng’s photographs in Yunnan since the 1990s both reveal the precarious situation of those miners who struggle to make a living in a dangerous line of work. Their photographs show bare-chested miners covered in soot engaging in taxing manual labour, carrying buckets of coal in small, private mines that one may assume are not very safe.

One early striking photograph by Niu Guozheng—included in the celebrated 2003 exhibition Humanism in China—shows a teenage boy covered in soot on a heap of coal and rocks. He stands with a cheeky and self-confident smile, basket on his arm, dressed only in a pair of shorts and sandals. Slightly ajar on his head, adding to the sense of casualty and humour, sits a helmet that is more for show than for safety. The image works on a number of levels. On the one hand it raises questions of working conditions, safety, and underage miners; but at the same time it reveals the boy’s pride and resourcefulness, and acknowledges his agency.

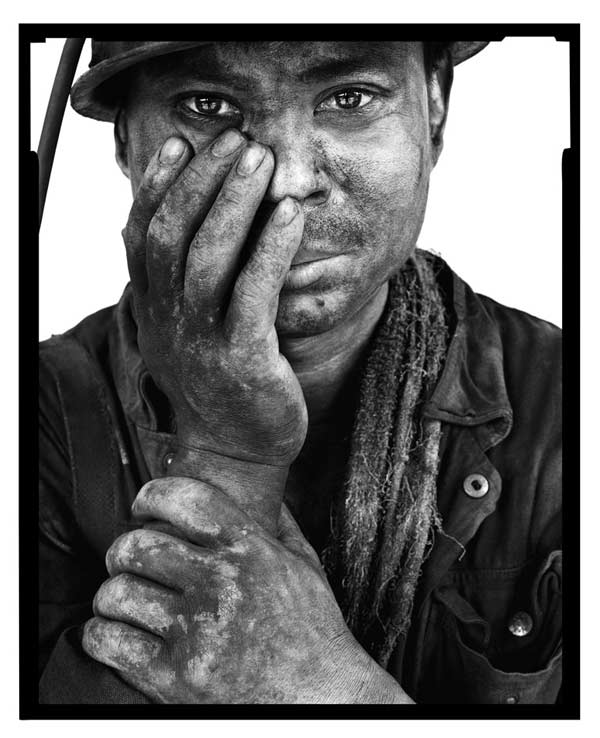

Showing the more negative and dangerous aspects of mining, Zhang Jie has taken photos of families holding photos of family members who have died in the mines. Wang Mianli’s photographs, in contrast, portray technically advanced mines—seemingly mostly state owned—where luckier miners work. These photographs privilege the physical settings and the machinery rather than the people working there, and through their composition and colouring give a somewhat techno-optimistic image of the mining industry. Another photographer, Song Chao, worked as a miner himself before taking up photography. His portraits of miners in black and white turn our attention from the mining industry to the individual miners themselves. Although the men are dark and dirty from the soot, their individual character, pride, and strength stand out, and the photos end up highlighting their agency.

These photographs remind us that the mining industry is highly diverse, with quite different working conditions and classes of workers. More importantly, the different styles of the photographers included in the exhibition show how Chinese photography today has diversified and become more individualistic in character. The exhibition obviously can be read and probed in many respects, and it indeed gives rise to a number of questions, some of which can only be answered by turning to academic works and media reports on the mining industry. Nonetheless, the photographs work more affectively than mere text and facilitate both awareness and engagement.

Building Empathy through Photography

Academic work and statistics often fail to capture the lived and embodied experiences of labour in different times, conditions, and places. In the best of circumstances, photography can provide a deeper, more empathic understanding that fosters respect and solidarity. It can furthermore serve as a catalyst for critical thinking and theoretical reflection. Through photography researchers and students of labour can get closer to subjects, sites, and topics that might otherwise be closed and out of reach to them.

Photography, however, may also hide or fail to explain larger institutional and structural contexts and issues. For this reason, one needs to have the necessary background information in order to critically read and analyse visual representations of labour. When looking at photographic records, we need to ask ourselves some critical questions: what are the limitations of photography? What is invisible or has been left out? What photographs are missing? Are workers depicted as victims or as agents of change? Who is taking these photographs and why, and does it matter? Only if we reflect on these questions, will we be able to critically understand the power of photography for engagement and solidarity.

The Mined in China exhibition can be seen at: http://www.minedinchina.com/.