Undoing Lenin: On the Recent Changes to China’s Ethnic Policy

There has been a lot of ink spilled over recent weeks on the changes to ‘bilingual education’ policy in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (IMAR) of China, and protests among ethnic Mongolians in response to what is feared might become the first step in the eventual erasure of the Mongolian language and identity. For this reason, I will not delve into the specifics of the immediate matter, which has been covered comprehensively in Christopher Atwood’s ‘Primer’ in the Made in China Journal, a joint letter from anthropologists Caroline Humphrey and Uradyn Bulag, an essay from the Red Horse Reading Club (红马读书会) that has been translated from Chinese into English, and op-eds by Gegentuul Baioud and Li Narangoa. Instead, I want to elaborate one point that bears repeating and that is missing from most of the coverage of what is happening: the current language policy is in direct contradiction to the views Lenin held in the last years of his life on national autonomy and a departure from the political vision of the early Mao years that is still enshrined in the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Instead it is a turn toward a Chinese national ‘multiculturalism’ inspired by the United States. This is not a good thing.

This intervention is a response to three untenable positions: 1) Empty talking heads who repeat the catechism that Xi is enacting a return to Mao, because they reduce all politics to the question of power and therefore understand neither; 2) All of the red-baiters in the United States who emphasise the ‘Communist’ in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and are attempting to reheat the stale leftovers of the Cold War (afraid of the rising socialist and communist consciousness among millennials domestically); and 3) those on the left whose logic inverts that of the second group, believing that China is indeed ‘Communist’, which absolves it of the sins of settler colonialism, capitalism, and environmental destruction.

Down with Great Power Chauvinism!

In the final years of his life, Lenin declared ‘war to the death on dominant-nation chauvinism’ (Lenin 2017, 111). Presciently terrified that the Bolsheviks would continue the Tsarist mentality and imperialist tendencies of Great Russian Chauvinism, Lenin mused whether the Soviet state apparatus remained the one ‘we took over from Tsarism and slightly anointed with Soviet oil’ (1975, 720) or whether it could be destroyed and remade along communist principles. These principles would require a definitive rupture with chauvinist tendencies that Lenin saw all around him. To provide one example pertinent to the issue of language education, Lenin (1975, 660) unequivocally rejected the idea of Russian linguistic dominance at the expense of national languages: ‘At the Commissariat of Education, or connected with it, there are communists who dare say that our schools are uniform schools, and therefore don’t dare teach in any language but Russian! In my opinion, such a Communist is a Great Russian chauvinist. Many of us harbour such sentiments and they must be combated.’

From the above passages, two important points emerge. First, communist revolution is not simply a change of who is in power but must be a transformation of the relations of power—in 1945, Mao’s answer to the question of how to break free from the cyclical history of dynastic rise and collapse (周期轮) was ‘democracy’ (Barmé 2011). Second, for Lenin, communism must be international, and therefore multilingual, or it would be nothing at all.

Lenin’s rejection of great power chauvinism needs to be understood alongside his defence of the independence of smaller nations. Historian Moshe Lewin (2005, 87; also see Lenin 1975, 722) describes Lenin’s view of the different forms of nationalism: ‘In order to make amends for the wrongs committed against the small nations, the big nation must accept an inequality unfavourable to itself.’ Following these principles, the Central Committee in Moscow would have to win the goodwill and trust of its neighbours who historically suffered under Tsarism; internationalism could not be strong-armed into being. Late in 1922, Lenin grew increasingly alarmed by reports that Stalin, then Commissar for the Nationalities, and Ordzhonikidze, then head of the Party’s Caucasian bureau, were doing precisely what he feared—using brutish methods to bring the Georgian Central Committee in line with Moscow’s plans for economic and political integration. Against Stalin’s plan to include the independent Republics in the Russian Federation as ‘autonomous Republics’, Lenin insisted that national independence must be preserved. We know from history that although Lenin’s proposal was adopted, it was in name only.

Lenin’s concept of ‘Great Russian Chauvinism’ was translated into the Chinese context as the tendency of ‘Great Han Chauvinism’ (大汉族主义). Following Leninist principles, the CCP also realised that it needed to win the trust of minzu (民族) in the borderlands as a matter of survival; I will leave minzu in the Chinese because it encompasses a range of contested meanings and approximate translations ranging from nation/nationality to ethnicity (as it is currently officially translated), and its reformulation into shaoshu minzu 少数民族, which connotes both national minorities and minority nationalities (Bulag 2019, 147). During the Long March (1934–35), Red Army forces traversed Miao, Yi, and Tibetan territories and needed to differentiate themselves from the Nationalists (Bulag 2012, 100). To accomplish this goal, the Communists—not without controversy and debate—formulated the distinction between ‘good Han’ (好汉人) and ‘bad Han’ (坏汉人) to form alliances and friendship with non-Han peoples (Bulag 2012, 95). The ‘good Han’ were those who fought ‘against imperialist tendencies within one’s nation’ (Bulag 2012, 97), rejected all violent manifestations of Han chauvinism, and supported the self-determination of non-Han minzu, in direct contrast with the Nationalists’ assimilationist vision of the zhonghua minzu (中华民族) or Chinese nation as a large family. Although the Communists also debated the idea of a zhonghua minzu, it did not become a political concept until its recent appearance as the dominant vision of the nation under Xi (Bulag 2019). Despite its Nationalist pedigree, to underscore its newness, the term zhonghua minzu was only first mentioned in the PRC Constitution in 2018 (Ma 2019).

Although it is too complex to go into the historical details of the period, the main point I want to distil is that the related struggles against Han chauvinism on behalf of minzu autonomy are built into the foundation of the People’s Republic. Although the historical record did not live up to its ideal, as it was an unstable balance of power subject to fluctuating discursive environments and political pressures, the institutionalisation of minzu autonomy was still a relatively bright spot of the early Mao period—especially when compared with the abhorrent treatment of indigenous peoples in North America and other settler colonial contexts (Estes 2019; Dunbar-Ortiz 2015). This also means that minzu autonomy is entirely a product and category of the modern Chinese state.

The Case of Inner Mongolia

In 1947, the ‘Inner Mongolian Autonomous Government’ was established as an autonomous representative of the Inner Mongolian people within an (implicitly) federal Republic of China. It contained recognisable hallmarks of sovereignty—its own flag, basic law, ‘Prime Minister’, ‘army ministry’, and so on. It was not until December 1949 that all of these attributes of locally derived sovereignty were dismantled and recomposed as the IMAR, explicitly integrated as a local government in a unitary People’s Republic of China (see Atwood 2002, 2004; Bulag 2012; Liu 2006).

Japanese occupation of Inner Mongolia from 1931 to 1945 permanently heightened Mongol expectations. The Japanese militarists created autonomous provinces and states in what is now Inner Mongolia; after 1945, the Chinese nationalists aimed to eliminate them and go back to the pre-war policy of settler colonialism and assimilation of the Mongols. Meanwhile the Communists won crucial support from Mongol nationalists by being willing to accept these Japanese-era Mongol autonomous institutions as the nucleus of a new Communist-style autonomous government. Here, too, the parallels with Lenin’s time are worth noting: against the majority Bolshevik opinion that local governments set up under German (Ukraine), Turkish (Transcaucasia), and Japanese (Buryatia) auspices were reactionary enclaves of local nationalism that should be eliminated, Lenin was a very powerful voice in the wilderness arguing that the Bolsheviks needed to respect and work with autonomous local institutions, to avoid the project of internationalism becoming a Soviet version of imperialist chauvinism.

In this historical context, Mongolian language education was indispensable to autonomy. Even though he personally did not speak Mongolian, Mongolian language education was of paramount importance to Ulaanhuu (乌兰夫, whose name means ‘red son’ in Mongolian), Inner Mongolia’s most influential political figure, who served as the Communist Party Secretary of the IMAR from 1947 to 1966, was promoted to Vice-Premier in 1954, and later became Vice-President of the People’s Republic from 1983 to 1988. For Ulaanhuu and his Mongolian comrades, it was necessary to continue the legacy of the previous regime and allow for primary and middle schools to teach in Mongolian language (without being detrimental to Mandarin fluency) and for Mongolian cadres to learn and conduct administrative work in Mongolian. During the Socialist Education Campaign (1963–65), Ulaanhuu boldly suggested that all cadres, regardless of ethnicity, working in predominantly Mongolian areas should learn how to speak Mongolian in order to connect with and serve the masses. In a clever application of Maoist logic, Ulaanhuu argued that if the masses speak Mongolian, then so should the cadres. Otherwise, there would be a risk of alienation that would ‘severely impact the relationship between the Party and the people’ (Heqiyeletu 2020).

The commitment to linguistic diversity in the IMAR was also conducted on the cultural front. In 1957, the cultural troupe Ulaan möchir ‘Red Twig’ (乌兰牧骑) was formed with the purpose of travelling to IMAR’s far-flung localities in order entertain, educate, and disseminate propaganda (I am not using this in a pejorative sense) to Mongolian herders. In the 1960s, teams of travelling film projectionists were encouraged to study the local dialect so that they could provide ‘oral translations’ (口头翻译) for local audiences (Lam 2019). In the early Mao years, multilingual acts of nation-building and socialist political education belonged to the same ‘imagined community’ of the People’s Republic and were not viewed as mutually exclusive (Anderson 2016).

In the history of the People’s Republic, it was only during the Cultural Revolution, when ethnic Mongolians were persecuted and over 16,000 murdered on the basis of the paranoid suspicion, which conjured the unexorcised ghosts of revolutionary history, that Mongolians belonged to a separatist, underground Party—the so-called neiren dang (内人党)—that Mongolian language education was terminated (Yang 2014). It goes without saying that Ulaanhuu became a target of struggle in the early years of the Cultural Revolution, although he was politically rehabilitated as early as 1973.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Communist Party sought to ‘restore order’ and ‘rectify the left tendency (左倾) of Great Han Chauvinism’ that left behind tremendous turmoil and trauma in the borderlands. One way of doing that was the promise of increased autonomy and opportunities for language education. For example, Clause 36 of the Regional Autonomy Law promulgated in 1984 grants the right of regional autonomous governments to determine educational policies, including ‘the language of the school’, which should ‘to the extent possible, use textbooks written in the minority language, and the classroom language should also be that of the minority’. Other clauses deal with the distribution of power between the regional autonomous governments and the central government, including autonomy over economic construction and national resource development. Massive student-led protests broke out across the IMAR in 1981 when it seemed that the local officials were reneging on the Party’s commitment to territorial, linguistic, cultural, and economic autonomy (Jankowiak 1988). The shadow of the Cultural Revolution, under which these children grew up, gave them good reason to be anxious over the future.

From Lenin to the ‘Multicultural’ United States?

It may seem puzzling to the outside observer why Inner Mongolians have been protesting—and why there have even been reported suicides—over seemingly minor changes to the model of language education and slight modifications of textbooks. The Chinese state has not banned the use of the Mongolian language, as some have exaggerated.

One way to explain the reaction is that small adjustments can be the harbinger of larger, more seismic changes under way. Are these changes to language education policy ‘surreptitiously implementing’—as Atwood (2020) has suggested—a version of the ‘Second Generation Ethnic Policy’ (第二代民族政策) that has been proposed by Hu Angang (Centre for China Studies, Tsinghua University), Hu Lianhe (an official with the United Front Department, also affiliated with Tsinghua University), and Ma Rong (Peking University), which would indicate a shift from ethnic autonomy to multiculturalism (Hu and Hu 2011; Ma 2019)? As Christopher Atwood (2020) explains, for these thinkers, ‘the Soviet-based ethnic autonomy built into China’s constitutional structure was a mistake and should be replaced by a “depoliticised” ethnic policy modelled on that of the United States, where ethnic groups have individual rights to equality but no rights to territorial autonomy and no state-supported education or cultural maintenance.’ Although it is highly improbable that the Chinese government will abolish autonomous regions, Beijing seems to have embraced the spirit behind their proposals that territorially grounded ethnic autonomy and consciousness stand in the way of the broader vision of the ‘Chinese dream’ (中国梦) and the renewal and ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’ (中华民族伟大复兴), as it oscillates between multiculturalism and assimilation. The right to ‘develop one’s own language’ guaranteed by the Constitution and Regional Autonomy Law that was a key plank of ethnic relations in the Mao and reform eras is being directly challenged by the new bilingual education policy. The changing reality will most likely leave in place the institutional structure and name of the Autonomous Region, while further emptying its content and any remaining meaningful sense of ‘autonomy’.

The potential reason for these transformations can be gleaned from Xi Jinping’s description of the relationship between Chinese ethnic groups as ‘closely united like the seeds of a pomegranate that stick together’ (像石榴籽一样紧紧抱在一起) (Xi 2017)—the American melting pot with Chinese characteristics. The irony here is that China is aspiring to be more like the United States while Trump is taking a page from the CCP playbook and calling for ‘patriotic education’ to douse the flames ignited by the combustible history of the United States’ foundations in slavery and settler colonialism.

What is it about the US multicultural model that these thinkers are drawn to? From their perspective, the problem with China’s system of minzu autonomous regions is that it promotes ‘territorial consciousness’ (领土意识), which is believed to sow the seed of ‘separatism’ (分裂主义). Instead, Ma Rong calls for a dual process of ‘culturalisation’ (文化化) and ‘de-politicisation’ (去政治化) that would reduce minzu autonomy to a deracinated form of ‘culture’—in other words, while cultural difference is to be celebrated, political autonomy is to be eradicated (Sinica 2019). As the anthropologist Bulag (2003, 762) put it over a decade ago, ‘domesticated Mongols can now choose to sing and dance as they please, even speak their language if they care. But they have lost the economic, social, and cultural preconditions, as well as the political powers that can meaningfully define the purpose and quality of their native speech.’ To me, this sounds uncannily similar to Audra Simpson’s (2014) criticism that in North America, the political existence of sovereign indigenous nations is reduced to questions of race (in the United States) and culture (in Canada), erasing the ongoing disputes over territory and political sovereignty. Indigenous protests and uprisings are reminders that indigenous people are ‘not settled, they are not done, they are not gone’ (Simpson 2014, 33).

Blinded by the Light

When it comes to understanding these ongoing indigenous struggles against the infrastructural expansion and carceral policies of North American settler colonial empires, I reach for the work of indigenous thinkers like Audra Simpson, Glen Coulthard, and Nick Estes. So, it has been puzzling to me why Estes—whose work I admire greatly—has recently dismissed criticism of China coming from the left as Orientalist. On 8 August, responding to a Tweet in which the Indigenous Anarchist Federation accused China of settler colonialism, Estes responded: ‘Orientalism is a helluva drug. Just say no.’

Tweets like this are part of a growing tendency on the left to downplay criticism of China based on the fear that it will play into the hands of United States imperialism—or less charitably, because of a faith-like need to believe that China still upholds socialist values. The latter position is epitomised by Vijay Prashad (2020), who at a recent forum of the Progressive International dismissed concerns raised by other leftists over the Chinese Communist Party’s abysmal record of labour repression (in the reform era) as mere contradiction or confabulation (as if with a wave of the hand the discriminatory household registration system, dormitory regime, managerial despotism, and state repression of workers and Maoist student reading groups could just magically vanish into thin air). I, too, value international solidarity and am thoroughly exhausted by how the left cannibalises its own, but as labour sociologist Eli Friedman pointed out on Twitter, this still begs the question: solidarity with whom?

These more difficult discussions, however, are almost immediately drowned out on social media by the endless accusations that criticism of China means support for the United States—and here the stakes of leftist solidarity have deteriorated into a game of identity politics and standpoint epistemology. It does not matter what you say, only where you say it from. Take, for example, the Qiao Collective—whose pro-China positions have been dissected by Brian Hioe (2020)—and their recently published defence of the Chinese state’s bilingual language policy in Inner Mongolia, which takes official claims at face value, while ignoring Mongolian voices, and blames Western media for over-sensationalising the issue. To make their case, Qiao (2020) relies entirely on ‘clarifications offered by local officials as well as a debunking by the Global Times’. I am not saying that official statements and discourse should be ignored; I have always argued the opposite point that they need to be critically examined and contextualised (Sorace 2017). Qiao, however, simply accepts the official line that changes are minimal and a ‘far cry from what Western media has claimed is a “push to wipe out Mongolian culture”’. By blaming Western media, Qiao entirely ignores the collective petitions and voices of Mongolians both within IMAR and the Mongolian diasporic community, who, it is important to note, do not speak in a homogeneous voice despite shared opposition to the policy; Inner Mongolians have carefully petitioned on the basis of law, while many Mongolians in Ulaanbaatar and abroad have tended to engage in more inflammatory rhetoric. Again, this is a textbook example of ignoring the viewpoints of non-Han, marginalised groups by reframing the problem as one of Western imperial arrogance toward China. Almost on cue, Qiao (2020) argues that ‘assuming that the Chinese people are not extensively dialoguing over a longstanding and deeply felt policy such as bilingual education is the height of chauvinism’, without one mention of the importance of indigenous language instruction in combating Great Han chauvinism, and why the changes to it might undermine those very principles. Qiao seems incapable of asking: are Mongolians part of this conversation about the future of their own language?

It is beyond disheartening that the language of anti-imperialism is being deployed in defence of chauvinist attitudes, which, following Lenin, should be fought wherever they appear. In one video on WeChat, a Chinese man justifying the proposed changes shouts into the camera: ‘You are Chinese, why don’t you speak the language of China?’ (你是中国人,为什么你不会说中国话?). Can Qiao or Prashad enlighten me as to what distinguishes this attitude from the American who barks: ‘This is America, speak English’?

And Back to Lenin’s Anti-imperialism

I wholeheartedly agree that we need to oppose the anti-China consensus, narrative, and war machine in the United States. For these reasons, I am against petitions to the United States government—especially those addressed to the current President—to act on behalf of people oppressed by the Chinese state. Anyone who turns to Donald Trump as a ‘saviour’, even symbolically or in desperation, is undermining the struggles against ascendant fascism and white supremacy in the United States. It allows US political elites—many of whom were responsible for the war crimes of invading Afghanistan and Iraq—to maintain the delusion that the United States is a beacon of freedom and democracy. Furthermore, as comrades in the Lausan Collective (2019; also see Chan 2020) have demonstrated, US grandstanding against China’s actions in Hong Kong not only has been ineffective, but worse, has entirely backfired. To anyone naïve enough to still believe that US politicians care about them beyond their instrumental value to stick China in the eye, I recite the Chinese saying: ‘When the hare is dead, cook the hunting dog’ (兔死狗烹).

Perhaps I am being overly cynical, but I would venture that neither the vocal pro-China left nor anti-China hawks actually give a damn about what is happening in Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, or elsewhere. The latter look for any ammunition they can find and fire indiscriminately, while the former grasp for anything that they can use as a shield to deflect criticism. Most ‘discourse’ that falls into the binary of being either for or against China is nothing more than the enjoyment of short-lived attention and moral outrage. In the end, we are all stupider.

In opposing the rhetoric of Sinophobia in the United States and any corresponding military action, we must not forgo shared leftist commitments to end the oppression of indigenous peoples, the exploitation of the working class, and destruction of the environment that take place in China. The choice we are facing is not China versus the United States, but international proletarian solidarity or ethno-nationalist capitalism.

That is why it is important to remember, and salvage, the Leninist opposition to great power chauvinism at the forgotten origins of the language policy. To my knowledge, this point has only been articulated by the ‘Cherry Society’ (樱桃社)—a Marxist-Leninist reading group formed during the pandemic—who argues that the new language education policy sacrifices Marxist-Leninist principles to a ‘Han imperialist dream’ (大汉帝国梦). Their proposed slogan ‘long live class solidarity of the working people of all ethnicities’ (各民族劳动人民的阶级团结万岁) should resonate beyond the Chinese context.

As China deracinates its remaining Leninist roots, it is only ‘communist’ in the imaginations of people who need it to be so for their own political ends. This not only blunts any analytic capacity to understand what is happening in China, but it also enervates our collective imagination of what a communist future might look like.

The author would like to thank Christopher Atwood for commenting on earlier drafts of this essay.

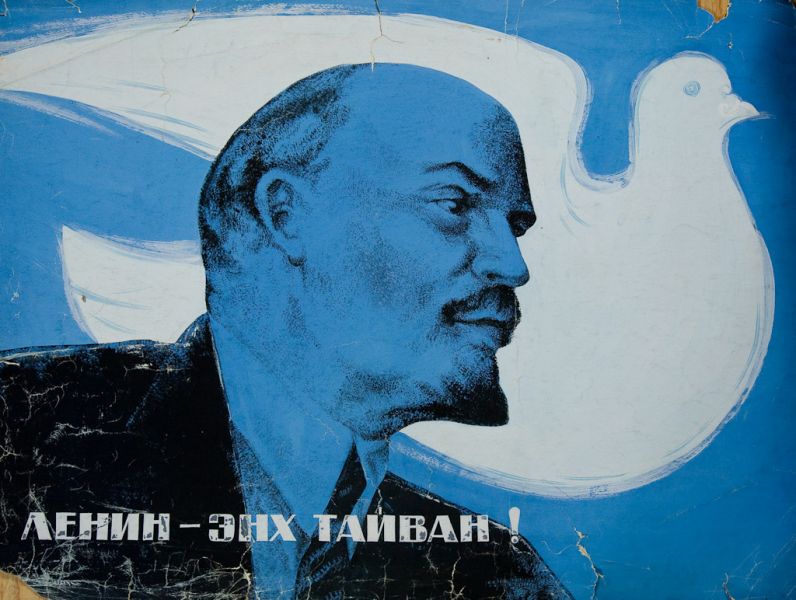

Photo Credit: Ts. Davaahuu ‘Lenin-Peace!’ Courtesy of Mongolian National Modern Art Gallery.

References: