A Brief History of Pakistan–China Legal Relations

One of the meta questions in the study of contemporary China is whether the Government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is building its own international legal order. Some experts argue China is causing a turn to ‘authoritarian international law’ (Ginsburg 2020). Others, however, contend that while China is introducing change to the international legal order, it is mainly doing so within preexisting frameworks—namely, those of multilateralism, which may limit the nature of that change (Alter, forthcoming). The question about China and the international legal order is particularly regnant at the intersection of law and the study of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), where scholars view a ‘big bang’ Chinese approach to international law through an explosion of soft-law agreements and memorandums of understanding between member states coupled with China’s promotion of its international commercial arbitration, the training of judges on cross-border dispute issues, and even construction of bespoke courts to take on international disputes. Yet, like much BRI scholarship, observations may illustrate the problem of presentism that can elide the deeper histories of the PRC and what used to be called the ‘Third World’ and is, more currently, known as the ‘Global South’, including their legal dimensions.

The question of the archaeology of the BRI as proposed by this issue of the Made in China Journal is an important one, especially when one considers talk of a ‘new Cold War’ between the United States and China, recalling that small dependent states, in particular, were once the specific theatres for the drawn-out competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War analogy is potentially forced—the contemporary stage of global economic interdependence may prevent complete decoupling despite de-listings and tariffs—but the perspective of small states is a helpful starting point in contemplating the PRC’s longer histories of involvement in such states, and how such histories may shape contemporary legal orders. This brief essay uses the history of Pakistan–China legal relations as a window on to ‘international law as hedging’ (Nguyen 2020), to unearth some of the strata below the surface of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)—the feature that today attracts most attention concerning the two countries’ relations. A short legal history of bilateral relations demonstrates how Pakistan, like many small states, may gravitate towards powerful capital-exporting countries, such as China, as epicentres of international law orders, yet remain a participant in other, overlapping orders to mitigate overdependence and increase optionality. This insight may help us understand more clearly the broader picture of multiple and competing international legal orders.

The Establishment of Diplomatic Ties

On 20 May 2021, Li Keqiang, Premier of the PRC, telephoned Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Imran Khan, on the eve of the seventieth anniversary of the founding of diplomatic relations between the PRC and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (Embassy of the PRC in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 2021). The two sides pledged to work together to fight the COVID-19 pandemic as part of their ‘all-weather strategic partnership’ (全天候战略合作伙伴关系)—a catch-all expression coined in the late 1970s that has since come to define the Pakistan–China relationship. Experts agree that, along with North Korea, this is one of the PRC’s most enduring relationships, which has weathered periodic ups and downs (Garver 2016: 736). The reasons for this endurance are manifold, including, centrally, the geostrategic position of Pakistan as India’s neighbour and rival, but also commercial factors such as investment and trade, and concerns about national security and terrorism. International law has been one ingredient of this enduring relationship.

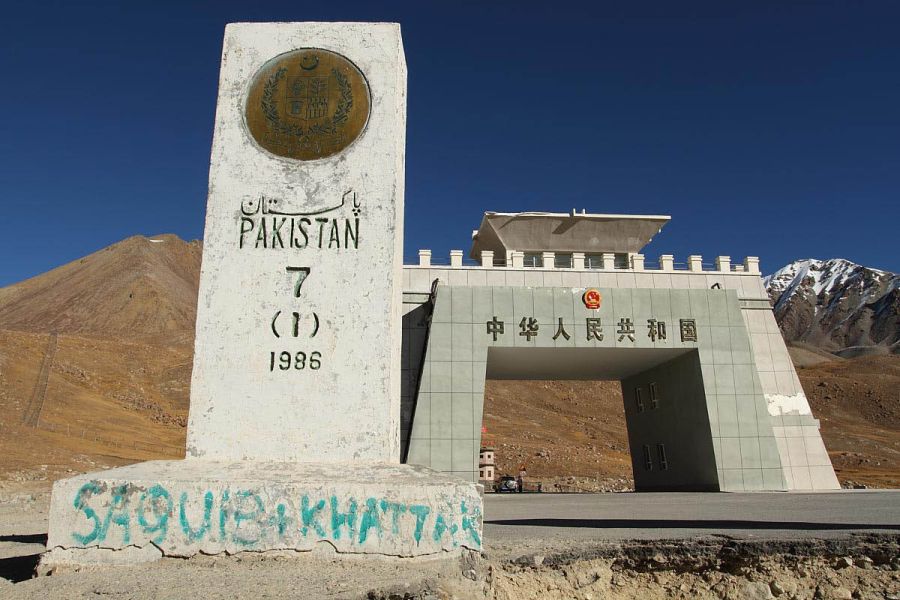

Despite contemporary political oratory concerning the ancient friendship between Pakistan and China—allegedly hearkening back to the historic Silk Road of the Tang Dynasty—the relationship as understood today is largely a modern creation. Both Pakistan and the PRC were formed by contemporaneous violent movements, including decolonisation and civil war. The concurrence of the emergence of the modern state in both cases seemed to initiate mutual recognition. In 1947, when Pakistan was still a dominion and China was governed by the Nationalists of the Guomindang (GMD), Pakistan established a consulate in Kashgar, China’s westernmost city (Wang 1981: 4). Chiang Kai-shek, then leader of the GMD and the Republic of China, did not, however, support Partition of the Indian Subcontinent. On the defeat of the Nationalists and the victory of the Chinese Communist Party, India recognised the newly founded PRC, on 30 December 1949, and Pakistan followed a week later, on 6 January 1950—the first Muslim state and third non-communist state to do so (Ghulam 2017: 10–12).

The two countries officially established diplomatic relations on 21 May 1951. This implicit recognition of the other’s sovereignty was not just a policy decision but also an affirmation of international law (see, for example, Lauterpacht 1944: 386). It is through state recognition that the rights of states attach under international law. Thus, while not to be overstated, even at the genesis of relations between them, the two states—which have traditionally been seen as outliers in the international legal system—recognised core principles of public international law in relation to each other. As such, the building blocks of the Pakistan–China relationship are consistent with international law—the rules that govern interstate relations—and the two countries would build on this foundation, mainly through bilateral treaties but also through multilateral agreements.

The Cold War

Recognition and use of the principles of international law do not equate to political unity within that system, however, and the Cold War demonstrated how treaty alliances could be the means to Balkanise that system, including occasionally putting Pakistan and China in opposing blocs. Divergence was highlighted by the states’ behaviour in the United Nations. Whereas Pakistan had previously supported the PRC’s efforts to replace the Republic of China in the United Nations, by 1953, Pakistan began voting with the United States against the PRC’s UN seat—commensurate with increasing Pakistani reliance on US aid (Syed 1974: 54). Eventually, Pakistan would enter into four defence pacts with the United States and its allies, including some that were anti-Chinese (Ghulam 2017: 19).

One of these, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), was criticised by the PRC on legal grounds. Specifically, the PRC Government argued that SEATO failed to meet the requirements for a regional organisation within the meaning of the UN Charter (Articles 51–54), and did not conform to the requirements in the Treaty of Bandung (Syed 1974: 55). Specifically, the Chinese Government claimed that the United States was using SEATO to sow discord in East Asia and to ring-fence the PRC (Syed 1974: 55). In this sense, SEATO is perhaps one of the first examples of the Chinese Government using a ‘lawfare’ argument against the United States (see Cai 2019). The 1962 Sino-Indian War, however, forced a wedge between the United States and Pakistan, as the former increasingly allied itself with India (Chaudhuri 2018: 42). Subsequently, Pakistan and China increasingly sought to support each other; in exchange for Chinese loans and China’s pro-Pakistan stance on Kashmir, Pakistan backed China’s nuclearisation and maintained silence on its treatment of Uyghurs (Boni 2020).

Cross-Border Trade and Investment

From the late 1960s through the 1970s, Pakistan and China’s relationship became tighter through growing yet still moderate economic activity, although Pakistan also sought aid from the United States and its allies. The Sino-Pakistani entente began in 1964 and saw the countries moving in parallel on policy matters ranging from Taiwan to India. In 1966, Pakistan and China signed an agreement for the sale of military hardware totalling US$120 million, as China became one of Pakistan’s main suppliers for such equipment—a supply that, remarkably, continued unabated even during the ‘10 years of calamity’ of the Cultural Revolution (Ghulam 2017: 61).

Following a brief US–China–Pakistan pact to contest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Pakistan continued to draw on aid from both China and the United States and its allies. The specific legal form of Chinese aid to Pakistan changed during the late 1970s from grants to loans (Ghulam 2017: 100). Consequently, commercial elements entered the relationship, although a non-commercial logic still undergirded many of these loans. Loans nonetheless enabled nascent cooperation in the fields of agriculture, energy, and industry.

In parallel, the two countries entered standard economic treaties. On 12 February 1989, for instance, the two countries signed a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) (‘Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan on the Reciprocal Encouragement and Protection of Investments’). The BIT contains standard clauses including investment in accordance with local law (Art. 2), equitable treatment and most-favoured-nation clauses (Art. 3), expropriation (Art. 4), and tiered dispute settlement through diplomatic channels and ad hoc arbitration (Art. 9). Significantly, the BIT, which remains in force today, does not contain the standard language of more modern BITs, such as the right to regulate, sustainable development, and social investment, suggesting that despite the entente, the two countries have not been able to procure the political will to update and amend the BIT—a problem seen in many of China’s other outdated BITs.

Security and Anti-Terrorism

Pakistan has become a major client of both the United States and China for the purchase of military equipment, generating relationships that typify the country’s hedging strategy. In the wake of 9/11, Pakistan became an indispensable ally in the US Global War on Terror. In June 2004, US President George W. Bush designated Pakistan a ‘major non-NATO ally’ and, two years later, signed arms transfer agreements with Pakistan worth more than US$3.5 billion, making Pakistan first among all arms clients of the United States that year (Grimmett 2009: 1–2). The United States has not signed the Arms Trade Treaty, which came into force on 24 December 2014, meaning its arms sales are not governed by that international agreement.

The Chinese Government has built up Pakistan’s military capability mainly to check India, but its arms sales are also part of an ongoing negotiation regarding the PRC’s concerns about Xinjiang. From 1993 to 1997, Pakistan bought 51 per cent of all the PRC’s arms exports, effectively building the modern Pakistani war machine (Garver 2016: 739). Interestingly, China did sign and ratify the Arms Trade Treaty, on 20 June 2020, which will require the compliance of its domestic laws on arms export, as well as mandate reporting requirements.

Currently, China also spearheads an alternative framework for regional security and source of international law in the form of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which is often cited as a key example of a China-led ‘authoritarian international law’ (Ginsburg 2020: 247). The SCO has been viewed, in particular, as the externalisation of China’s Strike Hard campaign against terrorists in Xinjiang (Small 2015: 76). In 2017, both Pakistan and India joined the SCO. Although there is no direct clash, it remains to be seen how Pakistan will balance its duties as a member state of the SCO with its obligations under the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF), a body organised by the G-7 to combat money-laundering for the financing of terrorism. The withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan in August 2021 and the quickly evolving events in that country may put some of Pakistan’s legal obligations to the test.

A Legal History of Superimposed or Buckling Layers?

While geopolitics remains integral to Pakistani–Chinese relations, and economic ties have grown over time, law is also one source of norms in the relationship—and one that may undergird the foregoing. Pakistan–China relations show a layering of multiple sources of international law: mutual assistance treaties, investment treaties and sundry private contracts, free-trade agreements, soft loans, concessional financing and other forms of lending, and industrial, agricultural, and military agreements. Collectively, these sources of law form a latticework of legal norms and obligations between the two countries. At the same time, this latticework intermeshes with other legal arrangements that Pakistan has sought with other powers, including the United States.

Consistent with the notion that smaller states ‘hedge’ international law (Nguyen 2020), Pakistan continues to seek to embrace pluralist notions of international law to optimise its material and other benefits. A question remains, however, about whether different orders of international law are harmonious in terms of the obligations they impose on members, particularly smaller states. Pakistan benefits from these competing arrangements, but it may also be constrained by them. Anyone in the legal industry in Pakistan is familiar with the infamous 2019 Reko Diq case, in which the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes awarded an Australian mining company damages worth US$5.84 billion against the Pakistani Government. The case revealed some of the country’s shortcomings in meeting its obligations under an existing bilateral investment treaty with Australia. Pakistan’s agreements with China under CPEC and its commitments to the International Monetary Fund’s Extended Fund Facility are just the most recent strata lying atop a thicker stratigraphy of such legal relations. This cursory overview suggests that while there may be different values towards and interpretations of international law underpinning the established order and the Chinese alternative (for instance, regarding the presence of conditionalities in lending, the role of national security in development, the relationship between business and human rights, etc.), in some ways, the relationship between the two is less antagonistic than additive. Layers upon layers. All of this will keep Pakistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and related offices that track the country’s commitments under international law, quite busy.