From Grassroots Nostalgia to Official Memory: Red Relics in Contemporary China

The year 2021 marked the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—an occasion that was celebrated with events throughout the People’s Republic of China (PRC). These initiatives foregrounded the role of the CCP in China’s rejuvenation and coincided with a campaign within the Party to encourage the study of Party history with the aim of promoting the ‘correct line’ of history, as made clear by the publication of the new ‘Brief History of the Chinese Communist Party and the ‘Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party’ in late 2021. This focus on history has come in the larger context of President Xi Jinping’s leadership, which, according to Mike Gow (2021: 81), has emphasised the CCP’s ‘moral and ideological leadership’ as key pillars of their ruling legitimacy.

This essay investigates the relationship between historical objects and the memories that are constructed around and through them and explores the ways in which outside forces can influence this link. In particular, I examine the changing role of ‘Red relics’ (红色文物) in this ‘return to history’ by looking at a media campaign in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, that asked schoolchildren to find so-called ‘Red treasures’ (红色宝贝) in their homes and tell their ‘Red stories’ (红色故事). I begin by tracing earlier engagements with these objects in the form of collecting, a pursuit that first emerged in the early reform era and which reflected a form of nostalgia for the Mao Zedong years. In focusing on the changing role of these relics, I contrast this previous ‘grassroots nostalgia’ that used the past to criticise the present, with the contemporary ‘state-constructed nostalgia’ that conversely uses the past to legitimise the present. In so doing, I consider the ways in which memories are mediated through engagement with objects and the ways in which different social actors use objects as the embodiment of values in radically different ways.

From Grassroots Nostalgia to Official Memory

The term ‘Red relic’ refers to objects made between 1921 and 1978 that have some connection with the CCP, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the PRC, or its top leaders (particularly Mao), either aesthetically or politically. It most frequently refers to objects like Chairman Mao badges and propaganda posters, and is often associated primarily with post-1949 objects, but as I discuss in this essay, in recent years, collectors in China have given pieces from the pre-1949 period increasing prominence, in part due to their impeccable revolutionary heritage and their association with a less politically sensitive period of CCP history. Collections began to be formed in the late 1980s, before becoming more prominent and mainstream in the 2000s, and over time, the field has changed considerably.

Most English-language academic literature on early ‘Red collecting’ has understood it as reflecting nostalgia for the Mao era (Bishop 1996; Dutton 1998; Hubbert 2006). There is often a tendency in the literature on nostalgia more broadly to see it as a malady, as delusional, and as reflecting a desire to return to an idealised past that never existed (Boym 2001). This perception governed early writing about post-communist nostalgia in the former Soviet Union (Todorova 2010), but now also applies to analyses of the nostalgia-powered political movements in Western countries in recent years. It is more helpful, however, to regard it not as mindless longing, and certainly not as an uncritical desire to return to the past, but, as Frances Pine (2002: 111) writes, as ‘an invocation of the past … to contrast it with, and thereby criticize, the present’.

The comparative power of nostalgia is evident in the writings of Red collectors themselves. Beijing collector Qin Jie (2008: 12) explicitly positions popular and nostalgic remembrances around the time of the ‘Mao fever’ in 1993 as centred on cherishing the memory of Mao, but also points out this was powered by the ‘emotional remembrance of the fairness and justice of the revolutionary era … against the background of the widening gap between rich and poor’ (in this context, the reference to ‘revolutionary era’ likely refers both to the pre-1949 period and to the Mao years themselves). He draws a contrast between the perceived equality of the Mao years and the inequality and corruption of the reform era, and links this not only to nostalgia for Mao, but also to interest in collecting. He writes that ‘[f]or many people, red collectibles is [sic] collecting their own soul, youth and enthusiasm’ (Qin 2008: 12), thereby highlighting the role that Maoist ethics played in many collectors’ youth and tying this system of ethics to the material culture of the era.

Yet, we can also understand these laments in another way: they are not just about missing the past, but also about a future that the CCP had promised to these people in their youth. Roxanne Panchasi (2009) argues in her book on interwar France that differing visions of ‘the future’ contributed to different eventual forms of remembrance and commemoration. Panchasi’s work highlights that nostalgia, while seemingly past-oriented, is also about visions of the future. Socialism, as with many ideologies, is in many ways fundamentally future-oriented: China in the Mao era may have been poor and ‘backward’, but socialism held the potential of a future China that was prosperous and equal. Indeed, this is one interpretation of the art of the era: the posters and paintings represented not the China of the day, but the China of the future—a China remade under socialism (Tang 2015). What post-Mao nostalgia represents is thus not the loss of the existing conditions of the Mao era, but the loss of the promised future. It is a harking back to the past, not for the sake of the past itself, but to retrieve a vision of the future different from that which emerged.

Red collectors, most of whom were young people in the Mao era, were raised in the spirit of optimism for the future, only to be confronted with the uncertainty of the reform era, with its new social order driven by values at odds with those of their childhood. One Shanghai collector, for example, who came from a revolutionary family and was first a Red Guard and then a sent-down youth during the Cultural Revolution, spoke about his disappointment in the direction China had taken in the reform era:

Corruption in China really is the most serious problem. The whole society has broken down … I look at the portrait of Chairman Mao: it represents fighting for socialist construction. I look at it and it brings you to tears that such a good system, a moral system, a socialist system, has been affected by capitalism. (Interview, October 2017)

For this collector, the Red relic he looks on represents not the conditions of his youth, but rather the spirit of the time during which they were fighting for a socialist future. This fight has now been, in the collector’s eyes, abandoned in China’s pursuit of wealth and power.

The grassroots nostalgia that is evident in the quote above certainly played a role in Red collecting, particularly in its early stages in the 1980s and 1990s. However, it has become a more marginalised aspect of the field in recent years, as over the course of the 2000s, Red collecting has become more professionalised and legitimised as part of mainstream collecting. The Party-State has recognised many types of Red relics as cultural relics, and the major collecting associations now all have government approval through the Ministry of Culture.

While many collectors still express their belief in the moral legitimacy of the objects, this is increasingly framed not as a criticism of the CCP’s path in reform-era China, but rather, at least publicly, as a vindication of the CCP’s ‘correct’ historical path. Hebei collector Niu Shuangyue, who is prominent in one of the two national collecting associations, argues that Red culture and relics are the ‘spirit and the soul’ of the CCP, which has led the Chinese people from ‘victory to revival’ (Personal communication with Niu, June 2018). There has been a shift in the public discourse on Red collecting to frame these objects not as reminders of past ideological correctness (to be contrasted with present lapses), but as patriotic symbols of the hardship of the past that led to present happiness. Fujian collector Hong Rongchang, for example, sees a link between the struggles of the revolutionary predecessors, the correct policy of Reform and Opening Up, and present prosperity (Wang 2015). For Hong, today’s happy and prosperous life reflects the fulfilment of the dreams of the revolutionary era, which were only possible because the CCP was victorious in the fight for state power, which it truly realised after 1978. Engagements with Red relics represent, then, not just different understandings of the past, but also different understandings of what future that past promised.

These new understandings more closely resemble what we can view as ‘official memory’ in China and have become more common in the field of Red collecting in recent years. This has been matched by the growing prominence collectors have given to pre-1949 objects, which we can understand in the context of the renewed focus on Party history under Xi Jinping. This has led to an increased focus among both scholars and collectors on the Party’s historical role in the rejuvenation of the nation, while brushing over historical tragedies such as the Cultural Revolution ever more swiftly than before. Red collectors take seriously Xi’s call to ‘pass on the Red gene’ (把红色基因传承好) and believe their ownership of Red relics leaves them uniquely placed to educate the next generation in the spirit of determination, perseverance, and, of course, acquiescence to Party authority that won the CCP the revolution in the first place. Collecting association publications are keen to position themselves within the mainstream as patriotic members of the cultural elite, whose selfless devotion to their objects has preserved historical relics for the betterment of the nation. As such, while many collectors still hold the views that I characterised as ‘grassroots nostalgia’, there is no doubt that public representations of the Red collecting world have been shorn of these critical associations.

Constructing Red Memories

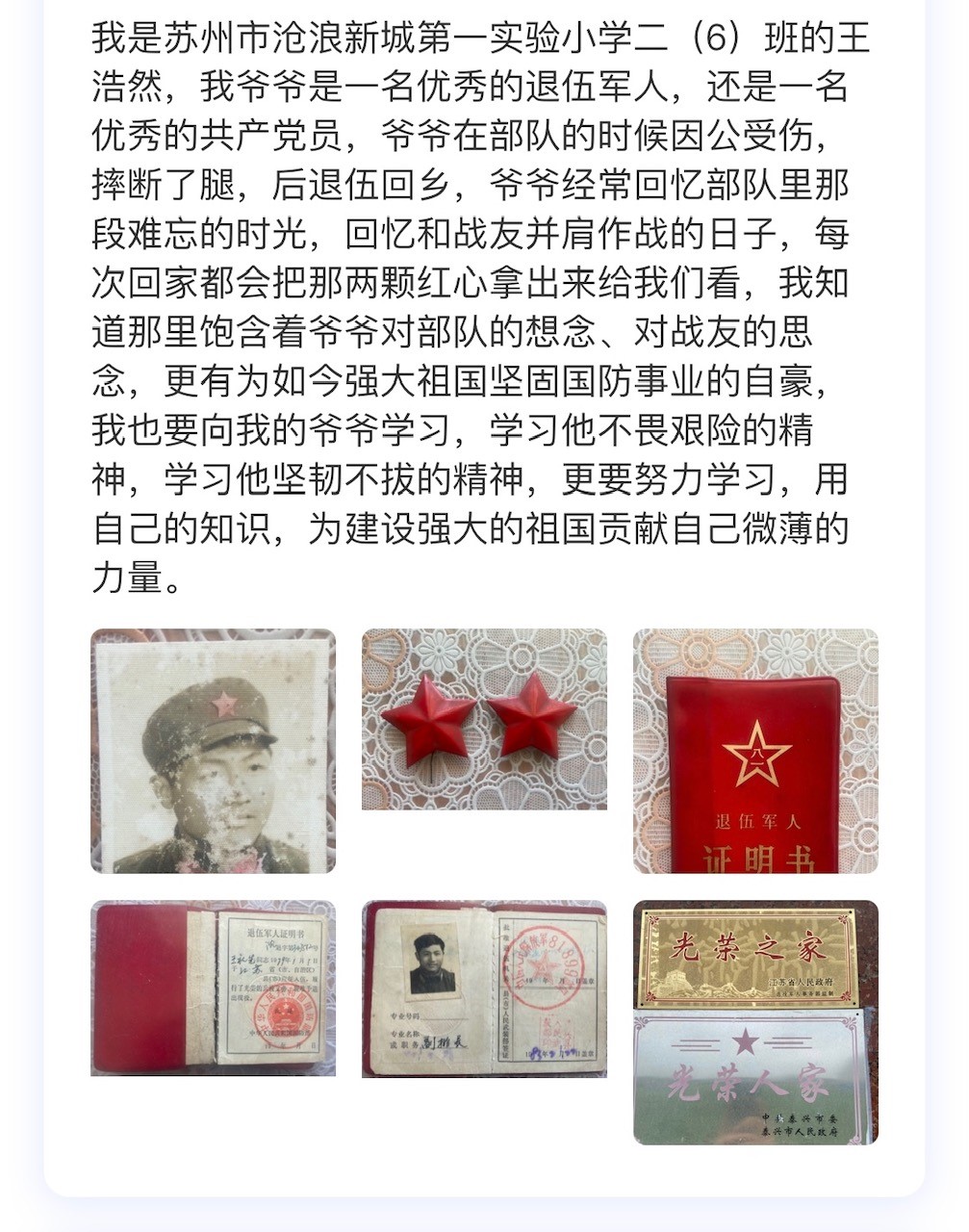

The value of Red relics as a way of backing up official narratives has been recognised not solely by Red collecting associations; rather, as this essay examines, a 2021 moral education campaign launched by the Suzhou Municipal Education Bureau invited schoolchildren to ‘search for Red treasures’ (寻访身边的‘红色宝贝’) in their homes and use them to tell ‘Red stories’ (Suzhou Municipal Education Bureau 2021). The campaign ran from April to July and resulted in a WeChat account that received thousands of pictures from schoolchildren, as well as at least 15 features on Suzhou News (苏州新闻) that were also shared online on Weibo and other social media platforms. The campaign itself did not limit the period of acceptable objects, with the official announcement stating only that these could include ‘military medals, commemorative medals, old objects, old photos, letters, videos, and recordings, among others’. The Red treasure must have ‘Red stories and Party history stories’, but, while a Chairman Mao badge from the Cultural Revolution could fit this description perfectly well, the schoolchildren (or their parents) understood this was not what the campaign was soliciting. The majority of entries submitted on WeChat were from either World War II or the Chinese Civil War. In other words, these items were primarily from the pre-1949 period, with a small number of Korean War medals.

The promotional material for the campaign is clear about the relationship the initiative is trying to establish between these objects, their original owners, the Party, and the schoolchildren:

These ‘Red treasures’

It’s the Party leading the people to work hard

The testimony of continuous development

It’s the children studying Party history

An important vehicle for drawing strength

To further create an atmosphere for studying Party history.

(Greet the Spring Middle School 2021)

The value of the objects is clear: they represent the Party’s wisdom in leading the people and the children studying the objects today. A network is constructed between the object, family history, the Party, and the individual child, driven by the Party’s attempt to construct an explicit relationship between them. One can understand the campaign as the Party’s attempt to create a ‘constructed nostalgia’ in which the CCP establishes an emotional link between the younger generation and their revolutionary forebears through the practice of telling the object’s Red story.

As mentioned above, the main publicity for the campaign were several professionally made short films released on Suzhou News and Weibo. All the films share a similar pattern: they begin with the children looking at the ‘Red treasure’ with admiration before hearing the object’s ‘Red story’ from their family member, which is brought to life with historical film footage and photographs. The videos end with the children expressing what the object means to them and what they can learn from knowing its Red story. For example, one story featured by Suzhou News shows a young girl visiting her great-grandmother (aged 100) in the hospital. The girl tenderly pins a medal from the Korean War to her elderly relative’s chest, and they look at a photo of the great-grandmother as a young woman. The woman joined the army as a teenager against her family’s wishes and became a frontline nurse. The old woman’s memories, the voiceover muses, are ever blurrier, but the objects remain a testament to a time that was hard yet full of hope. It suggests that even after the woman passes away, the memories will not be lost because they have been passed down already to her grandchild through the Red story of the object itself. The story clearly has the desired effect on the child, who speaks of her pride in her grandmother when she hears her story (Suzhou News 2021b).

In another story featured on Suzhou News, the individual memory-holder is replaced altogether with the object. A young boy presents his great-great-grandfather’s martyr’s certificate. His great-great-grandfather had joined the CCP as a university student and was in the Eighth Route Army, but he and his wife were killed by the Japanese, orphaning their children. The boy reads out a letter he has written to his great-great-grandfather, saying that while he never met him and did not even have any photos of him, hearing his grandfather tell his story made him realise that this long-deceased relative was the family’s greatest hero. The object has replaced the individual as the recipient of the boy’s attention, but it is framed as embodying the spirit of the forefather. The boy concludes that now life is so good, everybody must study well, thus making clear the relationship between his ancestor’s sacrifice and his own good fortune—all mediated by the Party.

In this story, an emotional link is formed between this boy and his long-deceased relative, facilitated by the martyr’s certificate and the story he has learned from his grandfather. In their own telling of their family stories, the schoolchildren then come to embody the family’s experience of revolution, in which greatness comes from proximity to the Party and is given material form in the historical object. Although calls to pass on the so-called Red gene are often vague, this campaign represents the CCP’s attempt to transfer the mantel of Red inheritor to children through their encounters with Red relics (Suzhou News 2021a).

Other news stories also demonstrate the ways in which the campaign was accessible to those whose family lacked Red treasures. Some schools organised events in a ‘show-and-tell’ style in which the aged owners of objects came into the schools, recounted their stories, and passed around the objects for all to see. On show, then, are the object and the person, and through the telling of the Red story, each child has a chance to come into contact with Red history.

Red Treasures as Patriotic Education

We can see this initiative as a type of patriotic education campaign—variations of which have been common since at least the early 1990s. While we may think of patriotic education as dull Party history lessons in schools, it is increasingly sophisticated and aims to inculcate the correct values and understandings of history through lived experience (Gow 2021). In tracing the different associations with Red relics, we can see, then, a clear transformation from the grassroots nostalgia of the 1980s and 1990s, in which collectors used objects of the past to criticise the present and to lament the loss of a promised future, to the contemporary uses of Red relics, such as in the Suzhou Red Treasures campaign, which aim to construct nostalgic memories of the revolutionary era in the younger generation. This campaign uses objects of the past to legitimise the present and sees in the present the fulfilment of the promise of the revolution. Memory is by nature plural and incomplete; it operates in ways at once official and social, collective and individual; it leapfrogs over time periods, entrenching some moments with great significance while excluding others; it pieces together meaning in ways that are typically more about the needs of the present than the past. Historical objects share these tensions, as they can embody both official memory and other kinds of remembrances. As this essay has shown, Red relics have been and continue to be associated with a variety of historical and ideological perspectives, ranging from a grassroots nostalgia in the 1980s and 1990s, to something much closer to official memory today.