Ambivalent Nostalgia: Commemorating Zhiqing in the Jianchuan Museum Complex

Since the 1990s, China has been host to pervasive displays of ‘zhiqing nostalgia’ by the former ‘sent-down youths’ or ‘educated youths’ (知青 zhiqing, an abbreviation of 知识青年). Born in the 1940s and 1950s, this generation participated in the ‘Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside’ movement (上山下乡), which started in the mid 1950s but gained traction only during the Cultural Revolution (Yang 2003; Bonnin 2013). In those years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sent millions of urban educated youths to be ‘reeducated’ on collectivised farms in remote towns and villages. Once there, zhiqing often endured hunger, intensive labour, and other difficulties. Many eventually had families in the villages and stayed, while others returned to the cities when the movement ended in the early 1980s.

Michel Bonnin (2016: 756) describes the zhiqing as a ‘lost generation’, deprived of ‘their youthful illusions and the pure idealism on which they were raised as children’ and of ‘the opportunity to study’. However, in contrast with Bonnin’s argument, being ‘sent down’ did not prevent some in this group from afterwards becoming well-known politicians, entrepreneurs, artists, and intellectuals in the reform era. Because of their urban and often elite backgrounds, the sent-down youth had the social and intellectual resources to write about and publish their experiences during the Cultural Revolution. These writings made zhiqing ‘probably the most active group in the realm of collective memory in Chinese society today’ (Bonnin 2016: 756). Indeed, in comparison with the ‘Red Guards’ (红卫兵), who were, like zhiqing, ‘Chairman Mao’s Children’ (Chan 1985, cited in Xu 2021), memories of the zhiqing appear less politically ‘difficult’ and their commemoration is better tolerated by the Party-State, though ‘it would be incorrect to assume that the memory of the rustication experience was not, and is not, restricted by the authorities’, as Bonnin notes (2016: 756).

Considering this, the zhiqing movement has been probably the most actively remembered and well-documented episode of the Cultural Revolution, both by these former sent-down youths and by the CCP itself. In the late 1970s, ‘scar literature’ (伤痕文学) began to voice mournful and critical reflections on the rural experiences of the zhiqing, and particularly the elements of personal deprivation, fatigue, poverty, and suffering. This was followed by a wide range of writings, mostly by members of the zhiqing generation, including autobiographical accounts, collected essays, memoirs, and academic studies of zhiqing history.

These accounts have articulated diverse and sometimes contradictory narratives and attitudes—from the idea of being scarred/wounded and laments for wasted talent and youth, to expressions of nostalgia and claims of pride in zhiqing identity. This has resulted in a divisiveness and ambivalence in the expressed narratives regarding how zhiqing history should be told today. This essay investigates these competing discourses from the vantage point of the Jianchuan Museum Complex (JMC), one of China’s most high-profile private museums.

The Zhiqing Generation in Museum Commemoration

Museum commemoration of the zhiqing generation began in 1990—the year the Museum of Chinese Revolution in Beijing staged the first exhibition organised by a group of former zhiqing under the title Souls Tied to the Black Soil (魂系黑土地). These educated youths had been dispatched to Heilongjiang Province, on the border with Russia, and by then had become government officials in Beijing (Xu 2021). The exhibition was a seminal event that attracted more than 150,000 visitors during its two-week run. Other former ‘educated youths’ with official backgrounds organised further exhibitions in subsequent years, including History Testifies to Ordinary Life: A Retrospective Look at Educated Youth on the Military Farms in Hainan and Haibei (in 1991); Regretless Youth: A Twentieth-Anniversary Retrospective Exhibit on the Life of Youth Sent from Sichuan to Yunnan in Chengdu (1991); and Spring Flowers, Autumn Harvests: A Commemorative Exhibit of the Sent-Down Youth in Nanjing (1993) (Yang 2003: 268). As these titles suggest, these exhibitions recognised and embraced the zhiqing identity, along with a proud identification with the collective experience of the movement, thus giving rise to a wave of nostalgia in Chinese society.

In 2002, 50-year-old Chen Shuxin was appointed to build a museum in the historical Aihui District of Heihe, China’s northernmost city, of which he was then vice-mayor. Chen spent six years setting up the country’s first museum about the zhiqing generation, the Heihe Zhiqing Museum. On its opening day in August 2009, the museum in this small city on the border with Russia attracted more than 5,000 visitors.

A zhiqing himself, Chen felt strongly about the importance of remembering and honouring that generation. ‘Many of us zhiqing had our feelings hurt,’ he said in an interview, ‘having devoted our best years to the frontier villages and changed the local isolated environment, we need at least some sort of recognition’ (Southern Metropolis Weekly 2013). The moment the opportunity presented itself, Chen prioritised highlighting the contribution made to China and the positive values represented by the sent-down youth. He thus made patriotic red the dominant hue of the museum. As for suffering and loss, Chen said the museum ‘does not have to tell everything just because they [suffering and loss] happened. History is not a running account’ (Southern Metropolis Weekly 2013).

The Heihe museum was soon followed by an array of similar museums and exhibitions across the country—notably, in Shanghai and in the provinces of Zhejiang, Fujian, and Sichuan. A particularly memorable exhibition was organised by the Heihe Zhiqing Museum and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) on 1 July 2015. This RMB30-million exhibition, entitled Sharing a Common Destiny of the Republic (与共和国同命运), was held at the National Stadium in Beijing. The wave of commemorations highlights the positive elements of the rustication movement and extols the ‘zhiqing spirit’ (知青精神)—a term coined by National Stadium exhibition curator Pan Zhonglin. Pan characterised this spirit as synonymous with qualities of perseverance, self-sacrifice, and patriotism.

As Yang Guobin (2003: 268) has pointed out, these museums and exhibitions denoted a significant shift in the way the zhiqing movement was commemorated in the 1980s. Yang (2003: 269) argues:

[T]his nostalgia emerged as a form of cultural resistance. At its centre was a concern for meaning and identity newly problematised by changing conditions of Chinese life. Nostalgia can help to maintain and construct identities by connecting the present to the past, by articulating past experiences and their meanings, and by directing moral critiques at the present.

From feeling ‘scarred’ to being nostalgic, the shift in attitudes of former zhiqing towards their memories reflects deeper changes in their moral disposition and social life. In a period of profound socioeconomic transformation, the expression of nostalgia—for a past idealised as an age of fairness, sacrifice, and solidarity—thus became a way for some former zhiqing to deal with a crisis of identity when faced with new social problems brought on by the country’s expanding market economy, such as unemployment, economic inequality, and cultures of materialism and consumerism.

A Different Approach

In this context, the Jianchuan Museum Complex (JMC) presents a rather distinctive approach to zhiqing memories, differing from previous, mostly government-backed, attempts to commemorate this period of Chinese history.

In development since 2003, the museum contains the personal collection of self-made multimillionaire and collector Fan Jianchuan. Over the past three decades, Fan has amassed more than eight million items. The JMC is thus a vast compound comprising more than 30 individual museums organised around four themes: the War of Resistance against Japan (1931–45), the ‘Red Age’ (1949–76), the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, and Chinese folk culture. Each topic fits the JMC’s motto: ‘To collect wars for peace, lessons for future, disasters for safety, and folklore for cultural continuity.’

The fifth museum dedicated the Red Age, the Museum of Zhiqing Lives (知青生活馆, hereinafter the Zhiqing Museum), opened in 2011. Fan was a zhiqing from the age of 18, spending three years in a poor village near his hometown in Yibin, Sichuan. On 5 December 2011, as part of the grand opening, Fan unveiled a memorial commemorating 10 female zhiqing from Chengdu who died in a fire in Yunnan on 24 March 1971. The monument, which Fan placed right in front of the museum’s entrance, entitled Pink Remains (粉焚), features 10 gravestones with a display of the women’s zhiqing certificates. The opening ceremony was attended by more than 300 former zhiqing from across China, but it was not unanimously appreciated.

One critic, Hou Juan, who was a ‘celebrity zhiqing’ during the Cultural Revolution and who met Mao Zedong in person, told Fan Jianchuan directly that she felt the sculpture was inappropriate because the tone was too negative. Fan, however, insisted that the museum ought to address zhiqing deaths, too. In his explanation in an interview at the grand opening, Fan said:

The lack of medical care and the various conflicts between peasants, cooperatives, and zhiqing, all made it easy for young lives to perish under such harsh conditions … [I]n fact, they are us who died, and we are they who live. It is placed at the entrance so that everyone who enters the museum could at least greet them. (Southern Metropolis Weekly 2013)

Unlike the red hues of Heihe Zhiqing Museum, Fan Jianchuan noted, the entire exhibition space in the JMC is a refreshing light green—the colour of youth—giving the museum the appearance of a ‘green box’ that stores the youthful memories of the zhiqing generation. Fan’s personal history as a one-time zhiqing is also part of the museum. In fact, the first exhibit on display by the door is Fan’s zhiqing certificate, issued to him by the CCP in August 1975. The centrepiece of the entrance hall is a large oil painting entitled Youth (青春) by Fan’s friend, famous Sichuan painter He Duoling. The painting depicts a young female zhiqing, dressed in a green Mao suit, sitting alone in a field. The expression on her face is blurred by the dazzling sunlight, which symbolises the animated revolutionary momentum in society and the far-reaching power of Mao’s personality cult. This solitary young woman, whose state of mind is unclear to the viewer, appears to be lost in thought, reminiscing about some distant memory.

The exhibition’s presentation states clearly that the museum commemorates at once ‘the passion and frustration’ and the ‘joy and pain’ that zhiqing once engraved on that era with their flourishing youth. The exhibition is organised around four themes: history, life, tribulation, and illustrious zhiqing. Distinct from earlier Red Age museums in the JMC, the Zhiqing Museum has a much more coherent and detailed narrative of the historical context. This was possible because of existing commemorative and documentary efforts. The exhibition traces the origin of the Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside movement to an editorial published in the People’s Daily on 3 December 1953 under the title ‘Organising Senior High School Graduates to Participate in Agricultural Production’. The campaign first sketched in this article grew into a nationwide movement, with Mao’s clarion call in a 23 December 1968 issue of the People’s Daily to ‘let the educated youth go to the countryside’ (知识青年到农村去). A copy of this issue is on display in the exhibition. These snapshots of history presented through the lens of People’s Daily articles effectively set the historical context of the sent-down campaign.

By using original photographs, documents, and everyday objects, the exhibition introduces the key events of the zhiqing movement from the 1950s to the late 1970s and the stories of well-known model zhiqing figures. Supported mostly by original propaganda materials, the tone of this unit conforms closely to the official narrative. A former zhiqing aged in her sixties whom I accompanied on a visit to the museum in 2016 shook her head while going through this unit. She said: ‘Look at these young people in all these photos with big smiles on their faces. It [life as a zhiqing] was not that great. It was a lot harder. A lot harder.’ Fan Jianchuan may agree with her. For many, if not most zhiqing, the years in the countryside were characterised by intensive labour, constant hunger, and uncertainty about the future. ‘Nothing better describes the zhiqing experience than the eternal and repetitive physical labour’, Fan said, reflecting on his time as a zhiqing. He used callus, rice, and wheat as symbols of his zhiqing memories, but found they were too ‘idyllic and romanticised’ for what really occurred (Southern Metropolis Weekly 2013).

In the introduction to the second unit, ‘Zhiqing Lives’ (知青生活), Fan wrote:

[T]he lives of educated youth are special phenomena in a special era of New China. They are powerful and solemn symphonies of fate played by millions of educated youths. They were all forged in the fire of this special period.

The ‘Zhiqing Lives’ unit depicts the extremely harsh conditions zhiqing endured while working and in their private lives. On collectivised farms, zhiqing laboured to earn ‘work points’ (工分) rather than wages. Fan has displayed his own ‘work points record’ (工分本), which shows that in 1975, as an 18-year-old, able-bodied man, he earned nine work points per day—equivalent to 1 jiao (one-tenth of a yuan), at a time when the average monthly salary of an urban factory worker was 30–50 yuan (Zhao 2019: 334). The hardships of the zhiqing were the same as those borne by the farmers with whom they worked. Fan recalled in his autobiography that the only source of meat available to him as a zhiqing was pork from pigs that had died from swine fever. The exhibition tells a gruesome anecdote about seven zhiqing convicted by the CCP for eating an aborted foetus in Yunnan in 1975.

The most powerful part of this unit is an installation entitled ‘17.76 Million’ (1776万) (see Figure 2), the official number of youths sent-down between 1962 and 1979. This installation consists of several thousand pieces of broken mirror that have been scattered amid rusty hoes and shovels to fill the central atrium. These poignant symbols of hard labour and broken memories forcefully convey a haunting feeling of abandonment and desolation that features in the collective memory of the zhiqing generation.

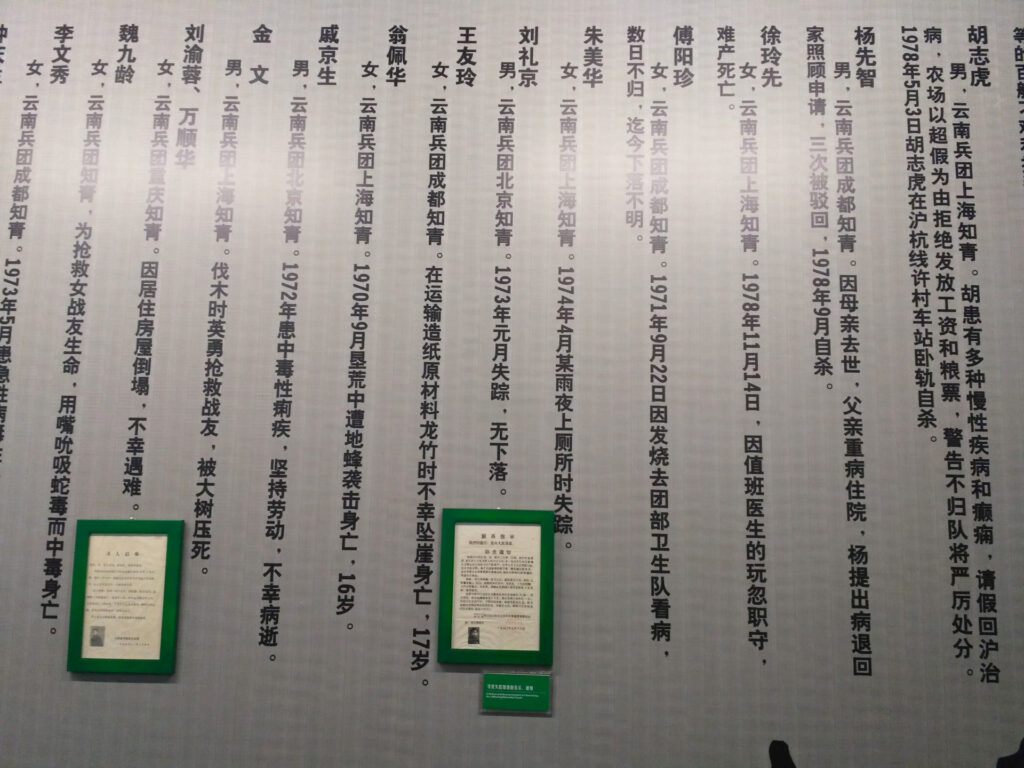

The third unit, ‘Tribulation’ (青春磨难), is engaged more directly with the violence and suffering of the rustication movement, including the physical and sexual abuse, safety hazards, and political persecution to which some zhiqing were subjected. A display in a long corridor shows a list of more than 100 incidents of unnatural death of zhiqing, including work accidents, suicide, sickness, and persecution (see Figure 3). On one side, a printed list of events is displayed in wall-length vertical columns in black and white, with the name, gender, and age of zhiqing who died, and the date, location, and cause of death. On the opposite side, black and white portraits of some of the listed zhiqing are on display. These excruciating facts and images loom like inscriptions on a mass grave.

Even in the countryside, the lives of zhiqing were affected by shifts in the political environment during the Cultural Revolution. This is illustrated by a series of ‘unjust cases’ (冤案) during the rustication movement: six high-profile cases of injustice and another eight controversial incidents. Ren Yi, a zhiqing in a county in Jiangsu Province, was a victim of injustice in the political turmoil. In 1969, Ren wrote a song entitled My Hometown (我的家乡), a melancholic tune that expressed his longing for his hometown of Nanjing and sorrow over his lost youth. The song was popular among educated youth and, in August 1969, Moscow Radio even broadcast it—at a time when Sino-Soviet relations were especially tense and hostile. In February 1970, Ren was secretly arrested on charges of ‘writing counterrevolutionary songs, destroying the zhiqing movement, and interfering with Chairman Mao’s proletarian revolutionary line and strategic plan’ (according to display text at the JMC). He was sentenced to death, though his sentence was later changed to 10 years’ imprisonment, and he was rehabilitated in 1979. As such, the JMC takes an unprecedented step in addressing the issues of death and injustice that other private zhiqing museums and exhibitions carefully avoid.

In the final section of the exhibit, ‘Illustrious Zhiqing Figures’ (知青人物), Fan juxtaposes the photographs of 32 former zhiqing who are now distinguished figures in politics, business, and the arts with a line of comment and reflection on their memories as zhiqing. These remarks show what Bonnin (2016: 763) describes as a ‘wide spectrum’ of memories of zhiqing experiences ‘between nostalgia and rejection, denunciation and approval’.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang were both sent-down educated youth. Xi (born in 1953) suffered from discrimination after the CCP purged his father, Xi Zhongxun, who was a member of China’s first generation of leaders, during the Cultural Revolution. In 1969, the 15-year-old Xi was sent down by the party as a ‘criminal’s son’ (黑帮子女) to Liangjiahe village in a poor county in the northern province of Shaanxi (Xi 2016). In this ‘strange environment’ and among ‘untrusting eyes’, Xi began his seven years as a zhiqing (Xi 2016). According to Gracie (2017), quoting Xi: ‘When I arrived at 15, I was anxious and confused. When I left at 22, my life goals were firm and I was filled with confidence.’ The museum selected ‘I’m forever a son of the yellow earth’, the title of Xi’s essay, as the quote for Xi, thus highlighting a positive official evaluation of the sent-down campaign.

This is contrasted with other comments in this section that engage more explicitly with the hardships of the zhiqing experience. For instance, Sichuan entrepreneur Liu Yonghao’s quote in the exhibit is simple: ‘I never wore shoes as a zhiqing. Steamed white rice was my greatest wish.’ Artist Xu Chunzhong is quoted as saying: ‘[T]he Cultural Revolution and the Zhiqing Movement are a trauma for me. It pains to speak about it.’ Fan’s own line, meanwhile, is brief and unequivocal: ‘I fainted twice out of hunger as a sent-down youth.’ The juxtaposition of these quotes illustrates the ambivalence and complexity of the remembrance and assessment of zhiqing history, with the museum managing to present a more balanced approach than official commemorative narratives by incorporating both positive and negative views.

Youth Wasted or Without Regret?

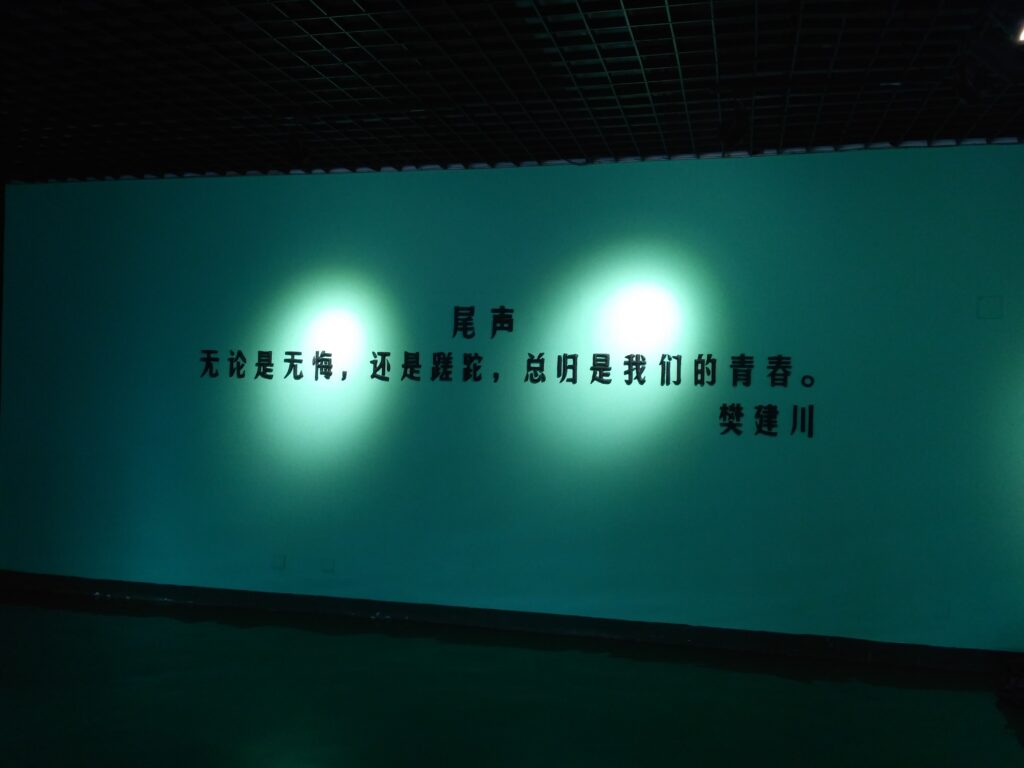

The exhibition ends with the sentence: ‘Either wasted or without regret, it was our youth after all’ (无论是无悔, 还是蹉跎, 总归是我们的青春). Running across a green wall in bold black characters, the words have a strong visual presence, resonating in the empty space. The ‘wasted or without regret’ binary acknowledges the existence of disparate views of the zhiqing movement and the possibility of remembering and transmitting it in different ways. For instance, Michel Bonnin (2016: 763) notes how the slogan-like rhetoric of ‘we have no regret for our youth’ (青春无悔) was rejected by some former zhiqing in Sichuan whom he interviewed, who claimed ‘we have no means to regret our youth’ (青春无法悔). The JMC tries to convey this kind of nuance. The second half of the sentence, ‘it was our youth after all’, voices what one may interpret as the museum’s stance—a vague and resigned gesture of reconciliation. This sense of resignation resonates with the claim by the Sichuan zhiqing discussed by Bonnin that they are not able to regret their youths for it was an experience imposed on them by the CCP over which they had no say.

Unlike other Red Age museums, the Zhiqing Museum directly addresses the tribulations of zhiqing lives with an unprecedented (and so far, unsurpassed) level of specificity by including explicit accounts of atrocious events and photos of victims. In so doing, the museum challenges the de-politicising pattern of ‘people but not the event’ that dominates both official and popular discourses of zhiqing—what Xu Bin (2021: 233) has described as ‘the lowest common denominator of various views of the past, accepted by memory entrepreneurs, local officials, and corporations involved in the production of the museums and exhibits’, with the aim to ‘decouple the zhiqing, with their positive qualities, from the controversy and political sensitivity of the event’.This has been possible partly thanks to existing efforts to commemorate this period in public. Yet, it quite understandably exposes the museum to the risk of censorship. On returning to the JMC for a second period of fieldwork in June 2016, I noticed a new item near the end of the exhibition that had not been on display when I visited six months earlier. It was a calligraphic work by Fan Jianchuan, a handwritten copy of a 17 May 2016 People’s Daily editorial entitled ‘Learning from History Is to Move Forward’ (以史为鉴是为了更好地前进), published the day after the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. Stringently in line with the 1981 ‘Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China’, the editorial characterises the Cultural Revolution as ‘the grave disaster of internal turmoil to the party, country and people of every ethnicity’ (Buckley 2016). Created and added to the exhibition in on the day of the editorial’s publication, Fan’s copy seems to be playing the role of a ‘political talisman’ to defend the museum’s approach, by drawing on the official Resolution.

A Sobering Counter-Memory

The JMC Zhiqing Museum provides a case where we can closely examine what is at stake when engaging with contested memories. As a private museum, it manages to create a space to accommodate perspectives and voices that are missing from official accounts. Running parallel to the dominant official discourse, it must also maintain a semblance of conformity to state ideology.

It is fair to say the JMC has gone further towards confronting the ambivalence of zhiqing memories than most other zhiqing museums in the country. It therefore constitutes a sobering ‘counter-memory’ that complicates the prevalent articulations of zhiqing nostalgia in Chinese society. Meanwhile, it is important to bear in mind that the museum’s unequivocal addressing of the violence and trauma of the zhiqing movement also forms a significant contrast to the silence and opacity in the historical representation of many other events of the Cultural Revolution that are in dire need of further critical attention.