Peasant Worker Communist Spy: A Chinese Intelligence Agent Looks Back at His Time in Cambodia

I was not the most qualified member of the ethnic Chinese revolutionary movement, but I was nevertheless the one who the PRC Embassy in Cambodia trusted the most.

— Chieu (2007: 77)Today, CCP foreign affairs personnel stationed in Cambodia still cherish Mr Vita Chieu with deep remembrance, and some of them sighed and said: ‘We were unfair to Vita Chieu.’

— Vita Chieu Obituary, Sino-Khmer Histories

(高棉华人史话) Facebook Page, 25 May 2020

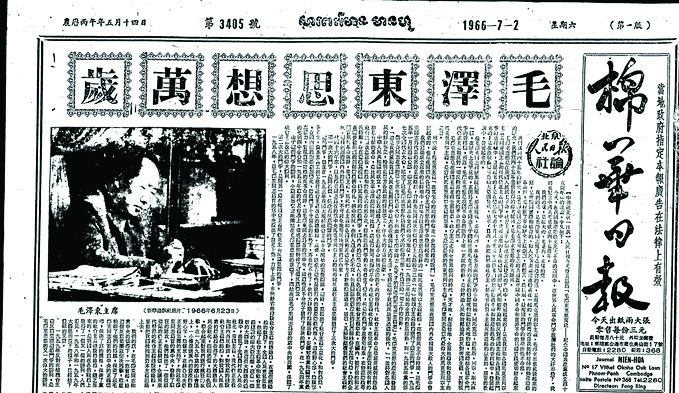

The name Vita Chieu (周德高, 1932–2020) is unfamiliar to most scholars of China and Cambodia. Few, if any, have heard of him, or know that he authored a memoir, entitled My Story with the Communist Parties of China and Kampuchea (我与中共和柬共, 2007), which details the operations of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) equivalent of the US Central Intelligence Agency or the Russian Committee for State Security (better known as the KGB), the Central Investigation Department (调查部) (Chieu 2007: 38–39, 105, 107; Faligot 2019: 104). Fewer still know that he was a translator, journalist, acting president, and managing director of the Sino-Khmer Daily (棉华日报), a popular Chinese-language newspaper that operated as the ‘official propaganda outlet’ (事事昕命于中国大使馆的宣传媒体) of the PRC Embassy in Phnom Penh until 1967 (Galway 2021: 275–76; Chieu 2007: 35–36; Willmott 1967: 89). The Sino-Khmer Daily was remarkable for its unequivocal support for Cambodian leader Norodom Sihanouk and the China–Cambodia friendship, with countless articles lauding Chinese and Cambodian leaders for their stance against imperialism. But as the Cultural Revolution erupted in the PRC, the pages of the Sino-Khmer Daily became an outlet for broadcasting radical iconoclasm to nearly 400,000 overseas Chinese (华侨) in communities across Cambodia (Galway 2021; Kiernan 2008: 288; Osborne 1994: 108).

To date, there has been little scholarship on CCP intelligence operations at home and abroad. Aside from Michael Schoenhals’ (2013) study of the CCP’s internal covert surveillance and control apparatus, the Central Ministry of Public Security

(中央公安部), during the early PRC years, we do not know much about what Chinese spy work entailed. Studies by George Xuezhi Guo (2012) and Roger Faligot (2019) of CCP security agencies and international intelligence operations, respectively, are the most comprehensive and authoritative extant analyses of CCP international intelligence work, but tend not to highlight individual experiences of agents in the field. Memoirs authored by those who worked as intelligence agents for the CCP thus emerge as eye-opening accounts that allow readers to peer through the dense, prohibitive fog and gather glimpses of what CCP intelligence work entailed on the ground—notably, outside China.

One such intelligence agent and author, Vita Chieu, was neither the only CCP intelligence agent in Cambodia, nor the only ex-spy to author a lengthy memoir of his life, career, and involvement in important events during that time. Huang Shiming (黃時明, also known as Tie Ge 铁戈), for one, was a spy who went underground when the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK)—the infamous ‘Khmer Rouge’, to use Sihanouk’s derisive nickname for the party (Becker 1998: 100)—seized control of Phnom Penh, which was a place he described as a ‘ghost town’ (Tie 2008: 643). Yet, Chieu’s nostalgic reflections on his roles with the Sino-Khmer Daily, the PRC Embassy, and the CCP as a journalist and a spy across 12 years highlight how he was an integral part of Beijing’s larger plan to broadcast Maoist enthusiasm and propaganda to Southeast Asia (Galway 2022: 55–84; Mok 2021).

This essay examines Chieu’s nostalgic reflections on his time as a journalist and CCP spy while highlighting his pivotal role at the nexus of the Cultural Revolution’s unfolding outside the PRC’s bounds. Here, I engage with Chieu’s memoir exegetically to, at once, underscore his activities as an intelligence agent and highlight how he reflected on working for the CCP even decades after resigning from the party and renouncing communism. The essay tracks his early life as a peasant worker who struggled to make ends meet to his first encounters with leftist materials and entry into the orbit of the CCP in Cambodia. It concludes with a section on his later years as a humble school custodian in the American South who held American values as paramount, yet nonetheless clung tenaciously to the idealism of his younger years.

Nostalgia and the Central Investigation Department

Nostalgia, which is defined by Svetlana Boym (2001: xiii) as ‘a sentiment of loss and displacement, but … also a romance with one’s own fantasy’, provides a particularly useful definition for understanding the force behind Vita Chieu’s attachment to his days as a left-wing journalist and communist intelligence agent. The two main features of the modern condition of nostalgia, Boym (2001: xviii) elaborates, are: 1) ‘restorative nostalgia’, which claims itself less as nostalgia and more as ‘absolute truth’ in its placing of primacy on ‘nostos’ and ‘a transhistorical reconstruction of the lost home’; and 2) ‘reflective nostalgia’, which ‘thrives in algia, the longing itself, and delays the homecoming—wistfully, ironically, desperately’. Chieu’s nostalgic retellings of his past idealism and career with the CCP are more akin to the latter category and, indeed, his outright renunciation of the restorative (highlighted, for instance, by his resignation from the CCP and ardent criticism of communism) further enunciates how much his reflections traffic in the reflective.

In his capacity as an intelligence agent, Chieu worked for the Central Investigation Department (CID), the agency responsible for collecting information on events in Cambodia. Its tasks also included, as Guo (2012: 357) details, reporting to Beijing, ‘helping the CCP’s security agencies protect CCP leaders when they visited foreign countries’, and ‘assisting CCP leaders in presenting a united front abroad’. Chieu worked under men like PRC Embassy commercial attaché and CID Guangzhou branch appointee, Wang Shuren (王树仁), who Guo (2012: 353) asserts ‘was responsible for sending CID agents to foreign countries’ during the 1960s and 1970s. Agents like Chieu who received postings at Chinese embassies abroad, as Guo continues, ‘were most likely to receive orders not from the Foreign Ministry but from the CID’ (Guo 2012: 353–54). Chieu’s (2007: 39) own recollections corroborate Guo’s claim: ‘Only then did I understand that the CCP Central Investigation Department was above the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, so they were the most important figures in the PRC embassy [in Phnom Penh].’

Chieu’s tasks as an intelligence agent were manifold. The most important of these, which I explore below, entailed working closely with PRC Embassy officials in Phnom Penh in his capacity as a journalist—often undercover to investigate overseas Chinese communities in Phnom Penh to report suspected Guomindang (GMD) loyalists to the CCP. He reported a 1963 alleged GMD plot to assassinate Liu Shaoqi when he was on an official visit to Phnom Penh that was hosted by Cambodian Prime Minister Norodom Sihanouk (reigned, 1941–55; Prime Minister, 1955–70) (Chieu 2007: 39–40). Chieu also reported ‘advance information’ that leftist national assemblymen Hou Yuon, Khieu Samphan, and Hu Nim—the first two of whom were contemporaries of Pol Pot and all three of whom were leftists with high public profiles—were to be arrested after a peasant rebellion in Samlaut in 1967 (Wang 2018: 26–27).

The location and era during which Chieu’s covert activities occurred were equally important. Chieu worked in neutral Cambodia, the PRC’s dearest regional ally amid the Sino-Soviet Split–era tensions in peninsular Southeast Asia. Cambodia’s democratically elected head of state, the former king Sihanouk, was avowedly neutral in theory and governance, occasionally to the detriment of his own National Assembly’s leftist ministers (Galway 2019: 150–52, 2022: 60–61, 130–31, 138–39; Zhai 2014; Kiernan 2004: 188–89, 197–98, 204). In holding firm to what Nicholas Tarling (2014: 4) describes as ‘a policy of neutrality’ to safeguard Cambodian independence, Sihanouk’s Cambodia stood as an important ally to the PRC to counterbalance Moscow-aligned Vietnam to China’s south. Chieu reported on, wrote, and published extensively on fraternal China–Cambodia relations during this time and, later, Cultural Revolution–inspired articles to reflect the radicalism of the era.

Peasant Worker: Vita Chieu’s Early Life

Vita Chieu was born in 1932 in Svay Cheat village, Battambang Province, Cambodia. His father was a farmer from Jieyang County, Guangdong Province, who immigrated to Cambodia, and his maternal grandmother was an ethnic Khmer from the then-French protectorate of Cambodge. Vita Chieu grew up poor but was ambitious and considerate from childhood into adolescence. He did not stay in Svay Cheat for long—drought and schooling forced him to leave home and, later, enter the workforce. As Chieu (2007: 32) recalled:

I remember when I was six years old, there was a drought in Svay Cheat and the lake was dry and tear-like. My parents fled the drought with my brother and I to Pursat province, where we lived for one year before our return. At age eight, I went to a monastery school to study Khmer in the same class as my maternal aunt and paternal uncle. Before the Japanese surrender, the Thai army occupied Battambang Province, which led me to study Thai in the monastery school for a year … At 12, my father took me to Battambang City to work as an unpaid apprentice in a bakery. From then on, I was far away from my parents and younger siblings and began to lead a vagrant’s life. One day, the son of the bakery-owner, seeing that I was young, asked me to compete with him in wrapping sweets, which he lost. He then cursed at me and called me derogatory names that meant I was a rustic, unimaginative country bumpkin who was neither Chinese nor Khmer. I was very angry, so I quit.

Betwixt and between—a Sino-Khmer of rural origins who tried to carve out a living in Battambang City—Chieu worked several odd jobs before landing at the Sino-Khmer Daily. He worked in a fruit store, then a grocery store lugging loads of river water every day. The store’s proprietor, Uncle Ung/Huang (黄伯伯, Huang Mingqiang 黄明强), discovered that he could exploit Chieu’s adeptness in Thai to speculate on gold prices and exchange rates that were wired via telegram from Bangkok to Battambang. After an unceremonious disagreement with Huang over a 72-riel balance, Chieu grew disillusioned with his employer and sought work elsewhere. As he (2007: 32) recounted, it was then that ‘I began to understand the true meaning of “boss”’.

Chieu then worked in a general store by grace of his father’s friend Yal/Yao (姚), who also provided room and board for him. Chieu assisted in keeping the store not only profitable, but also thriving after Battambang’s handover to Cambodia in 1953, the year of national independence. He earned a monthly salary of 26 riels, paid off his balance with Ung, and pooled his savings to pay for schooling. Chieu enrolled at the Battambang Overseas Chinese School (马德望侨校) elementary division, despite his advanced age for that level (he was 17). As an enrolled student, Chieu continued working after hours, handling household chores, delivering food, and doing custodial work for the school (Chieu 2007: 32–33). ‘I had suffered for as long as I can remember, so I cherished any opportunity that came my way,’ he reminisced (Chieu 2007: 34).

After four difficult years of study during which he learned to read and write in Chinese, Chieu graduated and sought out work opportunities. ‘From my start in third grade to my graduation from elementary school,’ Chieu noted, ‘those four years of sorrowful yet joyful living were deeply engraved in my heart’ (2007: 34). His first post after completing his studies was as the handler of weights and measurements for grain and, later, as a manual labourer, for a grain store in Mongkol Borey, a town in southern Banteay Meanchey Province about 60 kilometres from Battambang. A family tragedy then brought him into the orbit of the Sino-Khmer Daily and the CCP. His father fell ill, which forced Chieu to head to Phnom Penh to tend to him in the city’s Chinese Hospital. On his father’s untimely passing, Chieu nearly lost all hope: ‘My father’s death left me, as his eldest son, with sorrow and helplessness’ (Chieu 2007: 35). Now that his family was entirely dependent on the matriarch, Chieu looked for ways to provide for his grief-stricken family. In 1953, colleagues of his from Battambang pitched to him an opportunity to return to Battambang to work in community service for the Chinese communities there via the establishment of an athletic club—one that, unbeknown to Chieu at first, was CCP-endorsed (Chieu 2007: 35).

Worker Communist: Vita Chieu Enters the CCP’s Orbit

In 1953, 23-year-old Vita Chieu found himself engaged in CCP-sponsored activities that exposed him to radical ideas. As he committed himself fully to serving Chinese communities in Battambang, the CCP underground was slowly emerging from sight in the form of party-organised athletic clubs. In joining one such club, Chieu was exposed to communist literature, reading leftist writings such as Liu Shaoqi’s How to Be a Good Communist (论共产党员的修养), Mao Zedong’s speech ‘Serve the People’ (为人民服务), and Mao’s published eulogy ‘In Memory of Norman Bethune’ (纪念白求恩). As Chieu (2007: 35) recalled: ‘Absent thought, I had entered the fold and had grown familiar with figures such as overseas Chinese leader in Battambang, [Cambodia-born Chinese] Zhang Donghai [张东海], and Vietnam-born anti-French resistance figure, Cai Kangsheng [蔡抗生].’ Zhang handled overseas Chinese affairs for the CPK in Battambang and, in so doing, served as Chieu’s first direct link to the CPK underground—that is, before Zhang was ‘transferred to the Khmer Rouge in the 1950s’ (Wang 2018: 28; see also Chieu 2007: 112, 123; Carney 1989: 92).

Chieu’s interest in leftist materials, participation in CCP-endorsed athletic clubs, and ties to Chinese communists in Battambang soon won him the attention of the Battambang Overseas Chinese Party Organisation (马德望侨党组织; BOCPO). As Chieu recalled (2007: 35), in 1956, the BOCPO ‘recommended me for a post in the newly established Sino-Khmer Daily in Phnom Penh’, a newspaper that Wang Chenyi (2018: 26) notes ‘was created in 1956 by some Huayun [华运 standing for 华人华侨革命运动, an ethnic-Chinese revolutionary movement] members and the local pro-PRC leaders of various Chinese associations’. Chieu worked for 12 years as a translator, journalist, director of journalism, acting president, and managing director (1956–67). The Sino-Khmer Daily was arguably the most important Chinese-language newspaper in Cambodia. Although founded in Battambang two years before the formalisation of diplomatic relations between China and Cambodia, the paper was sponsored by the CCP via the BOCPO and affiliated with the PRC Embassy in Phnom Penh. Through this affiliation, the daily grew into China’s official propaganda outlet in Cambodia. Among as many as 13 newspapers published in Phnom Penh in 1962–63, William Willmott (1967: 89) notes, ‘five were Chinese, accounting for almost three-fifths of newspaper readership … [and] about half the Chinese adult population of the capital reads at least one Chinese newspaper daily. Many read several papers.’ Among those Chinese-language newspapers, Willmott continues, ‘the Mian-Hua [Sino-Khmer Daily] and Gong-shang [Business & Industry Daily] are the most important, carrying local and international, financial and commercial news’.

The Sino-Khmer Daily’s content made the outlet especially remarkable. Initially, it published Chinese-language articles to provide invaluable information to its readership about China’s support for, and genuine fraternal relations with, neutral Cambodia (Galway 2021: 275–76; Sino-Khmer Daily 1958b). Issues published between 1956 and 1964 were replete with praise for the Cambodian leader, Norodom Sihanouk, and lauded his commitment to neutrality and independence (Sino-Khmer Daily 1956, 1958a, 1964). As time progressed, however, the newspaper’s content reflected the increasingly radical tenor of politics in the PRC (Galway 2021: 296). Warm China–Cambodia relations increased the Sino-Khmer Daily’s popularity among Chinese communities in Cambodia, especially with CCP figures visiting the country frequently. Beijing deputy mayor Wang Kunlun (王昆仑), for one, even published poetry in one of its issues. His ‘literary style gave a face to Sino-Khmer Daily and won over many new readers’, Chieu (2007: 36) noted.

This patriotic enthusiasm went hand-in-glove with a mounting zeal for Maoist China among Chinese communities in Cambodia, and cemented Chieu’s position as an asset to the newspaper. In the 1960s, ethnic Chinese accounted for 400,000 of Cambodia’s total population of roughly six million (Kiernan 2008: 288; Willmott 1970: 6). Chinese communities in Cambodia were fiercely nationalist and, as Geoffrey Gunn (2018: 182) notes, had previously rallied together in support of China during the Japanese occupation by sending ‘donations amounting to one million piastres along with clothing in support of the nationalists’. Decades later, this enthusiasm for the homeland remained intact, albeit split between supporters of the CCP and supporters of the GMD.

In his memoir, Chieu (2007: 45) recounted that the Sino-Khmer Daily echoed the Cultural Revolution rhetoric of the day by printing ‘ultra-leftist statements’ (极左言论) in its editions. He also noted that the radical enthusiasm of the Red Guards for Chairman Mao had extended to urban and rural Cambodia via Chinese communities. The Red Guards’ ‘individual fanaticism for Mao’ extended there through the ‘transmission of overseas Chinese communities’ “homeland mindset”’, and ‘issues of Quotations from Chairman Mao flooded urban and rural areas of Cambodia’ (Chieu 2007: 36, 45; Galway 2021: 276). Chinese schools in cities and the countryside alike, Chieu notes, instructed students to ‘study the writings of Chairman Mao’ and ‘study the achievements of Comrade Lei Feng’, not unlike parallel campaigns in the PRC (Chieu 2007: 36, 45; see also Galway 2022: 72). As for Chieu (2007: 35), his class origins and zeal for the CCP made him indispensable: ‘I came from impoverished class origins. I was especially enthusiastic about, and loyal to, the Party. I was willing to go through fire and water for the Chinese Communist Party. Thus, the Chinese embassy [in Phnom Penh] trusted me completely.’

Communist Spy: Becoming an Intelligence Agent for the CCP

The CCP’s trust in Vita Chieu extended to him protecting Chinese interests in Cambodia. At a dinner party hosted by the Sino-Khmer Daily for embassy personnel, Chieu’s superior, Wang Shuren, told him: ‘You really are a Cambodia hand’ (你真是一个柬埔寨通啊) (Chieu 2007: 39). Indeed, Chieu was valuable to the PRC Embassy in Phnom Penh: a young, well-connected, enthusiastic person who could speak Khmer and Chinese and who had deep roots in overseas Chinese communities in Battambang and Phnom Penh. ‘At that time,’ Chieu (2007: 39) reflected, ‘I was young and had a good memory, so I was often consulted by the embassy on matters of Cambodian political personnel about whom the embassy was unfamiliar, which is why I earned a reputation as the “Cambodia hand”.’

As the ‘Cambodia hand’, Chieu’s responsibilities included investigating Chinese communities in Phnom Penh in his guise as a journalist to uncover who among them might be GMD loyalists. Chieu (2007: 36) recalled that his tasks entailed the investigation of visa applicants to distinguish ‘friends from enemies’:

After the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Cambodia, a large number of overseas Chinese [Chinese Cambodians] applied for visas to visit relatives in China. Because there were still members among the overseas Chinese communities in Cambodia who were GMD supporters, and I was quite familiar with overseas Chinese communities, the PRC embassy entrusted the work of ‘distinguishing friends from enemies’ [辨别敌友] to me alone. I visited various places to investigate as a journalist. Although the power to approve visas rested solely with the embassy, I wielded ‘executive authority’ [首批权] and the embassy rendered decisions based on my investigation reports.

Chieu’s recollections of his activities for the PRC Embassy during his time with the Sino-Khmer Daily reveal his devotion to the CCP and the global communist movement in general. After Sihanouk shuttered all Chinese-language newspapers in 1967, Chieu and his comrades attempted to protect the press with their lives. ‘At that time,’ Chieu (2007: 36) recalled,

a number of rightist groups sought to mobilise students to destroy the newspaper office [of the Sino-Khmer Daily], and the situation was especially critical. I was determined to lead my colleagues to defend the newspaper, and prepared myself mentally to defend the newspaper to the last man.

He continued: ‘I remember my friend, Xiao Ma [小马], intimated to me: “We may not have been born in the same year, but may we die on the same day.”’ Yet this dire, potentially life-and-death situation did not lead Chieu to reflect negatively on this period. ‘Today,’ he remarked, ‘although I have broken with the Chinese Communist Party, I still feel exhilarated every time that I hark back to these struggles. After all, when I was young, I was still a man of courage and uprightness’ (Chieu 2007: 36).

Chieu also reported on the scene at anti-government protests in Phnom Penh. In one incident, he risked imprisonment as an accused CCP spy and lost his German-made Leica camera to ‘two special agents’ of the Sihanouk government. Despite the tumult, Chieu likewise reminisced nostalgically about his and his family’s commitment to the CCP. As he recalled:

I spent my youth and adulthood in revolutionary fervour, and my wife and daughter also became members of the revolution. My wife was a bookkeeper at Sino-Khmer Daily and, later, worked as a liaison officer within and outside the [CPK] liberated zones. At eight years old, my clever and imperturbable daughter delivered letters to the PRC embassy. All of us gave our all for the revolution. (Chieu 2007: 36)

Chieu’s tasks as an intelligence agent also included the protection of major CCP officials on diplomatic visits to Cambodia and PRC-friendly leftist ministers in Sihanouk’s cabinet. He recounted that PRC Embassy first secretary Mao Xinyu (毛欣禹) called on him and two other Sino-Khmer CCP loyalists, Hong Tel/Hong De 洪德 and Uong Chong/Weng Chun 翁春, to investigate an April 1963 ‘Guomindang plot to assassinate Liu Shaoqi, his wife Wang Guangmei, Sihanouk, and the Queen Mother Kossamak’ (Chieu 2007: 39). Chieu undertook the covert operation at great risk to himself:

At that time, there was an agreement that if an unforeseen mishap were to occur, I would assume personal responsibility and not disclose [our] relationship with the Embassy, while Hong Tel and Uong Chong dealt with the Security Bureau and the General Staff Headquarters. (Chieu 2007: 53)

Mao Xinyu asked Chieu specifically to author three anonymous reports in Khmer and send them to the Security Bureau, the Department of Defence, and the royal family’s steward, the fiercely loyal General Mey Hool/Mai Hu 麦胡将军, alerting them to the plot (Chieu 2007: 39–40; Guo 2012: 357; see also Wang 2018: 26). The PRC Embassy then tasked him with tracking down and identifying suspected GMD loyalists. Chieu (2007: 40) described this task in detail in his memoir as involving undercover investigation, violence, as well as search and seizure:

The PRC embassy ordered me to scout where the explosives were hidden. On the road from Pochentong Airport to Phnom Penh’s city centre, I checked house by house to assess which houses might have burrows under them, and then went to the back of the houses to check for traces of evidence. One day, I finally found a suspicious rental house on the street, one which was less than two metres from the sidewalk. I went there with my wife, pretending to rent an apartment. During the conversation with the landlord, I found out that a middle-aged Chinese man wearing glasses lived in that house, that he had a cleft harelip with stitches, and that he was absent during the day and came back at night. Based on this facial feature, it was determined that this man was Zhang Dachang [张达昌].

At that time, with the help of activists in [the] Chinese community, the PRC Embassy had almost become a ‘national stronghold’ in Cambodia, mobilising the Chinese community to monitor the movements of GMD loyalists in Phnom Penh, even the hiding places of explosives. The embassy ordered us to make our move early to avoid unexpected circumstances. One day, a comrade came to me and told me to go to the Khmer Dance Hall on Kampuchea Krom Street at 6:25 in the evening to pester Zhang Dachang, resort to violence and make a scene, and then seize him and turn him in to the police station.

Evidently, Chieu’s deep ties to Chinese communities in the capital granted him exclusive access to insider information so he could protect PRC interests in Cambodia. In this instance, Chieu’s intelligence may have saved Liu Shaoqi’s life: ‘If we had not uncovered the plot in such a timely manner, then Liu Shaoqi and his wife Wang Guangmei may have surely died’ (Chieu 2007: 41).

Chieu’s close ties to overseas Chinese communities also connected him directly with the ethnic Chinese revolutionary movement, which Wang (2018: 26) describes as ‘a loosely formed organisation’ operated by the CCP’s Overseas Branch (侨党). ‘Under the Chinese embassy’s directive’, Wang (2018: 27) contends, Vita Chieu’s links to the movement may have saved the lives of national assemblymen, the avowedly leftist and widely popular Hou Yuon, Khieu Samphan, and Hu Nim. After Sihanouk’s policies spurred peasant uprisings in the Samlaut subdistrict of Battambang Province in March and April 1967, the Cambodian leader accused leftist ministers of instigating the rebellion. He berated Hou and Khieu for allegedly ginning up peasant unrest and threatened their lives for the role that he alleged they had played in Samlaut (Kiernan 1982: 180–82; Galway 2022: 112, 143). Both men were clearly at risk.

At the time, Hou, Khieu, and Hu were prominent members of the Khmer–Chinese Friendship Association (Samāgam Mittphāp Khmer-Chin/សមាគមមិត្តភាពខ្មែរ-ចិន; KCFA), a ‘China-curious’ association of Cambodian intellectuals, students, and politicians who supported cultural and diplomatic exchanges between Beijing and Phnom Penh (Galway 2021; 2022: 61–72). Their leading roles within the association drew the ire of Sihanouk, who, although he was the KCFA’s honorary president (see KCFA 1965) and friends with the highest rung of CCP leaders (Mertha 2014: 5–6), increasingly regarded the PRC-endorsed and funded KCFA as problematic. Hou, Khieu, and Hu all served within Sihanouk’s National Assembly, after all; their continued involvement in an association that by the mid 1960s reflected the Maoist zeal of the Cultural Revolution could compromise, in Sihanouk’s view, the neutrality that he wished to maintain at all costs. Sihanouk’s solution—strongly supported by Lon Nol’s political right-wing, which had gained traction in the National Assembly in the wake of the Samlaut Rebellion—was to neutralise all three popular ministers (Kiernan 2004: 181, 204; Chandler 1999: 55; Galway 2022: 138–43; Um 2015: 93).

Chieu (2007: 44–45) recounted how in March 1967, on hearing from members of the ethnic Chinese revolutionary movement that Hou, Khieu, and Hu were targets, he notified them immediately to ensure their safe passage out of Phnom Penh and into the CPK’s liberated zones:

At that time [in 1967], the office of Sino-Khmer Daily organised a basketball team in the overseas Chinese community. There was a young man on the team who was very close to the son of a high-ranking government official. One day in April 1967, I went on a walk with him and we passed by this high-ranking official’s house. He took me inside. The parents were not home, so the son [my friend’s friend] confided in us that the army had captured a CPK informant and they were cruelly torturing him to coerce him into providing evidence that Khieu Samphan and Hou Yuon were behind the Samlaut Rebellion. Once such a confession is made, the government will go after both of them.

I was very energetic and had many friends in the [overseas Chinese] communities, including a file clerk with the National Assembly. He provided me with copies of congressional documents and government budgets, and I often delivered them to the Chinese Embassy. This time, I reported the news about the government’s disposal of Khieu Samphan and Hou Yuon to Secretary Zhang of the Chinese embassy, who was my direct contact there. Two days later, Secretary Zhang called and asked me to go to the embassy to meet him. He ordered me to contact Khieu Samphan and Hou Yuon so that they could flee to the liberated zones as soon as possible. I am certain that he [Zhang] consulted Beijing for instructions before assigning me this task.

To alert them of the danger, Chieu rushed to a Chinese art exhibition hosted by the KCFA—likely at the Chaktomuk Auditorium, where association members often ‘conduct[ed] political activity through art’ (Martin 1989: 109; Hu 1977: 14; Galway 2021: 295). Khieu and Hou were often present at such events in their capacity as members of the KCFA press and periodicals subcommittee and inaugural committee, respectively (KCFA 1965: 6). Although Chieu’s first effort to track them down failed, he was successful on the second day of the exhibition.

Fortunately for Hou and Khieu, Vita Chieu reached them right on time. Chieu (2007: 45) recalled that he immediately relayed the information to both men, who, according to Milton Osborne (1994: 194), were ‘in genuine fear for their lives’. After informing them, Chieu received personal thanks from an unnamed CPK figure:

I told Khieu Samphan when no one was paying attention, and he immediately turned his face to Hou Yuon, and I added: ‘Please act immediately, this must not be delayed.’ A few days later, at a Khmer–Chinese Friendship Association reception, the head of the CPK underground organisation in Phnom Penh came to shake my hand and said: ‘Thank you, they have safely arrived at the revolutionary base areas.’

Disillusionment, Renunciation, Reflection

By the late 1960s, Vita Chieu was as devoted to the CCP as ever. His loyalty and consistent work on the party’s behalf led Kang Sheng, China’s internal security and intelligence czar, to organise Chieu’s first visit to China (via Guangzhou and Changsha) to report to Beijing on the situation in Cambodia. Chieu’s love of the party was on full display during a 1969 drive past Mao Zedong’s residence. A CID section chief named by Chieu only as ‘Mr Cai’ drove him by Chairman Mao’s house—a moment that brought Chieu to tears. ‘Once he and I passed the bridge between Zhongnanhai and Beihai Park by car,’ Chieu (2007: 47) recounted,

he [Mr Cai] said to me: ‘Chieu, you are very lucky. You have arrived by Chairman Mao’s side.’ He pointed out the window and said: ‘Chairman Mao lives right here.’ A warm current rushed through my heart, and tears began to flow uncontrollably. At that time, I was not yet 40 years old, but my determination to go through fire and water for the revolution was unshakeable.

Vita Chieu’s reflections on his time working for the CCP, however, change in tone by the 1970s. After his 2 January 1970 return to Cambodia, Chieu experienced first-hand the Lon Nol coup, on 18 March 1970, and the CPK takeover of the country on 19 April 1975. Between the two events, Chieu met with leading CPK figures So Phim, in early 1971, and Nuon Chea, the man who would become ‘Brother Number Two’ (that is, Pol Pot’s second-in-command), three times, but ‘never met with Pol Pot or Ieng Sary’ (Chieu 2007: 61). These meetings occurred because the CCP had reassigned Chieu and many ethnic Chinese revolutionary movement members to the CPK after the Lon Nol coup, and Chieu assumed responsibility for liaising with CPK leaders (Wang 2018: 30). Contrary to what he expected, he did not encounter much camaraderie or friendliness from his brothers-in-arms in the liberated zones.

CPK cadres told Chieu and his fellow overseas Chinese revolutionaries in 1971 that they were unwelcome. Chieu (2007: 62) voiced his protest to his new comrades:

The Chinese Embassy stationed in Cambodia notified us that we were to go to the liberated zones and join in the revolution. Every day, the Cambodian Revolutionary Organisation [CPK] also called on the people under the rule of the Lon Nol clique to make a clear class distinction between themselves and the Lon Nol clique by fleeing to the liberated zones. But instead, you are driving us to the enemy’s side.

Chieu could not understand why the CCP reassigned him to work with CPK representatives who refused Chinese assistance. He also could not comprehend why, in 1974, the CCP handed over responsibility for the extraction of Chinese operatives in Cambodia to the Vietnamese (Chieu 2007: 70–71).

Ever since the CPK became the CCP’s ‘friend’s wife’ [友妻] Cambodian overseas Chinese have become worthless ‘domestic servants’ … the CCP has taken all Cambodian overseas Chinese, including those who have been loyal to it for decades, and gifted them to the CPK. (Chieu 2007: 75)

The CCP’s communication to him and his CCP loyalists was what stung the most. ‘The CCP then officially informed us: “From now, you have no affiliation or association with the CCP” … since then, we have become orphans abroad [海外孤儿], fish meat to be cut up by CPK knives [任柬共刀组宰割的鱼肉]’ (Chieu 2007: 75). After two decades of reliable service to Beijing, Chieu’s loyalty was beginning to wane.

The CCP’s perplexing decision was one thing, but hearing about CPK atrocities against ethnic Chinese pushed Chieu to develop a seething hatred for the CPK and, later, resentment towards the CCP for abandoning overseas Chinese as ‘pawns to be sacrificed at will’ (随时供牺牲的卒子) in its superpower chess game (Chieu 2007: 79). Chieu does not mention in his memoir that he bore witness to CPK mass killings. Many Chinese experts and CCP operatives travelled around Democratic Kampuchea ‘at their own risk’ if they dared to move about freely, and if they voiced their protest to CPK atrocities, they risked compromising their livelihoods once they returned to China (Mertha 2014: 59). Chieu does recount that after the CPK captured the capital, ‘two of my cousins were executed by peasants on order from the Party’ (Chieu 2007: 52). He also noted that the Cambodian communists targeted Chinese Cambodians as class enemies because many had worked in the commercial sector before the takeover. The CPK applied this class enemy label indiscriminately. ‘CPK propagandists emulated the CCP line on class analysis’, Chieu (2007: 76) recalled, but ‘propagated that ethnic Chinese are “the bourgeoisie that sucks the blood of Cambodians.” This meant that overseas Chinese faced a more perilous predicament than Khmers.’ The CPK targeted Sino-Khmers and overseas Chinese, Kiernan (2008: 288) intimates, not because of their race, but because ‘they were made to work harder and under much worse conditions than rural dwellers. The penalty for infraction of minor regulations was often death.’ More than half of the pre–Democratic Kampuchea era population of ethnic Chinese (430,000) had died from overwork, diseases like malaria, or starvation by 1979 (Kiernan 2008: 295–296, 458).

Unable to return to Phnom Penh after the CPK takeover because the CPK forbade it, but relatively free to travel in and out of country, Chieu was safe from persecution (Wang 2018: 31). He even enjoyed the freedom to travel to Hanoi and meet with Le Duan, General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party (the CPK’s geopolitical rival and enemy), without CPK interference. The CPK, Chieu (2007: 76) noted, was ‘in deference to the CCP’ so it ‘treated those of us in the ethnic Chinese revolutionary movement fairly well’. In place of firsthand witness, then, Chieu relied on what he heard from contacts in and outside the liberated zones about killings. Of the nearly 800 ethnic Chinese revolutionary movement members who were stranded in Democratic Kampuchea, 100 died ‘in the jungles’ during those years (Chieu 2007: 64; Wang 2018: 31).

In April 1977, the CPK granted Chieu and his family safe passage to Phnom Penh so that they could return to Beijing. Grateful for an opportunity the CPK did not afford other CCP members in Democratic Kampuchea, let alone its own people, Chieu departed with the knowledge that the CCP-backed CPK was committing atrocities against ethnic minorities—notably, ethnic Chinese. He appealed to his CCP handlers in Beijing to do something about the overseas Chinese whom the party had abandoned to the CPK. His superior, Wang Tao (王涛), replied angrily:

You are so undisciplined. The Party recalls you to report, and then you are done. Why do you keep bringing up these matters? Do you still have the Central Committee in your mind? Even if someone is extracted [by the CCP] in the future, it is not according to your opinion, but instead it is the decision of the Central Government. (Chieu 2007: 79)

The reason for the CCP’s hardline stance on this matter was clearly geopolitically motivated, thus Chieu’s pleas fell on deaf ears.

Two years after the CPK’s establishment of the reclusive Democratic Kampuchea (1975–79), CCP leaders like Zhang Chunqiao (张春桥) and Chen Yonggui (陈永贵) still supported the CPK rhetorically and materially—short of sending troops—as a counterbalance to Moscow-aligned Vietnam in the region (Mertha 2014: 4–5, 9). Although it often ‘ended up as the subordinate party’, as Andrew Mertha (2014: 4) notes, the CCP maintained that the CPK leadership comprised of daring revolutionaries who were taking a brave stand against US imperialism and Soviet-backed Vietnamese adventurism. The CCP’s continued endorsement of the CPK, Chieu (2007: 39) reflected, was in contravention of the seismic shift in domestic policy in post-Mao China: ‘The Cultural Revolution was over, the CCP totally lacked discipline, and its hopes for a global revolution were completely shattered.’ ‘At that time,’ he continued (Chieu 2007: 103), ‘I already abhorred the CPK line even though the CCP continued to support the CPK as a genuine revolutionary Party.’ His confidence in the CCP shaken, Chieu’s loyalty to the Beijing line continued to erode.

As the party to which he had devoted his life and spirit continued to distance itself from him, Chieu’s disillusionment with the CCP grew ever stronger. Chieu had devoted the previous two decades of his life to serving the CCP faithfully in a range of capacities, yet he held only unofficial party membership at the time. ‘We understand your revolutionary history, but we do not recognise your organisational affiliation so you will have to formally reapply for membership’, Chieu (2007: 106) remembered hearing from an unnamed superior. Chieu nevertheless reported to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Department of Consular Affairs (外交部领事司), whereupon he urged Chinese intervention in Democratic Kampuchea to stop the killings of ethnic Chinese.

Chieu’s full report, entitled ‘The Political Line and Policies are the Lifeblood of the Party’ (路线和政策是党的生命), was written ‘according to Mao Zedong Thought’ to support his oral testimony and to communicate his steadfast commitment to the party (Chieu 2007: 103). Because of Chieu’s (2007: 103) ‘infinite faithfulness’ (无限忠实) to the CCP, he noted, his report ‘held nothing back’ in criticising the CPK. But Chieu’s report and strident criticisms therein ran counter to the prevailing Mao-era support for the Cambodian communists—a line that continued under Mao’s successor and then-PRC paramount leader, Hua Guofeng. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs quickly turned on Chieu and, in late 1977, reassigned him to Hong Kong—a move that Chieu (2007: 39, 103–4) inconsistently explains as the CCP’s attempt to shut him out and as something that was brought about ‘because of financial hardships’.

While the CCP’s betrayal of the ethnic Chinese revolutionary movement in service to supporting the murderous CPK represented a major reason for Vita Chieu to part ways with the party, the horrible conditions that awaited him in Hong Kong further drove him to reconsider his allegiance. As Chieu (2007: 39) recalled, ‘my wife and I were sent to Hong Kong, practically forced from our home without the chance to take anything with us, to do hard labour in a factory’. Chieu and his family suffered greatly after the move. They lived for a time in a slum, the infamous Kowloon Walled City (九龙寨城), and worked in a jeans manufacturing plant for the duration of their stay (Chieu 2007: 106).

Chieu’s opinion of the CCP and communism moved from faithful devotion to bitter hatred, and his family’s mistreatment in Hong Kong left a lasting imprint on him. As he (2007: 107) recounted in his memoir:

I was born in a traditional Cambodian village, and from my childhood, I yearned for the 4,000-year-old civilisation of China. I believed that my ancestral homeland was replete with heroic Communist figures. I was disappointed that I did not see or meet a Lei Feng, who found pleasure in helping others. Nor did I encounter a Jiang Jie, who had the courage to sacrifice the self. Instead, I encountered degenerate bureaucrats in Beijing who did not care about our lives. In Guangzhou, I encountered unruly shrew-like people who fought endlessly for trifling profits. Communism had not only rendered society utterly penniless, but it had also reduced human nature to its most despicable and base level. I no longer held the homeland, which had disappointed me so much, in my heart.

Over time, Chieu could not bear to put his children through ‘suffering great maltreatment and abuse in the Central Investigation Department guest house’ where the family lived. He officially submitted his resignation to the CCP office in Hong Kong (Chieu 2007: 39). Wang Shuren tried his best to persuade him to stay on, but Chieu was firm in his convictions. ‘At this point,’ Chieu (2007: 39) reminisced, ‘I was completely disillusioned with the CCP and politely refused, only promising perfunctorily to do “something patriotic”.’

It took another few years, but Vita Chieu eventually left a life of merely scraping by to support his family in Hong Kong. He lived in the British colony between 1978 and 1979 amid worsening China–Vietnam relations but relocated to Thailand in 1979 to reconnect with escaped comrades and, finally, moved to the United States in either late 1979 or 1980 (his memoir does not specify the date). In the process, from a once diehard CCP spy, he transformed into an unequivocal anticommunist critic. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, PRC paramount leader Deng Xiaoping—and, by extension, the head of Cambodian missions under Kang Sheng, the above-mentioned CID section chief Wang Tao—gradually distanced Beijing from the CPK (Faligot 2019: 104; Chieu 2007: 78, 103–4; see also Byron and Pack 1992: 356–57). By then, Vita Chieu had long parted ways with the CCP.

In a short concluding section of his memoir (2007: 111) entitled ‘Later Years of Happiness’ (幸福的晚年), Chieu describes how he settled in the United States, became an American citizen, and found work as a custodian for a high school in Greenville, South Carolina. ‘I once regarded the United States as an enemy, but today, I find that it is the most perfect place in the world and I deeply love this country of democracy, freedom, and the rule of law,’ he remarks (Chieu 2007: 111). But here, as throughout his memoir, he reflects nostalgically on his generation of true believers in the CCP mission. ‘Today’s CCP,’ Chieu (2007: 111) concludes longingly,

has ceased to reflect on these matters, and our generation’s former believers of, and active participants in, the Communist revolution are about to pass away. Most of my comrades witnessed the CPK’s devastation. Some of them escaped from CPK rule but were imprisoned by the Viet Cong for many years. Today, they are all outcasts of the CCP and scattered all over the world. I leave my experience to future generations as a token of my remorse to history.

Vita Chieu’s memoir provides us with a glimpse into the experiences of a CCP intelligence agent. His life story is replete with peaks and valleys and concludes with its protagonist at peace in a new land and with a new, albeit much more modest, occupation. But his words of longing for a time when he truly believed in something, and that something was the CCP’s mission for global communism, shine throughout his retelling of events in Cambodia, China, and Hong Kong. These moments of nostalgic reflection on the man he once was or could have been had the CCP not driven him away, shed light on a fascinating and very human story of a CCP spy’s life in one centre of the Cultural Revolution’s unfolding outside Maoist China.