The Viral Success of Chinese Village Basketball

As China’s economy struggles in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, young people have been leaving cities and returning to the countryside. In Southeast Guizhou Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture, the CunBA (村BA), or Village Basketball Association, has offered some respite from the economic gloom. Teams compete in front of raucous crowds for prizes such as live cattle and goats. At halftime, local women dressed in Miao finery perform energetic dance routines. In July 2022, when much of the country was suffering under harsh pandemic restrictions, Douyin-friendly images of a tournament held in Taipan Village, Taijiang County, went viral on the Chinese internet. In 2023, after travel restrictions were lifted, state media reported that CunBA generated a staggering RMB2.3 billion in tourism revenue for the local economy (Global Times 2023). Crowds at the CunBA finals rivalled those for the National Basketball Association (NBA) in the United States.

Officially known as the ‘Beautiful Village’ (美丽乡村) Basketball League, the tournament has been touted as a grassroots miracle of ‘rural revitalisation’ (乡镇振兴)—a silver lining in a cloudy economic outlook. In January 2024, the CunBA was written into central government policy (People’s Daily 2024a). Yet, the CunBA’s emergence as a significant, if shaky, pillar of the local economy raises questions. Is the CunBA a grassroots phenomenon or a government-led ‘Astroturf’ campaign? Who benefits from its new national audience? Is it a model of successful rural revitalisation or a symptom of a greater economic malaise?

Returning to the Countryside

After the market reforms of the 1980s, China’s coastal regions grew rich while many inland provinces were left behind. Located in the country’s southwest and home to a large ethnic minority population, Guizhou was for many years one of China’s poorest provinces. Young people flocked to coastal cities to work, leaving hollowed-out villages where only children and the elderly lived year-round. Since the early 2000s, the government has sought to address inequality through the ‘Develop the West’ (西部大开发) policy and, more recently, targeted poverty alleviation and rural revitalisation (Hillman 2023). In Guizhou, massive government investment in infrastructure such as highways and highspeed rail boosted the province’s gross domestic product. However, rural families hoping to improve their own economic circumstances were still forced to seek work in coastal areas or to relocate to larger towns or cities.

With the outbreak of Covid-19 during the Lunar New Year in 2020, migrant workers were cut off in their villages and unable to return to their urban jobs. By 2021, most of the country had returned to work and the economy was recovering, but in 2022, heavy-handed economic policy, Zero-Covid policies, and the resurgence of the virus wreaked havoc on the Chinese economy, damaging consumer confidence and exposing the precarious state of local government finances (Oi 2023). The Covid economy pushed millions of migrant workers and young people to return to their hometowns. Youth unemployment reached an all-time high before the government paused reporting in mid 2023; statistics for 2022 showed an increase in the number of people engaged in primary industries such as agriculture for the first time in two decades (Sun 2024a).

However, the government and some young people themselves have seen returning to the countryside as an opportunity. Even before the pandemic, a mix of internet-savvy rural residents and more recent urban transplants presented an idyllic version of rural life and ethnic minority cultures to millions of followers on Douyin and other social media. As the country locked down at the start of the pandemic, there was a surge in rural residents taking to social media, streaming, and e-commerce platforms to promote local culture, produce, and their personal brands. The return to the countryside and the rise of rural influencers and e-commerce have been cheered by the government as it seeks to combat poverty and revitalise rural areas through tourism, cultural heritage, and the digital economy. One of the most successful models of this kind of internet-driven rural revitalisation is the CunBA.

The CunBA Goes Viral

Basketball has a long history in China and is ‘perhaps the only true national sport’ (Gao 2012). It was first introduced by missionaries in the nineteenth century and, under Mao Zedong, gained popularity in universities and the People’s Liberation Army. In Guizhou, steel hoops and concrete courts dot the countryside alongside temples and paddy fields in village after village. As a Taipan resident explained to a Chinese journalist, ‘during the harvest we dry grain’ on the court; ‘in the slow season, we play basketball’ (Su and Chen 2022). Tournaments are timed to coincide with local holidays such as the lunar ‘Double Six’ (六月六) festival. The tournament in Taipan dates back decades and is now a multigenerational affair (Xu and Da 2022). But in July 2022, images captured by a visiting photographer exploded online, exposing the competition to a new national audience.

The ‘discovery’ of the CunBA has been credited to a young photographer named Yao Shunwei, who was born in rural Guizhou. After graduating from Northern Minzu University in 2016, he returned to Guizhou and opened a studio in Guiyang, the provincial capital, where he worked shooting weddings and promotional videos. In June 2022, Yao posted video of dragon boat racing in Taijing County to Douyin, where it was quickly reposted by locals. But, as he explained in an interview with local media, he soon received a message from an account in coastal Zhejiang Province asking to use his images to promote China’s ethnic minority cultures abroad (Cao 2023). Shortly after, Yao’s Douyin account was followed by then Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian, best known for his ‘Wolf Warrior’ keyboard diplomacy, who reposted his video to Twitter (now X).

The next month, Yao Shunwei found himself watching a livestream of Taijiang’s ‘Double Six’ basketball tournament. A basketball fan himself, he was struck by the unusual fervour of the players and the crowd as play ran into the early hours of the morning. On 20 July, he drove to Taijiang to shoot the finals. The following day, he uploaded a 4-minute video to Douyin. Set to the 2017 song Infinity by American singer-songwriter Jaymes Young, Yao’s video shows a remarkably professional contest playing out against the night sky and improbably steep stands. The clip quickly racked up views and likes and, within half an hour, Yao received a call from Douyin informing him that his video would be promoted across the platform (Han 2023).

Yao’s video was already spreading quickly on Douyin, but village basketball became a cultural phenomenon after the footage was reposted to Twitter by an account in Zhejiang and retweeted by Zhao Lijian the next day. Twitter (now X) is banned in China, but screenshots of Zhao’s tweet extolling the tournament’s ‘great atmosphere’ were carried by state media and began circulating ‘wildly’ on the Chinese internet. Within days, internet users had renamed the tournament ‘the CunBA’. When local players invited Yao Ming, the NBA legend and current head of the Chinese Basketball Association (CBA), to Guizhou, he jokingly responded that he would not be able to get a ticket. He claimed that a four-day tournament in late July was streamed more than 100 million times online (Global Times 2022).

Officials in Taijiang were familiar with the tournament’s large, in-person crowds, but they were quick to capitalise on the new national audience. Taipan’s basketball court was built in 2016 and the vertiginous stands were added two years later to accommodate the growing crowds (The Paper 2022). After the tournament went viral in 2022, the Taijiang County Government announced funding to upgrade the facilities, including a new media centre, in time for the 2023 season (Li and Bu 2022). When I visited Taijiang in mid 2024, Taipan had been reconfigured around the CunBA stadium and statues of its mascot, a bandana-wearing bull atop a basketball—a nod to the local tradition of water buffalo fighting (Chio 2018). At the same time, new basketball courts tiled in the CunBA’s signature red and green had been installed in villages across the county.

The Taijiang County Government was not the only one to take an interest in the CunBA. In neighbouring Rongjiang County, enterprising local officials promoted Cunchao (村超), or ‘Village Super League’, a football (soccer) tournament that drew enormous crowds to its inaugural competition in 2023 (Aw 2023). The NBA also saw potential value in the CunBA and its audience of millions. In September 2022, it hosted a ‘Rural Basketball Championship Cup’ in Quanzhou, Fujian, with its broadcast partner Kuaishou (Green 2022). In 2023, the Australian NBA star Ben Simmons donated a basketball court in Machang Township, Guizhou (Basketnews 2023). In July of that year, Jimmy Butler, an NBA all-star who wears shoes by Chinese sportswear giant Li-Ning (Jeong 2023), became the first NBA player to attend a CunBA match in Taipan, where he addressed the crowd draped in Miao silver jewellery.

The central government also took note of the CunBA’s success. In 2024, CunBA and Cunchao were written into government policy as exemplars of ‘rural initiative’ (农民唱主角) and ‘collective cultural and sporting activities’ (群众性文体活动)—models of rural revitalisation to be supported and emulated across the country (People’s Daily 2024a).

Grassroots or Astroturf?

Was the CunBA’s viral success a grassroots phenomenon or the result of a government-led ‘Astroturf’ campaign? In local media interviews, Yao Shunwei describes being approached by the mysterious Zhejiang Douyin account and how Zhao Lijian’s tweet ricocheted across the internet. Sport has long been an instrument of China’s cultural diplomacy, from ping-pong players in the 1970s (Millwood 2022) to the Beijing Olympics in 2008 and Winter Olympics in 2022. Indeed, before Yao’s video went viral, Zhao had already tweeted several images of people playing basketball in surprising rural settings without much response. The CunBA has received some coverage in international media, seemingly all positive. The unexpected turn was that, if Zhao aimed to reach a foreign audience, he found a larger, more receptive audience at home.

The CunBA has its own grassroots appeal. It is often described as ‘down to earth’ (接地气)—a term that refers to its amateur, rural qualities: livestock as prizes, local halftime entertainment, players and spectators from all walks of rural life. (By contrast, Cunchao, played on actual Astroturf, was essentially a local government initiative.) There may be a degree of wistfulness and, indeed, condescension in urban viewers’ perceptions of the simplicity and authenticity of rural life (Zhao 2023). And minority groups like the Miao have long been subject to ‘internal orientalism’ in media and popular culture (Schein 2000). Yet, the CunBA is often explicitly contrasted with the CBA, which is infamous for its glossy production values, mediocre basketball, and allegations of corruption (Lu 2023). In contrast to the CBA, CunBA is described by commentators as ‘relatable’. This is perhaps partly because a significant segment of the CunBA’s audience online are current or former rural residents.

Nor can the emergence of the CunBA be separated from Zero-Covid policies, nor indeed, the virus itself. When Yao Shunwei’s video went viral in the middle of 2022, large parts of the country were under harsh, unpopular lockdowns. Commentators noted that almost none of the spectators was wearing a facemask (Feng 2022), with some reports chalking this up to the success of the government’s Zero-Covid approach (Huang et al. 2022). Not long afterwards, the situation worsened. On 18 September, amid a spike of cases in the province, a bus carrying people to a quarantine centre south of Guiyang overturned at 2 am, killing 27 passengers and sparking anger and anguish online. On 24 November, a fire in Ürümqi, Xinjiang, killed 10 people, leading to nationwide protests and, ultimately, the abrupt, devastating end of the country’s Zero-Covid policies. Amid the harrowing collapse of Zero-Covid and the economic malaise that followed, the government and the media found a much-needed good news story—a distraction. And so did ordinary people.

A Day at the CunBA

In July 2024, I visited Taipan on my first trip to Guizhou since I was forced to leave my fieldwork at the beginning of the pandemic. I had not visited Taipan before, but it had clearly been transformed by its sudden fame. The road was marked by billboards touting the ‘birthplace of the CunBA’ and a statue of the mascot stood on a roundabout at the entrance to the village. A giant screen beside a CunBA-themed restaurant streamed the action inside the stadium. There was a CunBA gift shop and a sign promoting ethnic ‘intercourse, exchange, and integration’ (交往交流交融) and ‘solidifying a sense of community for the Chinese nation’ (铸牢中华民族的共同体意识)—the current watchwords of the government’s ethnic policy. Entry was free, but spectators were required to swipe their national ID cards at the gate or submit to the now-ubiquitous facial recognition cameras.

The first game of the afternoon was a friendly match between Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management and a local Taipan team. The crowd was small at first and sheltered from the sun under hats, umbrellas, or the shadow of the new media centre. A lone journalist from China Central Television (CCTV) was filming take after take as he sweated in the sun. At halftime, men and women in Miao costume filed on to the court to perform a vigorous dance routine that belied their relatively advanced age. Historically, summer festivals were an opportunity for Miao youths to court and flirt (Chien 2009), but with most young people still working in coastal cities, the CunBA halftime performers were middle aged or older.

As the tournament resumed, the stands began to fill. The crowd was mostly local with a smattering of tourists. Several young women appeared on the sidelines, livestreaming the game on their phones, and pulling players aside for interviews. A local television host arrived with camera crew in tow, and the evening began to resemble a TV variety show. There was karaoke, a pork-knuckle eating contest, watermelon wrestling, a high school basketball game, and a game between teams of Miao ‘aunties’. As the final began about 10 pm, it became clear that the crowd was not there for what turned out to be a pedestrian, one-sided contest, but to catch a glimpse of three-time NBA champion Danny Green.

Even before the halftime buzzer, crowds were mulling around the ends of the stadium and, during an extended break from play, men playing the lusheng, a traditional Miao musical instrument, and women bedecked in silver paraded across the court. They were followed by an intense media scrum, with Green at its centre and towering above it. He shot three-pointers and played one-on-one with local players and was enticed to say a few words in Miao and ‘wo ai CunBA’ (‘I love CunBA’). He was presented with Miao silver jewellery (usually worn by women), signed a basketball, posed for photos with CunBA officials, and finally joined a circle dance before retiring to the stands. As play resumed, people poured out of the stadium and into the night.

Who Benefits from the CunBA?

The CunBA caters to several different audiences and agendas. There are the 20,000-odd spectators in the stadium, most from the local area, there to enjoy the tournament, the spectacle, and the ‘hot and noisy’ (热闹) atmosphere. Then there are the millions of people around the country who stream matches online or consume them on social media. For the government, it has been a public relations coup, showcasing rural revitalisation and ethnic harmony amid the tense, post-Covid environment. For streaming and e-commerce platforms, and the NBA, the CunBA’s online audience is seen as a promising stream of revenue. Record-breaking tourist numbers in 2023 and 2024 (People’s Daily 2024b) suggest that local governments and businesses are already profiting from the CunBA’s newfound popularity.

But does the CunBA benefit local communities? Since the market reforms of the 1980s, tourism and cultural heritage projects in Guizhou have packaged minority culture and identity for the consumption of outsiders and transformed villagers’ lives and livelihoods (Oakes 1998; Schein 2000). This can be a profoundly discomforting experience for local people, particularly when heritage orders are imposed from ‘above’ (Chio 2024; Rautio 2024). Moreover, tourism proceeds inevitably benefit some residents more than others. During a decade of research on southeast Guizhou, I have seen the character of some villages transformed dramatically by tourism. I have also seen how tourism and cultural heritage have created employment and opportunities in villages where previously there were none. While the well-honed version of Miao culture performed at the CunBA might be simplified and commodified, I would not begrudge communities who have faced centuries of discrimination (Wing-Lun 2022) the chance to capitalise on their cultural difference.

Rural revitalisation, like the earlier ‘Develop the West’ and poverty alleviation policies, seeks to address vast economic disparities that have been decades in the making. The current economic malaise has forced young people back to rural areas and, in the eyes of the government, the CunBA and Cunchao can create jobs and make hollowed-out villages whole. Many working-aged people would happily return to villages, and their families, if given economic opportunities. But people in their twenties and thirties grew up in a booming economy ‘raised on stories of economic dynamism and social mobility’ (The Economist 2023). Many expected to make a life in the city and would probably prefer urban employment if economic conditions allowed. Some young people in Guizhou, like the photographer Yao Shunwei, have willingly returned home to work in tourism or primary industries, but for others, it has been less of a choice than a last resort.

Whether the CunBA’s popularity can be sustained is also an open question. Since the end of Zero-Covid in December 2022, Guizhou has experienced an enormous boom in ‘revenge travel’ (Yang and Peng 2024). However, a worsening economic outlook could cause tourists to close their wallets (Sun 2024b) and, with intense competition for eyeballs, it could be difficult to maintain online interest in years to come. The CunBA’s viral fame could yet prove fleeting. Despite this uncertainty, village basketball will carry on regardless, even if there is no national audience or any NBA stars or CCTV journalists sweating on the sidelines.

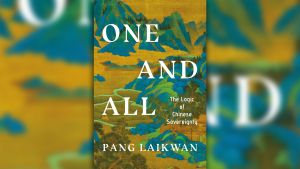

Featured Image: A CunBA game in Taipan Village, July 2024. Source: Joel Wing-Lun.

References