Navigating the Market for Love: The Chinese Party-State as Matchmaker in the Early Reform Era

The People’s Daily (人民日报) publishes important announcements on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It covers high-level politics, economic achievements, diplomatic breakthroughs, and other serious topics. So, on 14 December 1984, a reader might have been surprised to see the paper run the playful headline ‘Interprovincial Dating Project’ (跨省市恋爱协作) (People’s Daily 1984). The article in question reported that many women workers in Jinzhou, Liaoning Province, were having a hard time finding a husband, while the Dagang oilfield in Tianjin had numerous single male workers. After learning about the situation, local trade unions had decided to cooperate and initiated several interprovincial blind dates: more than 40 Jinzhou women had travelled to Tianjin, while 50 Tianjin men had travelled in the opposite direction. Within four months, 39 women from Jinzhou had begun romantic relationships with workers from Tianjin and five planned to marry in a collective wedding hosted by the union in the new year. With such flowers of love in bloom, the state newspaper declared the dating project a success.

The Birth of the ‘Older Youths’

Why did the Chinese Government, which at that time was supposedly preoccupied with ‘eliminating chaos and returning to normal’ (拨乱反正) after the end of the Mao years, suddenly take an interest in sponsoring dating projects? It all started with a meeting earlier in the summer of 1984. On 10 June, the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the CCP had convened to discuss what it called the ‘older youths’ marriage problem’ (大龄青年婚姻问题). On that occasion, top officials had ordered the mass organisations—the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), the All-China Women’s Federation, and the Communist Youth League of China—at every administrative level to pitch in. While maintaining the official line that marriage should occur later in life to control population growth, participants at the forum deemed that marrying too late and staying single were problematic as well. The ideal window for marriage was arbitrarily set to be from the age of 25 to 30 for men and 23 to 30 for women. With its characteristic ingenuity with words, the government came up with the paradoxical phrase ‘older youths’ (大龄青年) to describe those who remained unmarried beyond the age of 30 (Wang and Li 1989: 551).

The Chinese State has historically intervened in marriage and family affairs. During the Qing Dynasty, various legal codes regulated parent–child relationships, marriage practices, and ‘proper’ sexuality as part of the state’s civilising project (Du 2021; Theiss 2004; Sommer 2015). In the eighteenth century, as a result of a skewed sex ratio, especially in rural areas, single men—known as ‘bare sticks’ (光棍)—were ostracised and suppressed as the Qing State perceived them as a threat to social stability (Sommer 2000: 10). The Party-State of the early reform era inherited such concerns and officially problematised the unmarried population in 1984.

This unease was not entirely unwarranted. The transition from decades of revolution to the policy of Reform and Opening-Up in the early 1980s had given rise to cultural shifts and social dynamics that transformed marriage practices. During the 1960s and 1970s, young people upheld a person’s political background as the most important criterion when finding a romantic partner. Party members, workers, and soldiers were considered the most desirable for their ‘progressiveness’ (Yu 1987). However, as revolutionary fervour dwindled in the late 1970s, one’s political background quickly lost its appeal and marriage for love came to be celebrated instead.

Yet, practical concerns remained crucial criteria in selecting a spouse. The Chinese traditional view that favoured educational attainment in the selection of one’s partner regained prominence in the wake of Deng Xiaoping’s decision in 1977 to restore the college entrance exam. And once people were no longer accused of being bourgeois and counter-revolutionary in their pursuit of a cultured and upper-class lifestyle, economic status also became a priority in mate choice, especially for women (Cai 1989: 25). Women workers no longer wanted to marry peasants or men working in the service industry, while male workers still expressed some interest in women from those occupations (Feng 1985: 56). In fact, it was believed that one of the major reasons for the growing number of single women was their unwillingness to marry their fellow workers (Shang 1994: 40).

While marriage culture began to shift at the start of the reform period, broader social dynamics that had their roots in the Mao era were also at play. Beginning in the 1950s and expanding during the Cultural Revolution, the ‘Down to the Countryside’ (上山下乡) movement mobilised millions of urban youths to labour alongside and learn from peasants in rural villages (Bonnin 2022). While these youths maintained an active romantic and sexual life in the countryside, they rarely tied the knot. The household registration system (户口) made it difficult for urban youths to marry their rural partners and an urban–rural union could complicate their plan to go back to the cities (Honig 2003: 160). Thus, most of the urban youths returned home in the late 1970s as male or female ‘bare sticks’. This, however, was not the end of their problems. The mass return of Chinese young people to their city homes precipitated a labour surplus, which in turn caused urban unemployment to rise. The bare sticks therefore struggled to sprout since being jobless did not bode well in a new marriage market that valued one’s economic status.

These developments engendered much anxiety and discontent. Many sent-down youths felt they had been sacrificed, abandoned, and even betrayed. In the 1970s, they had enthusiastically answered the Party-State’s call, delaying marriage and dedicating the best years of their lives to carry out the revolution in the countryside. Yet, when they returned, they discovered that their chances of marrying were further diminished and their marital status was a subject of intense social scrutiny. As a young man from Beijing pleaded with researchers investigating the ‘older youths’ problem in the 1980s: ‘We are the most miserable among the miserable generation. We got involved in every unfortunate situation. What does society plan to do to take responsibility [for our misfortune]?’ (Older Youths’ Marriage Problem Investigation Team 1985: 40).

Building a Magpie Bridge

Unsettled by these developments, the Party-State took a proactive stance. Two days after the secretariat meeting in June 1984, the Women’s Federation organised a national conference to discuss the marriage problem. On 18 June, the ACFTU also held a forum to address the matter by examining existing matchmaking initiatives. The two mass organisations concluded that they would set up special units to ‘build a magpie bridge’ (搭鹊桥) and ‘pull the red thread’ (牵红线)—references to Chinese legends about fated lovers—by organising activities and creating opportunities for youths to socialise (Zhang 1984).

The CCP in fact has something of a track record in matchmaking. Mao Zedong famously praised the character Hong Niang (红娘), the matchmaker between the two protagonists in the classic play The Romance of the West Chamber (西厢记), for her chivalry and for standing up for choice in love (Chen 1996: 1349–50). He matched Liu Shaoqi with He Baozhen during the Anyuan strike of 1922 and reportedly enjoyed matchmaking for those around him. Other communist leaders such as Zhu De, Zhou Enlai, and Deng Xiaoping served as matchmakers at some point (Li 2016: 143). While the CCP sought to dismantle some aspects of traditional marriage, matchmaking remained a critical and popular practice. What changed in 1984 is that for the first time in Chinese history these individual practices became a concerted effort backed by the government.

Following the national forums’ directives in June, local branches of the mass organisations quickly went to work, with the unions spearheading the initiative. In August that year, the municipal union in Changde, Hunan Province, founded the Changde Marriage Broker Agency (常德婚姻介绍所) and established 122 matchmaking units within union branches at the factory level (Editing Committee of the City Gazetteer of Changde 1993: 512). In Zhengzhou, Henan Province, the municipal union built a matchmaker network among factories and mines (Women of Zhengzhou 1989: 114). And in Tianjin’s Nankai District, the union formed a team of more than 700 matchmakers—something they had pioneered from the early 1980s—and went on to found the Tianjin Matchmaker Association (天津市红娘协会) in 1990, which attracted more than 14,000 members in just two years (Jia 1993: 431). For their active contribution to help older youths, some union matchmakers were even awarded titles that resembled those of model labourers. In 1985, the union at a workers’ college in Hubei Province organised a competition for 10 categories of model workers, one of which was ‘progressive matchmakers’ (先进红娘). On Women’s Day the following year, the union awarded five matchmakers in this category (Pang 1999: 170).

Taking advantage of the unions’ organisational infrastructure—which had often been used to organise recreational activities for workers—these new teams of matchmakers came up with a variety of activities to build a magpie bridge between female and male workers. A Beijing construction company’s union organised regular weekend dance parties for work units that had large numbers of women. On holidays such as National Day and Labour Day, the matchmaking units held ‘magpie bridge’ events for young workers to mingle (Duan 1988). The marriage agency of a Zhengzhou union even held movie screenings, games nights, and took hundreds of older youths on excursions to suburban tourist attractions (Women of Zhengzhou 1989: 114).

In addition to holding large-scale social events, the matchmakers worked on a more personal level at their newly established matchmaking offices by helping older youths to find matches individually. A coalmine in Fujian Province made national headlines in 1982 when its union pleaded with the public to help in the miners’ struggle to find wives (Li 1982). After reading the news in the Workers’ Daily (工人日报), many young women wrote to the coalmine, expressing their interest. The matchmaking office collected letters and photos from young women, took note of their preferences, put them into files, and encouraged male workers to submit a profile and request a match. Workers’ applications included a photo of themselves, their age, height, family background, education, occupation, self-described personality, and what they were looking for in a spouse.

After reviewing a worker’s information, the matchmaking office would select a small number of potential matches from the women’s profiles and show the photos to the worker. Letters and photos from women were treated as classified documents and not available in large numbers as matchmakers were worried that amorous men would be distracted by too many options. After looking through the files of several women, the worker would decide whether there was a ‘red thread’ with one of them. If he found someone especially attractive, the office would share the woman’s contact information and let the two start correspondence via mail (Li 1991: 10). In the case of the Fujian coalmine, the application procedure at the matchmaking office gave male workers the power to choose because in that context they were the majority. In other matchmaking offices, female workers could also initiate applications. The tendency to frame the campaign as a way to help older men find wives was possibly due to the skewed sex ratio in the older youth population, in addition to the idea that single men posed a greater threat than single women to social stability.

The Interventionist State

The matchmakers’ job did not end after a match was made. As the Tianjin–Jinzhou interprovincial dating project suggests, matchmakers also played a crucial role in sealing unions by hosting collective weddings. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Nationalist government first popularised collective weddings as a way to modernise the ceremony (Ayscough 1937: 64–65). In the late 1970s, weddings became increasingly extravagant, in part as a reaction to the suppression of such ceremonies during the Cultural Revolution. To reinstate a frugal spirit and lessen the financial burden on young couples and their families, the Party-State began promoting alternative wedding models, such as travelling and collective ceremonies (Honig and Hershatter 1988: 147–55). The new matchmaking teams thus included collective weddings as the final act of their mission.

The procedure of the collective weddings is worth noting here. Trade union leaders, party secretaries, or factory heads—mostly men—usually served as officiants. They were the first to give a speech, followed by brief remarks by a guest and occasionally by representatives of the couples’ parents. The tens, sometimes hundreds, of couples first read a prepared statement, then bowed three times to the wedding officiants, three times to the guests, and three times to each other (Yang and Wang 1984: 89–90). The conspicuous presence of political leaders at the wedding ceremony invited the state into a moment of familial celebration.

Not only did the collective wedding exemplify political leaders’ involvement in family affairs, but it also revealed how the state wielded patriarchal authority, even within ostensibly personal matters. Traditional Han Chinese wedding ceremonies culminate in three bows: first to Heaven and Earth, second to parents and family elders, and third between husband and wife. Conveying a message of veneration and gratitude, the first two sets of bows are directed towards the authority figures in family affairs. By retaining the bows in the ceremony, the supposedly modern collective wedding retained the differential power dynamic deeply rooted in the marital rituals between the young couple and family elders. To denounce the ‘backwardness’ of traditional marriage and patriarchal oppression, the Party-State could have simply done away with official remarks and the bows and asked a worker peer to officiate the collective wedding. Yet, the state adapted the bows instead and replaced Heaven and Earth with the union leaders and factory heads. In this vital ritual, the male political leaders surpassed everyone else to be the first to receive the couples’ bows and deliver remarks (Wu et al. 1988: 228–29). It was therefore not that the state tried to abolish patriarchal authority in the family. Rather, it deployed political leaders, usually older men, to exploit such authority.

This interventionist ethos indeed underlay the state’s response to the older youth problem. When grassroots cadres raised doubts about the matchmaking campaign, contending that dating was a private business and did not merit public resources and mobilisation, the government made clear that dating, which would lead to marriage, was in fact a public matter. For instance, a Women’s Federation official from Tianjin reported that there were about 60,000 older youths in Tianjin by the mid-1980s. She reasoned that the marriage problem did not just concern these individuals but was also a burden to their friends and family. Now that millions of people were involved, the issue was no longer private and required a public solution (Wu et al. 1985: 228).

At the 1984 national forum, the ACFTU secretary Li Xueying further emphasised the marriage problem as a public issue to justify the matchmaking campaign. She argued that as marriage was a major life event, its absence could impact production and the country’s development and modernisation (ACFTU Department of Women Workers 1989). Significantly, the Party-State’s open discussion of marriage and the public campaign for matchmaking also reversed its previous culture of silence around romance and sexuality. During the Cultural Revolution, work units forbade young workers from showing their affection in public, whereas in the reform era, organised matchmaking brought affection to the public spaces of shop floors, workers’ clubs, and union meetings.

After framing the marriage problem as a public responsibility, the Party-State’s intervention in workers’ personal lives became more comprehensive. In her speech, Li Xueying stressed the importance of matchmakers to instil the ‘correct values’ for dating (正确的恋爱观) among the older youths. Given the recent cultural shift in mate choice, the matchmakers should undertake political thought work and advise the older youths to not overly prioritise one’s physical appearance and economic status, not hold their standards too high, objectively evaluate oneself and others, discard old customs and traditional biases, and, of course, participate in birth planning (ACFTU Department of Women Workers 1989: 318). Publications by the ACFTU even went as far as giving fashion tips on what to wear on the first date and advising couples to control their sexual arousal when sharing a hug or a kiss (ACFTU Department of Propaganda and Education 1989: 1247–48).

Legacies

It is hard to conclusively determine the degree to which the 1984 matchmaking campaign succeeded in addressing the problem of older youths. The national forums never put forth any statistics about the changes in the rate of single youths and the initiative was largely carried out at the local level after 1984, exiting the national discourse. The mass organisations only catered their matchmaking programs to young people formally employed within the work-unit system. Unemployed youths, who were the most marginalised in the marriage market, had to seek help from matchmakers established by subdistrict offices and neighbourhood associations.

But the campaign did leave its mark. The Party-State’s initiative led to the rapid growth of marriage broker agencies in many cities. The matchmaking events provided a much-needed venue for youths to socialise when there were few entertainment arenas in the early reform era. Although there are no national data, a study comparing Beijing’s census figures from 1982 to 1990 shows that the percentage of unmarried people aged between 33 and 40 dropped from 9 per cent to 7.9 per cent (Zhou 1992: 30). A single data point cannot establish causation, but it does indicate that the phenomenon of older youths, created by the sociohistorical conditions of the late 1970s and early 1980s, was somewhat relieved by the end of the decade.

The unions’ matchmaking project also became a crucial part of the welfare benefits workers enjoyed. As China pushed forward with marketisation in the 1990s, the model of official matchmaking disintegrated along with the collapse of the work-unit system. This paved the way for commercial matchmaking agencies. When matchmaking corners popped up in city parks in the 2010s, retirees who tried to matchmake for their children became nostalgic for the 1980s. Historian Sun Peidong (2012: 85) recalls one of these elderly people telling her in the late 2000s: ‘In the past the Women’s Federation, the Youth League, and the trade union would organize activities for the youths to socialize. How come no one is doing it now?’

If history offers us any lesson, it would be that the Party-State does not hesitate to step in when perceived ‘social problems’ crop up. The matchmaking campaign in the early reform era in many ways served as a prelude to the Chinese Government’s response to the marriage crisis in the twenty-first century. In 2020, to counter the declining marriage rate, the government instituted a 30-day ‘cooling-off period’ for divorce (离婚冷静期) and, in 2024, it simplified the bureaucratic process for marriage registration, despite popular opposition. The Women’s Federation’s stigmatisation of ‘leftover women’ (剩女) for being picky in the 2000s echoed the organisation’s earlier complaints about women workers not wanting to marry male workers and its promotion of the ‘correct value’ of not holding too high a standard when looking for a suitable partner (Fincher 2013). With the end of the marriage crisis nowhere in sight, the Party-State will probably once again lend Chinese youths a paternalistic and interventionist hand to navigate the market for love.

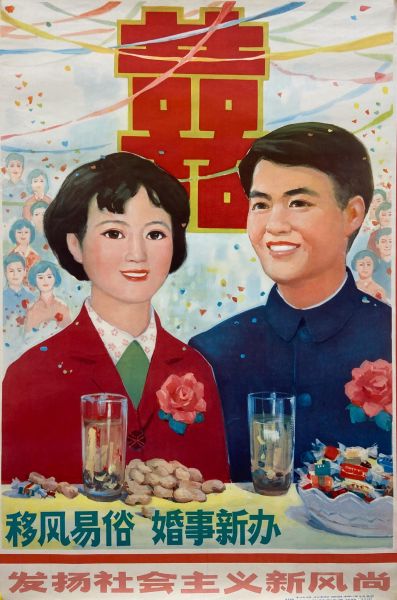

Cover Image: Zhang Anpu, ‘Transform Social Traditions, Hold a New Wedding’ (1982). Photo courtesy of the Wesleyan University Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies Art & Archival Collections.

References