Land Wars: A Conversation with Brian DeMare

The Maoist land reform campaigns were an integral element in the Chinese Communist Party’s rise and subsequent ability to maintain power. In Land Wars: The Story of China’s Agrarian Revolution (Stanford University Press 2019), Brian DeMare weaves together historical and narrative accounts, providing a detailed picture of how the land reforms shaped the lives of those involved, as well as communist rule in China.

Nicholas Loubere: Maoist land reforms did not happen in a void. Can you tell us about the agrarian revolution’s historical antecedents and the ways in which the Chinese Communist Party portrayed the movement as it was occurring?

Brian DeMare: For Chinese farmers, ownership of land and access to fields have always been existential issues. In the aftermath of the imperial era, Chinese reformers and revolutionaries were well aware of the importance of the ‘land problem’: some farmers prospered, but many lacked land and struggled to make ends meet. The Nationalist and Communist parties recognised the need to reorganise agricultural holdings, but leaders in both parties were hesitant to focus on rural poverty. Under Sun Yat-sen, the Nationalists had issued a call to give ‘land to the tiller’. This was a popular slogan, but after the rise of Chiang Kai-shek the Party increasingly relied on village landlords and rural power-holders. These men had little interest in agrarian reform. As for the Communists: true to the tradition of China’s urban elites, which sadly continues until today, they viewed villagers as backward and uneducated. They sought to carry out a proper Marxist revolution by organising the urban proletariat. As one early Communist leader argued, farmers did not want collective ownership, but their own private property.

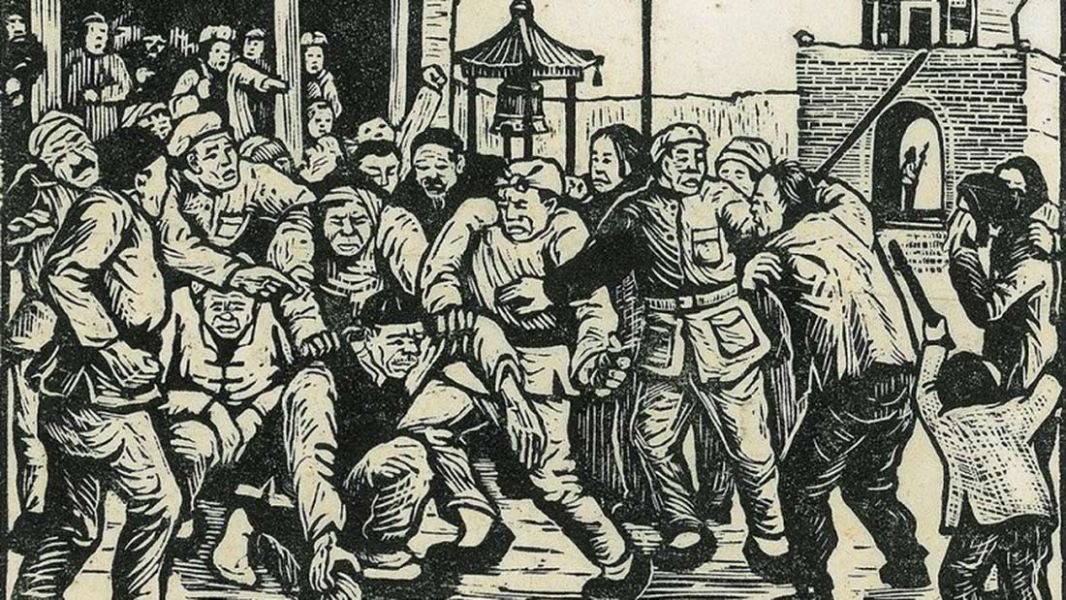

The total failure of the Communists’ urban revolution, however, encouraged some Party members to rethink rural revolution. Mao Zedong was at the forefront of this trend, conducting extensive research into village life. Mao’s studies revealed much about rural life, but his famous 1927 ‘Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan’ owed more to fiction than fact. This document established the narrative framework of rural revolution: ideologically awakened peasants find liberation by forcibly overthrowing landlords, whose ownership of excess land made them evil men. Mao also framed possible reactions to peasant activism: anyone who opposed this righteous movement would be swept aside by the revolution. The Party always presented rural revolution as fundamentally good. There was little denying that during land reform and other rural campaigns many villagers were beaten or killed, but according to Mao’s narrative, any violence that occurred was largely the result of the feudal past. Peasants needed to vent their pent up anger over generation after generation of exploitation; landlords and other class enemies, meanwhile, were said to carry out counterrevolutionary plots that also led to violence and death.

NL: Land Wars utilises a unique narrative structure to investigate rural revolution. Can you discuss this approach and the connections between narrative and history?

BD: The structure of the book grew out of my experience researching and teaching land reform over the last decade. Reading accounts of land reform, I was struck by the standardisation of the work team experience over the long course of agrarian revolution. During the course of land reform, the Party went from fighting for their lives in the Civil War to state building during the first years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Yet the process of land reform remained remarkably consistent, always faithful to the narrative first presented in Mao’s Hunan Report. In the classroom, meanwhile, I found that my students were most interested in how land reform functioned in practice. Turning my classroom into a hypothetical hamlet and dividing students into work team members, peasants, and landlords has proven highly effective for explaining the stakes of the revolution.

My goal in Land Wars is to capture the Maoist narrative of rural revolution, while also exploring how the campaign continually shifted as the Communists defeated the Nationalists and established an ever-stronger grip on local societies. The first chapter discusses the formation of work teams, largely staffed by urban intellectuals. The Party instructed these teams to bring an established revolutionary script to life. Subsequent chapters look at how work teams organised the poorest villagers to ‘speak bitterness’ about their difficult lives, a process that helped work teams place villagers into Maoist classes. In the chapters of Land Wars, as was the case in Mao’s blueprint of rural revolution, everything leads to fierce class struggle, which in turn leads to peasant liberation.

Peasant liberation was not just a literary device. Many peasants benefited from land reform, and the promise of liberation rallied many concerned Chinese citizens to the Communist cause. But in my research I found cleavages between Maoist narrative and the historical record. The story of agrarian revolution hinged on the plot device of fierce class struggle. Any mention of ‘peaceful’ land reform was roundly criticised: only the public venting of class hatred could awaken the peasant masses. Because class struggle demanded class enemies, work teams had to produce landlords and rich peasants in every Chinese village. Because many villages lacked a true exploiting class, peasants could find themselves mistakenly and illegally cast as class enemies. The centrality of struggle encouraged widespread violence that all too often was abused by local cadres in pursuit of wealth and power. And the idea that land reform would bring about liberation was belied by the simple fact that, in many places, there was simply not enough land to go around.

NL: The book’s narrative structure grows out of three classic literary texts that depict the land reform in very different ways. Why did you choose these works to frame your presentation of the Chinese agrarian revolution?

BD: The intersections of narrative and history have long fascinated me, and the Party’s framing of China’s agrarian revolution convinced me that Land Wars was a perfect chance to weave together the literary and the archival. Choosing narrative texts to inform the structure of the book, however, was immensely challenging.

Much ink has been spilled on rural revolution. From the Communist perspective, many ‘red classics’ depict land reform, including Red Leaf River, one of my favourite operas to emerge from the Civil War years. I ultimately chose Ding Ling’s The Sun Shines over the Sanggan River because I find her treatment of rural classes to be particularly nuanced. For example, her depiction of Heini, a landlord daughter, highlights the tensions between class and family. For the anti-Communist perspective, I naturally turned to Zhang Ailing. Zhang, known in the West as Eileen Chang, penned Love in Redland, a largely forgotten novel that includes a highly critical account of the process of land reform. This book, which follows an outline penned by Americans working for the United States Information Service, the precursor to the CIA, is also a product of Cold War ideology, helping balance Ding Ling’s own ideological bent.

I suspect my decision to include William Hinton’s Fanshen alongside these two novels will raise a few eyebrows. One of the most important books ever written about rural China, Fanshen is a gripping read, but it is no novel. Hinton described his opus as a ‘documentary’ of rural revolution, based on his first-hand observations. Over the years, however, I have increasingly noted the connections between Fanshen and the Party’s own framing of rural revolution. Hinton accepted Mao’s rural class scheme, even believing the worst about those who owned larger plots of land. And while he never shied away from documenting the violent excesses of land reform, he saw this as a minor problem in the pursuit of fanshen: the total liberation of China’s peasant masses.

My hope is that we will continue to read and assign Fanshen in the teaching of contemporary Chinese history. It is the book that cemented my own interest in rural revolution—it is still a great read and has much to teach future generations of students at the graduate and undergraduate levels. But we must continually rethink the text by considering how it functions as a work of propaganda.

NL: You talk about how Mao’s conceptions of class were uneasily mapped onto the countryside. Do you think the agrarian revolution actually led to a fundamental and emancipatory transformation of rural life in China? What legacies has the Maoist land reform left us with today?

BD: It is impossible to overstate the importance of agrarian revolution to the course of modern Chinese history. Mao and his comrades came to power through a rural strategy, redistributing property to win over land-hungry farmers. After winning the Civil War, massive rounds of land reform cemented the establishment of the PRC. And because the liberation of the peasant masses remains important to the Party’s legitimacy, the Communists resist attempts to examine the dark side of these rural campaigns. A true accounting of land reform must begin by linking the campaigns to the Maoist class system that left Chinese villages bitterly divided throughout the revolutionary era. Long after collectivisation erased nearly all markers of social differentiation in the countryside, Mao’s class system endured.

A few years back, I met with an elderly man who was eager to talk all things land reform with me. Then living in Beijing, he had been brought up in the countryside and had strong opinions about the Party’s various campaigns. A young boy during land reform, he had only one memory of the campaign: a popular rumour that a local landlord, condemned to death, defiantly feasted on lard before his execution. A fascinating rumour, but for my confidant in Beijing far more important had been the arrival of Maoist classes. He had been classed as a poor peasant but one of his good friends was declared a rich peasant’s son. This distinction had a profound impact on the course of their lives. He attended college, served in the People’s Liberation Army, and was now living the good life with his second wife. His friend had long ago died in their home village, never having the opportunity to improve his lot.

Like all things in China, the legacy of land reform resists easy characterisation, but the violence of these years and the stubborn persistence of the Maoist class system have shaped the course of the PRC. The violence of agrarian revolution, which the Party blamed on the forces of feudalism and counterrevolution, left scars on work team members and villagers alike. And the fates of generations of villagers were shaped by the class decisions made in a few short weeks during land reform. Land Wars is the first book on the entirety of China’s land reform campaigns, but there is much more research to be done.